So much has been written about the American health care system in recent years — in short, that it’s an insanely byzantine, profit-driven train wreck — that it’s hardly worth recounting the various and often contradictory reform proposals that have been floated to set it right. The technical debacles and, evidently, last-minute successes associated with Obamacare’s HealthCare.gov website only highlights how complex any solutions are likely to be.

In the midst of the debate, one striking image is often invoked — that of the indefatigable “country doctor” who, in some vaguely perceived, misty past, made his (almost always emphatically his, and not her) way through all sorts of weather, at all times of day and night, to patients old and young, dispensing cures and rough-hewn wisdom learned in a lifetime of caregiving.

That such a figure now belongs, almost exclusively, to our shared national memory — whether or not any of us actually ever met such a character is almost beside the point — says a great deal about our desire, and our need, for such a presence in our lives. The myth of the kindly, discreet, all-knowing general practitioner who made house calls, knew all of his patients’ medical histories and, in many cases, brought those patients into the world, endures because, deep down, we sense that that is what we require. Or, rather, that is what we all want, and it’s no less than we deserve.

[MORE: See all of TIME.com’s health coverage.]

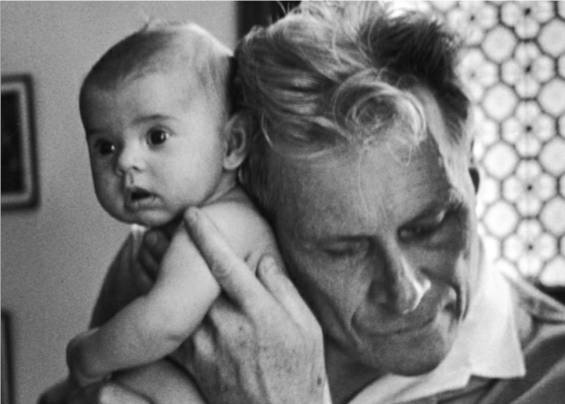

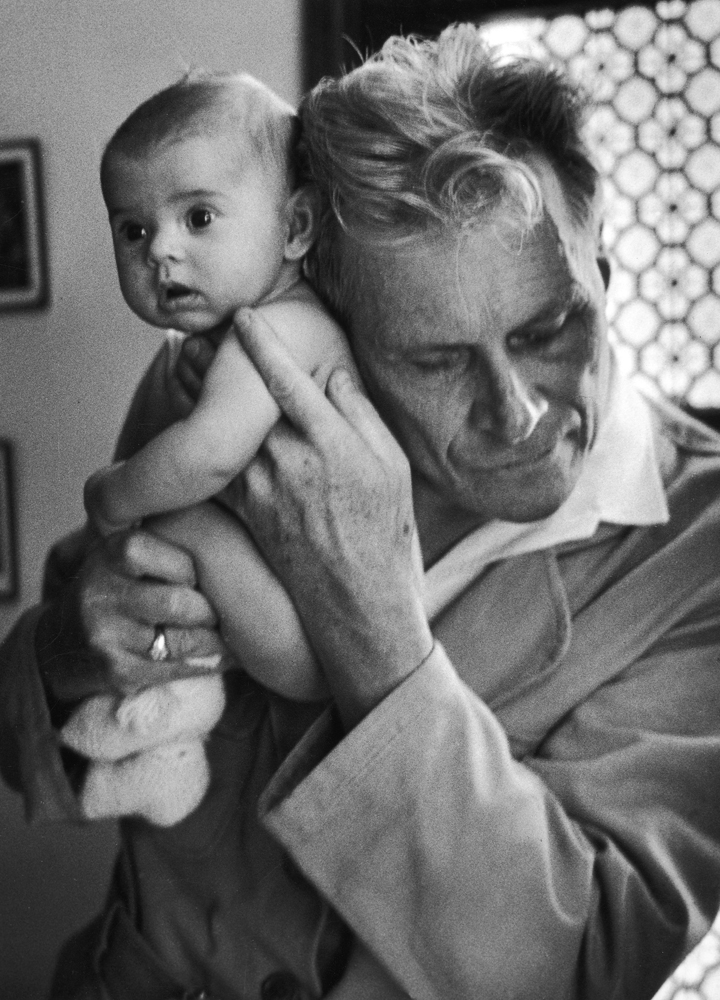

The photograph above is not, in fact, of an American doctor, but there is something about the picture that so perfectly suggests quiet, unhurried, hands-on care that it’s hard to believe, seeing it six decades later, that it’s not somehow staged. This, the picture seems to say, is how medicine is meant to be practiced: personally, with someone we’ve known and trusted all our lives.

The photo appeared in a March 1953 issue of LIFE, in a story about a French doctor who, although blind, maintained his practice for decades with the help of his wife, some nurses and, above all, the abiding trust of his patients. As LIFE wrote:

In 1931, after having served as a doctor for ten years in the village of Chelles, outside Paris, Albert-André Nast became blind and resigned himself to giving up his practice. But a patient came in for treatment and Dr. Nast found that even without eyesight he was able to diagnose the case. He decided not to quit. For 22 years [with help from nurses, his wife, Manon, and others] he has maintained the demanding routine of a country doctor, and the people of Chelles have never stopped trusting him.

Although he is a general practitioner, his first love is “Le Nativité,” the combined clinic and maternity home he created from a hunting lodge where he and his staff have delivered 4,000 babies.

There’s always a very real risk, of course, of romanticizing the past — especially when that past is so bloody, disease-ridden and generally awful as it was for so many across so much of the globe. In countless ways, modern medicine is superior — and often less invasive and painful — than the treatments our parents and their parents knew. Still, many of us pine for those days when a kindly doc would show up with little more than his trusty, battered black bag, listen to our heart and lungs, ask a few questions, and make everything all right.

And if, for most of the planet and for most of human history, those days and that doctor never existed? Well . . . more’s the pity.

— Ben Cosgrove is the Editor of LIFE.com

[MORE: See W. Eugene Smith’s Landmark Photo Essay, “Country Doctor”]

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com