On anyone’s list of the 20th century’s greatest writers never to win the Nobel Prize in Literature, Vladimir Vladimirovich Nabokov will likely appear at, or very near, the top. Of course, one can point to any number of literary masters — Graham Greene, Borges, Ibsen and others — who were, inexplicably, passed over for the honor. But the exclusion of Nabokov is especially strange — and, for his countless admirers, especially vexing — in light of the sustained excellence of the novels (those written in Russian as well as in English), stories, poems and nonfiction that he produced across five full decades.

The scope of his influence, meanwhile, can hardly be overstated. Jhumpa Lahiri, Jeffrey Eugenides, Don DeLillo, Salman Rushdie, Michael Chabon, Thomas Pynchon — the roster of prominent (and even a few genuinely great) writers whose work echoes or pays direct tribute to Nabokov’s genius is as long as it is varied.

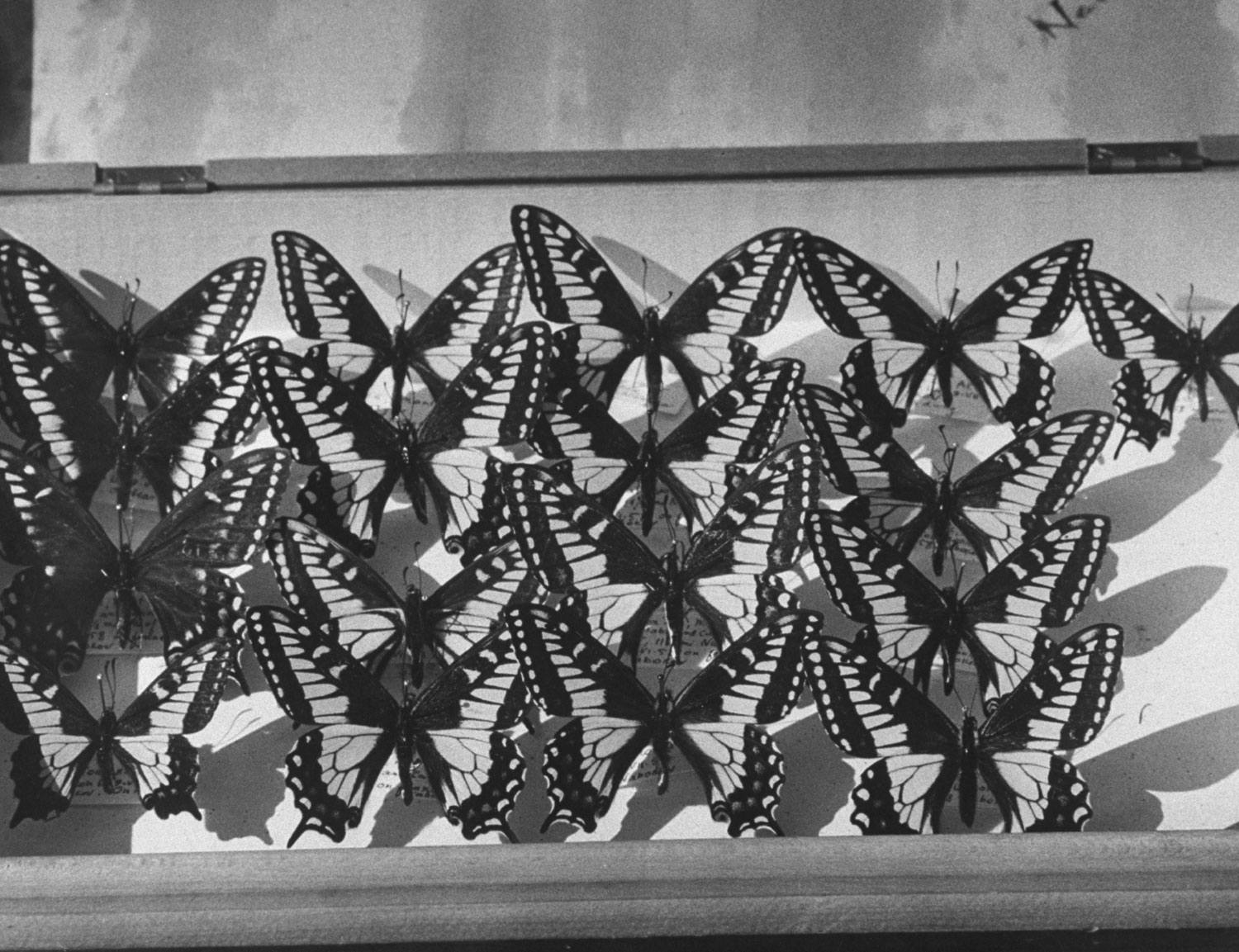

But another passion long battled with his love of writing for preeminence in Nabokov’s life: namely, the study and collection of butterflies.

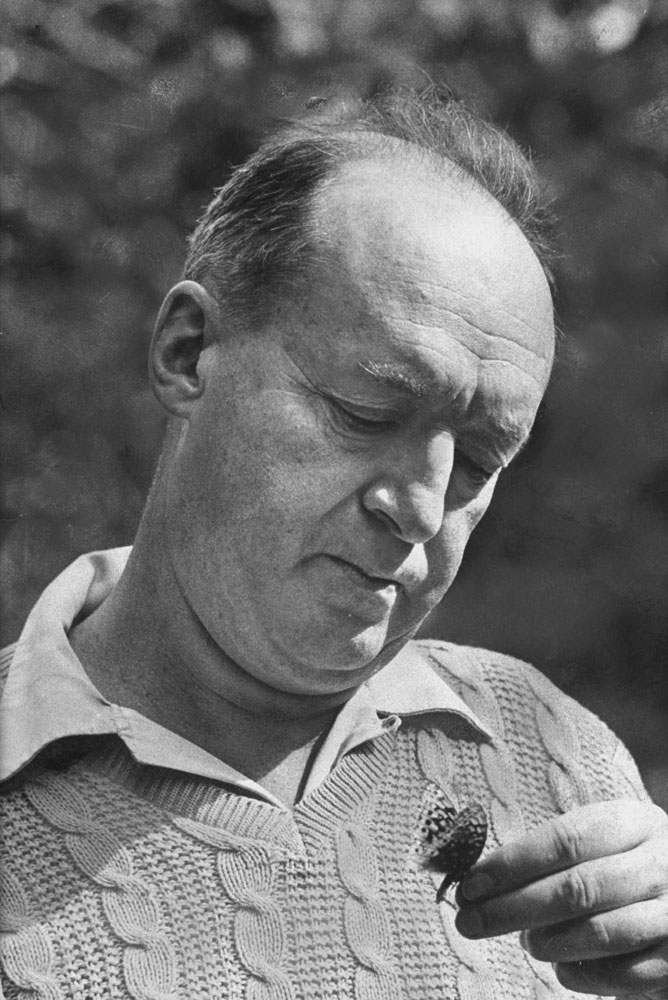

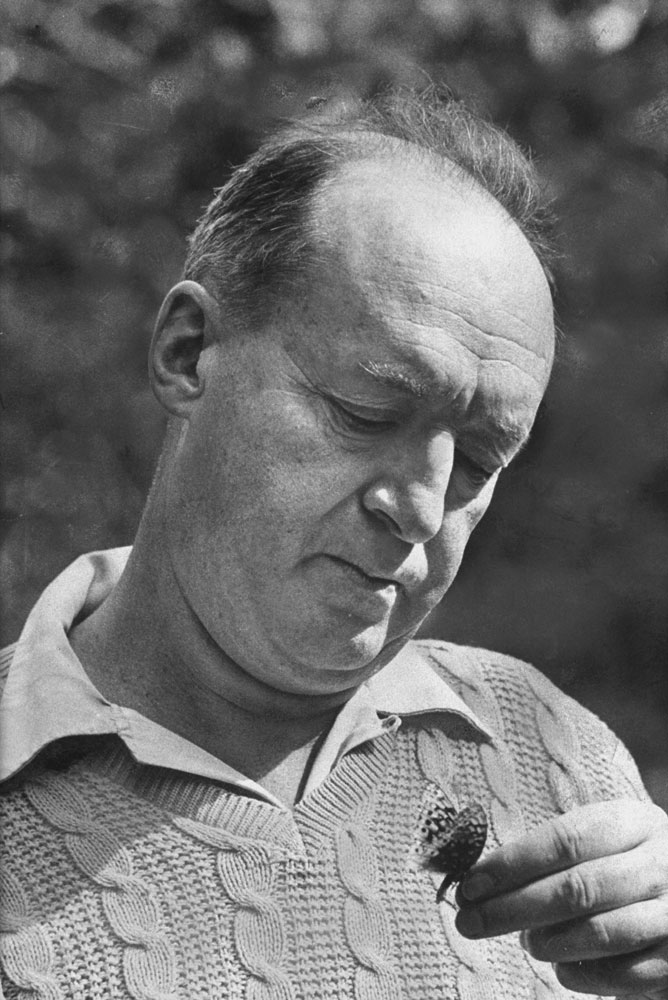

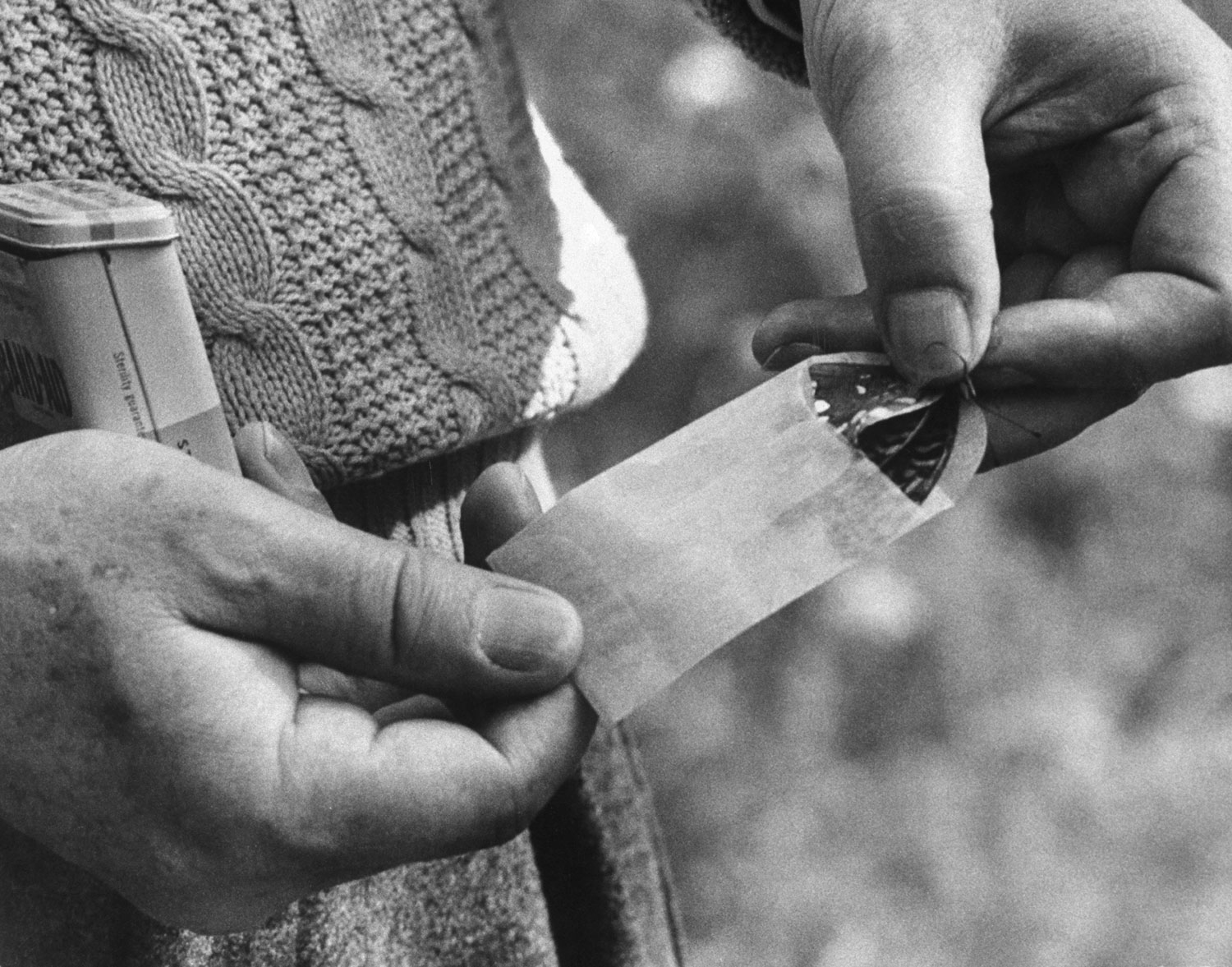

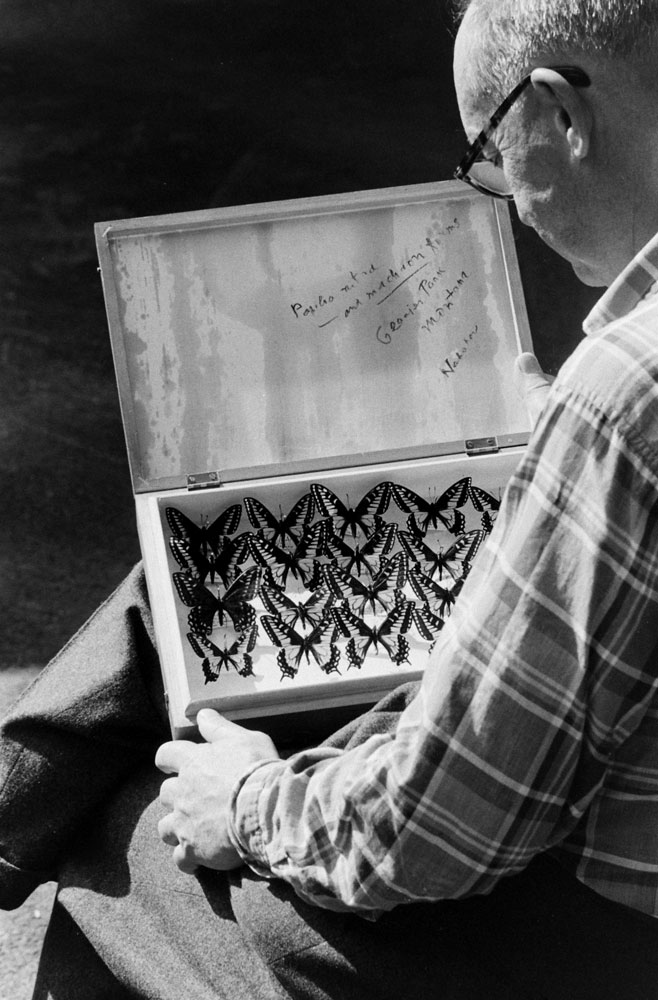

In a November 1964 article titled “The Master of Versatility,” LIFE took pains to remind its readers that Nabokov — by that time an internationally celebrated novelist, translator and teacher — was “much more than a many-tongued writer: Lepidoptera are butterflies and moths, and Nabokov is one of the world’s authorities on them.”

Here, LIFE.com presents a series of pictures — made in and around Ithaca, N.Y., in 1958 by LIFE’s Carl Mydans — that illustrate the man’s obsession with the colorful flying insects.

Born in Russia in 1899, Nabokov fled the Revolution at 17, studied at Cambridge, and went on to teach literature in the United States. (He became a naturalized American citizen in 1945.) In 1964, he was living in Montreux, Switzerland — “writing,” LIFE noted in the 1964 article, “chasing butterflies and making brilliant conversation.”

Here, in exactly the sort of sharp, amusing and cheerfully acerbic language one might expect from the author of Lolita, Pnin, Pale Fire and Bend Sinister, are just some of the remarks on life, art and, of course, butterflies that Nabokov shared with LIFE’s Jane Howard:

Writing has always been for me a blend of dejection and high spirits, a torture and a pastime — but I never expected it to be a source of income. I have often dreamed of a long and exciting career as a curator of Lepidoptera in a great museum.

One of the greatest pieces of charlatanic and satanic nonsense imposed on a gullible public is the Freudian interpretation of dreams…. I can not conceive how anybody in his right mind should go to a psychoanalyst, but of course if one’s mind is deranged on might try anything: after all, quacks and cranks, shamans and holy men, kings and hypnotists have cured people.

It is odd, and probably my fault, that no people seem to name their daughters Lolita anymore. I have heard of young female poodles being given that name since 1956, but no human beings.

I don’t think I shall ever go back [to Russia]. When I feel like returning to Russia, I go up to the mountains in pursuit of butterflies, and find just before the timberline a region that corresponds to the Russia of my youth.

I am indifferent to sculpture, architecture and music. When I go to a concert all that matters to me is the reflection of the hands of the pianist in the lacquer of the instrument. My mind wanders and fastens on trivia as whether I’ll have something good to read before I go to bed. Knowing you’ll have something good to read before bed is among the most pleasurable of sensations.

One final note, this time on the pronunciation of Nabokov’s name. In a 1965 interview, Nabokov himself said: “Frenchmen of course say ‘Na-bo-koff‘ with the accent on the last syllable. Englishmen say ‘Na-bokov,’ accent on the first, and Italians say Na-bo-kov, accent in the middle, as Russians do … [with] a heavy open ‘o’ as in ‘Knickerbocker.’ The awful ‘Na-bah-kov’ is a despicable gutterism…. Incidentally, the first name is pronounced Vladeemer — rhyming with ‘redeemer.'”

There. Aren’t you glad we cleared that up?

Liz Ronk, who edited this gallery, is the Photo Editor for LIFE.com. Follow her on Twitter @lizabethronk.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com