It’s sometimes easy to forget one particular, elemental truth: We live in a physical world.

In a digital age — when so so much of what we see, hear and act upon is comprised wholly of incorporeal ones and zeroes — the physical world can sometimes seem insubstantial. The games, apps, videos, news articles, photographs and other media we use and “consume” each day might be produced by live human beings occupying real space — but much of what we consider genuine and urgent does not, in some very fundamental ways, actually exist.

If you’re reading this on a handheld or a monitor, the letters that you’re reading right now and the words that make up the sentence that’s conveying this thought are perhaps more accurately conceived of as impulses, or bits of energy, rather than as things.

Old photographs that have been scanned and digitized, meanwhile, occupy a complex place in any discussion of what’s “real.” Obviously, a print, a strip of negatives or a contact sheet that one can hold in one’s hands are objects that have a place in the world. They occupy space. And because a roll of film developed in, say, the mid-1940s had a physical presence, it would also be heir to the perils that all other tangible objects, living and inanimate, happen to share: damage, corrosion, decay, dissolution.

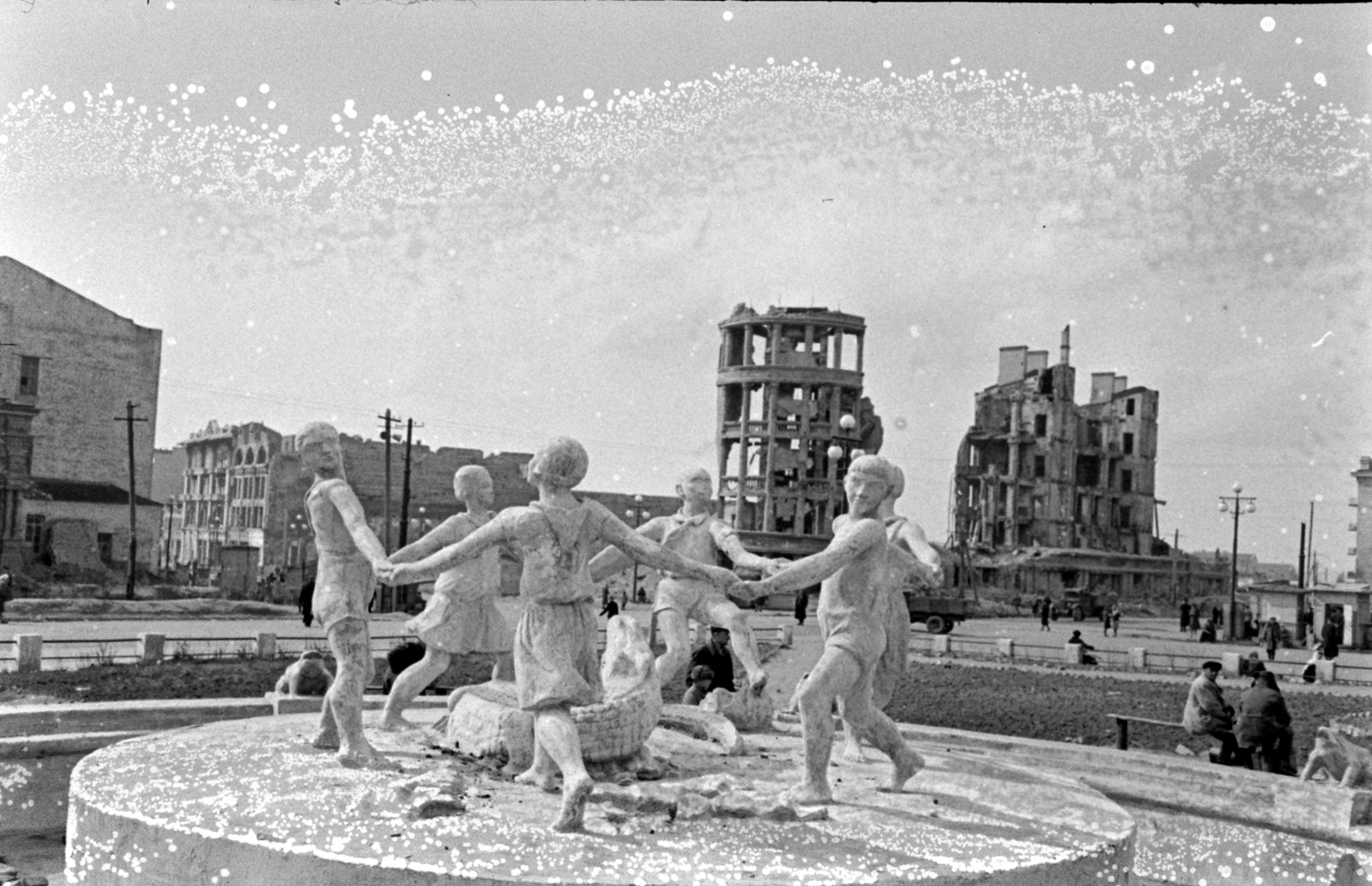

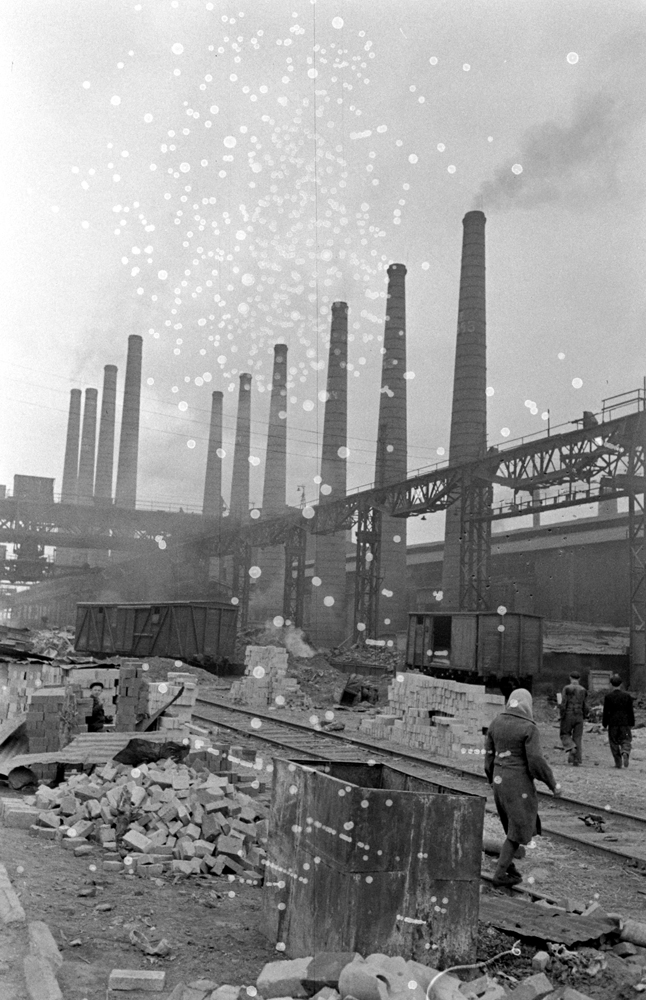

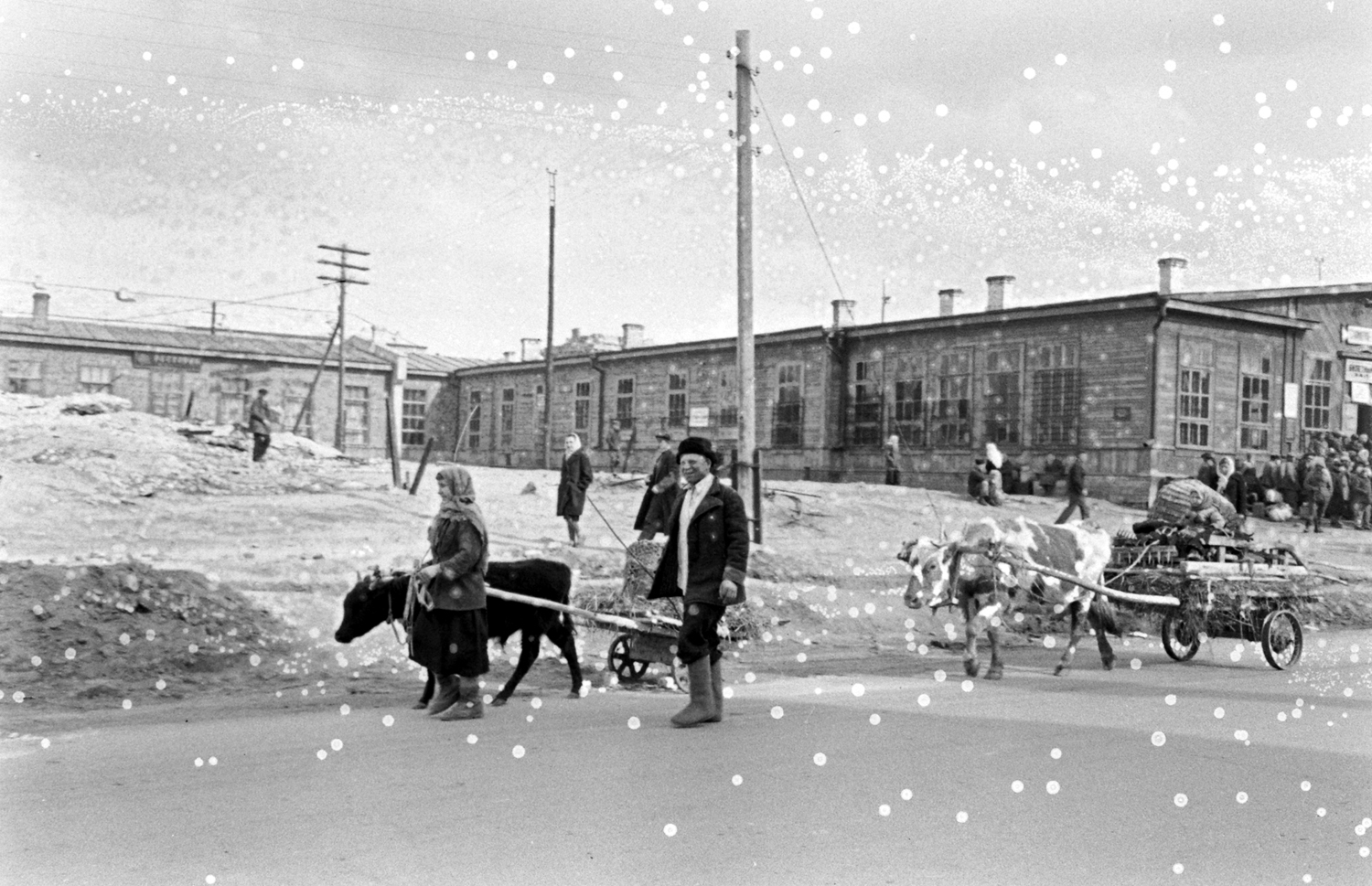

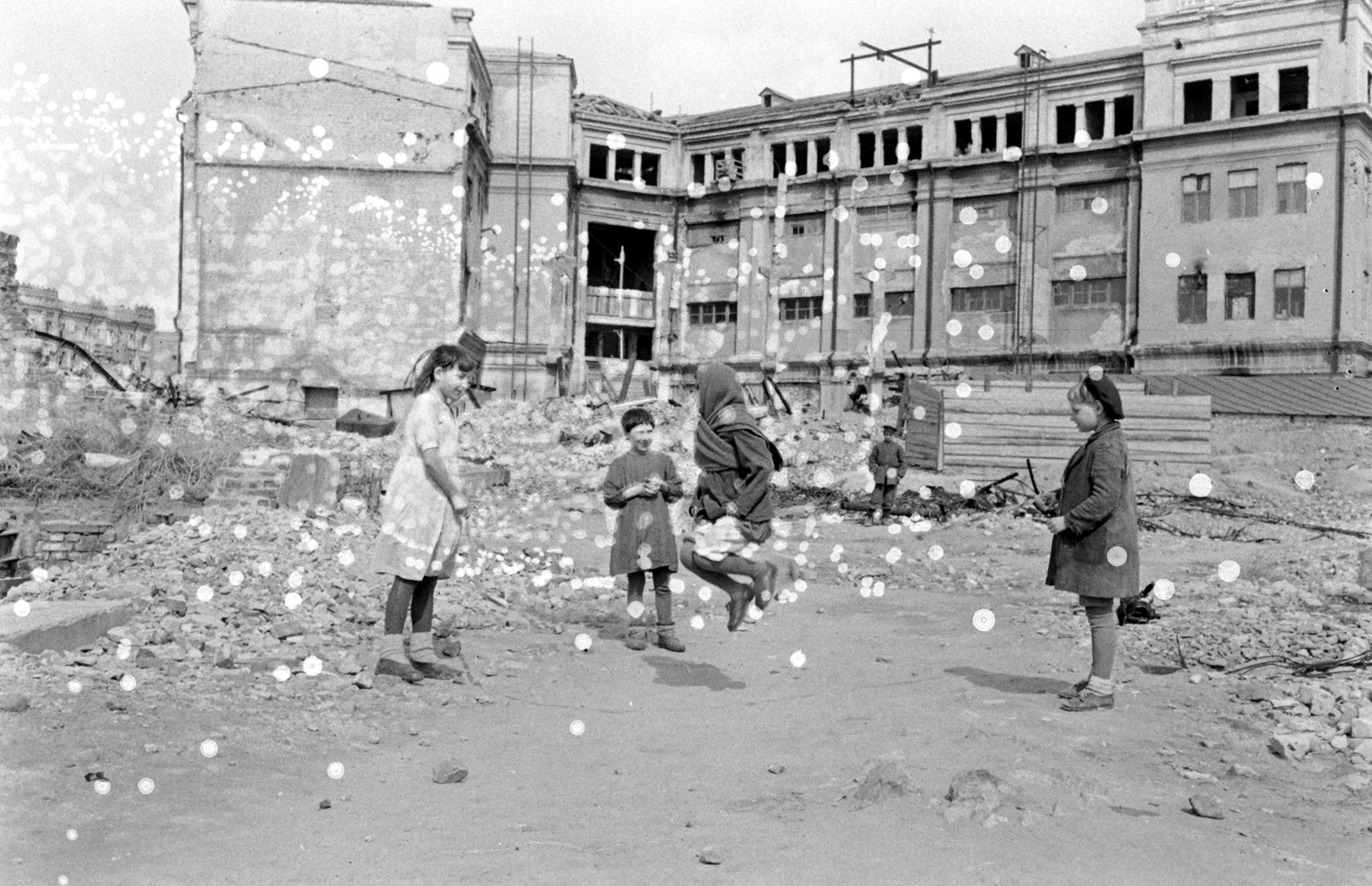

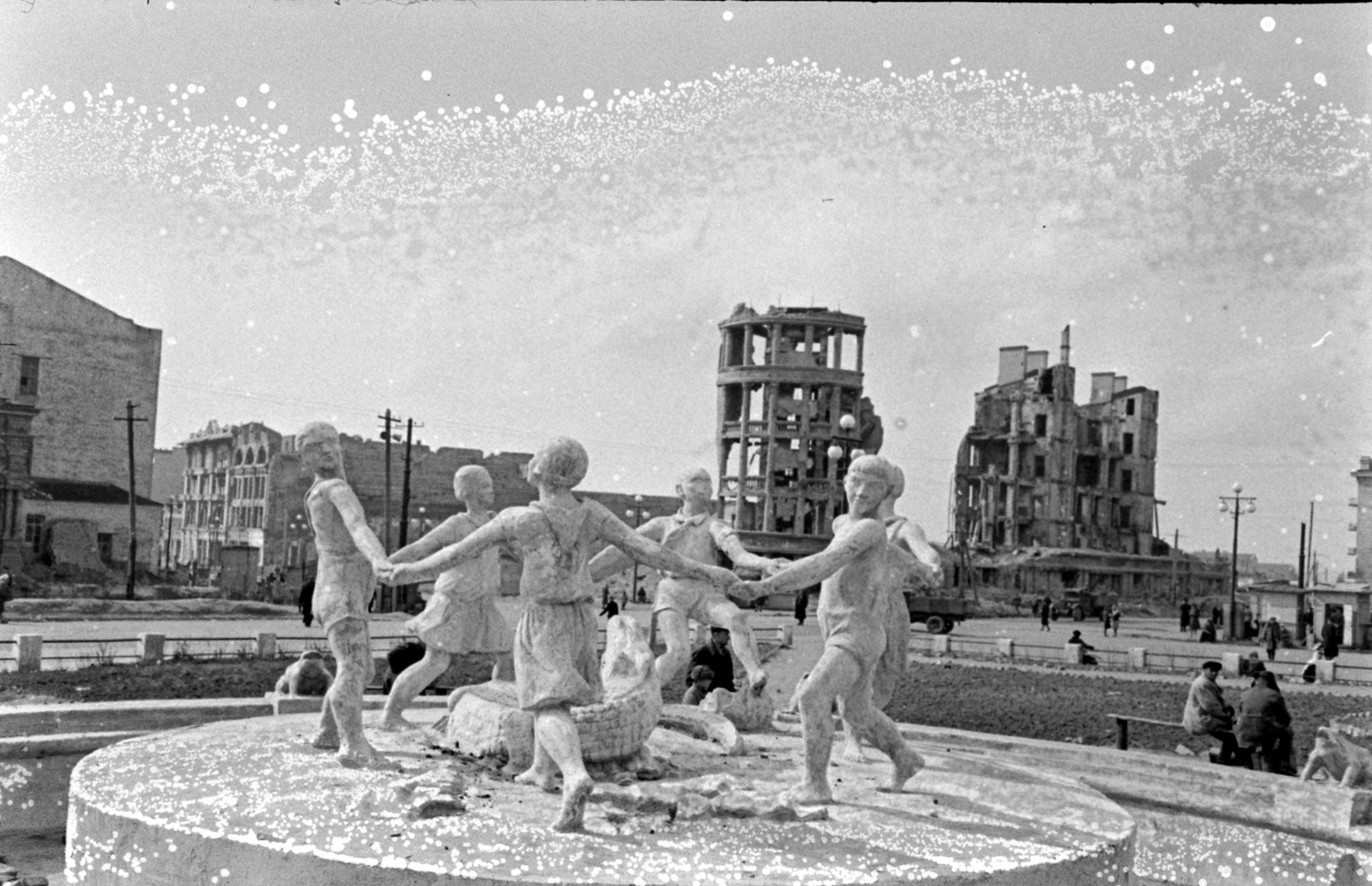

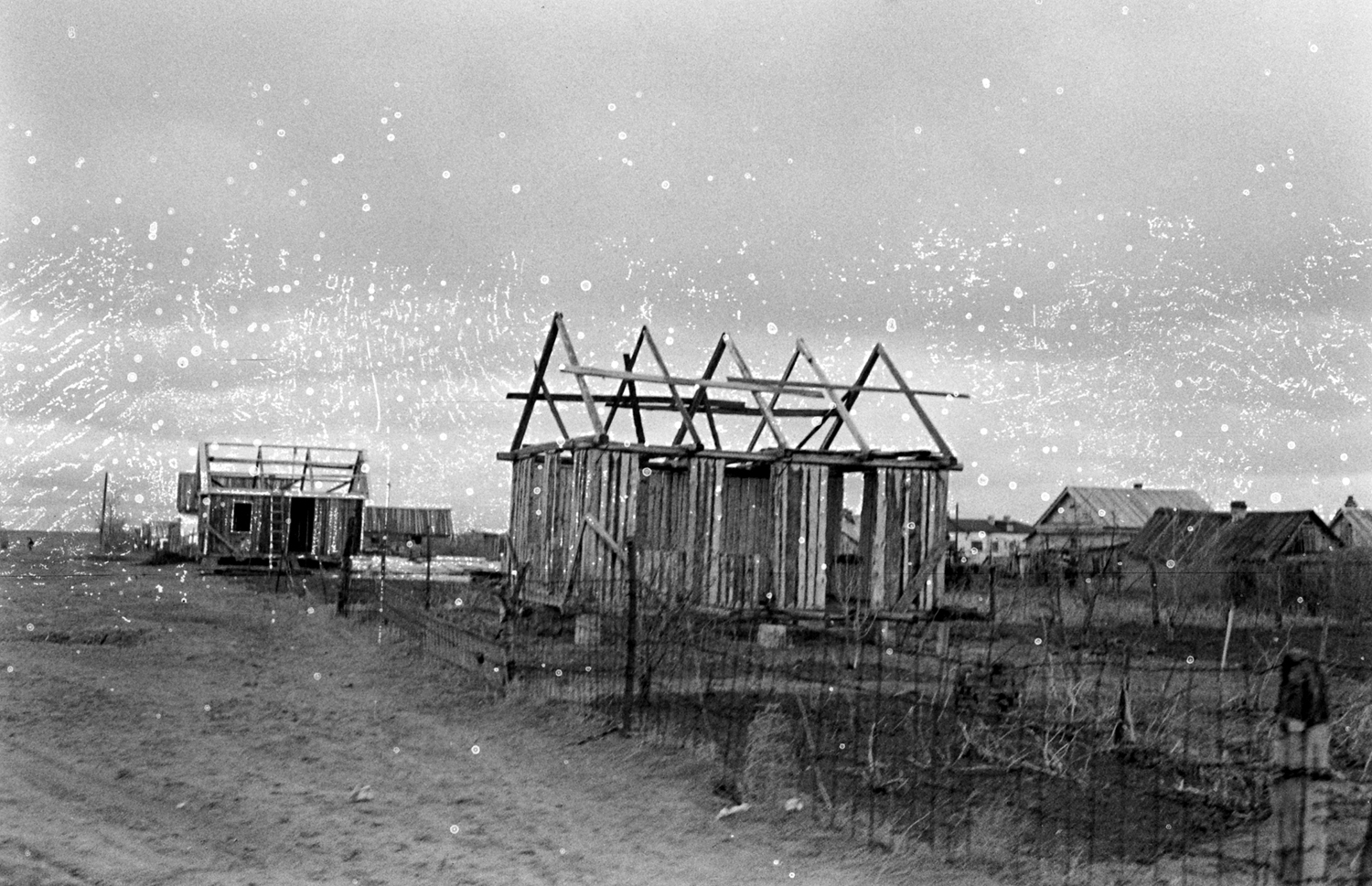

Consider the images in this gallery — photographs made by LIFE’s Thomas D. McAvoy in Stalingrad in 1947. Strong, accurate representations of a city struggling to rebuild and to regain some sense of normality after suffering unspeakable destruction during the Second World War, the images are, in fact, far removed from the film that McAvoy must have pulled from his camera after shooting the roll (or rather, the photos from many rolls) depicted here.

But it is the damage to the images — the spots created, perhaps, by mold eating away at the film’s emulsion — that not only gives many of these pictures an eerie, discordant beauty, but provides yet another way to consider the nexus of the real and what we might call the seemingly real.

The scenes that McAvoy captured, after all, did happen. Stalingrad was reduced to rubble. Years after war’s end, the only things one could find in abundance there were hunger, cold and a rough pride in their Pyrrhic victory over the Reich. And then, by some accident or mischance or plain old human ineptitude, McAvoy’s physical, photographic record of Stalingrad in 1947 suffered damage itself. The images were, in turn, transformed into near-abstract, ghostly works, within which one can still see remnants of the robust photojournalism that McAvoy consciously, intentionally created.

Finally, to add one last layer of serendipity and happenstance to the entire story, it’s worth noting that this gallery of randomly, naturally altered postwar pictures was not, strictly speaking, planned. It is curated, and the images that appear here were carefully chosen for what they could usefully say, or show — but it did not spring, fully formed, from someone’s brow. No one at LIFE.com blurted out, Hey, I have an idea. Let’s find a collection of mold-mottled photographs, and use them to discuss the fluid nature of reality, the vagaries of memory and the unique power of black and white photography to evoke the past and provide context to the present.

It would be cool if that was the case. But it’s not.

Instead, the creation of the gallery was at-once more workmanlike, and more wholly imaginative than that. We were looking for pictures to commemorate the 70th anniversary of the start of the cataclysmic and pivotal Battle of Stalingrad (August 23, 1942); came across McAvoy’s photos from two years after the war; and as we looked through mold-pocked image after mold-pocked image, gradually hit on the notion of a gallery devoted to pictures that might otherwise never again see the light of day precisely because they’re so glaringly imperfect.

We live in a physical world. This gallery’s insubstantial, digital remnants of one photographer’s labor 65 years ago serve, in their way, as forceful reminders of that fact — no small feat for a series of incorporeal ones and zeroes.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com