History is written by winners. When a conflict ends and a truce is signed, the aims and philosophies of the vanquished — their justifications for fighting, whether they instigated the war or were simply defending themselves against an aggressor — the aims of the vanquished devolve into irrelevancies at the moment of capitulation. This is hardly an argument, however, that might makes right; anyone with even a tenuous grasp of history knows that might and right usually have little to do with one another. Instead, the old saying about history and winners is simply an acknowledgement of an ancient, if somewhat barbaric, understanding between warring nations: to the victor go the spoils, and nothing is more valuable than control of the conflict’s narrative.

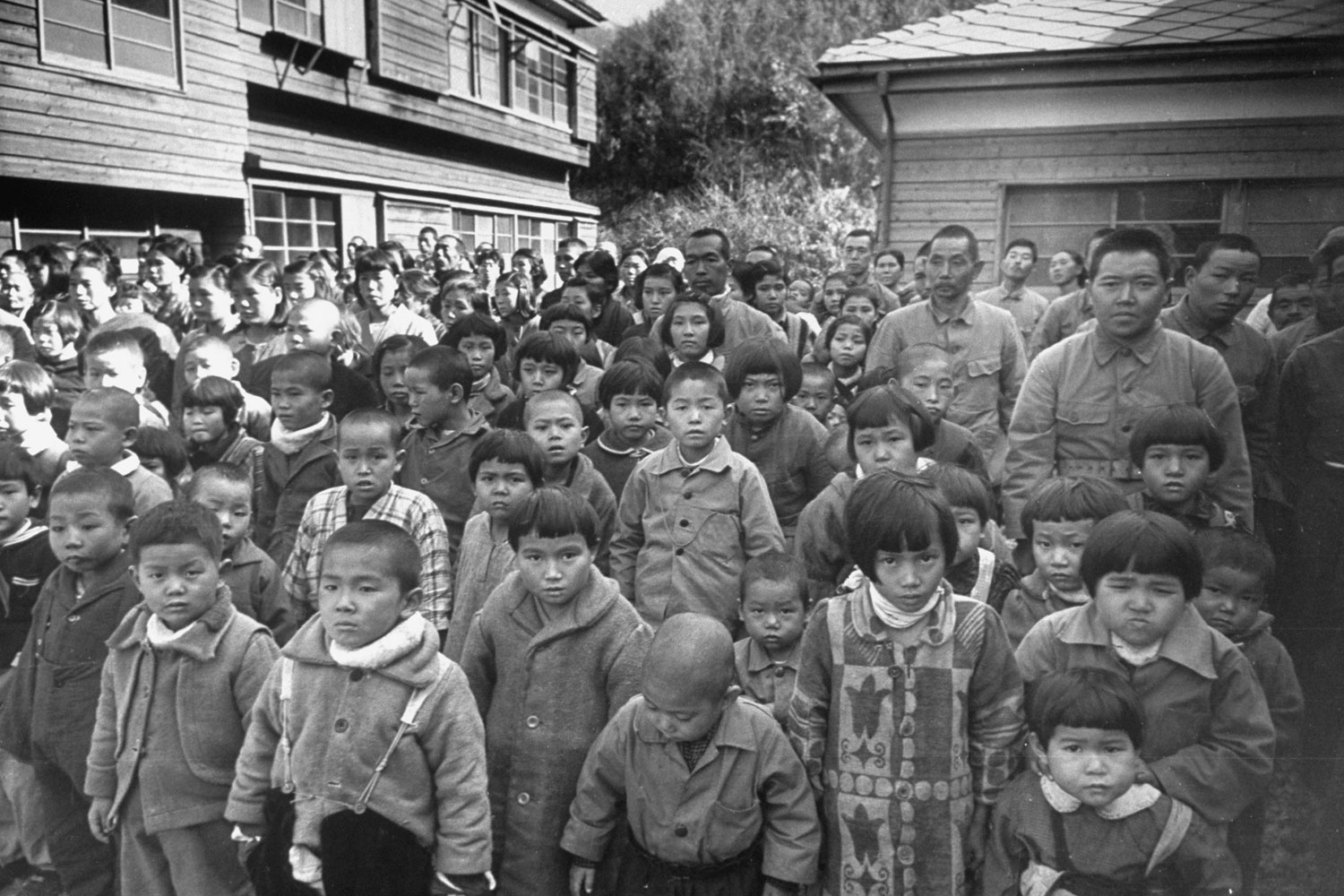

Photography, meanwhile, possesses a unique and disquieting power to distill that complex narrative — to beat the written word to the punch. The pictures in this gallery, made by LIFE’s Alfred Eisenstaedt in Japan in February 1946, offer a prime example of that disquieting power. The 1945 defeat of the Imperial Japanese Army, and by extension of Emperor Hirohito and the country’s 2,000-year-old tradition of empire, unleashed in Japan a frenzy of national soul-searching and a desperate need for explication that, in some respects, continues today. After all, by the time it was embroiled in World War II, Japan had been one of the world’s great powers for centuries. Its economy was vibrant, its military was feared, its culture and traditions were (largely) respected by people around the world. But when Japan committed to its ultimately suicidal policy of aggression and annexation in the 1930s, the country’s always simmering ultra-nationalism and its toxic notions of racial superiority had imbued its leaders and most of its people with a false sense of invincibility.

In the eyes of countless Japanese, the Empire of the Sun could never be conquered. Defeat was literally unthinkable.

Here, on the anniversary of Hirohito’s death (he died Jan. 7, 1989), LIFE.com presents these Eisenstaedt pictures as a window into a world where the unthinkable had not only become reality, but had turned the universe inside out. Hirohito — a divine being to millions of his subjects — had been transformed by defeat into a beaten (if still outwardly dignified) man.

Not a god. Not the latest manifestation in the seemingly unbroken line of deified Japanese emperors. Just a man.

The world over which Hirohito ruled in 1946 was, as these pictures attest, a realm comprised largely of ruins. The ceremonial aspects of Hirohito’s power — specifically, the multitudes bowing to him as he passes by — might remain unaffected by the cataclysm that his military adventurism brought down on his people, but the landscape of collapse and humiliation that surrounds him in these photos suggests another kind of loss, on an irreversible scale. Japan would, of course, rebound in the following decades, forging the second-largest economy in the world (behind the U.S.) by the time of Hirohito’s death. But the Japanese empire was gone; the myth of Japanese superiority — racial, military, cultural — was exploded; and the emperor was shown to be blatantly, disastrously fallible.

That Hirohito was not tried for war crimes — as so many members of his military were — remains one of the most questionable decisions made by the Allies, and specifically by Gen. Douglas MacArthur, after the war. Hirohito was, by most accounts, fully engaged in the military decisions and the culture of domination that sparked the murderous invasion of China in the 1930s and spawned the savagery that defined the acts of so many Japanese troops throughout the Second World War.

In the end, Eisenstaedt’s pictures from February 1946 remain invaluable reminders of war’s toll not because they celebrate the destruction of an enemy, but because they illustrate the cost of defeat. We don’t have to feel sorry for Hirohito; no one is less-deserving of our pity. But all these years later, perhaps we can at least consider, dispassionately, what these photographs really show us. Namely, a man and a nation undone by the oldest and most human of sins: simple, unbridled hubris.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com