After Mitt Romney’s bruising nomination fight in 2012, Republican Party officials changed the rules in an effort to streamline the 2016 primaries. But the increased influence of super PACs and an unusually deep bench of candidates mean the changes could have the opposite effect intended.

Several Republican presidential hopefuls are already preparing for a long, blistering and potentially inconclusive nominating fight that could go all the way to the national convention.

“The rules were designed to make it more of a contest so that more states and activists are engaged in the process—and that’s definitely going to happen,” says Steve Duprey, the New Hampshire National Committeeman who helped to shepherd the rules changes through in 2012 and 2013. “The bad news is, this campaign is likely to go on longer than we’ve seen in a long time.”

Republican Party officials blamed a broken primary process in 2012 for contributing to Romney’s defeat and set about changing the party rules to keep it from happening again.

The committee shortened the calendar between the first caucus and the last primary, required the binding of delegates in primaries and caucuses and raised the bar for nominating candidates on the convention floor, requiring a nominee to win the majority of eight state or territory delegations. The idea was that a compressed timetable would favor better-funded candidates, while keeping lesser candidates from making a scene in Cleveland.

But three years later, the primary will be playing out in a very different stage, one where a massive crop of candidates with huge sums of unlimited cash have little incentive to exit early. Party operatives and campaign aides are predicting a longer, more intense contest next year than in 2012. They believe it will be more akin to the Obama-Clinton fight in 2008—a slow state-by-state contest to rack up delegates—only with a lot more candidates remaining competitive.

On paper, the RNC’s efforts will shorten the time from the Iowa Caucuses to when the nominee clinches a majority of delegates—primarily accomplished by a successful effort to keep the first contests from advancing into February. But Romney’s victory was all-but-assured months before he secured 50% of convention delegates in late May 2012.

Josh Putnam, an assistant professor at Appalachian State University who runs the exhaustive Frontloading HQ blog tracking the primary calendar, explains that about 50% of delegates to the GOP convention will be awarded by March 8, 2016, with 75% awarded by April 26—both weeks earlier than in 2012. “That is important because the last two Republican nominees established a lead by that 50% point and had clinched the nomination around the time that 75% of the delegates had been allocated,” he says.

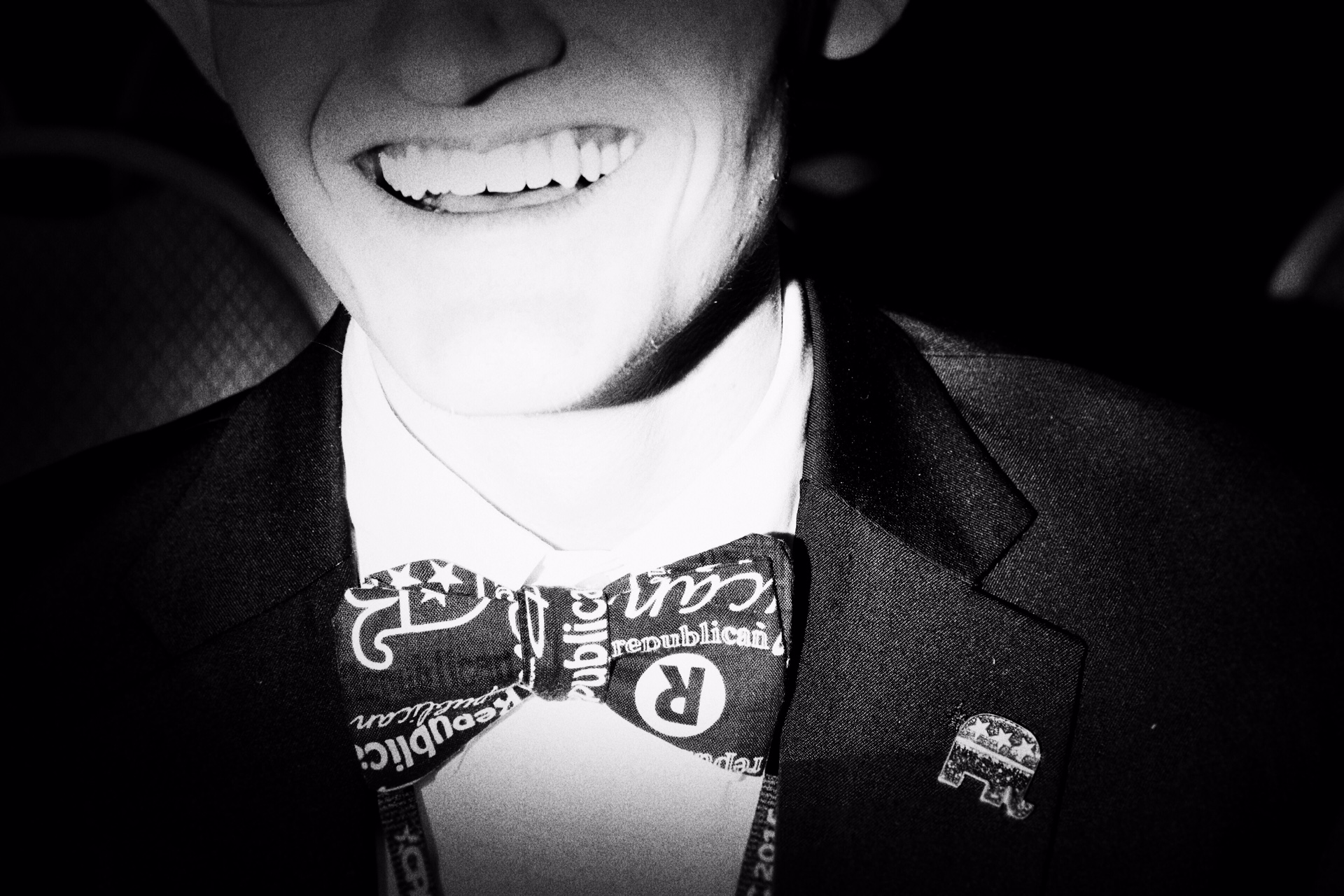

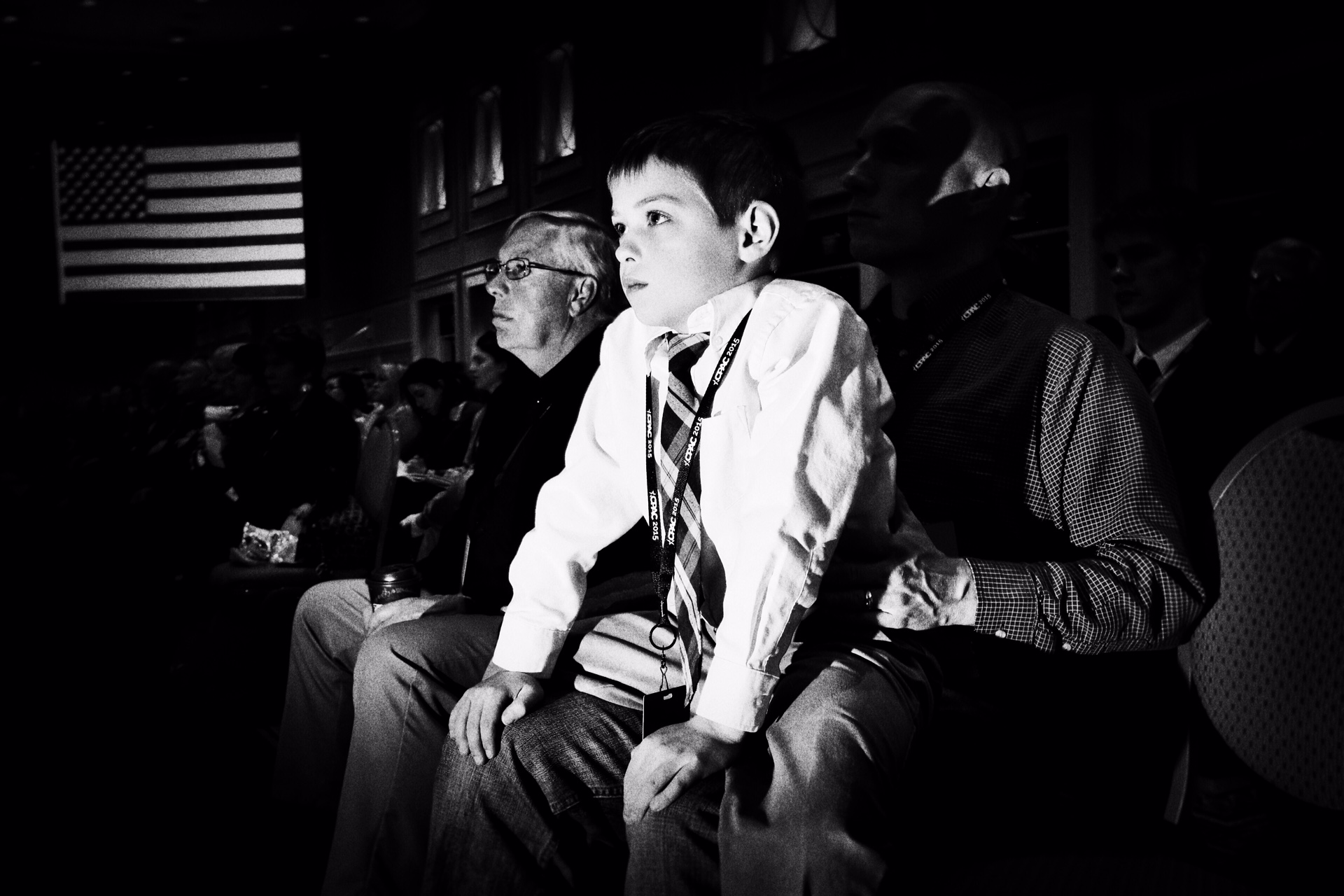

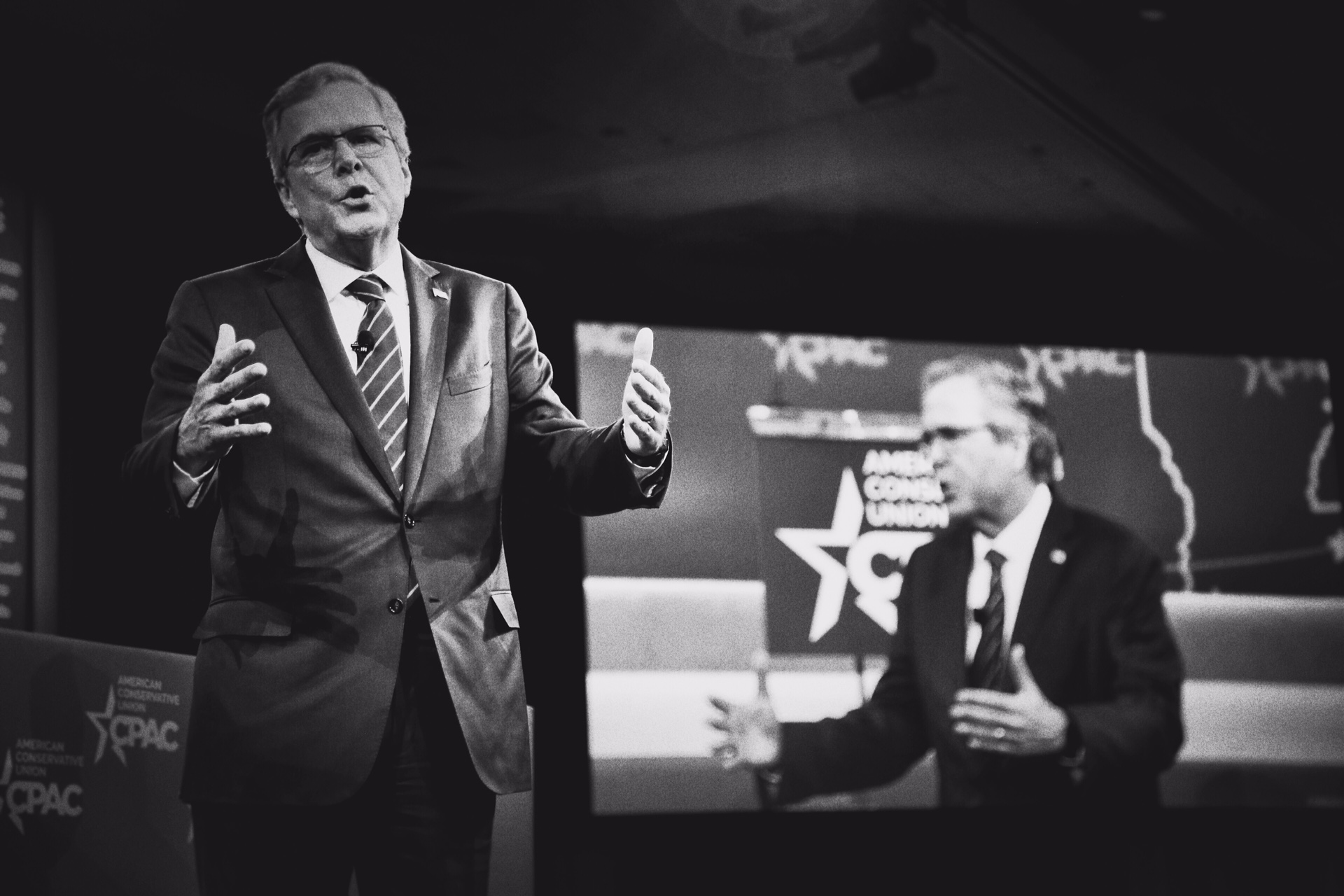

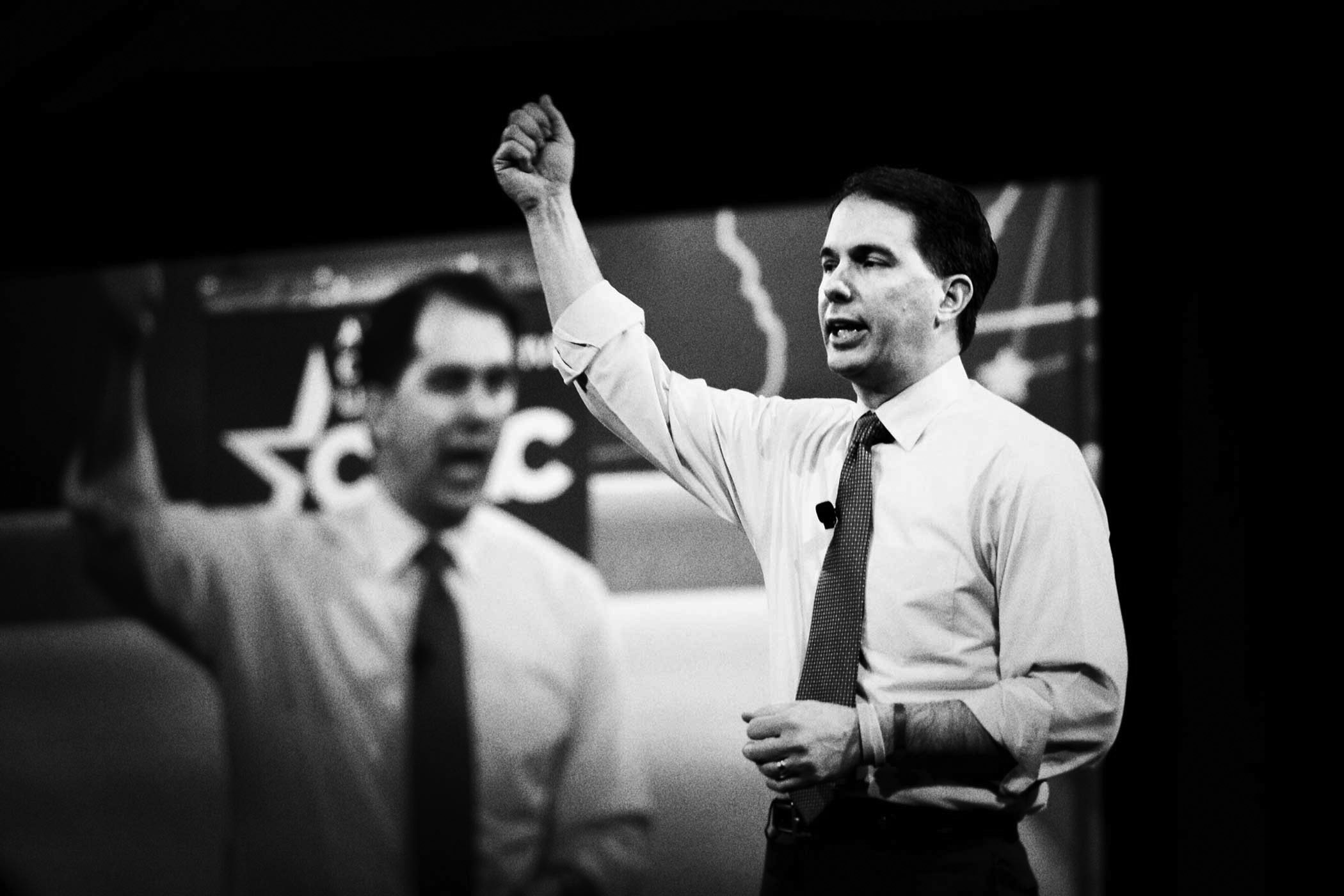

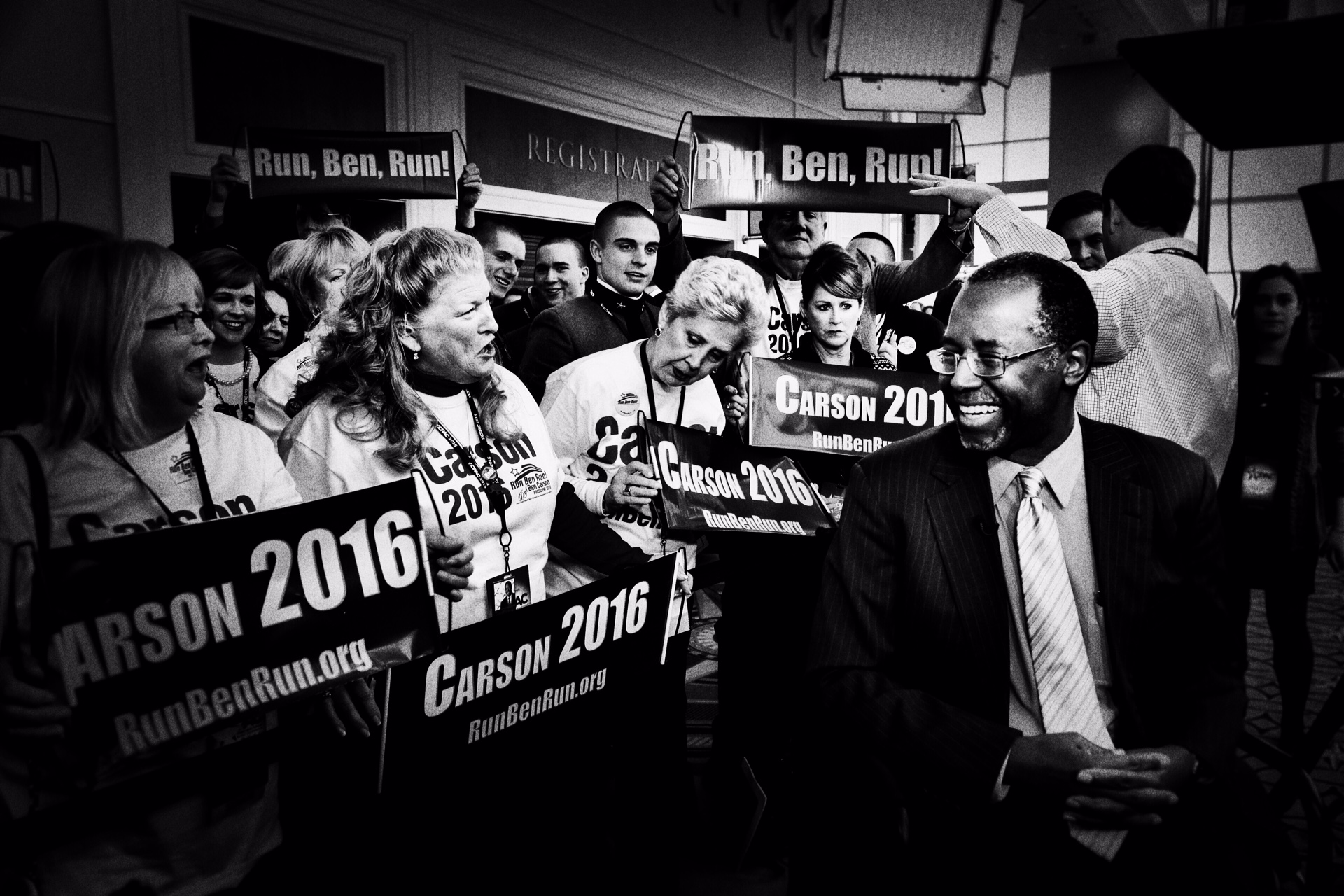

Behind the Scenes of CPAC

But changes in campaign finance and an unusually strong field threaten to throw that precedent out the window. Now many party strategists expect four to six candidates to emerge as a top tier from the four early states of Iowa, New Hampshire, Nevada, and South Carolina. With roughly the same delegate support and momentum, they expect that the proportional contests in early March—when a front-runner usually emerges—may not be decisive. On March 1, for instance, more than 600 delegates are set to be awarded. “Lots of people will be able to claim victory that day,” said one top advisor to a Republican candidate.

Meanwhile, the rest of field may be in no hurry to go anywhere. The explosion of mega-donors writing significant checks to candidates and their super PACs has mitigated the historical impetus for dropping out, while the lessons of the up-and-down 2012 primary have incentivized staying in the race even when the odds turns slim.

“This could actually be a convention that matters for the first time since 1964,” says Saul Anuzis, the Michigan state chairman for Sen. Ted Cruz’s presidential bid and a former RNC member who backed the rules changes. “I still don’t think most of the campaigns have an infrastructure in place to deal with it.”

Not all strategists blame the predictions of a messy nomination process on the new rules. Michael Shields, the former RNC chief of staff, told TIME he believes the deciding factor in stretching out the primary in 2016 is likely to be the number of candidates who can raise money. “It would have been longer without the reform,” he said.

To be sure, all the prognosticating could also be wrong—a single candidate could build enough momentum in the early states to run away with the nomination in weeks. But with a field of more than a dozen candidates that appears at the moment to be unlikely.

Some campaigns are only just coming to the realization that this contest will be far different from the last, having spent the past months focused on the early states. “Those who have started to think it through recognize it’s going to be a long chase for delegates,” said a veteran GOP strategist.

Anuzis said Cruz is planning for the long haul and is already eyeing favorable congressional districts in California—which will go to the polls on June 7, 2016, and awards its delegates to the winners in each congressional district. Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker’s campaign has hired Jon Waclawski, a veteran of the RNC counsel’s office who was involved in drafting the rules after the 2012 campaign, as its counsel and chief delegate counter. People close to former Florida Gov. Jeb Bush’s campaign said his team is drawing up plans to deal with what they expect to be a painstaking fight for delegates.

“This changes the way you have to run your entire campaign,” says one candidate aide. “You really do have to target, racking up local endorsements, for instance. Those people are going to be important when you’re competing on a congressional district by congressional district basis.”

Former Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee’s advisers see the proportional contests in early March, and the potential for a drawn out delegate fight, working to their advantage. Former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum told reporters Thursday that he is broadly supportive of the rules changes, but is worried about the compressed calendar, “and it becomes just a money issue, and not an issue of momentum.”

What remains to be seen is whether this intensified primary process will be a benefit or liability to the eventual nominee in the general election. The knockdown, drag-out 2008 Democratic contest is viewed as having ultimately helped Obama, who emerged tested with a network of support outside of the early primary states. For months after winning the nomination, Republican presumptive nominee Sen. John McCain could hardly gain notice from the media. “Will there be some broken glass, will there be some negative attacks, sure,” Shields acknowledged. “But I do believe this process, like the Obama-Hillary one, will leave our nominee stronger.”

Others are less sanguine, fearing the compressed timeframe could result in a more weakened nominee, battered by months of attacks from candidates and super PACs

“It’s pretty different when it’s a two person extended race opposed to a multi-person race—and in 2008 you didn’t have super PACs playing the role that they did and they generally tend to go negative,” said another longtime GOP operative.

With reporting by Philip Elliott/Little Rock, Ark.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com