To fans of Sherlock Holmes, the setup feels familiar: A wealthy spinster is bludgeoned to death in her Glasgow dining room one foggy night while her maid is out buying the evening newspaper. The murderer is apparently someone she knows, since there is no sign of forced entry. And burglary is insufficient as a motive, since only one piece from the victim’s massive jewelry collection is missing: a unique, crescent-shaped diamond brooch.

The police bumble the case from the beginning, latching onto the least likable suspect, a gambling-den operator with a checkered past, and sticking with him even after the key piece of evidence — a receipt showing that he’d recently pawned a diamond brooch — turns out to be a red herring. A savvy investigator intervenes to set things straight. But the investigator is not Sherlock Holmes: It’s his real-life creator, Arthur Conan Doyle. And the tale of murder and miscarriage of justice is true.

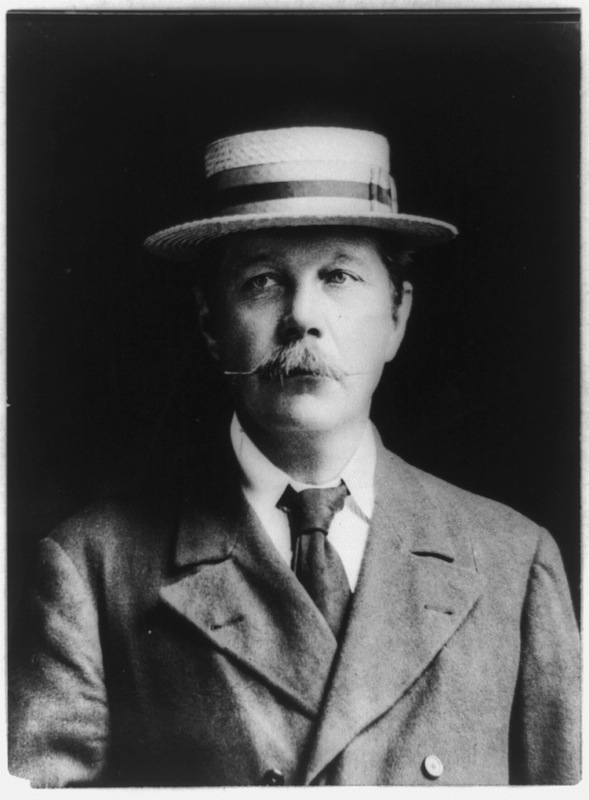

Doyle, born on this day, May 22, in 1859, might have had more in common with Dr. Watson, at least on the surface. He had been a practicing physician, like Watson, before he took up writing. It was while studying medicine at Edinburgh University, in fact, that Doyle met the man who inspired the character of Holmes: the surgeon Joseph Bell, “whose specialty was diagnosis through observation and deduction,” per TIME’s 1924 account.

But Doyle was Holmes at heart — an enemy of injustice and a stickler for solid deductive reasoning. Like Holmes, Doyle sometimes meddled in murder cases when he believed the police had veered from the right track. One of the most famous of these was the 1908 murder of 82-year-old Marion Gilchrist, the wealthy spinster, and the wrongful arrest of Oscar Slater, the gambling-den operator.

After reading news accounts of the flimsy evidence against Slater, Doyle decided to conduct his own investigation, according to Janet Pascal, the author of Arthur Conan Doyle: Beyond Baker Street. He dug up contradictory clues and discovered that an eyewitness — the maid, who had seen a man running from the crime scene as she returned with the paper — had been coerced by police into fingering Slater. Ultimately, Slater was exonerated and released from prison.

“Sir Conan Doyle, you breaker of my shackels, you lover of truth for justice sake, I thank you from the bottom of my heart,” Slater wrote to him, according to Pascal.

While Doyle might have had the heart of Holmes, however, he didn’t quite match the fictional detective’s success rate. In his autobiography, Doyle candidly reported that his powers of deduction didn’t always trump ordinary police work. On one case he’d hoped to crack, he said, the police quickly identified the culprit “while I had got no farther than that he was a left-handed man with nails in his boots,” per Pascal.

Read more about Doyle from 1924, here in the TIME archives: An Author Tells of War, Murder, Spooks, Disease

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Democrats Believe This Might Be An Abortion Election

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com