Analyzing the title sequence to Mad Men has become something of a sport for the show’s fans. Does the suited man hurtling toward earth foreshadow protagonist/anti-hero Don Draper’s literal death or his figurative demise? Does it echo the chilling photograph of a man who jumped from a burning World Trade Center tower? (Showrunner Matthew Weiner has said emphatically that it does not.) Whatever it represents, where did Imaginary Forces, the agency that produced the sequence, get the idea?

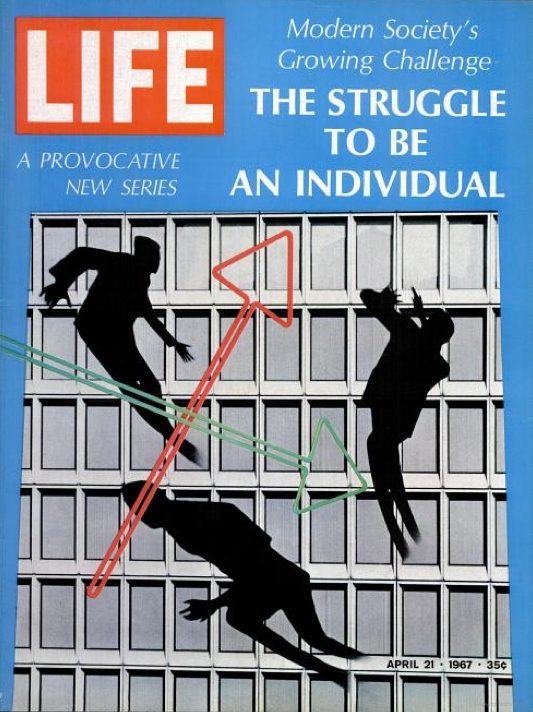

Here’s another idea: it’s now been pointed out that the design has many similarities to a 1967 LIFE Magazine cover, the first in a four-part series on “The Struggle To Be an Individual.” The cover, like Mad Men’s credits, features silhouetted men against the backdrop of a 1960s-era skyscraper. Both suggest a sense of helplessness, of ceding control to powerful forces beyond one’s self.

The Imaginary Forces team that produced the credits has spoken about some of the inspiration behind the design. Weiner initially approached them with the skeleton of an idea — a man walks into an office building, takes the elevator to the top and jumps — and they began developing storyboards. Those boards included a Volkswagen ad, movie stills and, as designer Steve Fuller told Print, “the design stew that’s been swirling around in our head over the last 15 years since we left college.”

Although a representative from AMC confirmed in an email to TIME that similarities between the LIFE cover and the title sequence are purely coincidental, the photo essay the cover advertises in many ways articulates the existential crises Draper faces in Mad Men. As an ad man, Draper sells access to an American dream he himself hasn’t entirely bought into. Even as he accumulates successes in the boardroom and the bedroom, the satisfaction never lasts longer than a few drags of a cigarette that might kill him anyway.

The ethos of the 1960s is, of course, omnipresent in Mad Men — and not just in its fastidious commitment to the furniture and fashions of the time. In post-WWII America, many Americans had settled into the comfort of corporate jobs that afforded them the same white picket fence and station wagon their neighbors boasted. Responding to that phenomenon, books like William H. Whyte’s The Organization Man, published in the mid-1950s, lamented how modern workers’ collectivist group-think ran in opposition to creativity and innovation. The sociological treatise The Lonely Crowd, which sits on the radiator in Don’s office, similarly observed that people’s yearning to understand their position as it compared to everyone else’s limited their potential for self-actualization.

The photos in “The Struggle To Be an Individual” suggest anonymity amidst this 1960s uniformity: an aerial view of an endless expressway, looping seemingly to nowhere; a housing development in which every unit looks identical; a geometry of office workers sitting row by row at the same typewriters, with the same hairstyles and the same stacks of paper.

“You can sign up for just about anything you want and it will be delivered with speed and polish,” one caption reads. “Everything you can get your hands on is worth having. The trick is in deciding what you want.” Draper, of course, can’t decide what he wants: the suburban life or the mistress in the city, the towering Manhattan skyline or the hazy skies and swimming pools of Los Angeles.

One caption, perhaps more than any other, seems to describe the journey Draper has undertaken as the series winds to a close. It accompanies the photograph of those looping Long Island expressways and dictates, almost like a meditation tape, how the driver might place himself in space and time:

Imagine yourself an astral body, streaking along, stable in the galaxy … before you know it, the unseen land will disappear behind you. Your turn will come to peel off, and home you’ll go, untouched by any weather.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com