More than two years after the death of Hugo Chávez—the fiercely loved and despised Venezuelan President, the populist with a booming voice—the country he left behind remains in disarray.

Demonstrations against his successor, Nicolás Maduro, have been fueled by anger and frustration over high inflation, violent crime and shortages of basic goods. That has led the Venezuelan people to question what El Comandante left for them.

Alejandro Cegarra, a 25-year-old photographer who grew up in a relatively privileged middle-class family, in what he called “a good area” of Caracas, the capital city of 2.9 million, is among them. In the wake of Chávez’s death, he began looking at the political, social and economic factors that pushed his country to its current point.

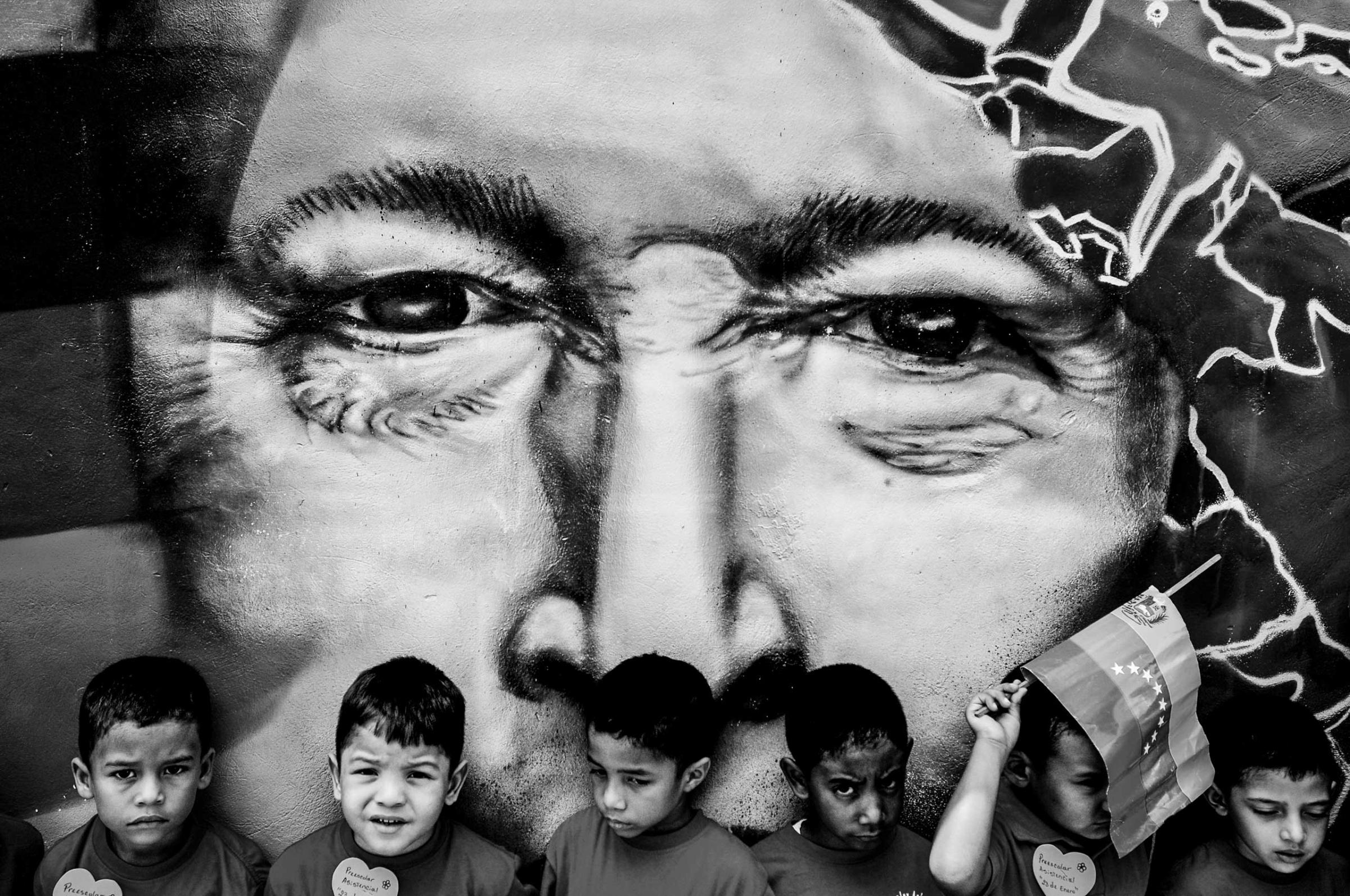

He photographed the empty shelves at markets that have come to represent the economic crisis. “You have a picture from a month ago and then one from a year ago,” Cegarra says, “but it still looks like the same style.” He came across a family being evicted by troops so a highway could be built—though months later there had been no progress—and documented the murals of Chávez around Caracas. “It’s everywhere,” he says of the late leader’s face, comparing the sightings to that of Chávez mentor Fidel Castro. “It’s worse than Cuba.”

Cegarra also turned his lens to insecurity. On Feb. 12, 2014, he found himself covering a largely peaceful demonstration against Maduro’s administration that winded down into a group of protesters who clashed with security forces, during which Bassil Da Costa, a 24-year-old university student, was fatally shot in the head.

“I remember the face of one of the guys who was carrying him,” he says. “It was panic, fear, he was crying.” Cegarra fell at some point during the mayhem, but the students around Da Costa wanted him to capture the scene, to make a record of it. One of them lifted Cegarra up and urged him to get a shot. Da Costa’s death, and that of a Maduro supporter, became a flashpoint in the unrest.

Cegarra couldn’t look at the image for a while, admitting it’s “not a picture I would show and feel especially proud,” despite it being “one of the few moments when I actually saw the power of a picture.”

The photographer also visited El Rodeo prison complex, where deadly violence broke out four years ago. “Normally I’m the target of these guys, so I went there and talked with them face to face,” he says, “trying to understand the bad choices or circumstances of why they are there.” He recalls it was a positive experience, one that enabled him to leave his prejudice at the door, to grow up a bit and understand the city around him. “The cycle of violence is hard to break in the slums, and there are too many factors.”

He went to the jail three times, and later photographed at a funeral for a gang member. “That guy was my age and I was there alive taking pictures, and he was there [in a coffin],” he says. “I have to see the other part of my country—see it, live it and say, well, I grew up in a bubble and my country is this.”

All of that gets back to why Cegarra began this project in the first place. “Venezuela is trapped between its past and future,” Cegarra says, likening the reality of the present-day to an adolescent finding its way between youth to adulthood. “It was something that … was touching me, personally,” he adds, recalling the influence of Chávez. “What his legacy was and what he left for me.”

Alejandro Cegarra is a photographer based in Caracas and featured with Getty Images Reportage. Follow him on Instagram @alecegarra. This series will be exhibited during the Visa pour l’Image festival in Perpignan, France, later this year.

Mikko Takkunen, who edited this photo essay, is an Associate Photo Editor at TIME. Follow him on Twitter @photojournalism.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com