On one hand, the announcement that Saudi Arabia’s King Salman will not attend President Obama’s Camp David summit of Gulf Arab monarchs on Thursday, despite having earlier accepted the invitation, highlights all over again the considerable strains between Washington and Riyadh. In the four months since Salman came to power, the Kingdom has defied the U.S. by starting one war in Yemen and reviving the most problematical elements in another, sending new support to the Syrian opposition forces that include the Nusra Front, an affiliate of al-Qaeda.

On the other hand, the king’s absence—ostensibly to deal with a brief cease-fire in Yemen, but widely viewed as a snub—will give U.S. officials a chance to size up the young fellow who the monarch has invested with immense new powers: His son, also known as the Minister of Defense, as well as president of the royal court. Mohammad bin Salman may be 29, as some accounts have it, or 34, the age offered in other reports. Or somewhere in between. The uncertainty speaks volumes about how little is known of the fresh-faced young prince, derided by the Supreme Leader of arch-rival Iran as “an inexperienced youngster.”

“I don’t think anybody knows who he is,” says F. Gregory Gause III, head of the international affairs department of the Texas A&M University Bush School of Government and Public Service. “He’s never had a job where he had a counterpart with Americans in bilateral talks. I think there’ll be plenty of people looking to size him up.”

The jobs that young bin Salman holds are known well enough. Defense is a ministry awash in money. “That’s where the rake-offs occur in the system,” says Charles A. Freeman, who was U.S. ambassador to Saudi Arabia during the Gulf War. And head of the royal court is basically chief of staff, putting the king’s son in daily charge of the ruling apparatus.

But the lack of information about bin Salman himself says a great deal about how fast the ground is shifting in the Middle East—and especially in the House of Saud, the family that has ruled the Kingdom since it appeared on the sands of the Arabian Peninsula in 1932. Saudi-watchers used to be the Middle East’s version of the Kremlinologists who studied the Soviet Union. The players in both places moved at processional speed and change, should it occur, was glacial. But then Salman took power following the January death of his brother Abdullah, who ruled for 10 years.

“Basically what’s happened in Saudi Arabia since the death of Abdullah is a series of political coup d’etats,” says Freeman. “In Arabia, genealogy is ideology and lineage really is faction. In any one-party system you have factions, and in a one-family system you have factions.” Despite Salman’s reputation as a conciliator between branches of the family, since ascending to the throne, Freeman says, “he’s basically cut them all out.”

Salman, 79, was expected to be the Saudi ruler who prepared for the inevitable transfer of power to a younger generation of Saudi princes. But rather than casting the net wide, he designated his nephew as the new Crown Prince—the first grandson of the founding King, Abdulaziz, to be so named—and his own young son Mohammad as Deputy Crown Prince, or second in line. The nephew is already well known in Washington: Mohammad bin Nayef, 55, has long been Interior Minister and run the Saudis’ counter-terror operations; he has twice met with President Obama in the Oval Office. But in selecting him, the king reached past hundreds of waiting princes.

“The model was kind of corporate leadership within a number of senior members of the older generation, and they didn’t always get along and they didn’t always agree, but they had a general corporate sense of where they wanted the country to go and it worked well for more than 50 years,” says Gause. “I thought the new king would try to recreate that kind of corporate responsibility across a number of people in the new generation, but that’s obviously not what Salman wanted. He’s privileged a couple of people and cut out a large number. And how that affects family cohesion down the line will be interesting to watch.”

For now, the war in Yemen, aimed at a Shi’ite rebel group advancing in the neighboring state, has provided a rallying effect at home. It also had the effect of forcing the U.S. to provide battlefield intelligence and targeting information (“not to support them would leave the relationship with no content,” says Freeman). But the fundamental problem remains Iran, the Saudis’ great regional rival. Riyadh feels threatened not only by Tehran’s gains in Iraq and Yemen, and continued support for the Assad regime in Syria, but—even more—by Obama’s engagement with the Iranians. Along with fellow members of the Sunni-dominated Gulf Cooperation Council, they feel threatened by the attention Washington is paying to Iran, in a region where attention equals prestige, or even license. Already almost wholly reliant on the U.S. for their defense, the Gulf Arab monarchs are asking for a formal treating with Washington guaranteeing their protection, something Obama officials say they cannot provide.

“I think their fears that we are going to just throw them over and that Iran will be our big ally in the region are greatly exaggerated,” says Gause. But those are the fears that prompted the Obama administration to convene the Camp David summit. And if King Salman cannot make it, Freeman says, he may have sussed it out as a “pseudo-event.”

“The Saudis and others have learned from Israel that you can give the United States the bird,” says Freeman. But that, the former ambassador adds, may work out for the best at Camp David. “Having the two Mohammads—bin Nayef and bin Salman—in this thing puts the two people who are actually running things in there. So if there’s something that’s actually going on in Saudi Arabia, these are the two who can make things happen.”

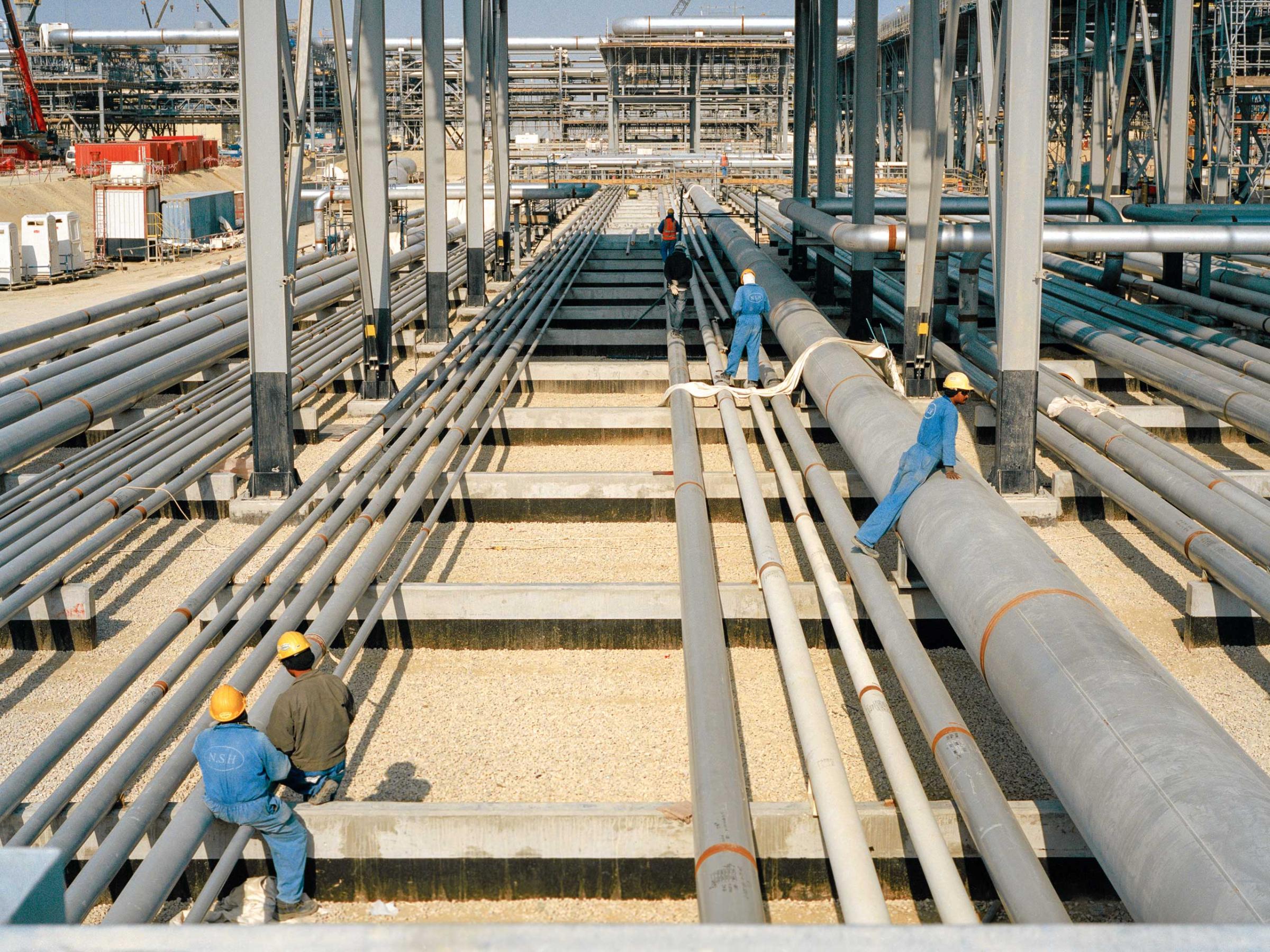

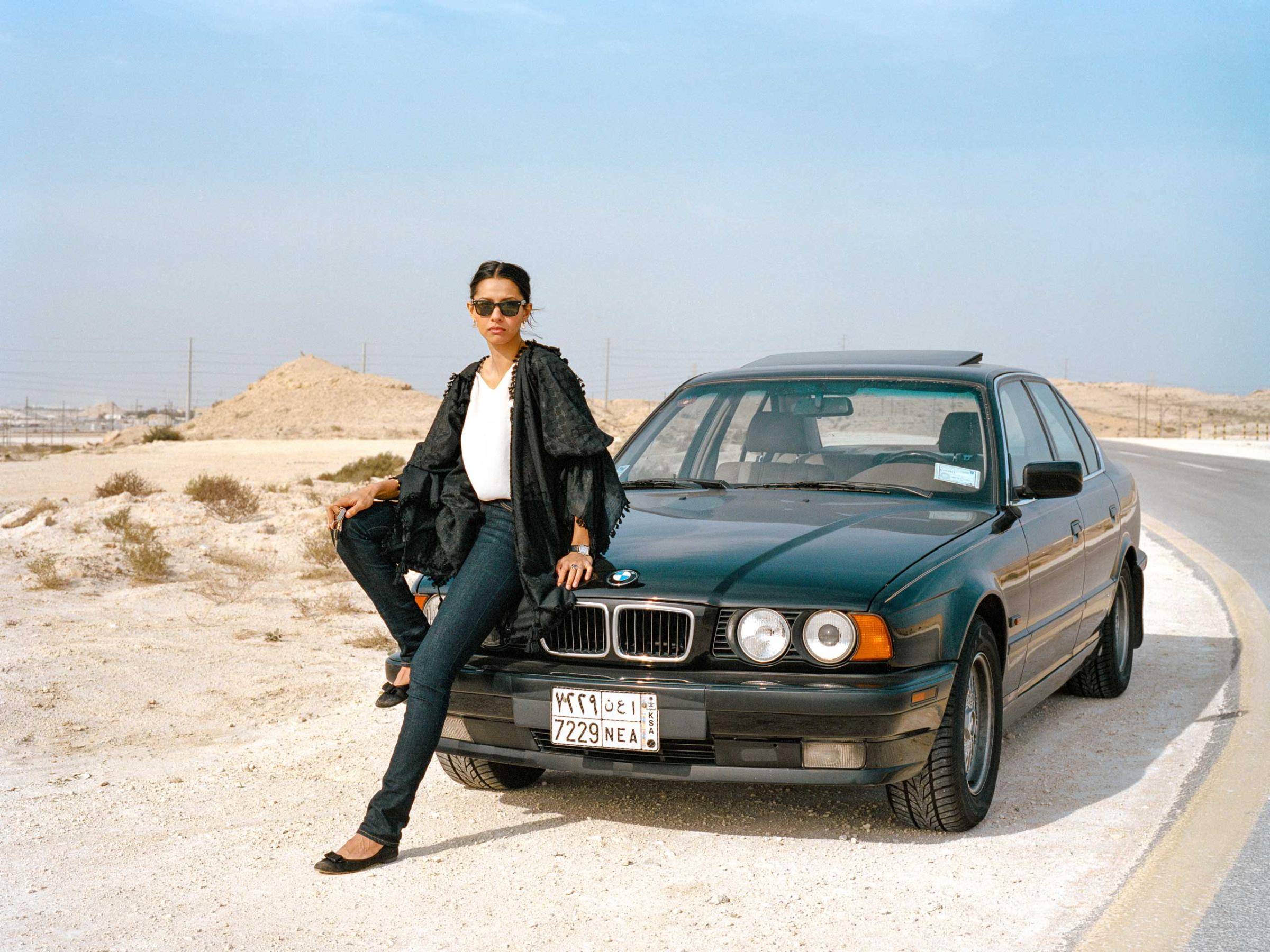

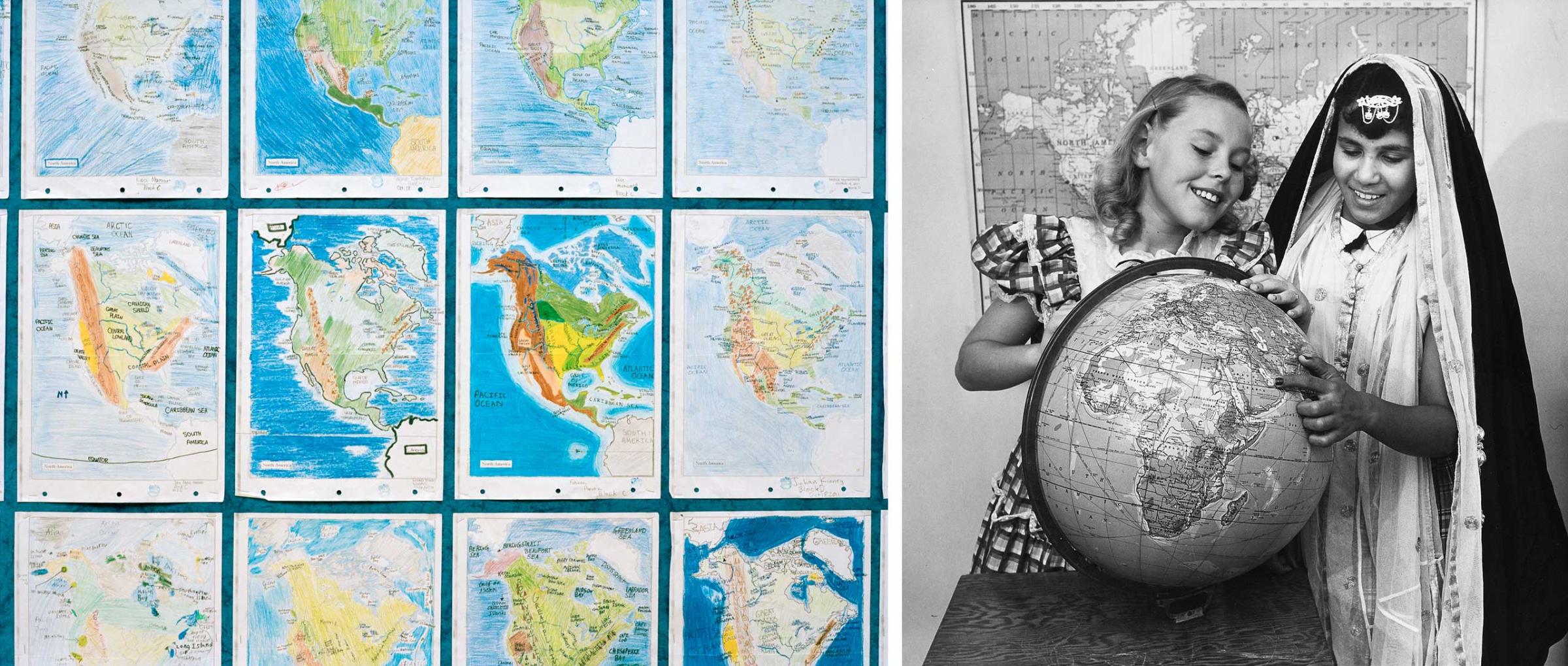

Inside a Saudi Arabian Oil Giant's American Oasis

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com