Let’s talk about The Witcher 3: Wild Hunt, an obscure sounding fantasy roleplaying game you’re either here reading about because you’re a bona fide Witcher wonk, or that you stumbled into after President Obama unexpectedly namechecked the series while visiting Poland last June (no really, he did).

For those in the latter column, a quick review. The Witcher games stem, some might say improbably, from several fantasy novels and short stories written by Polish author Andrzej Sapkowski in the early 1990s. The series concerns a potion-drinking mutant named Geralt, the eponymous “Witcher,” who hunts monsters for a living. Though Geralt is portrayed as apolitical, elaborate political plots eventually emerge in both the novels and games, forcing Geralt (and in the games, therefore, players) to grapple with ethical dilemmas that mirror contemporary real world ones.

Think Western fantasy, but through an Eastern European lens—more folkloric Brothers Grimm than epically biblical Tolkien. Think political intrigue, character depth and world building on par with HBO’s Game of Thrones. And in The Witcher 3‘s case, with CD Projekt Red finally jumping the series to a fully open world, think grand on a scale that surpasses the term. Think post-Skyrim.

I’ve had the game for less than a week, and don’t ask me how far along I am, because at two dozen hours, I’ve yet to see its middle. But I’m having a blast. It’s not perfect, and at points (see below) it can seem obtuse, but hour for hour, I’m happier with it than I was Skyrim—and at the 24-hour mark I was still pretty chuffed about Skyrim.

My impressions of the game so far, running the PlayStation 4 version:

The engine under this hood is pretty sporty

You think I’m talking about the graphics? In a moment. I’m referring to load times—the time it takes for a game to cycle up—because they’re crucial when you’re restarting from save points, say you keep whiffing fighting a mini-boss. The Witcher 3‘s load times are partly obscured by narrative recaps, but still unusually quick. When you figure the game’s juggling a play-space bigger than either Skyrim or Grand Theft Auto V‘s, one that’s seamless once it’s up and running (there’s no scenery pop-in) whether you’re wandering in and out of buildings or plumbing underground dungeons, it’s no small triumph.

And it’s visually stunning

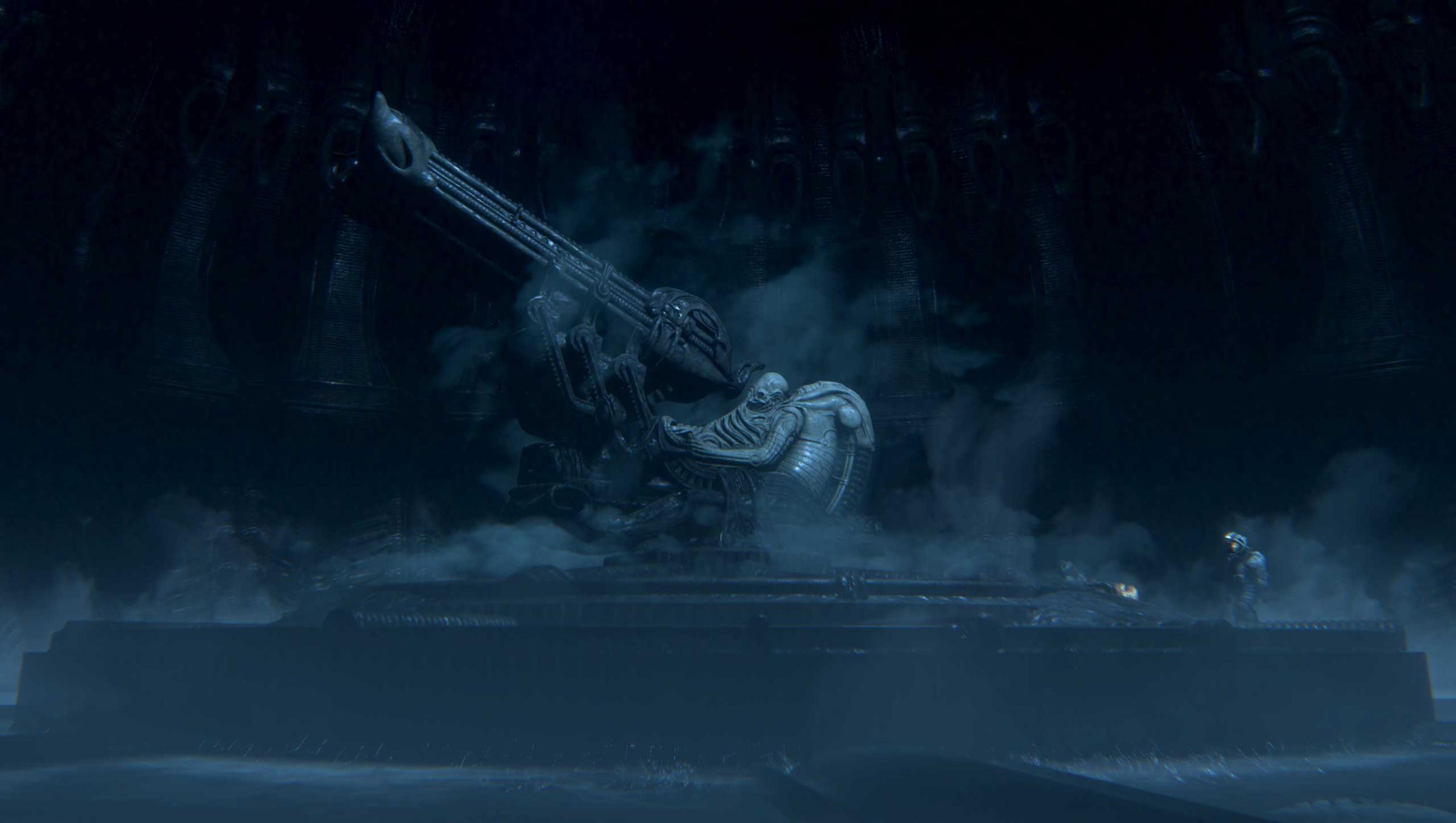

I don’t mean technically, since we’re accustomed to games that deftly model bosky sandboxes with resplendent cities and chaotic ruins and endless subterranean haunts. I’m talking about who made the game (CD Projekt Red, headquartered in Poland) and what informed their visual worldview. Put it this way: The Witcher 3 looks nothing like Skyrim or Dragon Age: Inquisition.

Speaking as someone who’s spent months in Poland, the Baltics and Russia, it feels more like that. Light cuts chiaroscuro columns between swathes of stormy blackness draped over fir and oak forests punctuated by meticulous medieval structures and grass-choked wagon wheel roads. The wind knocks stands of trees and patchy scrub around like shaken springs, and cloud-fog hangs off foothills and mountains in wispy skirts. It feels older and creepier, but also elegiac and incredibly beautiful, if that makes sense (speaking as an American who’s probably doing the whole romanticizing-the-other thing).

How do you convey to someone what a blood-red, storm cloud framed, lighting-flanked sunset looks like if you happen to come across one tromping through Poland’s Lower Silesian Wilderness? Show them a sunset in The Witcher 3.

Deceptively conventional quests morph into delightful rabbit holes

Tired of running delivery boy errands and “go kill X monsters” treks designed to fill out space in games like this? You’ll still find them here, but the design team threw in heaps of meaningful wrinkles, upending tropes by extending the backstories to quests and folding in deductive sequences that drawn upon your extrasensory abilities (some can be over a dozen steps long). And when they can’t do that, they’ll just send you on quirky goose chases with surprise denouements to keep you off balance.

And that’s what it’s really about when you’re crafting challenges for players, isn’t it? Preserving an air of mystery and situational novelty? Developer CD Projekt Red has worked to thwart conventionality since it launched the series, and you can see it shining through any one of The Witcher 3‘s idiosyncratic missions.

The scripted encounters soar

Someone needs to write about the real war, says Geralt at a point early in the game, “not colorful banners or generals making moving speeches, but rape, violence, and thoughtless cruelty.” He’s chatting in a tavern with an academic who’s just explained what’s driven him out to the front, to chronicle the war.

“Rape and cruelty are details of no import to the war’s course, trinkets on the garment of conflict you might say,” replies the academic, betraying a kind of dangerous, elite romanticism, as well as callous disregard for Geralt’s vaguely antiwar position.

It’s an uncomfortable moment that could stand for any other in the game, an exchange that’d feel at home in a George R.R. Martin novel, and one that’s still sadly unusual in a video game, where incisive much less subversive writing takes a backseat to anodyne platitudes about war, or whatever else (one of gaming’s great mistakes has been its cooption of the false dichotomy between authorial intention and player control).

But not The Witcher 3, where beautifully voiced and philosophically provocative interactions are the norm for virtually every encounter in the game, be it part of the main quest or any of the secondaries. True, The Witcher 2 already showed us that CD Projekt Red could write, but The Witcher 3 pulls that level of depth off in a game world that’s exponentially bigger. It’s like stumbling into a strange, baroquely ornamented wine cellar stuffed with vintage bottles, every one.

And each location feels unique

Every rutted path, split-rail fence, thatch roof, copse of trees, bricked ruin, walled village and corpse-haunted battlefield feels handcrafted and one-of-a-kind, and you can wander for hours without repeats. Imagine the time it must have taken, given how vast The Witcher 3‘s play space is, but what a visual payoff and triumph. You could write plausibly poetic travelogues about the game’s distinctive vistas, whether sloshing through Crookback Bog, taking in the heart stopping view from Kaer Gelen castle, hiking around the craggy monster-thronged foothills of Bald Mountain, or getting lost in the wonderfully nuanced architecture of metropolitan Novigrad.

But the world’s also stuffed with vacuous nobodies

Cities and towns are choked with citizenry going about their scripted business, and you can chat with any of them. Trouble is, almost no one has much more than a catchphrase to work with. Wander through a village and you’ll be assaulted by “talk” prompts, but tap to do so and you’ll be treated to a barrage of boilerplate-isms: “Yes?” “Erhm?” “Step away.” “Nordling?” “Hm?” “What do you want?” “Tidings from Vizima?” Et cetera.

Conversational window dressing just wastes precious time in ginormous games like this. Better to disable that level of interactivity outright and let the ambulatory props shuffle through their subroutines. Save talking for situations that involve actual talking, in other words.

And the interface needs work

Getting Geralt to properly interact with something, say another person or chest of goods, feels a little fiddly, requiring too much sidling up or scooting backwards to conjure the prompt.

The way things are labeled also feels a little lazy: When you’re out gathering flora for The Witcher 3‘s alchemy game, for instance, the prompt you’ll see is generically “Gather Ingredients,” instead of a more helpful “Gather [name of ingredient].” Why ask players to stop and pull up a dialogue box, when you could more readily specify what they’re looking at as they wander by?

Combat can be quirky

I love The Witcher 3‘s third-person battle ideas for the most part–a mix of swordplay and tactical spellcasting that mostly works–but two things stand out as sore spots.

The game binds your ability to “parry” in battle to the same button that triggers “Witcher Sense” out of battle (it’s an extrasensory ability Witchers use to “see” thing others can’t). The problem is that you’re sometimes shuffled out of, then back into, combat mode so fast that you grab the button to parry, but invoke the other ability instead, laying you open to blows.

The other issue, a little more serious, is the way targeting works. The system as it stands lets you focus your attention on different opponents by flicking the right thumbstick while you maneuver with the left one. But the game’s enemies often reposition themselves so quickly, and often assault you in close-in rows, that it’s all too easy to accidentally target the guy right behind the one you want to hit, which causes you to attack past the front line and open yourself up to unblockable flank damage.

The world itself, though gorgeous, has shortcomings

Spatial physics? Who needs ’em! Instead of building off basic line of sight principles, where you might use ledges or walls or giant trees to sneak up on an opponent, enemies simply “sense” you through plainly obfuscating geometry. They’ll even brokenly fire arrows through trees, either a glitch or collision detection oversight that outs the environment as a facade in combat. Less ambitious open-world games manage to pull this stuff off competently, so why not The Witcher 3?

(For that matter, why can’t Geralt sneak? I’m not asking for Thief or Dishonored or Assassin’s Creed here, but Witchers aren’t tanks, and Geralt’s surely capable of creeping up on squads of foes, so why can’t he at least attempt to here?)

And despite its delays, the game still has bugs

My first two matches of Gwent (a semi-interesting collectible card game you can play with other characters in the game for money) crashed the game hard. And while hanging out in a tavern, a horse (not mine) outside wandered over and stuck its head through the tavern wall—creepy for all the wrong reasons.

See The 15 Best Video Game Graphics of 2014

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Matt Peckham at matt.peckham@time.com