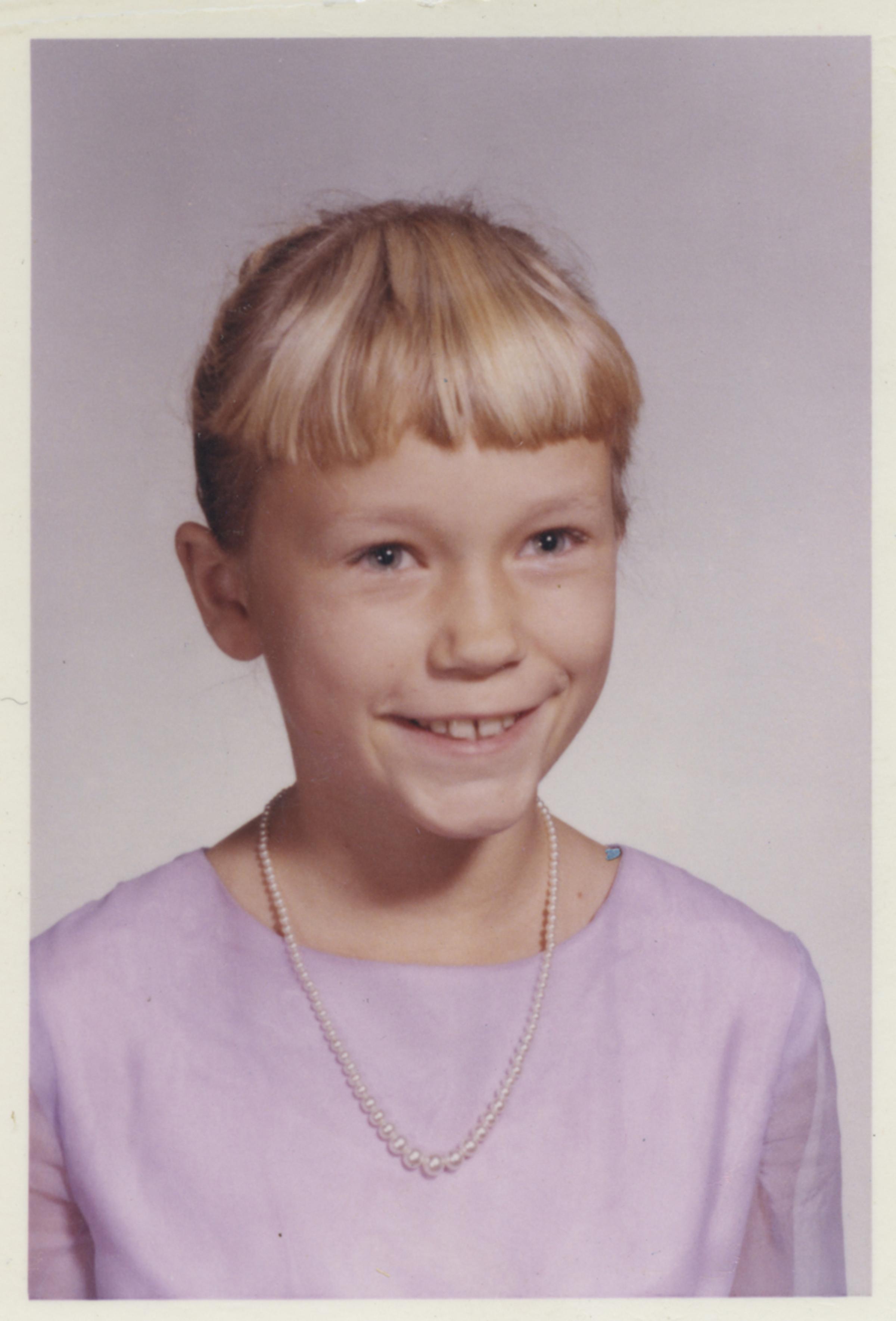

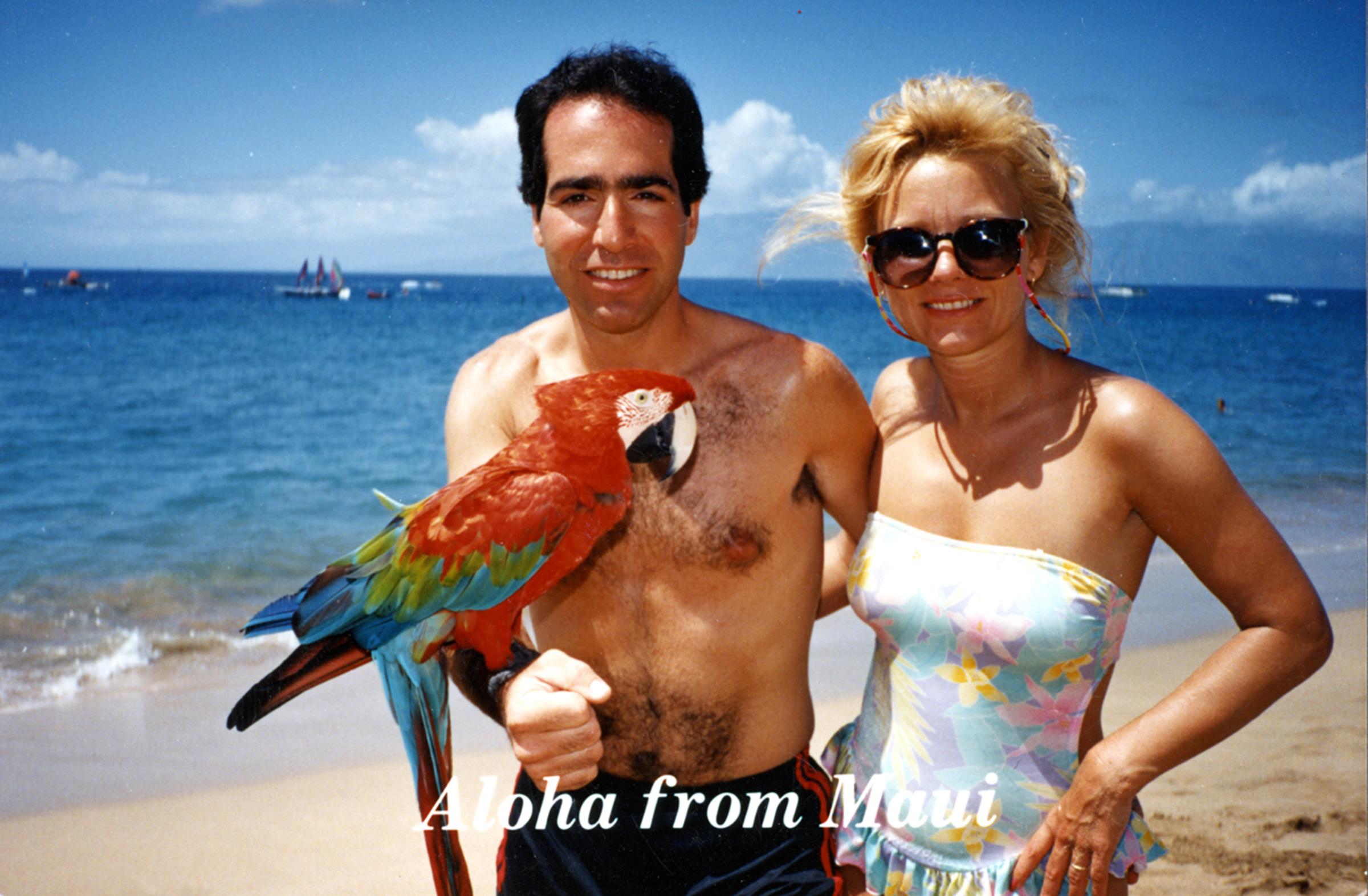

Melissa Spitz was only six when her mother Deborah was institutionalized for psychotic paranoia, while her father was away on an overseas trip, leaving Spitz and her brother at friends’ homes. Over the years, her mother’s diagnoses changed frequently—from personality disorder to alcoholism—eventually rupturing her family.

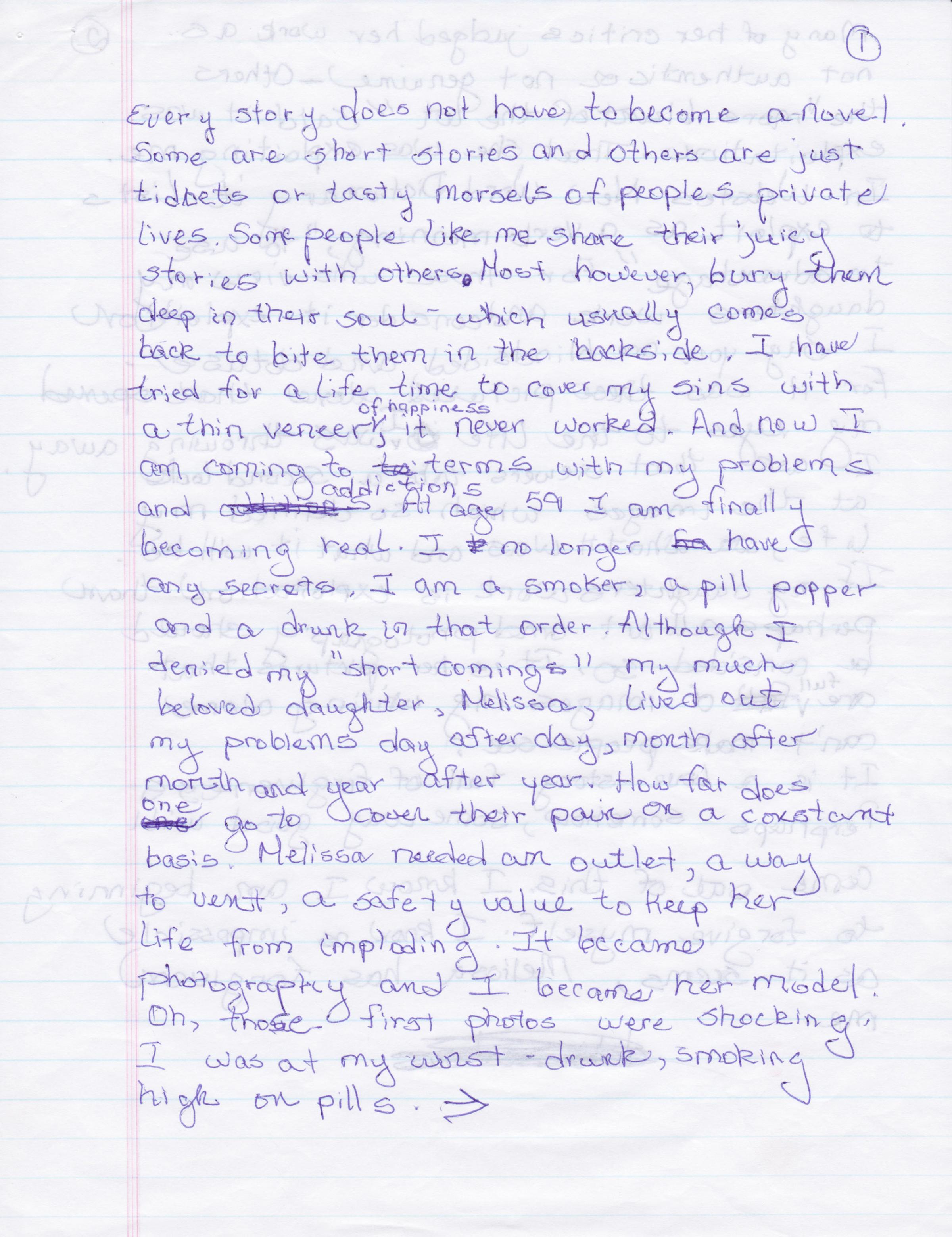

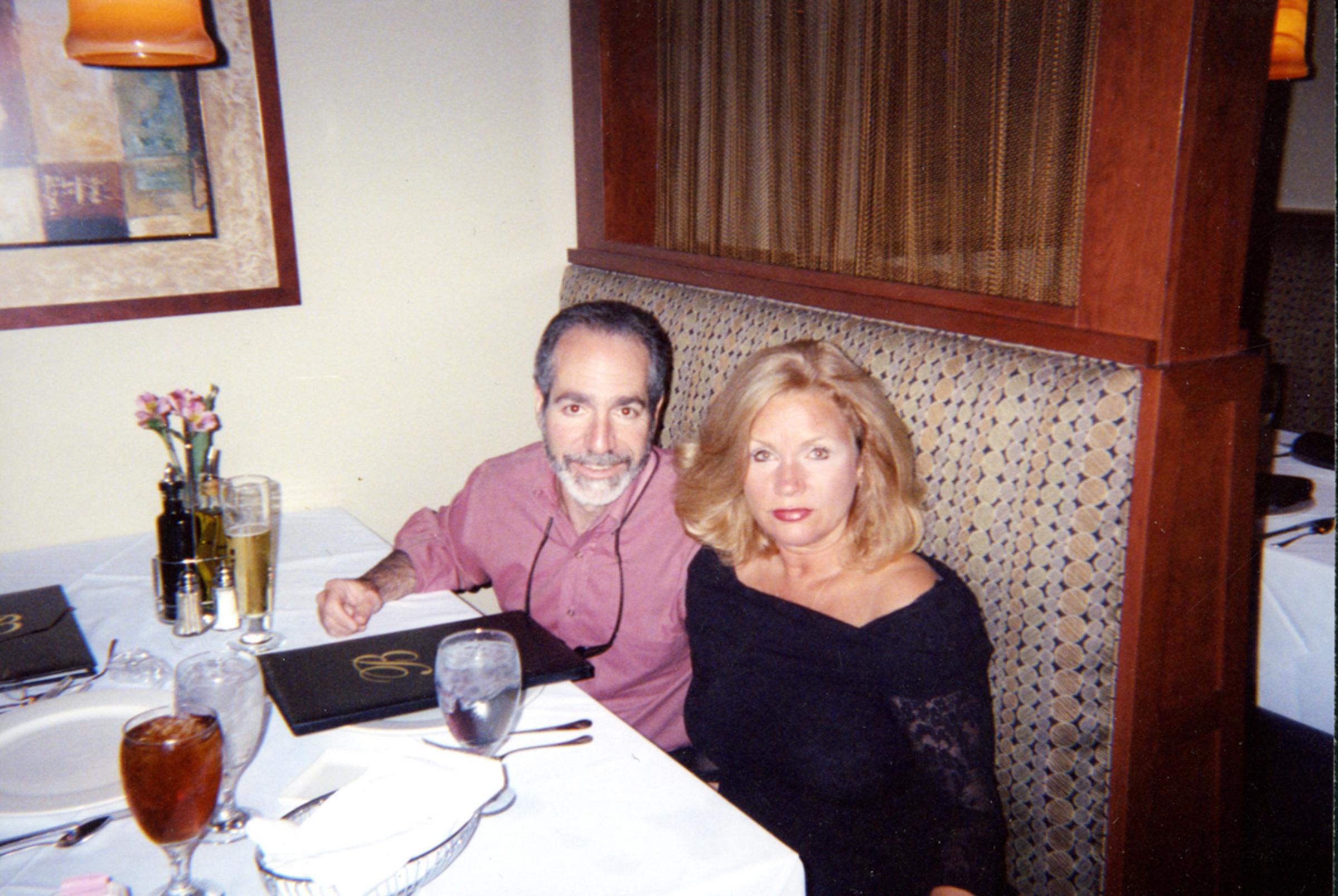

“My mother has caused our family a lot of pain over the years,” Spitz says. After her parents ended their 27-year marriage and her father left their home in St. Louis, and her brother Adam became more estranged because of his mother’s behavior, Spitz became the primary caretaker, traveling home every other week while juggling her photography studies at the University of Missouri in Columbia, Mo., and later during graduate work at Savannah College of Art and Design in Savannah, Ga. in her early 20s. Inevitably, her mother became her central focus.

“My [photography] background and this project are kind of blended, and it was this thing that happened in unison,” the 26-year-old photographer tells TIME.

Spitz did not think that documenting her mother could make a substantial body of work until she saw the similarly intimate and intriguing photographs of Richard Billingham, Nan Goldin and Tierney Gearon, who unapologetically exhibited the private lives of their loved ones in a public display. “I really wasn’t aware that that was something photographers did.”

Yet, to fully confront the moments of chaos and, at times, ugliness of life — emotions often concealed outside of close family circles — was a difficult journey. When Deborah was hospitalized after a car accident and begged Spitz to document it, she couldn’t raise her camera. “I remember telling her that this makes me feel bad, like I’m doing something wrong,” Spitz says.

But as time went by and hospital visits stacked up, Spitz says that Deborah told her: “This is my life, Melissa. If you’re going to do this, you need to just go all in.” Since then, her mother has become more than just a subject; she’s a collaborator. The experience has served as an emotional and therapeutic bridge between the two, channeling a relationship that had long faltered. “Now I can’t think of a time that I haven’t photographed her, even when she’s been in hospital. I just try and let her have as much control as possible.”

Once, Spitz took her mother back to the high school where Deborah had been a popular cheerleader, and sat her down on the bleacher for a portrait. “She just started screaming and crying,” Spitz recalls, “It was really fake at first but she kept doing that, and all of a sudden [she] had this tone that was just so real and full of pain.” In that moment, Spitz’s own long-repressed emotions about her mother’s illness erupted. “That was when I knew that the work was a conversation that was not only me watching her but also an echo of how I feel about living and dealing with her.”

But as the world of photography opens doors to self-reflective and sensitive examination, accusations of exploitation also arise. And Spitz understands how turning the lens on her mother can affect Deborah’s behavior.

“I am fully aware that my mother thrives on being the center of attention and that, at times, our portrait sessions encourage her erratic behavior,” Spitz says. “There are people who think I exploited my mom, and think that I’m doing something wrong, and then there’re people who think I’m doing something very important.”

“My hope for the [story] is to show that these issues can happen to anyone, from any walk of life and that there is nothing to be ashamed about,” she adds.

Now, Deborah, 60, works as a greeter at a Home Depot store in St. Louis, a job created by Missouri’s Social Security Disability Insurance program. She tells TIME that she hopes sharing her story could help de-stigmatize mental illness. For the photographer, the investment on a project, which already stretched half a decade and is still ongoing, is worth it. “I can finally take something I love doing and share it with my mom,” she says. “It’s been a mirror for both of us to see our lives.”

Melissa Spitz is a photographer who divides her time between the Midwest and New York. She plans to make a book about her mother’s project, You Have Nothing to Worry About. You can also follow her on Instagram.

Paul Moakley, who edited this photo essay, is the deputy director of photography and visual enterprise at TIME.

Ye Ming is a writer and contributor to TIME LightBox. Follow her on Twitter and Instagram.

Listen to the most important stories of the day.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com