Is it possible to experience survivor’s guilt for a travesty that took place decades before your time? I ask because I am plagued with the feeling on a regular basis.

During the weekend of Freddy Gray’s death, I embarked on a family vacation that prompted a visit to the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, Tennessee. That visit made me aware of the recurring guilt I feel for being black in America and going through life complacently while millions have died just so that I can live.

My experience at the museum most certainly was not the first time I’ve dealt with such looming pain and regret for the tribulations endured by those before me. In fact, I often feel it when I’m confronted with the horrid facts of the past in which American society chose to see African-Americans as subhuman, therefore proceeding to treat them as such. Movies, autobiographies, news clips, historical documents, or simple conversations have a way of putting me in existential turmoil where I question why I get to live with this freedom when others didn’t, and still don’t.

As a black female, my life takes place pretty uneventfully. I sit at the front of a public bus nearly every day on my way to work, I am openly affectionate with my white partner in public, I get to rant about the status quo and government blunders without fear of repercussion from white listeners, and I’ve held managerial positions that have allowed me to delegate work to all races and creeds. And yet, I still can’t help but fall into feelings of despair and depression when I think of the surfeit of people who had to die just so I could enjoy these seemingly miniscule luxuries.

The National Civil Rights museum is an awe-inspiring experience that every soul should experience. It’s a walk through time during America’s gestation, where social mindsets were incidentally at their most outwardly heinous. Through a series of rooms, visitors of the museum trace the roots of African-Americans. The first room focuses on the arrival of enslaved Africans packed together like rotting fish in a tin can within The Middle Passage, before delving into our political liberation and current ongoing struggles with economic divide based on racism.

Interactive buttons are pushed to detail the individual stories of slaves who fought against the early American system. Phones can be pulled out of sockets for visitors to listen to someone’s recorded personal tales of life under Jim Crow rule. Mementos, artifacts, and documents showcase the systematic elements in place meant to dehumanize and subjugate blacks over the centuries. Clip footage shown on the walls become visual reminders of our daunting past where blacks endured public beatings and humiliation, all because they wanted the freedom to get served at local diners and restaurants.

The museum’s tour ends in the glass-encased Lorraine Motel room where Dr. Martin Luther King spent his final moments before getting shot in the face, ending his life and the hopes of a brighter future for many at the time.

Despite these heartrending relics, The National Museum of Civil Rights captures a feeling of comradery and perseverance in every room. While the trip down memory lane is a brutal one, each room ends on a note of triumph and victory.

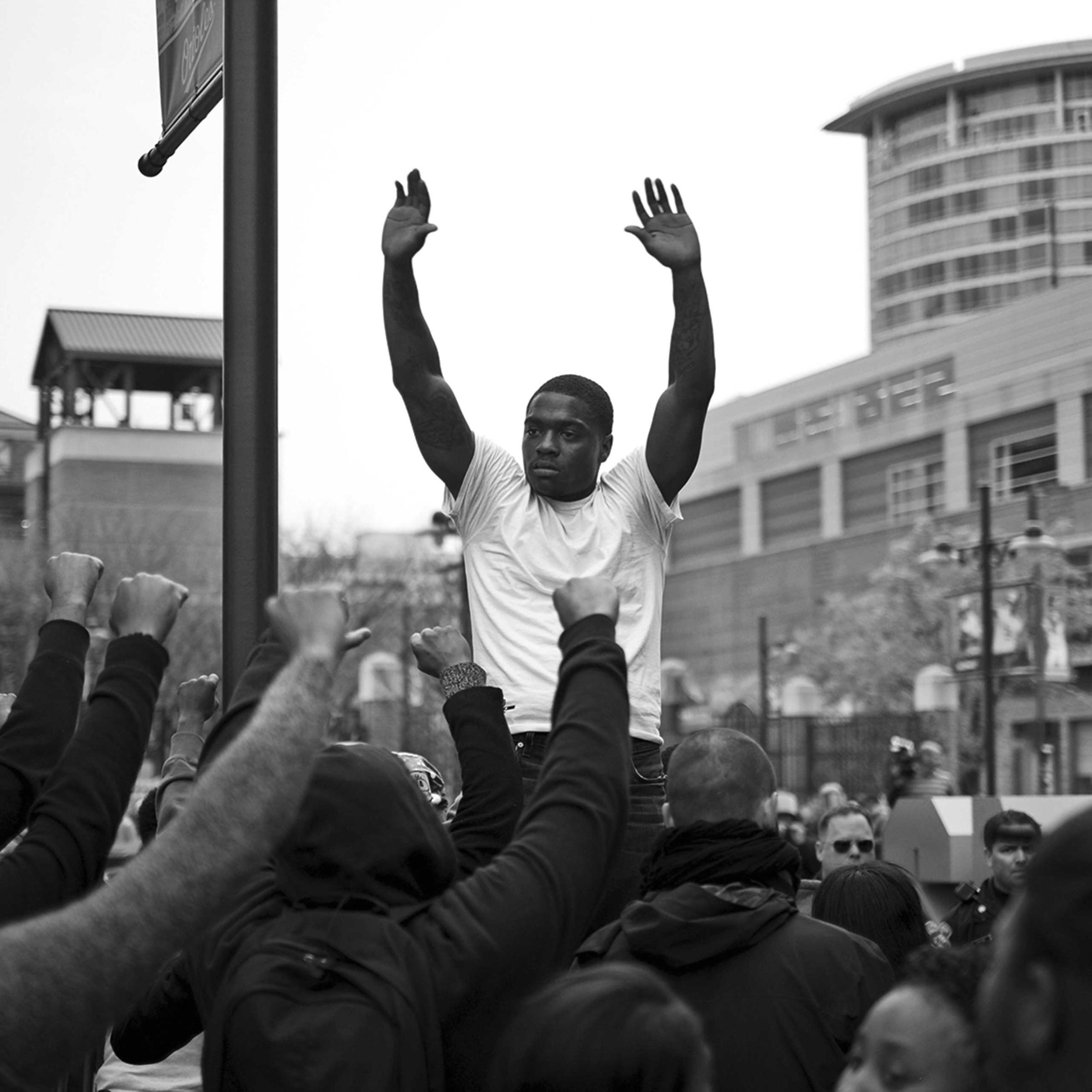

Yet, still I couldn’t help but succumb to the pain, and not just the regret for what was, but the sadness for what still is. This was only exacerbated a day later when a television broadcasted the angry rioting faces in Baltimore at the wake of yet another innocent black man killed by authority figures.

Each person of the past who chose to fight against the system in place had it much worse than me. They were willing to lose their lives for the prospect of a better future for blacks. They succeeded in immense ways and I gratefully praise their victories.

But, what am I doing to preserve that? What are we as a society doing to compensate for their struggles? I now have the freedom to be complacent in life and do nothing except gripe about pop culture and social ills online if I want, we all do. But it’s not enough.

The National Civil Rights Museum reminded me what sparks my unquenchable desire to fight for others who don’t receive the same privileges as me. I want to pay it forward and send my condolences to the memories of the past through persistent action because otherwise, what was the point of their deaths? Why should I deserve a life of freedom when someone who was hung for speaking out didn’t get to? What good were their deaths, beatings, shamings, or exclusion of rights if black men are still being killed and incarcerated at alarming rates? Minorities are still underrepresented and their issues are still largely ignored. When authority figures get away unscathed despite having innocent blood on their hands, we as a society are obviously doing something wrong.

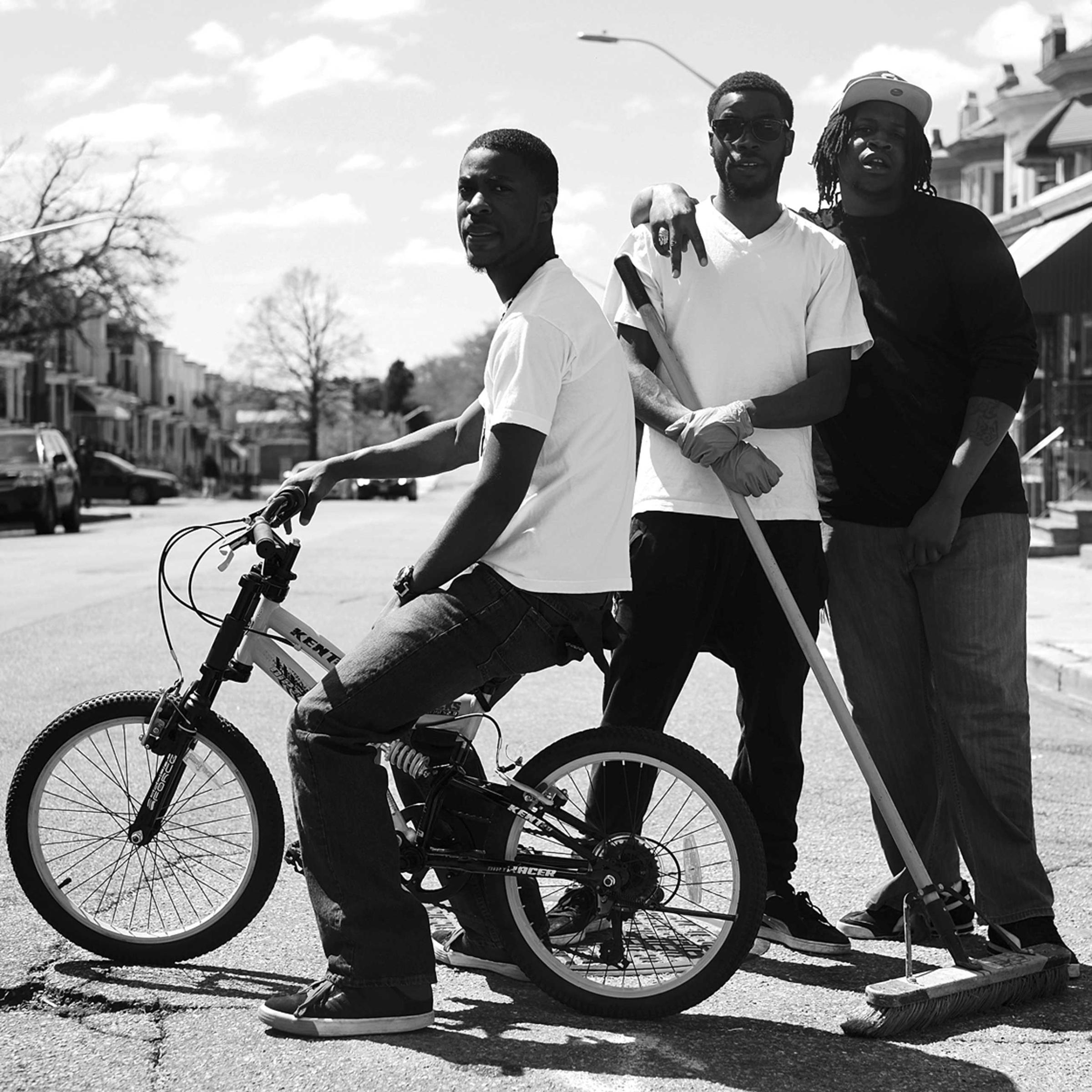

Baltimore, Ferguson, and all the underprivileged cities that riot in the face of racial tragedies shouldn’t be viewed as “thugs” riding the wave of anger and creating chaos. Instead, they should be seen for what they are: people who don’t know how to avenge the wrongs of the past time and again and aren’t sure of what else to do.

I understand the rioters. I get the anger. If my friend, family member, or acquaintance is murdered in my area for being black on the wrong day, I can’t guarantee that my level-headed rationale would hold up.

Even though the six officers involved in Freddie Gray’s death have been charged, we have yet to free our nation of a brutal reality in which the oppressor reminds minorities of their lack of power through violence and death. Similar to Jim Crow days, blacks are expected to accept whatever happens to us and stay in our place, and to not smash windows or throw rocks at cops in retaliation. Nevertheless the rioters want what millions of us, race aside, want: some type of retribution and an end to the pain, torture, and death that exists within the cycle of injustice that continues.

For every unarmed person of color shot by a police officer, for every minority working in terrible low-wage conditions, for every child of color growing up in impoverished areas lacking the basic resources to excel, for every school lacking the funds to provide basic education, for every starving human: I long to take a standing personal interest to fight to end these social and cultural ailments. My need to do so is for those who came before me, who fought for my rights before they could conceive of my existence. If I can’t use what I have to make a difference and continue the fight for justice for all, then I don’t see a point of enjoying a life of liberty.

Quatoyiah Murry wrote this article for xoJane.

Go Behind TIME's Baltimore Protest Cover With Aspiring Photographer Devin Allen

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com