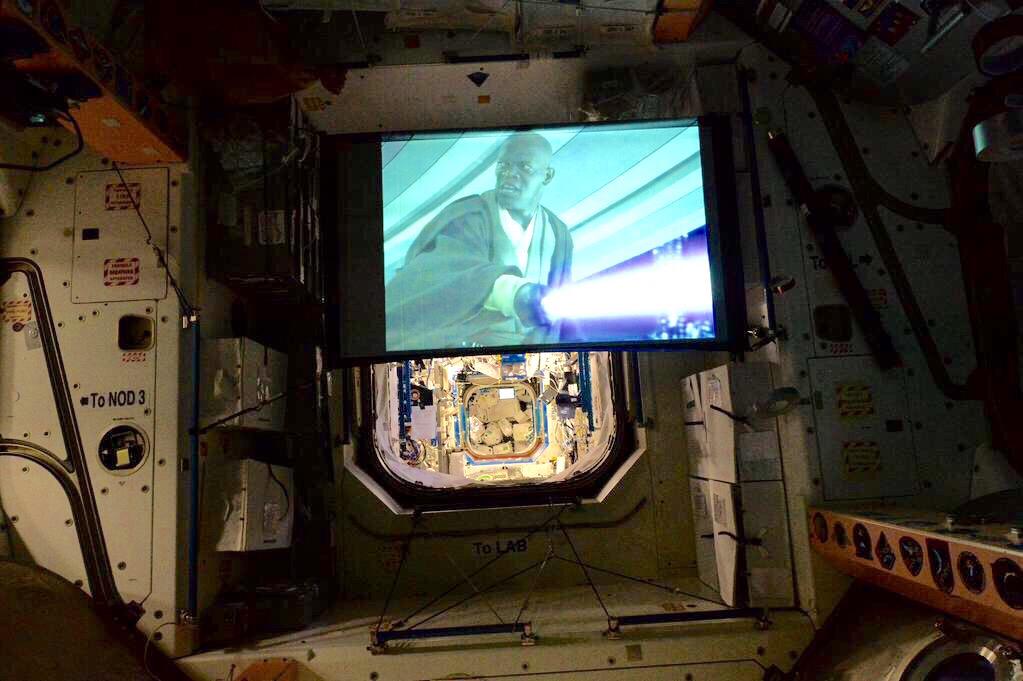

Think you’re cool because you hosted a Star Wars-watching party on May 4, a date that is recognized as Star Wars Day? Well, you’re not as cool as you think. Watching Star Wars on May 4 when you’re 250 miles above Earth, orbiting the planet aboard the International Space Station (ISS), now that’s cool. That’s how year-long space travelers Scott Kelly and Mikhail Kornienko, along with the other member of the ISS crew, spent a few hours of downtime on Monday.

The ISS is not without these Earthly grace notes. There were tacos—or the closest approximation of them when you’re using rehydrated food—the next day, in honor of Cinco de Mayo. And there was espresso, thanks to a just-delivered machine—dubbed the ISSpresso—which Italian astronaut Samantha Cristoforetti set up and tried.

“Coffee: the finest organic suspension ever devised,” she tweeted. “Fresh espresso in the new Zero-G cup! To boldly brew…”

But there’s a lot more than good food and good films happening on the station this week—and, as with every week, much of it involves good science. Take the mouse studies, which are routinely conducted in orbit but take on special importance in the context of the extensive biomedical research that is at the heart of Kelly’s and Kornienko’s marathon stay.

Mice don’t care for being in space—at least it stands to reason they wouldn’t since zero-g can be as hard to manage for them as it is for human beings and they spend a lot of time in their enclosures just trying to gain purchase on something that’s standing still. Conducting experiments on them is harder too, since the last thing you want to do is open a habitat just anywhere and have an escapee drift free and get lost. So mouse enclosures must be anchored on an experimental rack, lights, fans and power connectors have to be engaged, and food bars have to be provided to keep the mice distracted as the work gets underway.

The research focuses on the animals’ skeletal, muscular, immune and cardiovascular systems—all of which can go awry in humans exposed to extended periods in zero-g. But unlike human subjects, mice can be, well, sacrificed and dissected to provide more detailed looks at what’s going on inside them. Other, less lethal sampling like blood draws can also be conducted. Sample extraction is a big part of what the ISS crew-members working on the mouse studies are doing this week, preparing the tissue to be brought home aboard the SpaceX cargo vehicle when it returns to Earth later this month.

Cristoforetti is spending part of her week working on the straightforwardly if unartfully named Skin-B study, which involves analyzing cells and tissue samples to determine why human skin ages so much faster in zero-g than it does on Earth. That should not happen, since much of what causes the ordinary stretching and breakdown of skin is gravity, which is not a factor in space. But what should happen and what does happen are often two different things in science, and Cristoforetti is working to learn why.

The purpose of the work has nothing to do with human appearance. Skin is the body’s largest organ and it pays to know why it suffers so much in zero-g before sending astronauts on missions to Mars that could last more than two years. Both in space and on the ground, what’s learned from Skin-B could also provide insight into the functioning—and malfunctioning—of the body’s other organs, especially the ones lined with epithelial cells, the type of cell that makes up the skin.

American astronaut Terry Virts, the current commander of the ISS, is busying himself in the Japan-built Kibo module, getting ready for the next round of Robot Refueling Mission-2 (RRM-2) exercises. RRM-2 explores ways to repair, upgrade, and refuel satellites in orbit, using robots instead of astronauts to do the dangerous work. Satellite servicing was one of the big selling points of the space shuttle, and while the program as a whole never made that kind of on-call repair visit routine, some of the most impressive of the shuttles’ missions were the maintenance trips astronauts made to the Hubble Space Telescope. This week, Virts will be configuring the Kibo airlock so that the RRM-2 slide table and task boards can be positioned outside by the ISS’s Canada-built robot arm.

Least important to the station’s science objectives perhaps, but most important to its crew, are preparations Kelly and Virts are making to replace the filters that scrub carbon dioxide from the ISS atmosphere. Remember the scene in Apollo 13 in which the astronauts had to figure out how to make a replacement filter from cardboard, plastic bags and duct tape or they would suffocate on their own exhalations? The station crew doesn’t want to have to do that—so Kelly and Virts kind of have to get things right.

That’s the rub about any given week on the space station: the maintenance jobs can be routine—but only until they’re critical. The science can seem arcane—but only until it revolutionizes our knowledge of human biology. Kelly and Kornienko have 52 such weeks to do their otherworldly work, and the other crewmembers have up to six months each. The rest of us have forever to use the knowledge they bring home.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com