Savagery is harder than you think. As members of a highly social species, genetically coded for cooperation, compassion, and the powerful, nearly telepathic ability to experience what another person is feeling, we should not be terribly surprised that convicted Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev shed at least a few tears in court on Monday when his aunt took the stand in the trial’s penalty phase to plead for his life.

We like to think that our criminal monsters are just that—monstrous, somehow fundamentally different from the rest of us. And in some cases that’s true: serial killer Ted Bundy is often described as sociopathic, a man incapable of empathy. Movie theater shooter James Holmes is thought to be schizophrenic, a disease that can indeed leave people incapable of feeling.

But most of the time killers are people with the same emotional software as the rest of us. And just as happens with real software, theirs got corrupted somehow. When it comes to empathy, such a breakdown takes some doing.

The human brain is wired with so-called mirror neurons, brain cells that draw us together by causing us to experience similar things at the same moment. It’s mirror neurons that explain why yawns are contagious, why a newscaster’s sudden laughing jag makes you laugh too, why newborns—who have never seen themselves in a mirror and thus have no idea what their faces look like—will open their mouths wide when an adult does. Up to 10% of the brain’s neurons are thought to have mirroring properties, which is a measure of how important they are.

When Tsarnaev’s aunt took the stand, she began crying before she even spoke. When she did speak, she could manage to give only her name, her age and her place of birth before dissolving entirely and being allowed to step down. She was seated only 10 feet from her nephew, which made her a real and tactile presence.

Tsarnaev’s cool indifference, which has been on display throughout the trial, has seemed at least partly 21-year-old bravado—magnified many times over by whatever psychological journey he took that allowed him to commit the horrific crime he did, and magnified still more by the certain knowledge that his life is over, that he will either be executed or spend the next half dozen or so decades in a cage. It pays, at least in public, to maintain a certain numbness in the face of that reality, lest it become overwhelming.

But for a man-child who may be a horror but is not a Bundy, there are limits. Another person’s tears are limits. An aunt who, in a different time and place, would surely hug you is a limit. And mirror neurons—which populate the brain of the bomber as surely as they do the brain of the doctor or the mother or the person you love—are limits too. Tsarnaev ran out of emotional room today, and the sorrow he felt is just a small part of a penalty he will pay for many years.

Read next: Boston Bomber’s Teacher Says Tsarnaev ‘Always Wanted to Do the Right Thing’

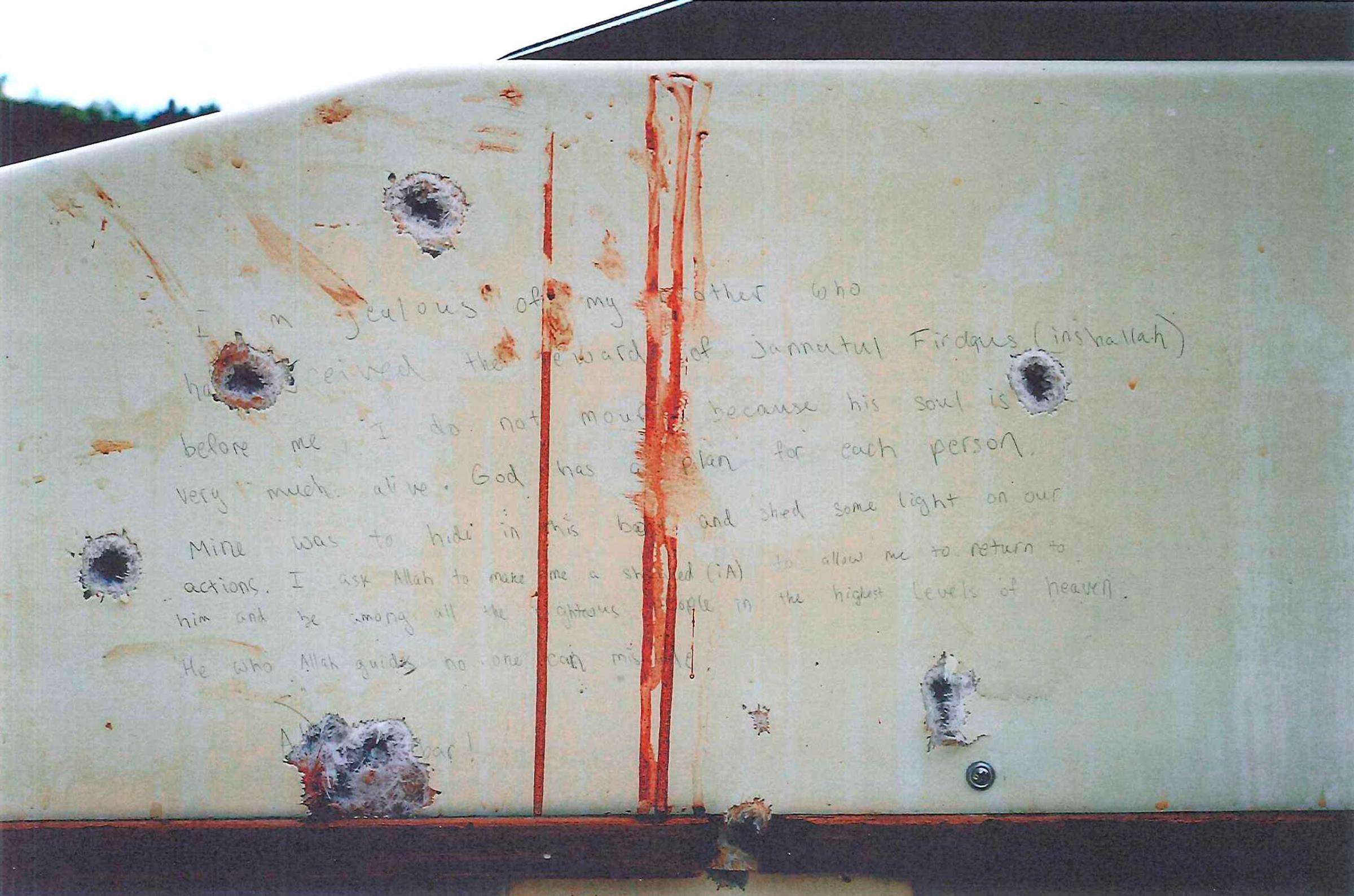

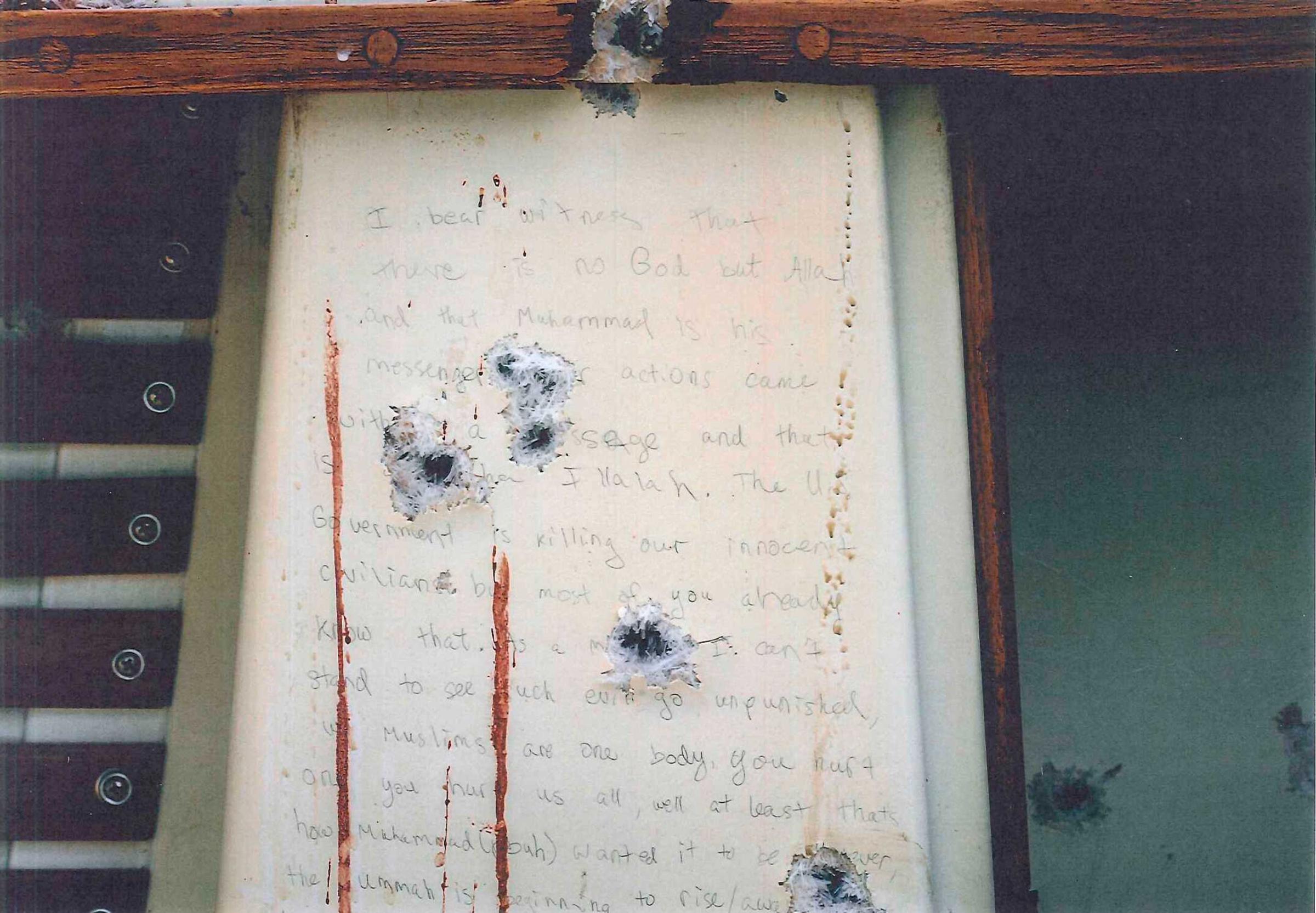

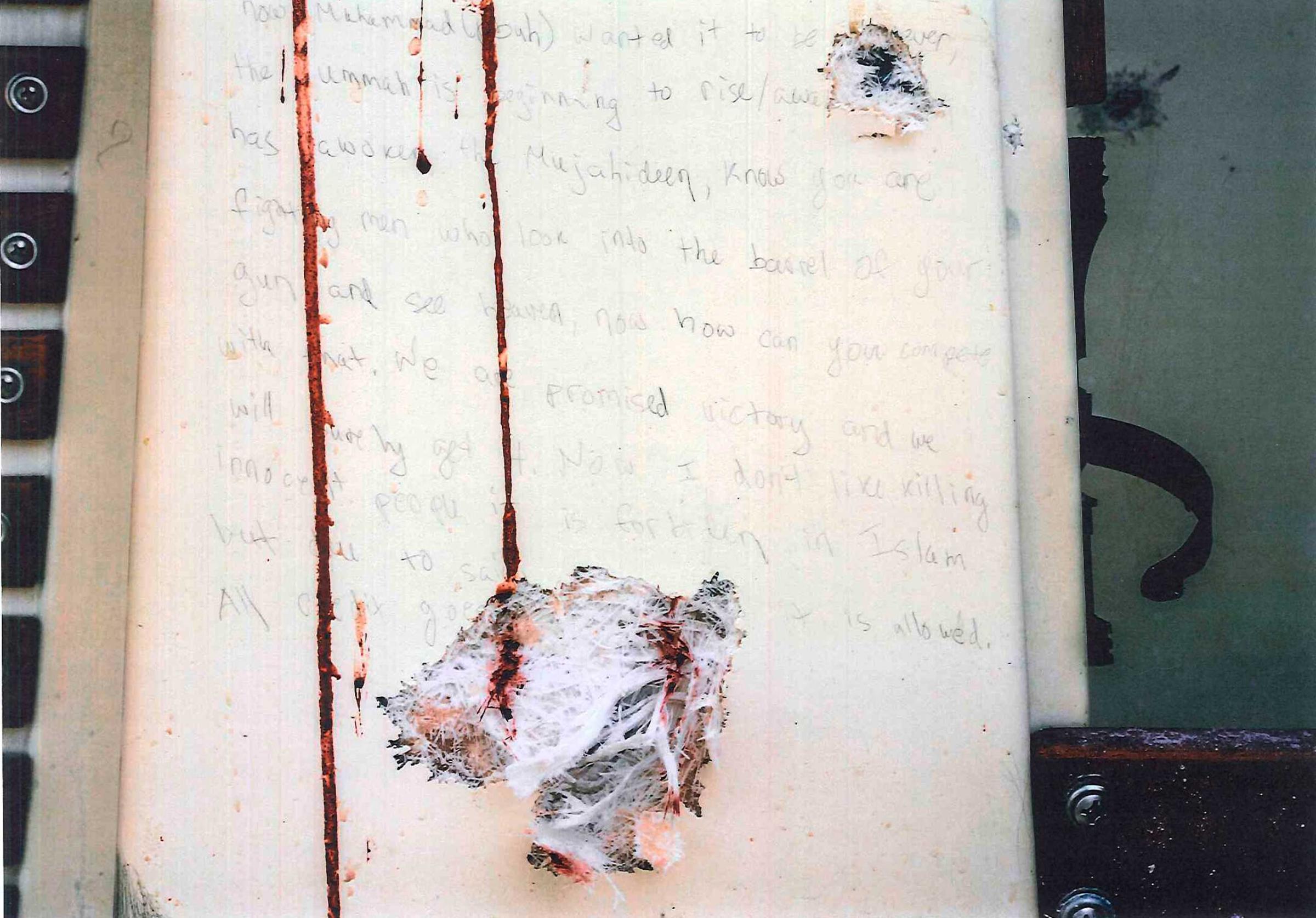

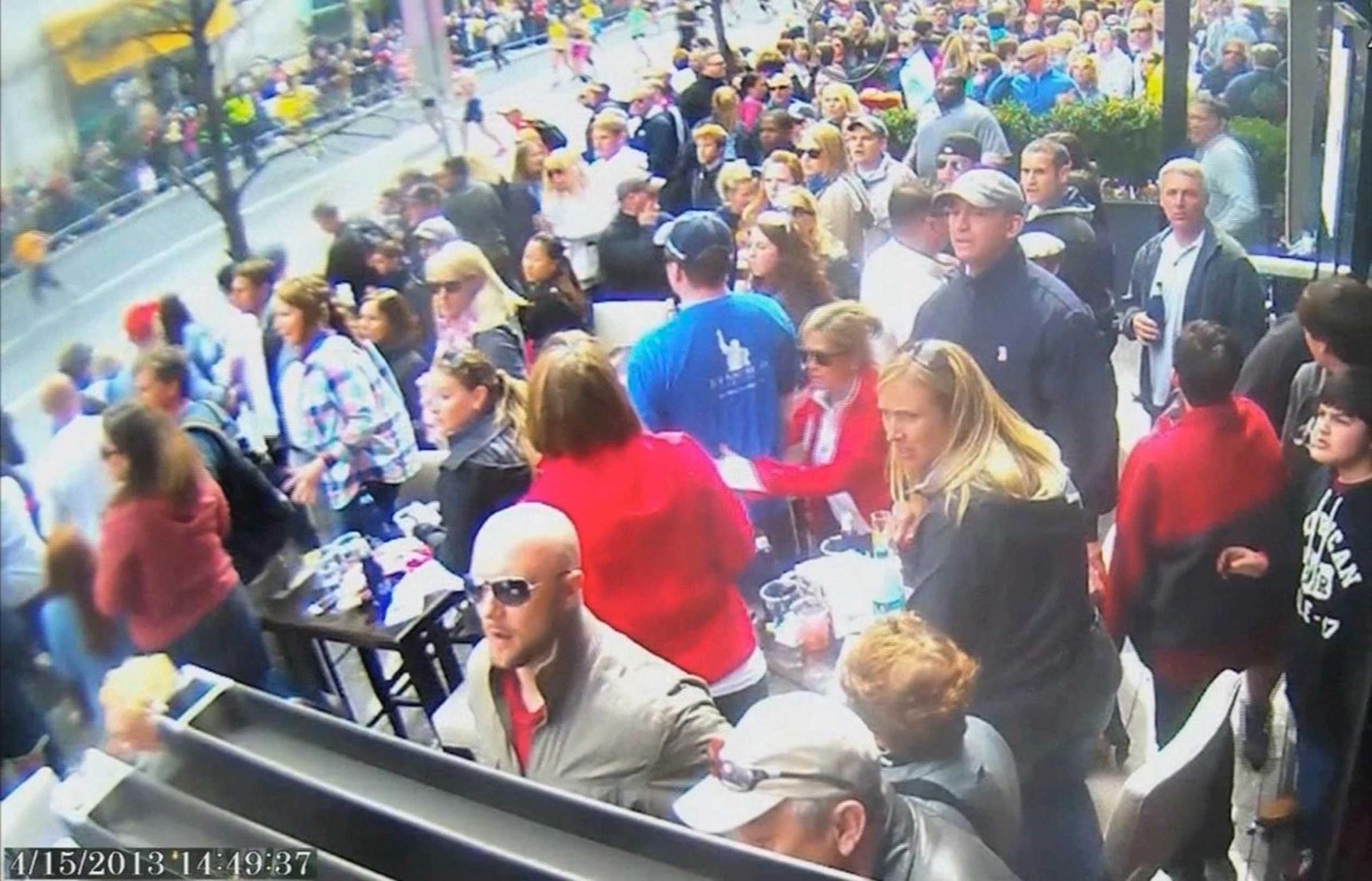

See Evidence From the Boston Bombing Trial

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Why Maternity Care Is Underpaid

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com