At 1:35 p.m. on Jan. 2, 2013, in a deserted, dusty shed in a clearing in what was once a lush, dense tropical forest a few miles southeast of the imposing ancient temple of Angkor Wat in northwest Cambodia, I had a rendezvous with history.

I found myself standing in front of a long-lost archaeological artifact whose importance for the history of science could not be overstated. It had taken me five years of intense effort to find this piece of stone. After talking to experts on three continents, and trekking through jungles, arid fields, sweltering deserts, and ragged mountains in India, Thailand, Laos, Vietnam, and Cambodia, I was finally here, in front of the object I had almost lost hope of ever finding.

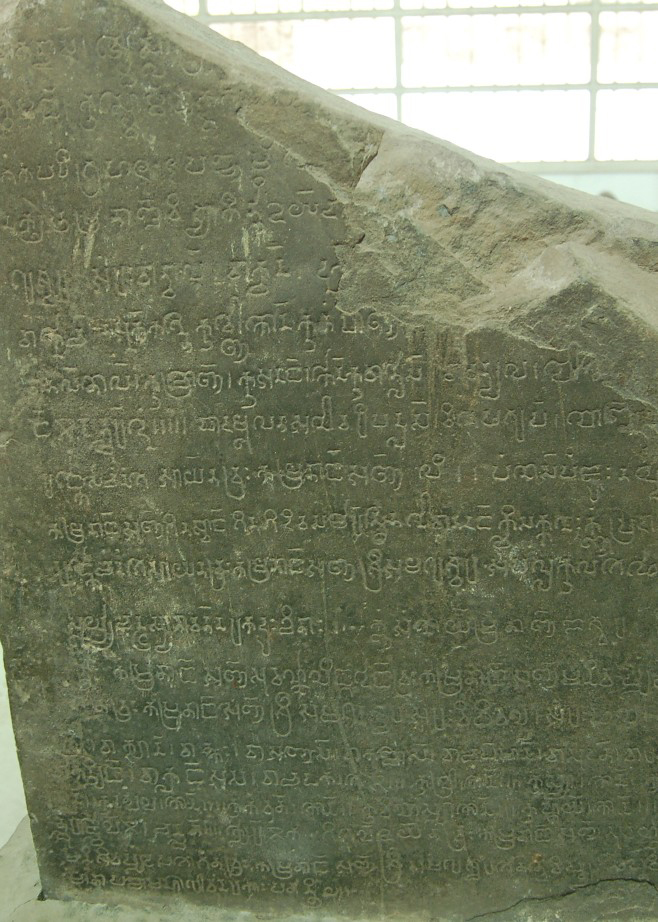

The artifact was a 5-foot-by-3-foot stone slab weighing half a ton, with ancient writings in a lost language chiseled into its smooth face. The language was Pre-Angkorian Old Khmer, an ancient form of the language of present-day Cambodia. This stele once adorned the wall of a 7th century temple at a place called Sambor on the Mekong River, all the way across the country, and it bore a description of the gifts made to this temple from the people of the area, including a list of slaves, five pairs of oxen, and white rice for the subsistence of those who worshipped there.

But what made it so important was its date. The inscription began: “The Çaka era entered year 605 on the fifth day of the waning moon.” It was this number, 605, that was so overwhelmingly important. Because we know that the Çaka dynasty began in AD 78, we can date the artifact exactly: to the year AD 683. This makes the “0” in “605” the oldest zero ever found of our base-10, “Hindu-Arabic” number system.

At least six centuries before, the Mayans of Mesoamerica had used a zero glyph in their calendrical calculations within a number system based on 18 and 20, and in the second millennium B.C. the Babylonians had employed a blank, and later another notational device, to mark a missing numeral within their base-60 number system (a relic of that ancient convention is how we measure time). But the Cambodian stone inscription bears the first known zero within the system that evolved into the numbers we use today. At this very early stage, it was represented by a wide dot rather than the familiar circle.

The zero inscription that I rediscovered in 2013 was first sighted in the Sambor temple in 1891 by Adhémar Leclère, a French colonial official. When the Cambodian National Museum was opened in 1920, it was taken and placed there on display. A French scholar named George Cœdès, who was a prolific translator of Old Khmer and Sanskrit inscriptions, studied this stele and published a groundbreaking article in which he used it to prove that the zero—the keystone to our number system—is of Asian origin, rather than European or Arab origin, as many scholars had believed at that time. Cœdès’s article established our entire understanding of the history of numbers.

For reasons that are still unclear, in 1969 the artifact was removed from the museum, and thereafter disappeared. In the mid-1970s, Cambodia came under the brutal rule of the Khmer Rouge, and over several years, Pol Pot’s henchmen tortured and murdered about 2 million people and destroyed much of Cambodia’s art and cultural heritage. It has been estimated that more than 10,000 ancient statues and archaeological artifacts were purposely smashed, and many others were looted and taken out of the country—their return now a matter of negotiation between governments. Therefore, few historians believed that the stele with the first zero still existed or could be found.

One of my first memories is of numbers. My father was the captain of a cruise ship that sailed throughout the Mediterranean, often calling at Monaco, and when I was very young, a ship’s steward would sneak me into the famous Casino de Monte Carlo. There I saw magical, ornate numbers on the roulette tables: half red and half black, and one special round circle of a number alone in green. Its image was etched in my mind, and in part led me to pursue a career in numbers as a mathematician and statistician. I became obsessed with wanting to find the origins of numbers, and when I first learned of the importance of the lost inscription from Sambor, I was determined to try to find it at all costs.

On March 27, 2015, Her Excellency Phoeurng Sackona, Cambodia’s Minister of Culture and Fine Arts, received me formally in her office in Phnom Penh and gave me the welcome news that, by her personal order, the inscription bearing the zero had now been transferred to the Cambodian National Museum, where it once was, and where it belongs. Everyone will be able to see this testimony to humanity’s great invention of the place-holding decimal zero: the ingenious device that allows us to represent numbers clearly and efficiently, and to distinguish, for example, between 12, 120, and 1002.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com