The U.S. oil production decline has begun.

It is not because of decreased rig count. It is because cash flow at current oil prices is too low to complete most wells being drilled.

The implications are profound. Production will decline by several hundred thousand barrels per day before the effect of reduced rig count is fully seen. Unless oil prices rebound above $75 or $85 per barrel, the rig count won’t matter because there will not be enough money to complete more wells than are being completed today.

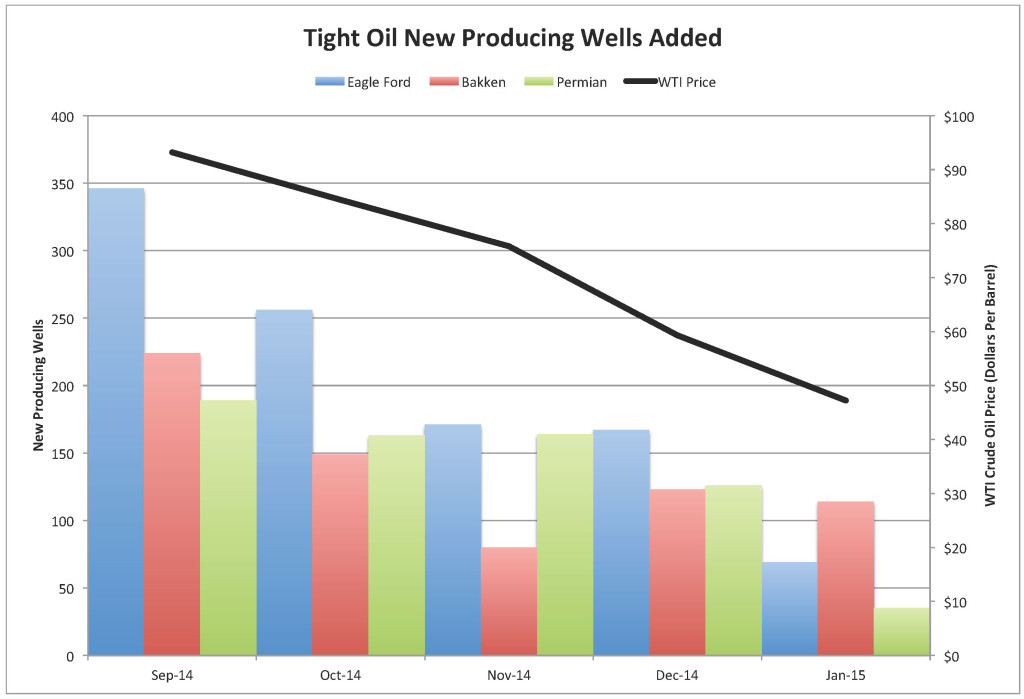

Tight oil production in the Eagle Ford, Bakken and Permian basin plays declined approximately 111,000 barrels of oil per day in January. These declines are part of a systematic decrease in the number of new producing wells added since oil prices fell below $90 per barrel in October 2014 (Figure 1).

Deferred completions (drilled uncompleted wells) are not discretionary for most companies. Producers entered into long-term rig contracts assuming at least $90 oil prices. Lower prices result in substantially reduced cash flows. Capital is only available to fulfill contractual drilling commitments, basic costs of doing business, and to complete the best wells that come closest to breaking even at present oil prices.

Much of the new capital from junk bonds and share offerings is being used to pay overhead and interest expense, and to pay down debt to avoid triggering loan covenant thresholds. Hedges help soften the blow of low oil prices for some companies but not enough to carry on business as usual when it comes to well completions.

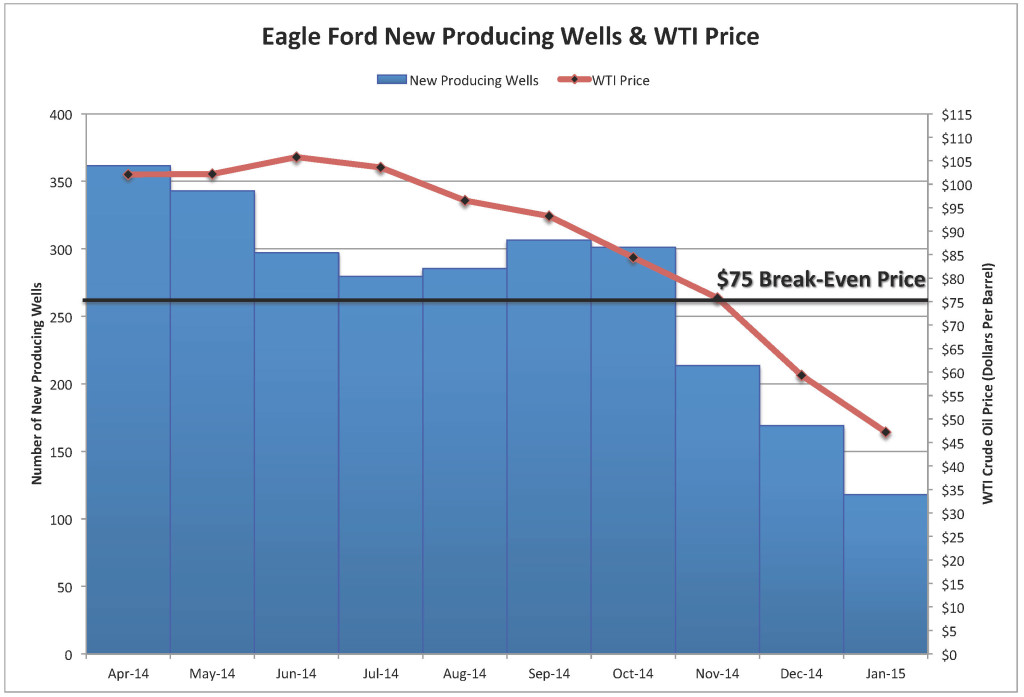

The decrease in well completions provides additional evidence that the true break-even price for tight oil plays is between $75 and $85 per barrel. The Eagle Ford Shale is the most attractive play with a break-even price of about $75 per barrel. Well completions averaged 312 per month from January through September 2014 when WTI averaged $100 per barrel (Figure 2). When oil prices dropped below $90 per barrel in October, November well completions fell to 214. As prices fell further, 169 new producing wells were added in December and only 118 in January.

Bakken break-even prices are higher at about $85 per barrel. Well completions averaged 189 per month from January through September 2014. In November, only 80 new producing wells were added. In December and January, 123 and 114 new wells were added, respectively. Orders for rail cars used to transport oil decreased by 70% in the first quarter of 2015 compared with the fourth quarter of 2014.

Permian “shale” play break-even prices are also about $85 per barrel based on declining well completion data. Well completions averaged 175 per month from January through September 2014. In January 2015, only 35 new producing wells were added.

Much of the commentary about the backlog of deferred completions is exaggerated and irrelevant unless oil prices increase to $75 or $85 per barrel. The assumption underlying most industry chatter these days is that oil prices will return to normal.

The world oil market is undergoing a fundamental structural change in response to expensive oil. Producers are trying to survive by limiting expenditures. While analysts have been focused on rig counts, deferred completions have emerged as the initial path to lower U.S. oil production. This unanticipated outcome suggests that others may follow. While everyone is waiting for higher oil prices and for things to return to normal, what we may be witnessing is the end of normal*.

*James Kenneth Galbraith, The End of Normal–The Great Crisis and the Future of Growth (2014).

This article originally appeared on Oilprice.com.

More from Oilprice.com:

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com