Bernie Sanders can kvetch like the great end-of-days preachers of old. When the white-haired senator stands behind the podium, he hunches, and punctuates his points with the tips of his fingers close together, as if grasping a jelly bean. He still has not lost his gravelly Brooklynese after decades in the backhills of Vermont. Income inequality, jobs, financial security—it’s all going to hell in a hand basket. To merely call Sanders a complainer, however, would ignore the urgency of his message: America really is in trouble.

“All of you know what’s going on in America today!” the Vermont senator said in a speech last week in Washington, D.C., where federal workers were rallying for better pay. “We have millions of working people living in poverty, and 99% of all new income is going to the top 1%. That is not what America is supposed to be about!”

The crowd surrounding him murmured its assent, and Sanders continued. “A great nation will not survive when so few have so much, and so many have so little!”

It is a prophecy that Sanders has been preaching for many years. Billionaires are buying our elections, too many Americans aren’t getting by, income inequality is becoming so extreme, and the country is reaching a breaking point.

Now, Sanders, the son of a Polish-Jewish paint salesman, a Brooklyn native and Vermont Senator, a former carpenter, filmmaker and writer, is running for president. Sanders confirmed his decision with the Associated Press on Wednesday, and by the end of May, he will officially kick off his campaign with an event in Burlington, Vt.

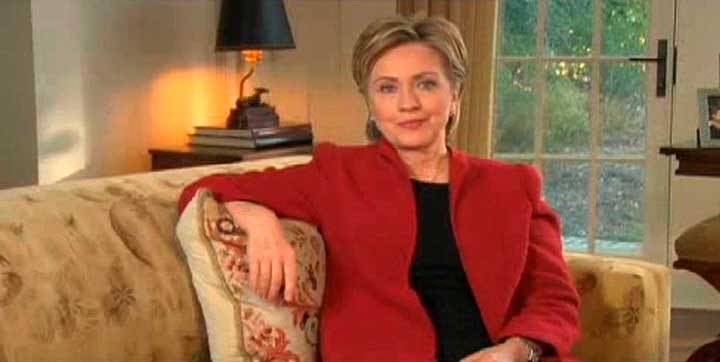

He is a blip in the polls, and he faces one of the strongest candidates ever to run in a primary, Hillary Clinton. But he has a deeply devoted following in Vermont, where he won his last reelection with 71% of the vote. He has friends in the primary states, and a grassroots fundraising operation. He’s a hardscrabble politician: he lost repeated races before getting elected mayor of Burlington in 1981. He represented Vermont for 16 years in the House and is midway through his second Senate term. He has a message that resonates, and he plans to run a serious campaign.

See 10 Presidential Campaign Launches

“People should not underestimate me,” Sanders told the AP on Wednesday night. “I’ve run outside of the two-party system, defeating Democrats and Republicans, taking on big-money candidates and, you know, I think the message that has resonated in Vermont is a message that can resonate all over this country.”

Sanders’ main problem is the only real one in politics: his electability. Sanders is the avowed contrarian of Washington. He’s a self-professed democratic socialist at a time when many Americans see the “S” word as the political equivalent of bed wetting. He’s one of just two Independents in Congress. (He will run for president as a Democrat.) He’s not afraid to compare the United States to other countries like Denmark and Norway. Born Jewish, he says he identifies with Pope Francis.

Read more: The Presidential Candidate Who Agrees the Most with Pope Francis

So naturally, in this time of polarization, Sanders has a devoted following. He’s made multiple trips in recent months to New Hampshire, Iowa, and other states around the country, and often attracted enthusiastic crowds. In recent polls in New Hampshire, he hovers above 10%. In late-April poll in Iowa, he got 14% of caucus-goers support. He attracts the discontented and the progressive.

“We had town hall meetings with Bernie Sanders,” said Hugh Espey, an Iowa-based activist who runs the Iowa Citizens for Community Improvement. “He got a great reception from everyday folks. Grandmas, grandpas, regular people. Fifteen hundred people came out to four town hall meetings. People are hungry for a fighter.”

The 2016 cycle will likely be the most expensive election in history by far. Hillary Clinton’s supporters and outside groups are seeking to raise well over $1 billion, and the Koch brothers plan to spend close to $900 million this election. For his part, Sanders won’t be waiting on wealthy donors in New York and Washington D.C. to write him checks, and there is no serious Bernie Sanders super PAC. Fundraising from millionaires, after all, is anathema to Sanders’ message.

To compensate, Sanders will rely on a not-so-secret money raiser: social media. Everybody’s doing it, but few will rely on it like the Vermont senator, whose team has a technological savvy that outpaces its political profile. With 291,000 Twitter followers and nearly 1,000,000 Facebook likes, he’s got a much bigger following than more powerful senators like minority leader Harry Reid, Mike Lee, and Elizabeth Warren. As any campaign handbook will tell you, social media outreach can seed small-dollar contributions and, eventually, votes.

If the social network lacks the firepower of multimillion-dollar donor network, or the closed-door fundraiser in Miami Beach, it has the potential to total many millions made up of $25 or $50 donations. That will complement the more than $4.5 million Sanders has on hand for his 2018 Senate reelection campaign, according to an FEC report, which he could use for a presidential race.

“We’re going to run a serious, credible campaign. It’s going to cost a lot of money,” said Tad Devine, who will be a top advisor to Sanders. (Devine held senior roles in the Al Gore and John Kerry presidential campaigns.)

“The front-end budget will be in the neighborhood of $50 million up and through the early states,” Devine said. “There will be a full-fledged campaign in some early states, and to gain access nationally and put the national campaign in scope, there’ll be costs.”

Sanders has earnest ideas, even if he hasn’t laid out all his policies in detail yet. He wants the United States to spend $1 trillion on infrastructure projects across the country, which Devine says could put more than one million people to work. He supports tighter regulations on Wall Street, opposes free-trade agreements like the Trans-Pacific Partnership and proposes raising taxes on the rich. He will fight climate change, and push back against money in politics.

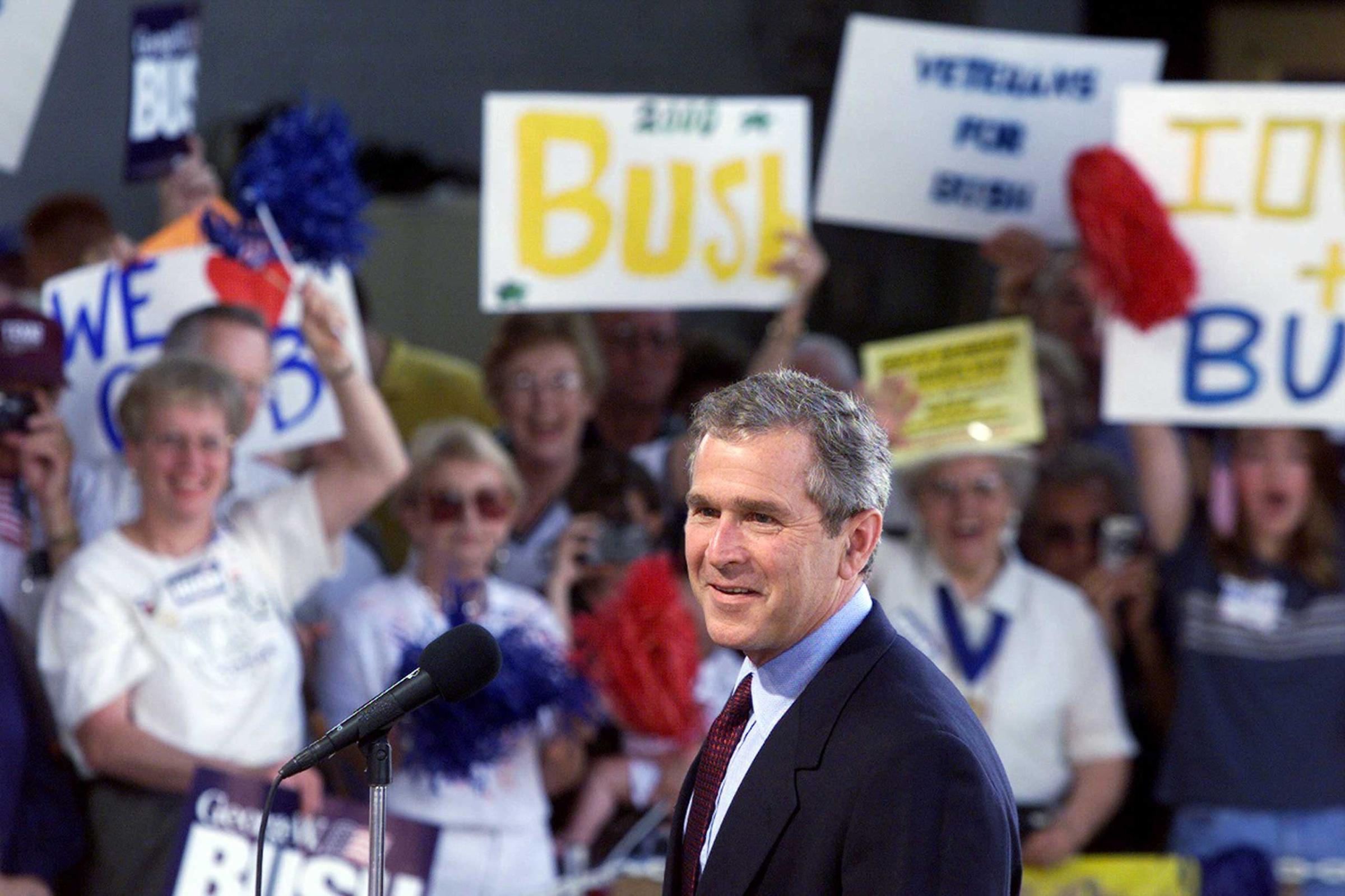

But Sanders biggest campaign theme could well be the campaign itself. It’s a meta-campaign—a campaign that is a message that is a campaign. In a note to his supporters, Sanders said early Thursday: “This campaign is not about Bernie Sanders. It about a grassroots movement of Americans standing up and saying: ‘Enough is enough. This country and our government belong to all of us, not just a handful of billionaires.’” It’s a campaign about populism, about running against giants like Hillary Clinton and Jeb Bush, and about underdogs—be they working families or presidential candidates.

The question is whether voters outside his home state will be able to picture him in the White House. In that way, his campaign is about to be like a piece of spaghetti, thrown at the wall.

“We have to see whether this translates into a powerful message, and into the more prescribed contours of a presidential campaign,” said Devine. “Not just union halls, town hall meetings and auditoriums, which he’s been using as sounding board. We have to see whether he gets in with real voters. Whether this moves them.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com