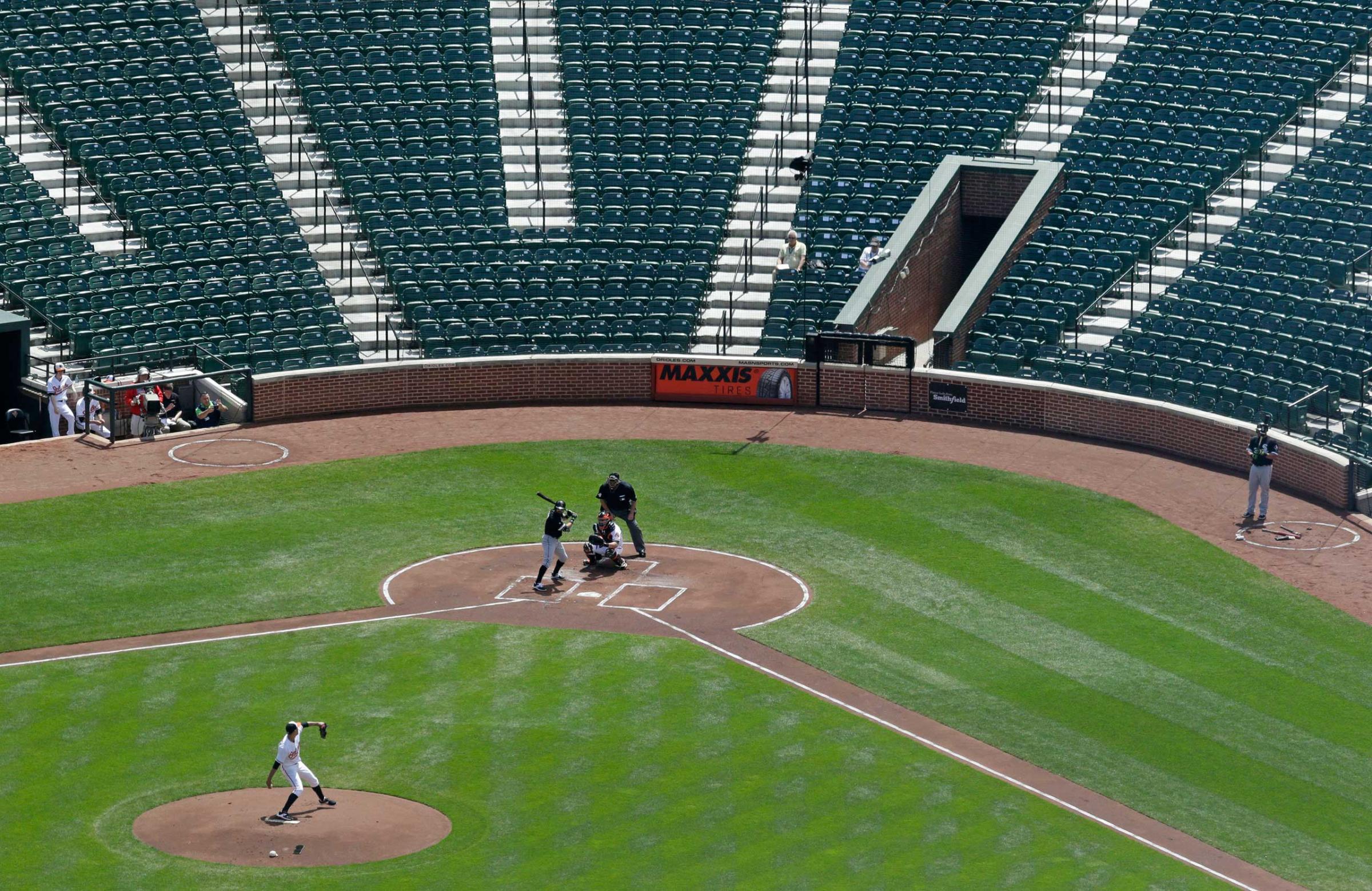

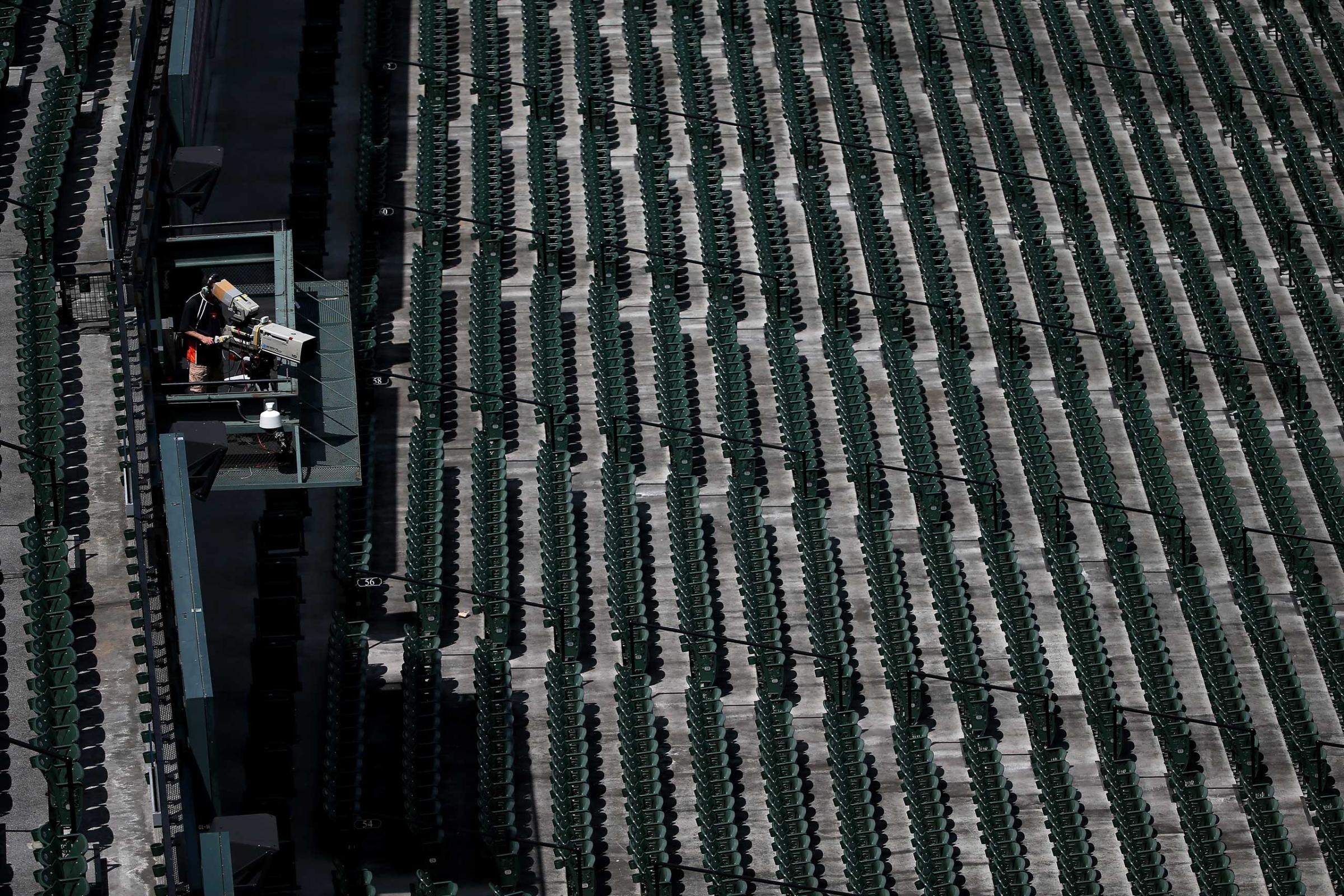

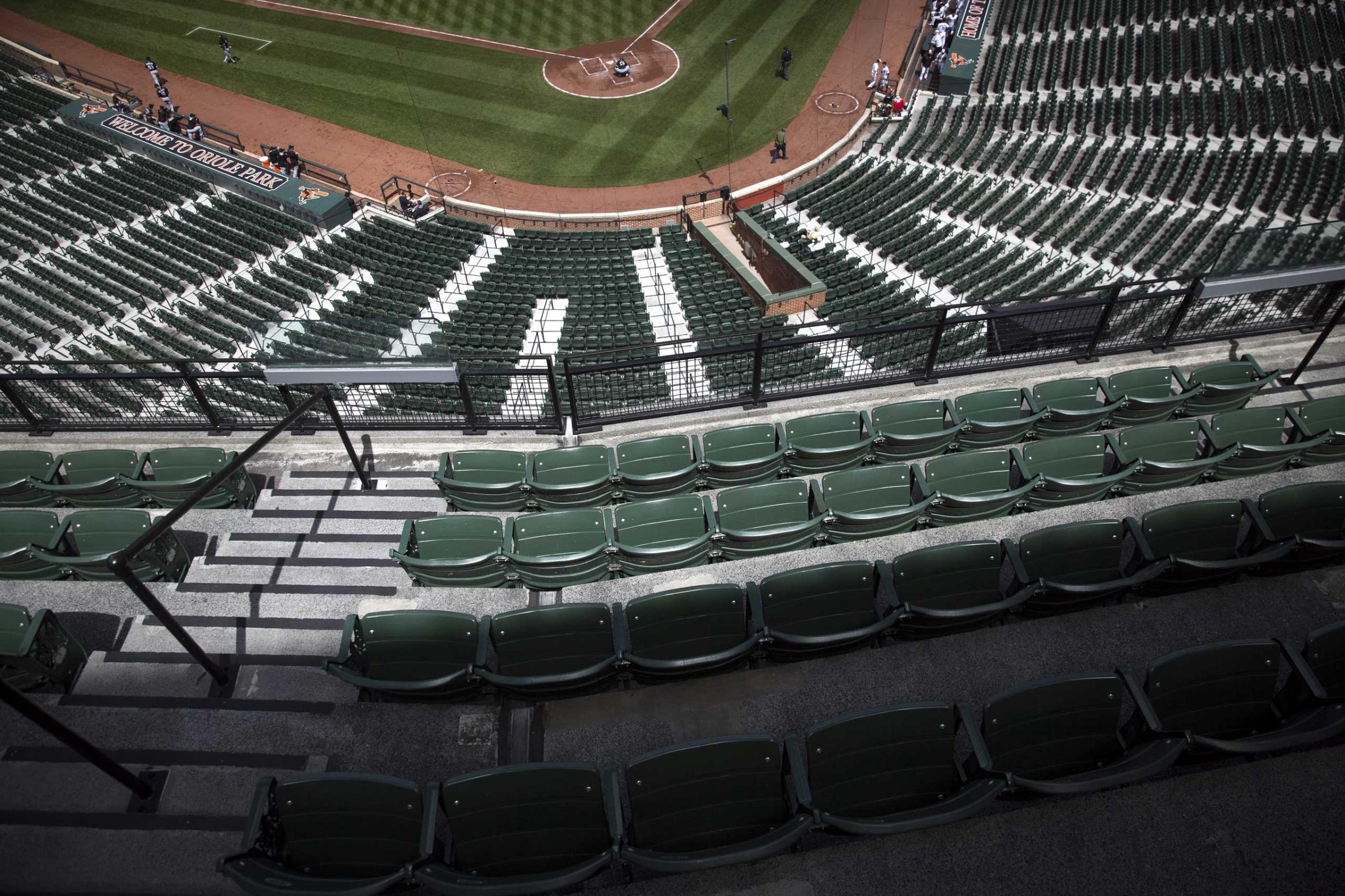

Ah, the sounds of Baltimore Orioles baseball, on a day where there were no fannies in the seats. Pop, echoing throughout the empty stadium, when the ball hit the catcher’s mitt. Thwack, bat on ball, especially during Baltimore’s first inning, when the Orioles took a 6-0 over the Chicago White Sox. (Silent sluggers, these guys). And plunk, as foul balls bounced off the seats with no fans. (Who’s on foul ball cleanup duty?)

This eerie game—official paid attendance, zero—went off as advertised on Wednesday, and it was as surreal as everyone expected. As a public safety caution in the wake of the violence that erupted Monday—following the April 19 death of a 25-year-old black man, Freddie Gray, who sustained a fatal injury while in police custody—the Orioles decided to keep fans out of Camden Yards. (Protests, mostly peaceful, continued into Wednesday evening. Hundreds walked through the streets, and a crowd was present at City Hall.)

Still, the national anthem played, a public address announcer spoke to a few members of the public, and the organ hit the notes of “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” during the seventh inning stretch. John Denver’s “Thank God I’m A Country Boy” also blared over the loudspeaker. Outside the home plate entrance, a security guard acknowledged this was the easiest gig she’s ever had, as only a few media members strolled by.

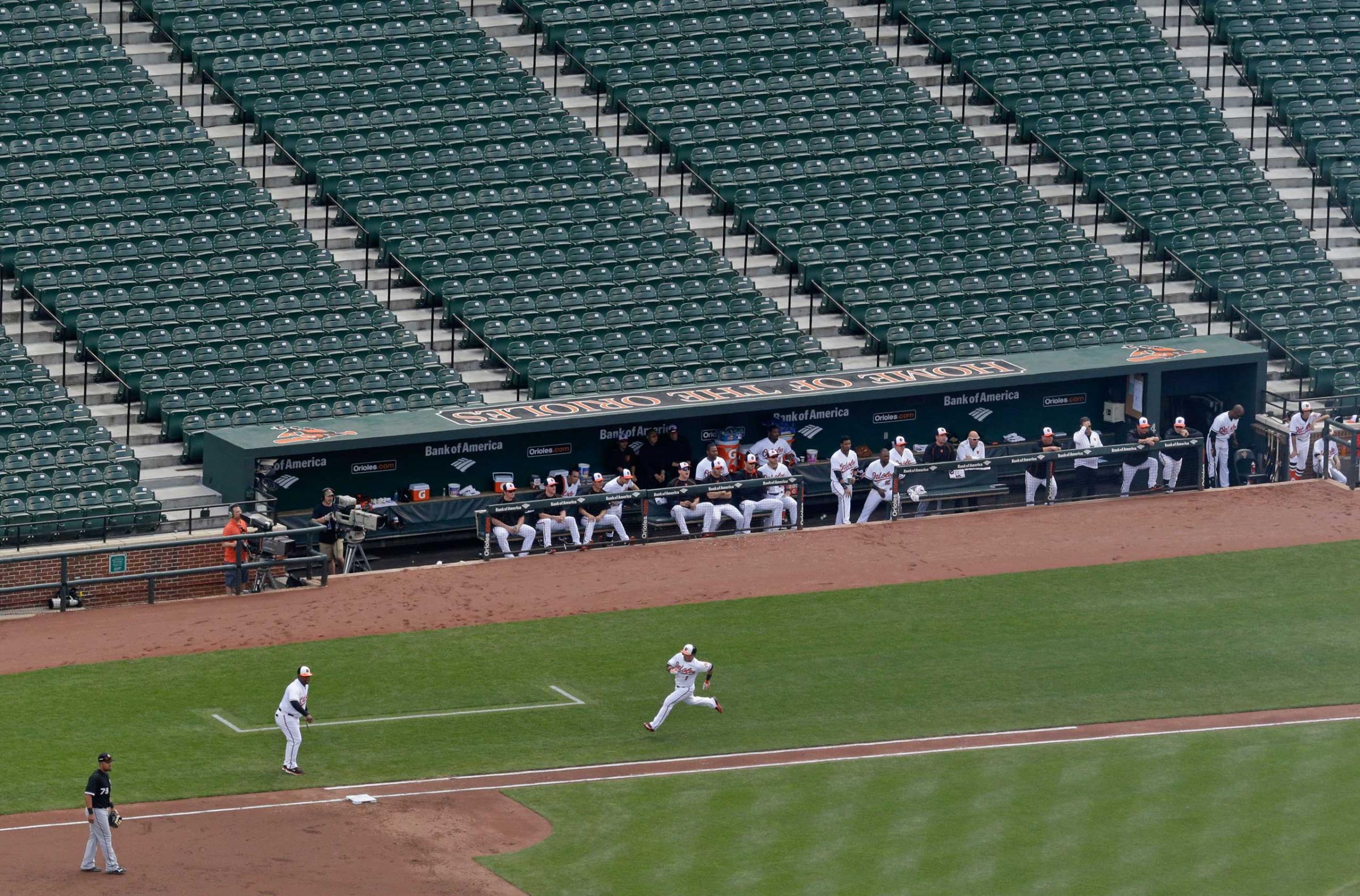

Baltimore won, 8-2, in brisk two hours and three minutes, to the delight of the players. “If you want to talk about the pace of play, we might have found a solution,” Baltimore pitcher Tommy Hunter joked in the locker room afterwards. “We might have found something today.”

For businesses around Camden Yards, the day wasn’t as blissful. “Look around,” says Mandy Goddard, a bartender at Pickles Pub, across the street from the ballpark. “It’s all news reporters. There are two actual customers.” A manager for the pub says business is down 90% from a regular game. The postponement of two Orioles games earlier this week, the empty game today and the move of a three-game home series—starting May 1—to Tampa is costing Goddard. She estimates that she makes $100 to $400 on game days. “In my tip bucket right now, there’s $8,” Goddard says. She doesn’t like the team’s approach to this week’s games, though she says she understands why the Orioles are being so cautious, given the flare-ups near a game last Saturday night.

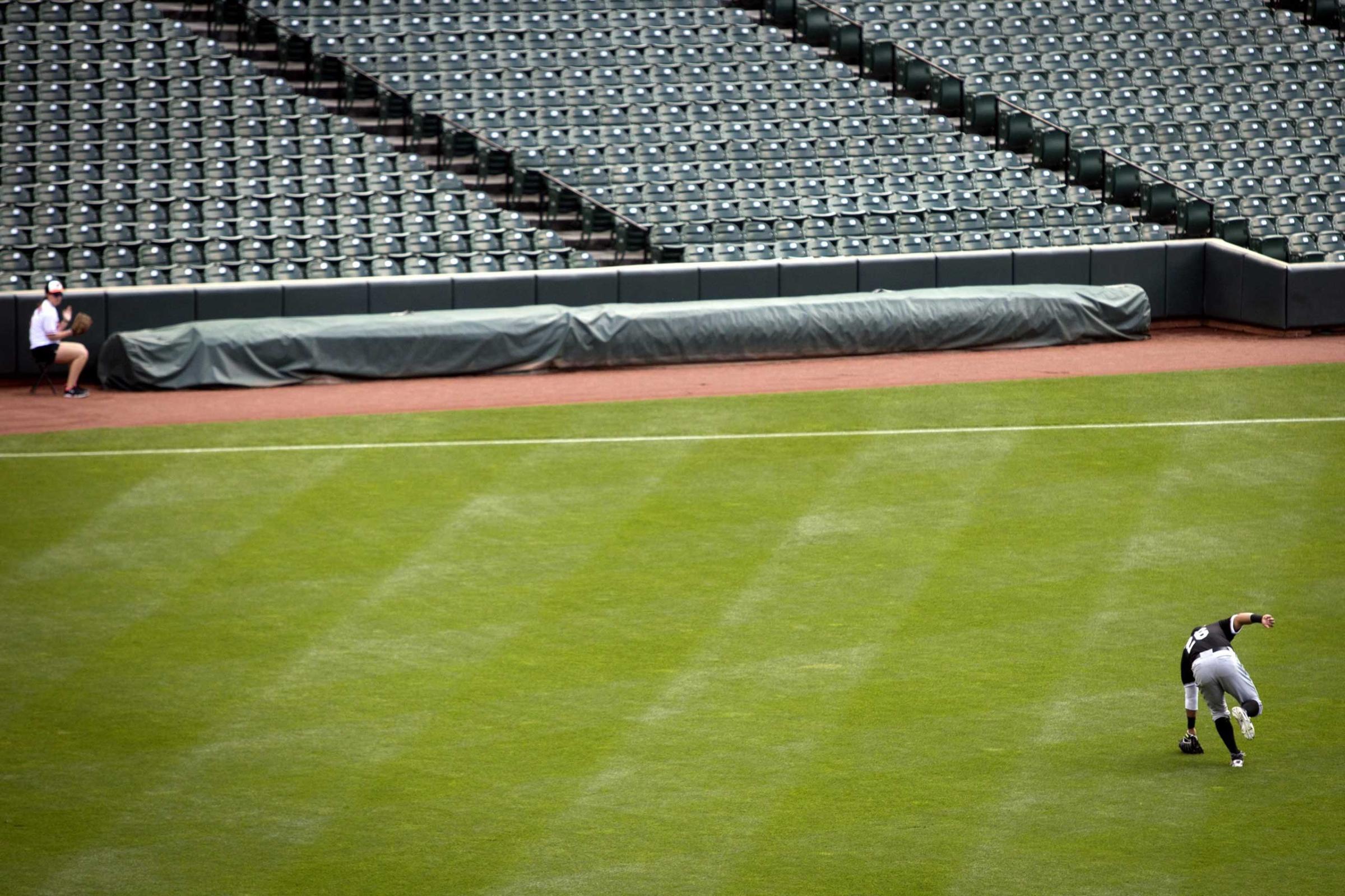

As first pitch approached, and a few players stretched on the field, the speakers played the cheesy 80s song “Party All The Time.” Right before the first pitch, one of the few dozen fans who gathered behind a left center field gate, and on Hilton balconies overlooking the ballpark, yelled, “Hey, good luck,” for everyone to hear. Orioles first baseman Chris Davis called the silence “deafening,” though he got plenty used to it, as he smacked a long three-run home run to right in the bottom of the first. The ball landed on Eutaw Street, in front of the famous B&O Warehouse, just the 80th shot to travel such a long distance since the ballpark opened in 1992. Davis said the small signs of normalcy—the public address system and a batter’s individualized walkup music, sprinkles of crowd noise from beyond the gates—at least offered the veneer of a routine. Davis even stuck to his tradition of tossing balls into the stands after an inning, even though no invisible hands were there to catch them. “It’s just reaction, I thought it would be fun,” Davis says. “I gave some love to the fans in the upper deck.”

The spectators with actual flesh, outside the stadium, were able to see the obstructed action, and offer an occasional, and very audible, “Let’s Go Orioles” chant. Chris Petro, a sound engineer at a local rock club, decided to rent out room 567 at the Hilton, whose balcony offered at least a partial view of the action. He expected around 15 friends to rotate in and out during the day. One of them was a local funeral director, done for the day, who was drinking National Bohemian—”Natty Boh”—a beer with local roots. “Why not throw a party, with booze, beer and my dog?” says Petro, whose black lab, Sara Sue, lay on the living room floor. “It’s nothing without her.” The bill came to $260 for the room—plus an extra $50 for Sara Sue.

In the fifth inning, the few dozen fans had something more to cheer about. Manny Machado hit another Orioles home run, giving Baltimore an 8-2 lead. The crowd standing against the fence in left center couldn’t see the ball clear the wall, so they looked for clues. Here, they saw Machado’s start to trot, then raised their arms and yelled. The delayed reaction—no noise after a ball goes over a wall—freaked Machado out a bit. “It’s a weird feeling, running around the bases and no hearing anything,” he says. “That’s crazy, something that never happens. Never happens. It’s something I’ll never forget.”

Hopefully, the quirks of this game won’t have to be repeated. The serious circumstances lingered. On the room 567 balcony, the mood turned serious when bartender Crystal Dunn reflected on the impact of the violent protests and citywide curfews. “It’s hurting everyone,” Dunn says. “And tourists are going to to afraid to come here. It’s going to have a rippling effect.”

During a news conference after the game, a young man who said he lived in a Baltimore neighborhood where tensions are high addressed Baltimore manager Buck Showalter. He asked Showalter his advice for the city’s young black people. “You hear people try to weigh in on things that they don’t really know anything about,” Showalter said. “I’ve never been black, OK? So I don’t know, I can’t put myself there … It’s a pet peeve of mine when somebody says, ‘Well, I know what they’re feeling. Why don’t they do this? Why doesn’t somebody do that?’ You have never been black, OK, so slow down a little bit.” (Read Showalter’s full response here)

One fan standing in left center, Brendan Hurson, a federal public defender, carried a sign that read “Don’t Forget Freddie Gray,” with the o’s styled like the team’s logo. He disagrees with the team’s decision to play the game with no fans. “It shows fear, and it’s divisive,” Hurson says. To him, keeping fans out symbolized the current state of Baltimore. “So many young people are locked out of the life they want to lead,” Hurson says. “This is such a stark reminder.”

Read next: How Baltimore Police Lost Control in 90 Minutes

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Sean Gregory / Baltimore at sean.gregory@time.com