This post is in partnership with History Today. The article below was originally published at HistoryToday.com.

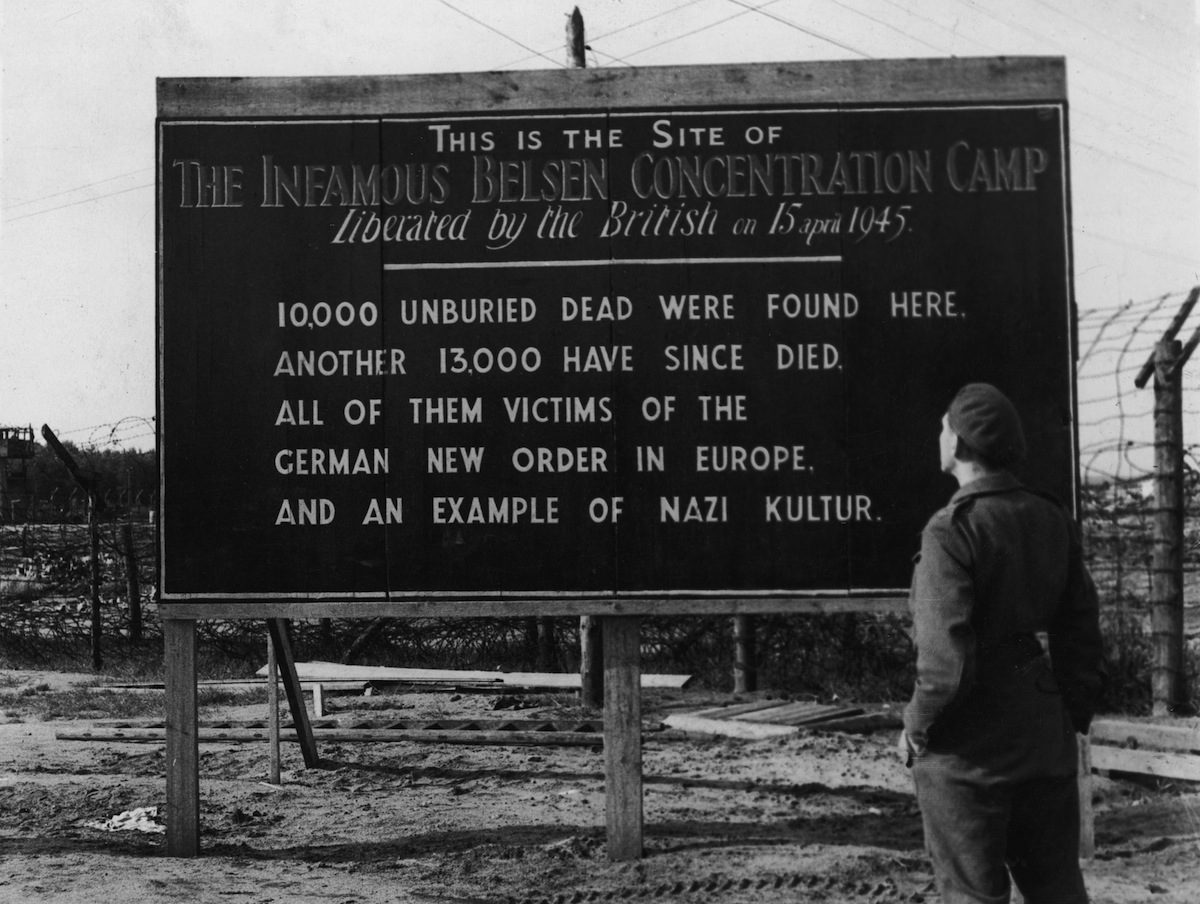

At the Imperial War Museum in London, academics and survivors assemble on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of the liberation of 60,000 inmates and the discovery of 13,000 corpses at the Bergen-Belsen concentration camp in Lower Saxony in 1945. The anniversary is marked, too, by a proliferation of articles online discussing the anniversary and its place in the British collective memory. ‘In British memory’, writes Rainer Schulze,

‘Belsen has become an imagined site, largely disconnected from the real place Bergen-Belsen. There’s no doubt that this imagined site still exists in the British memory landscape, ready to be brought to the fore when it becomes useful.’

That the names of the Nazi concentration camps should have a semantic weight extending far beyond a geographical location is clear. As the literary critic James Wood has pointed out, the novelist WG Sebald evoked the constant presence of perhaps the most famous camp of all without even writing its name in his 2001 novel Austerlitz. Since its liberation on 15th April, 1945, Belsen has been subject to direct and indirect representation. William Golding considered his most famous novel, Lord of the Flies (1954), a Belsen parable in the same vein as George Orwell’s Animal Farm. The Nigerian poet Chinua Achebe used Belsen symbolically (if not accurately) in his poem ‘Vultures‘; both works have appeared on the school syllabus in England and Wales.

Belsen, much of the current discourse seems to hold, occupies an elevated place in British collective memory because of its perceived ‘Britishness’. It was the first Nazi camp to be liberated, by the British 11th Armoured Division in 1945, and provided the public with the first visual evidence of Nazi war crimes, images not easily forgotten. At the Imperial War Museum’s seminar (the third to be held since Belsen’s liberation; the last was in 1995) new academic perspectives on Belsen are delivered to a room that includes survivors and their relatives. Dan Stone, author of The Liberation of the Camps (Yale University Press, 2015) suggests that, since the 1990s, there has been a generally held assumption that British collective memory has ‘got Belsen wrong’; that the British public has misunderstood Belsen’s place within the camp system. Belsen was not a ‘death camp’; pre-1944 it was primarily an exchange camp, where prominent Jews were held for exchange with German prisoners of war; it only became a death camp in the final few weeks, after the Soviet offensive in the East prompted the ‘death marches’ west, one of which was described by Elie Wiesel in his memoir Night. Yet, argues Stone, the case against ‘Belsen as a death camp’ is reliant upon top down history. From the perspective of the perpetrators, Belsen was embedded in a strategic system and identified as holding a specific purpose; from the perspective of the victims who arrived after 1944 it was ‘just another camp’. Distinctions between types of camp – faced with the notorious overcrowding and neglect at Belsen – would have proved impossible. ‘Scholarly precision’, says Stone, can ‘mask the true experience of the Holocaust’.

Scholarly precision is one obstacle; absence of testimony is another. Anna Hajkova speaks about the absence of testimonies by Jews who happened to be gay. Homophobia, she says, is rife in testimonies recorded by survivors as late as the 1980s and 1990s. ‘Prejudice determines what is in the archives – but thinking about the gaps can help’. The Imperial War Museum has no shortage of documentary material from the camp’s British liberators; yet the Holocaust is missing a queer history. Such a thing, of course, is near impossible to recover; Hajkova makes a compelling case for identifying the gaps, drawing attention to where they fall and listening to their silence.

In her talk on Soldier’s Perspectives, Myfanwy Lloyd presents testimonies recorded by members of the Oxfordshire Yeomanry which foreground the effect of the camp’s discovery on the liberating soldiers. One account, by Ronald Payne, describes how there was ‘very little chatter’ among the British soldiers after Belsen’s liberation, a detail that calls to mind an anecdote relayed by WG Sebald in his 1995 novel The Rings of Saturn (subtitled, in the original German, ‘An English Pilgrimage’). Discussing representations of Belsen at the seminar, Robert Eaglestone highlights Sebald’s work as an example of what he considers the ‘third phase’ of the camp’s literary representations in which literature shows both an educated awareness and a direct approach when dealing with the subject (missing from the symbolic works produced by Golding, Achebe and others in the 1950s, 60s and 70s). Sebald’s narrator (often considered to be the author himself) recalls reading an article from the Eastern Daily Press on the death, at 77, of a Major George Wyndham Le Strange, who served in the anti-tank regiment that liberated Belsen in April 1945. Sebald includes the clipping, and a photographic image of bodies scattered among trees in the liberated camp, within the text. The clipping, titled ‘Housekeeper Rewarded For Strange Dinners’ relays a story told by Mrs. Florence Barnes that she was employed by Le Strange in 1955 as his housekeeper and cook, on the condition that she dine with him every day ‘in complete silence’. On his death, Le Strange left his estate, worth several million pounds, to his silent housekeeper.

If Sebald’s work does indeed belong to a developed, direct and educated sphere of literary responses to Belsen, as Eaglestone suggests, it’s worth considering its place within the novel. To Sebald’s narrator Belsen is a collective memory, and a simple walk around the Sussex coast is enough to trigger it. It appears in the text overtly and factually but its meaning, or symbolic literary value is ambiguous and unclear: ‘To this day I do not know what to make of such stories’, he concludes.

Belsen: Seventy Years On was held at Imperial War Museum in partnership with Royal Holloway University of London, the University of Sheffield and the University of Warwick.

Rhys Griffiths is editorial assistant at History Today.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com