A citywide curfew that went into effect late Tuesday until early Wednesday brought calm to Baltimore in the wake of riots that spotlighted deep tension between police and the community and drew parallels to the unrest of 1968. But now that the city is picking up the pieces, thanks in part to thousands of National Guardsmen and law enforcement officers who will enforce the curfew for several more nights, the question for Baltimore officials and residents is how to prevent all this from happening again.

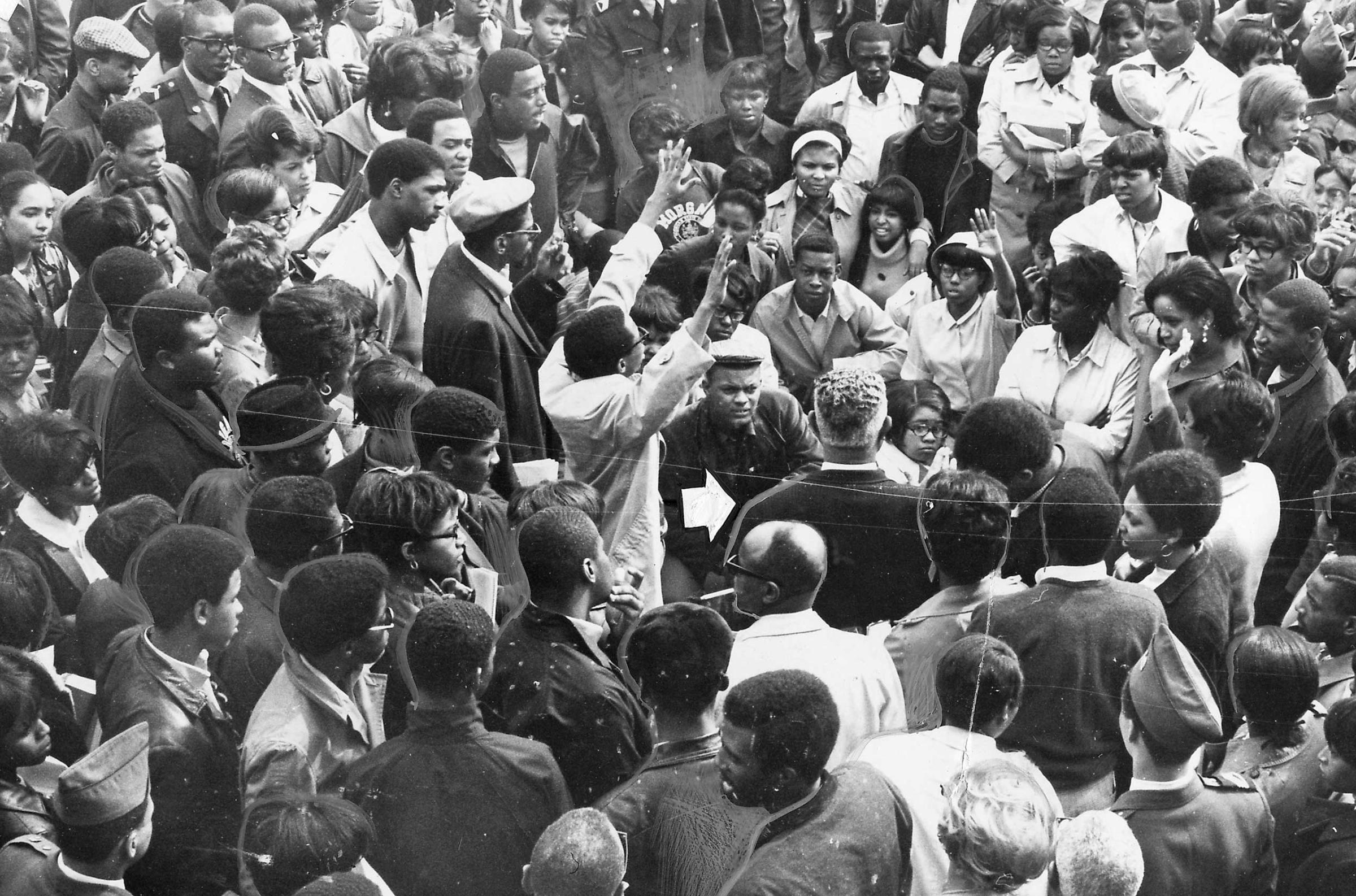

Protesters in Baltimore marched for several hours ahead of Wednesday night’s curfew at 10 p.m., at which time lines of law enforcement officers and others in armored vehicles set out to keep the streets clear until 5 a.m. Elsewhere, in New York City and Washington, D.C., large groups of demonstrators amassed in shows of support for Baltimore and against police brutality.

Monday’s violence arose from rising tensions following the April 19 death of Freddie Gray, 25, who suffered a severe spinal injury after a confrontation with police a week earlier. Gray’s death became the latest instance of a black man’s death at the hands of a law enforcement officer reigniting the national conversation about race and police force, just as other incidents in South Carolina, Ferguson and New York City, among others, had done since last summer.

To avoid widespread protests and incidents like what occurred with Gray, experts say Baltimore will likely need to address several long-standing issues: the patterns of segregation that still exist throughout the city; the lack of opportunity in predominantly black neighborhoods; and the long-standing mistrust between police and minorities.

Baltimore has a history and pattern of racial segregation that began more than a century ago, and its shadows still linger. In 1910, the city adopted a policy mandating that black residents couldn’t live on a block where more than half the residents were white. While the policy was later struck down as unconstitutional, Baltimore remains starkly divided along similar racial lines that originate from those socioeconomic boundaries.

Gray was arrested in one of the poorest neighborhoods, Sandtown-Winchester. A fifth of its residents are unemployed and a third of its homes sit vacant. It has about twice as many liquor stores as the city average, according to a 2011 report by the Baltimore City Health Department, and 25% of juveniles living there were arrested between 2005 and 2009.

“It’s one of the most disinvested neighborhoods in our city,” says Lawrence Brown, a community activist and professor of health policy at Morgan State University.

See Protests Against Police Violence Across the U.S. After Freddie Gray's Death

Baltimore’s Inner Harbor, meanwhile, is bustling with shops and tourist attractions. Seema Iyer, a University of Baltimore economics professor, says the areas around the Inner Harbor grew by about 15% to 20% between 2000 and 2010. Still, it is predominantly white.

Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake has focused on lowering the property tax rate to lure homeowners into the city while also implementing a tax on soda bottles to help fund reinvestment of public schools. It’s all part of her goal to bring 10,000 families new families into Baltimore by 2020.

“You have to have a broader tax base to have a sustainable city,” says Bill Cole, president of the Baltimore Development Corporation.

But the problem is that most people moving to the city aren’t looking to relocate into neighborhoods that could benefit the most from new businesses setting up or families moving in.

“There’s still gross underdevelopment where Mr. Gray is from,” says Jamal Bryant, pastor of the Empowerment Temple AME Church in Baltimore. “Rome isn’t built in a day, but we at least want to get to Venice to see some levels of progress in these urban centers.”

The city has instituted a program called Vacants to Value in which the city buys up properties, refurbishes them and attempts to resell them. There are 16,000 vacant home within Baltimore; city officials acknowledge they have demolished or rehabilitated 3,000 so far, but experts say many residents don’t want to live in those properties even if they’re refurbished.

“The unfortunate thing is there is no demand for them,” says Barbara Samuels, a lawyer for the ACLU of Maryland, who has worked on housing issues. Samuels says the city should provide more opportunities for people to leave those neighborhoods and “go to an area that’s not racially or economically segregated.”

Baltimore’s population, which steadily declined for decades, appears to have stabilized in recent years, settling in at around 600,000. But the poorest neighborhoods have remained stagnant, or even declined.

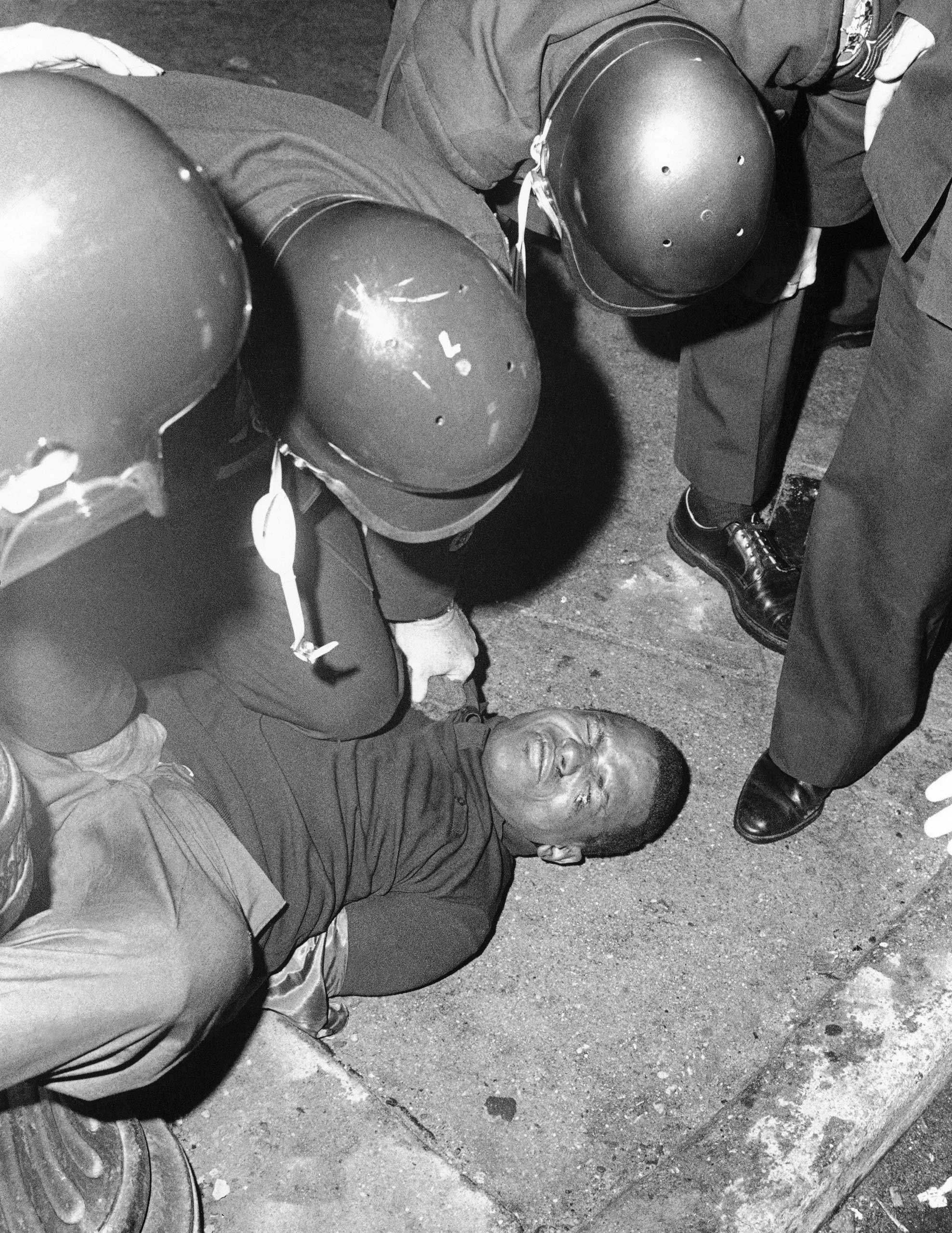

Those patterns of segregation and a divide between haves and have-nots have led to years of animosity between residents and police. Last year, the Baltimore Sun reported the city had paid out almost $6 million between 2011 and 2014 to residents, many of them black, that police officers had abused. The city has paid out $45 million for “rough rides” in police vans, like what many believe occurred with Gray, following two incidents in which those arrested were paralyzed.

Another problem may stem from the fact that only a quarter of Baltimore police actually live in the city, one of the lowest rates in the country, according to Census data analyzed by FiveThirtyEight. The rest live either in Baltimore County or out of the state, and that can have an unintended effect on how police do their jobs. Some local activists are pushing for the police department to recruit more officers from within the city, believing it could change how local residents interact with the officers patrolling their neighborhoods” on the police from out of town

“Police used to know everything on the block. The people who did hair, the people who had the best gossip,” says Cortley Witherspoon, a Baltimore religious leader and social activist. “But now, people are coming in with culture shock. We need to make sure officers come from the city that they are patrolling.”

City Council President Jack Young says he believes that each officer for the first two years on the job should reside in Baltimore. “They should live in the city,” he adds, simply.

One change that could potentially help Baltimore heal is if residents start to feel that police are being held accountable for their actions.

“You have to have justice where people who have committed these kinds of acts are fired,” says Brown, of Morgan State. “The city is settling time and time again instead of punishing these officers. There is a history of violence in this police department, but they’re never held accountable.”

The city’s first test on that count will come Friday, when police will turn over its investigation into Gray’s death to the state’s attorney general. A second test could come the next day, when a rally is expected to draw thousands of people back into the streets.

Baltimore Protests, Then and Now

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com