In early 1972, Stanley Cloud, who was then TIME’s bureau chief in Saigon, wrote a short piece for the company’s internal newsletter, F.Y.I. The piece—headlined “Right, An”—was a profile of a man named Pham Xuam An, who had been working for TIME in Vietnam since 1966 and had been officially hired to the magazine’s staff in 1969. He was the first Vietnamese person to become a full-fledged staff member for a major American news outlet covering the war.

“Perhaps it is letting the cat out of the bag, but I suppose that it is safe to say that Pham Xuan An has been no less than the secret weapon of a long line of correspondents who have traipsed in and out of Saigon—the incumbent crew conspicuously included,” Cloud wrote. “Although he rarely files himself, his dogged research and legwork, his remarkable knowledge and background, play an important part in virtually every file produced by a staff correspondent.”

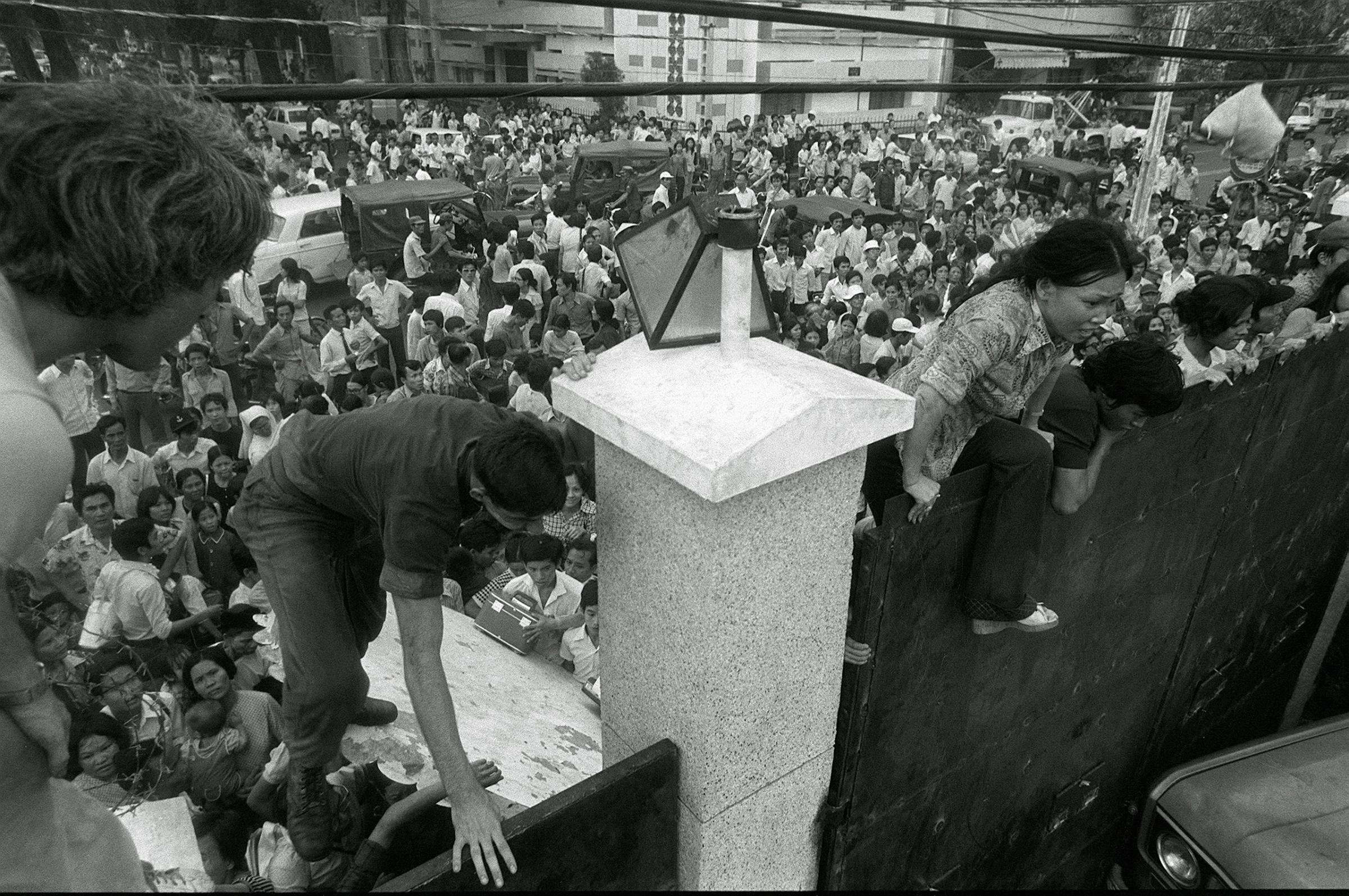

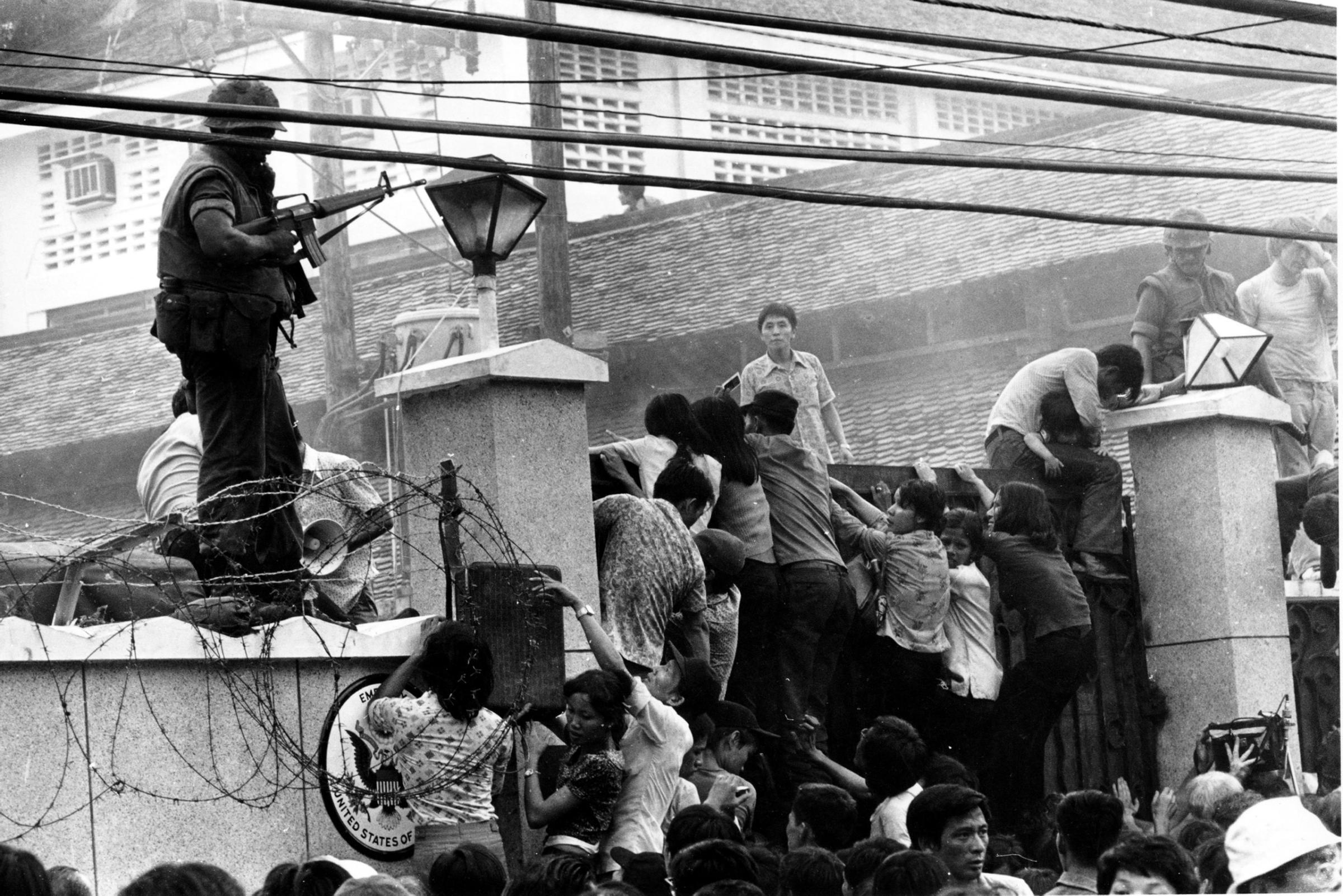

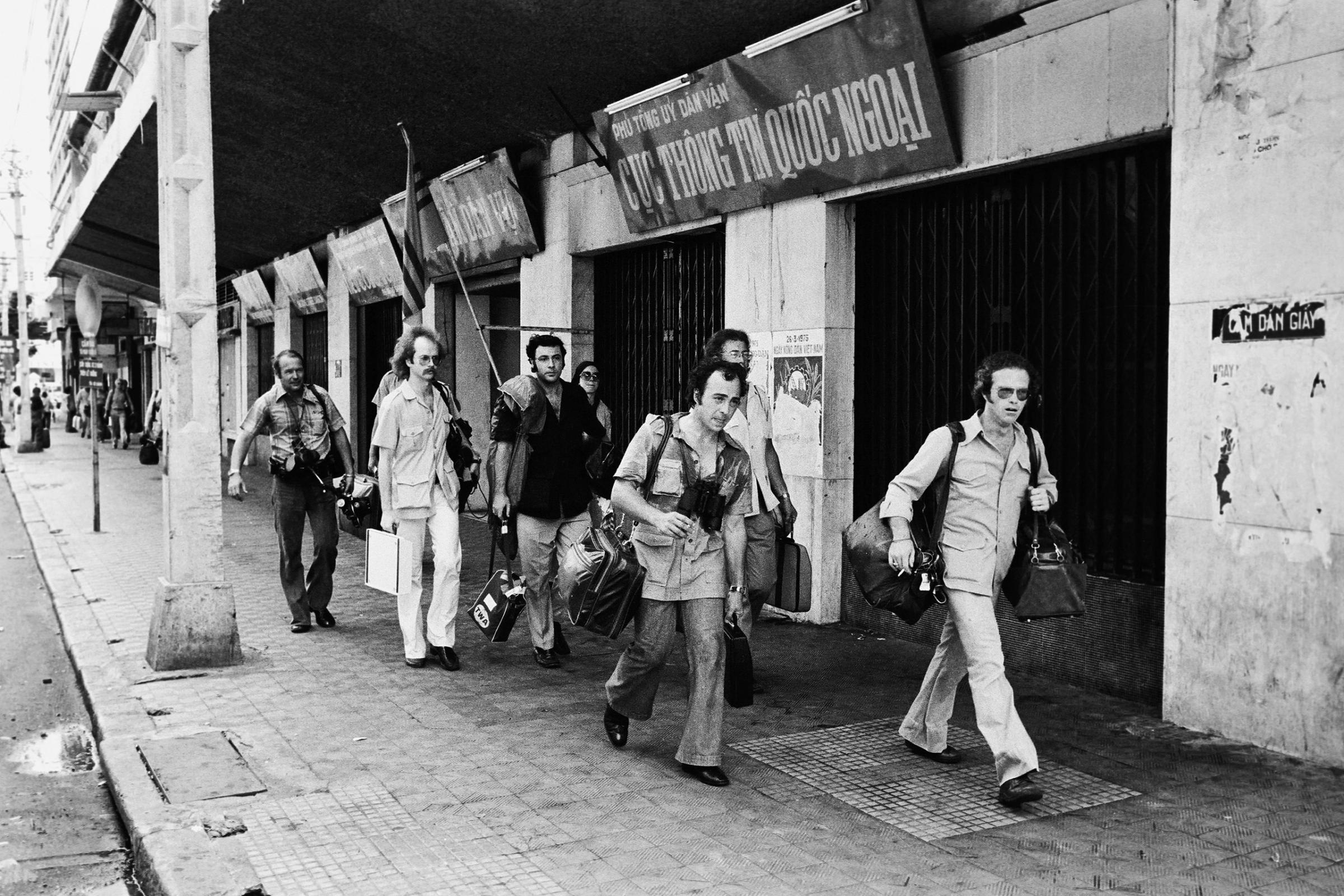

An continued to work for TIME through the end of the war. When TIME’s staff was evacuated before the April 30, 1975, fall of Saigon, he was the one who stayed behind. An issue of F.Y.I. from that May noted that, a few hours after the evacuation was complete, the following message came over the Telex machine: “Here is Pham Xuan An now. All American correspondents evacuated because of emergency. The office of TIME is now manned by Pham Xuan An.” Years later, in 2006, when An died at 79, Cloud memorialized him as a first-class journalist with an easy laugh.

Cloud wasn’t the only one who was fond of An. “He was an intellectual, dog-lover, bird-lover, chain-smoker, super smart guy, and we thought a great reporter,” says Peter Ross Range, 73, who was TIME’s Saigon Bureau Chief in 1975. “But An was also a little strange. He would disappear for days at a time and nobody had any idea where he was. Now of course we know where he was at least part of that time.”

An, it turned out, had been more than a journalist.

Before, during and after working for TIME, he was an intelligence officer for the Communist North Vietnam. The dogged research he conducted for his magazine American employers also went to the group the United States was fighting against.

That’s not the whole surprise, either. What’s perhaps just as striking in the story of Pham Xuan An is the good will his former colleagues still feel toward him.

His story was a complicated one: An began his association with the Viet Minh in the 1940s. Though he did intelligence work for both the South Vietnamese Army and the Central Intelligence Agency, he continued his allegiance to that anti-occupation group the whole time. He studied journalism in the United States in the 1950s and was an intern at the Sacramento Bee before returning to Vietnam, where he began to work for American outlets almost immediately. “Journalism is a splendid cover for a spy,” notes Thomas Bass, author of 2009’s The Spy Who Loved Us, a book about An.

Though his four children and wife evacuated to the United States at the end of the war, he soon summoned them to come home; around that time, suspicions began to arise among his American friends. By the 1980s, those suspicions had been publicly confirmed. An was honored in his homeland as a national hero.

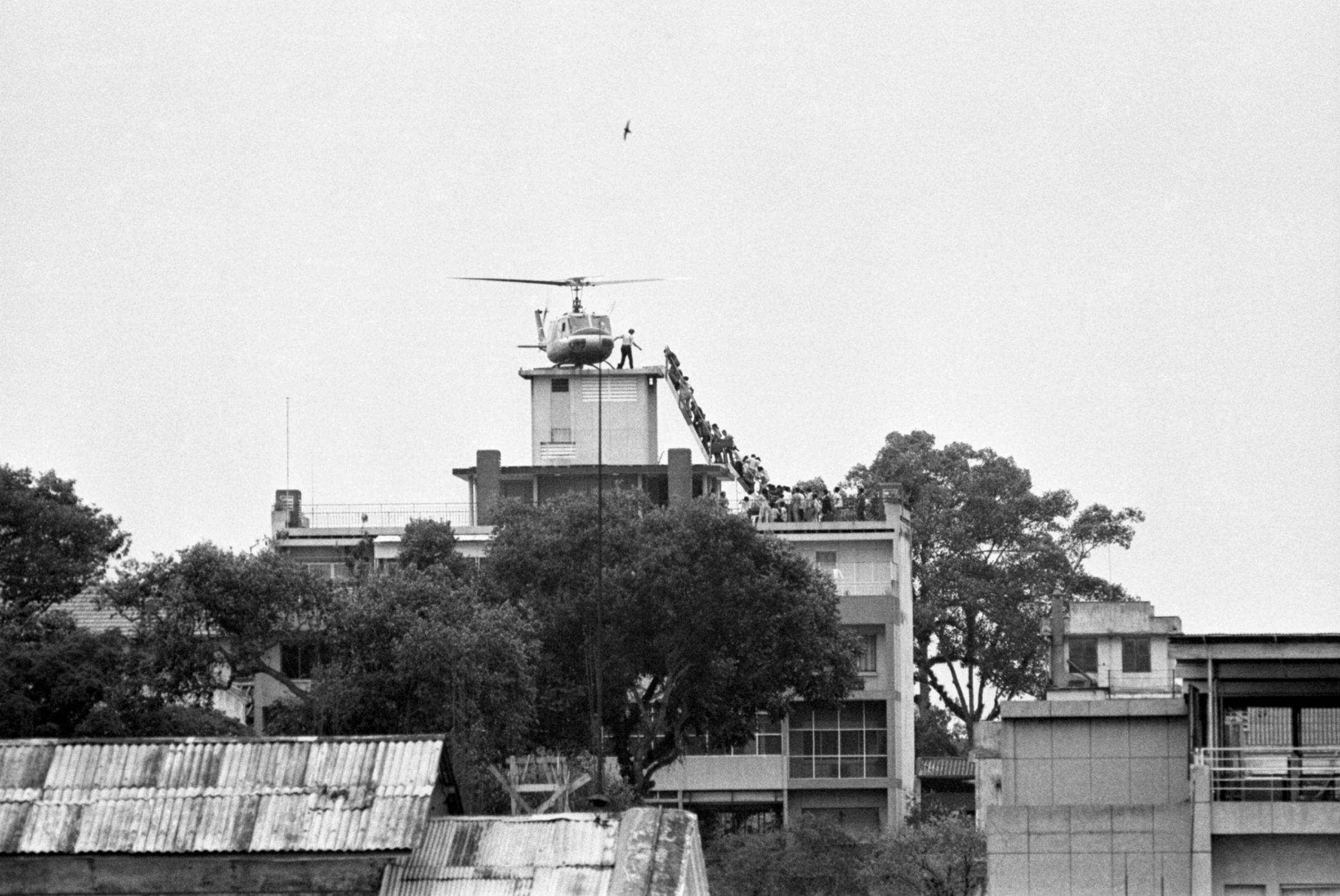

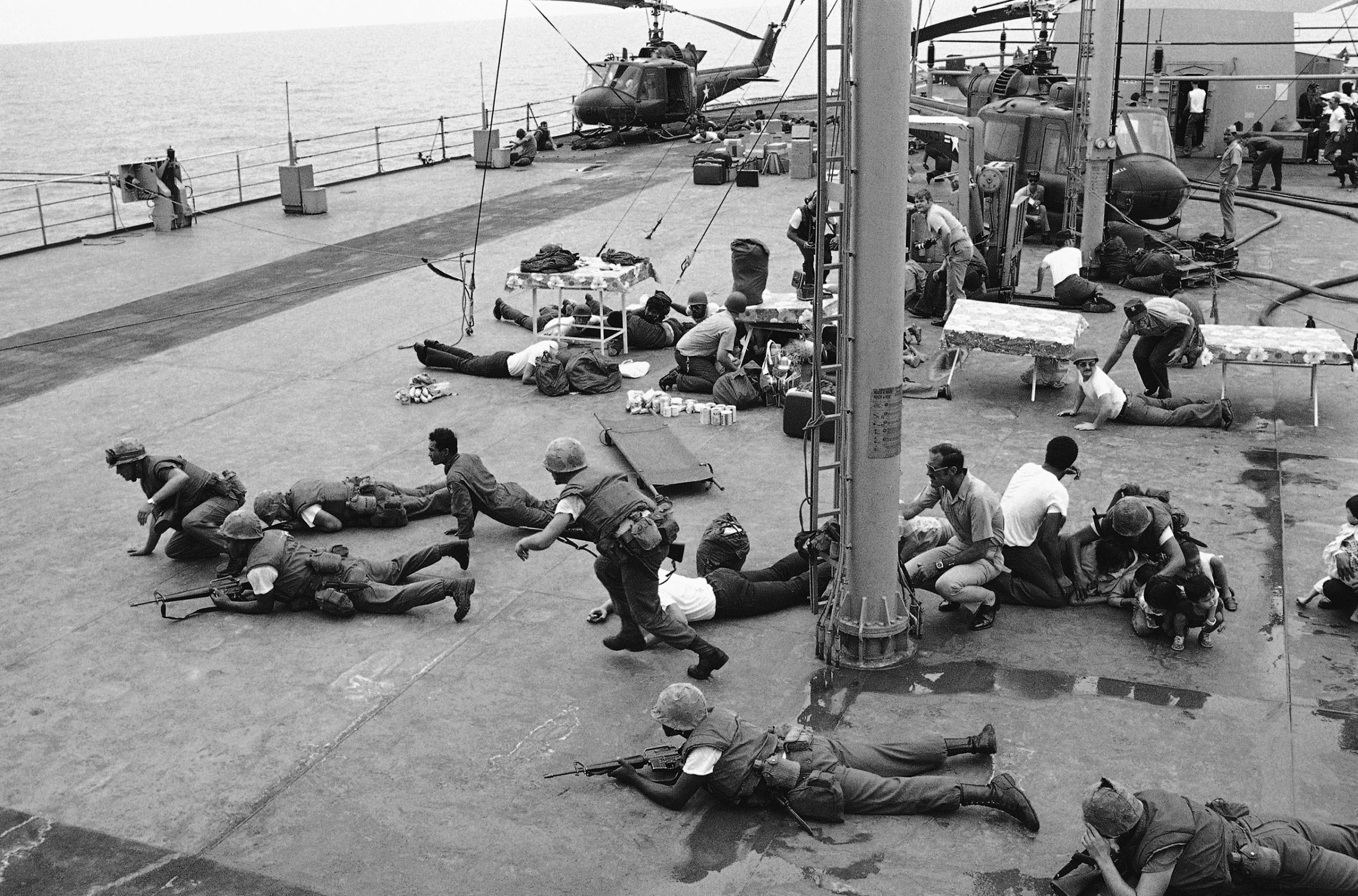

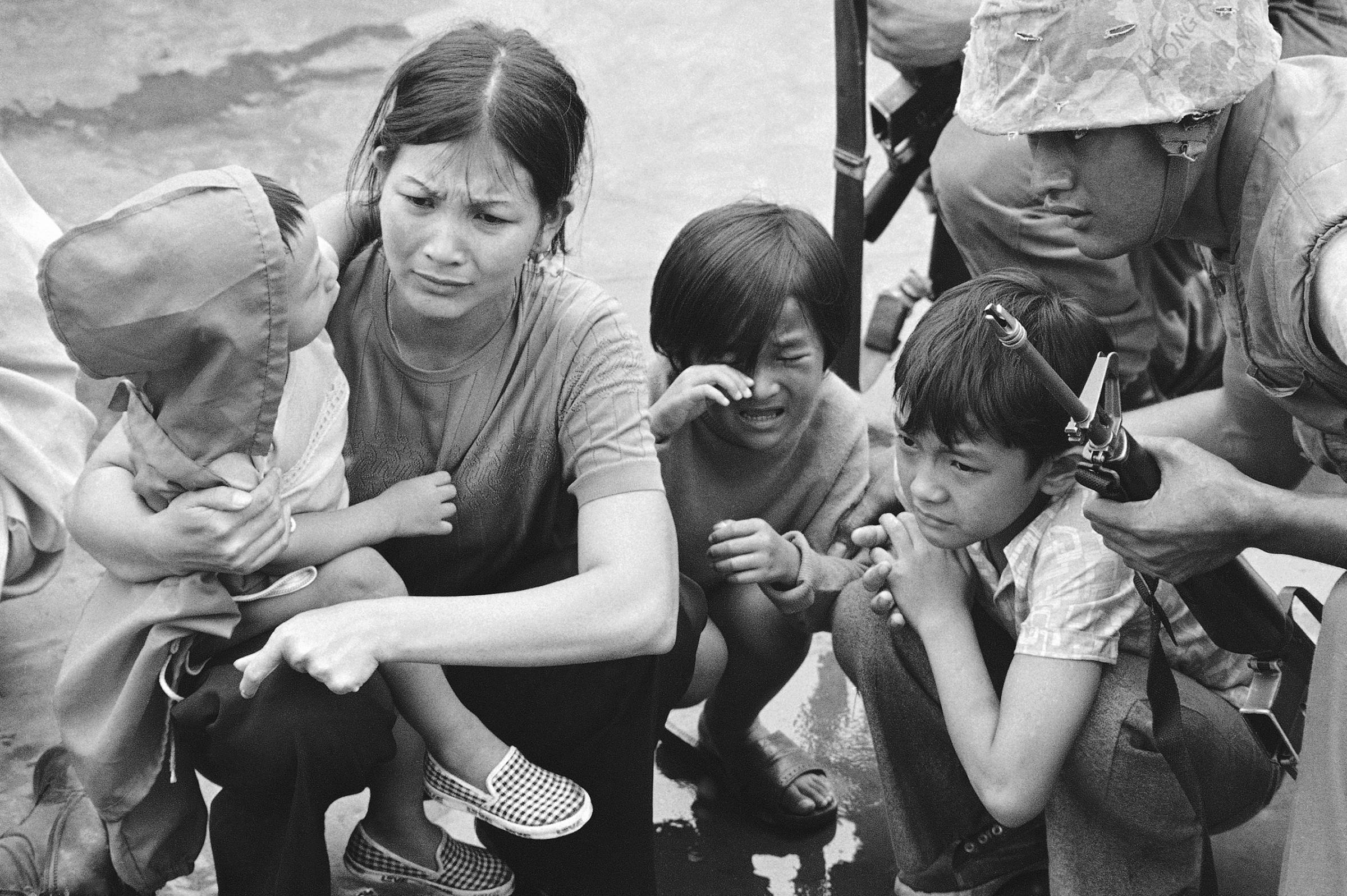

The Last 48 Hours of the Vietnam War in Photos

An never told a lie, Bass says, so he was able to keep his own story straight. He was also able to maintain the respect of his colleagues. Many of his TIME friends met with him on return trips to Vietnam, and several—including Stanley Cloud—later chipped in to help send An’s son to college in the U.S.

“He was a great man. A great man,” Cloud, 78, says, reflecting on that period. “[When I found out] I was surprised but I wasn’t astonished, if you know what I mean.”

“I don’t think he ever purposely gave us misinformation. That’s how he survived. He’d have been killed if he did,” echoes Roy Rowan, now 95, a long-time TIME and LIFE staffer who worked in Saigon for the magazine at the end of the war. Rowan recalls a three-hour-long, highly emotional conversation during which he tried to convince An to save his own life by evacuating with the rest of the staff. An maintained he was staying behind to care for his ailing mother.

His biographers have also been unable to find evidence that he spread falsehoods. “I was hoping to find evidence that the stories had been slanted, but I couldn’t find it,” says Larry Berman, author of the biography Perfect Spy, who notes that An’s story is currently being turned into a 32-part Vietnamese television series.

In fact, it seems more likely that having a spy on the staff helped TIME cover the war more accurately. Cloud recalls a time during the Paris Peace Accord negotiations when Newsweek’s Saigon bureau chief bragged about having the details of the peace plan; TIME asked An to see what he could find so that the magazine wouldn’t get scooped. An brought back the outline of the plan. The story that TIME ran that week, Cloud recalls, was more accurate than Newsweek’s.

An was not without his detractors. Cloud recalls, for example, that Murray Gart, then TIME’s chief of correspondents, felt absolutely betrayed by An. (Gart died in 2004.) Berman says that his book has been criticized by those who feel he’s too sympathetic. At the heart of the matter is the fact that even though An appeared to have been careful not to endanger his colleagues—he intervened in at least one case to keep a TIME correspondent safe—the information he was able to provide to the North was not without military value. “Could his information have led directly to the deaths of American soliders? And if so, should we be rethinking our love for Pham Xuan An?” asks Range. “Personally, [he was] a great guy—but he’s out creating situations which could have killed young men from our side and of course that’s what he was supposed to do. And if that’s what he was doing, you need to think about that.”

Still Range stands by An. When he learned the truth about his former colleague, he felt “disbelief, shock, but not anger,” he says. “Everything was upside-down. So the fact that this turned out to be upside-down seemed like another one of the strange anomalies of the time.”

Berman says that it’s not surprising that, 40 years later, the story of Pham Xuan An is not seen by former friends as a tale of betrayal. An loved America, appreciated the free press, was respected by his colleagues—but he loved his own country more, and wanted it to be independent.

Today, Berman says, most Americans see the war the way that An did, agreeing with him that it would have been better for the Americans to go home.

“An thought, naively, that when the war was over it would be just like the end of the American Civil war, where Lincoln said ‘with malice toward none,’” Berman says. “People hold onto him as symbol of war, but really he’s a symbol of peace.”

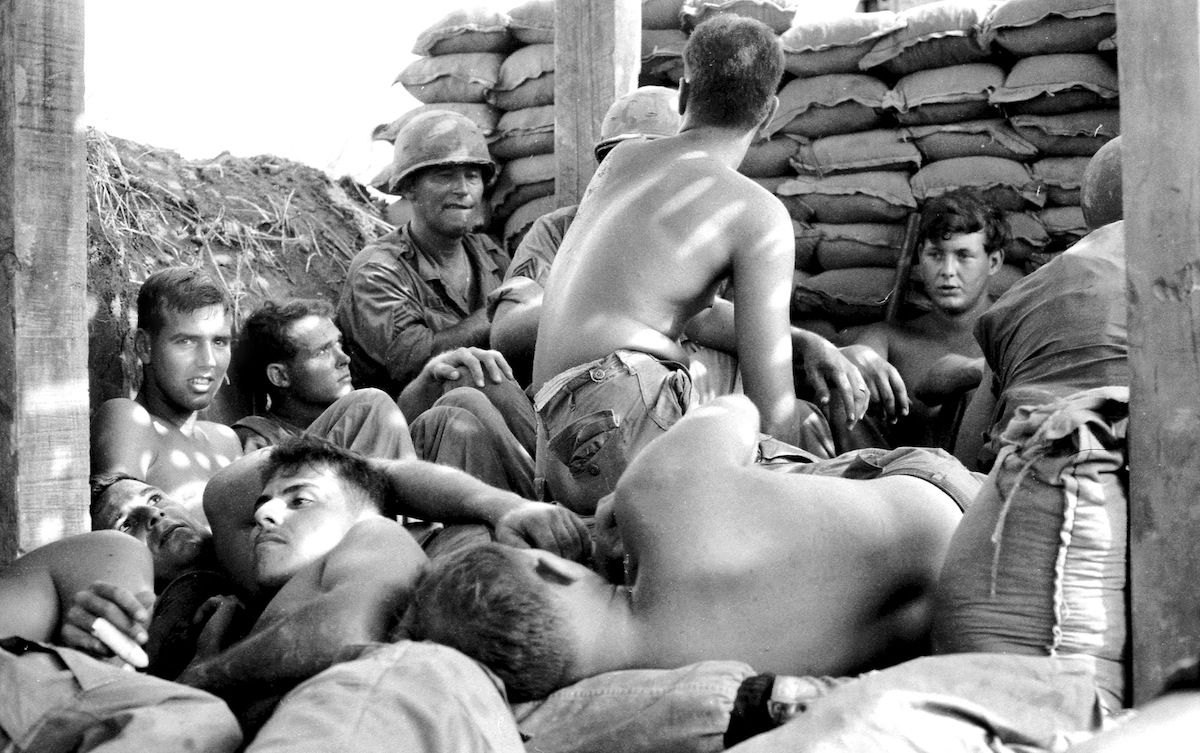

Photographic Memories of a Vietnam Veteran

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com