The Justice Department announced Tuesday it opened a federal inquiry into a Baltimore case involving a man who was arrested earlier this month and later died after an apparent spinal injury, the latest incident of a police-related death of a black man to drive the national debate about race and excessive force.

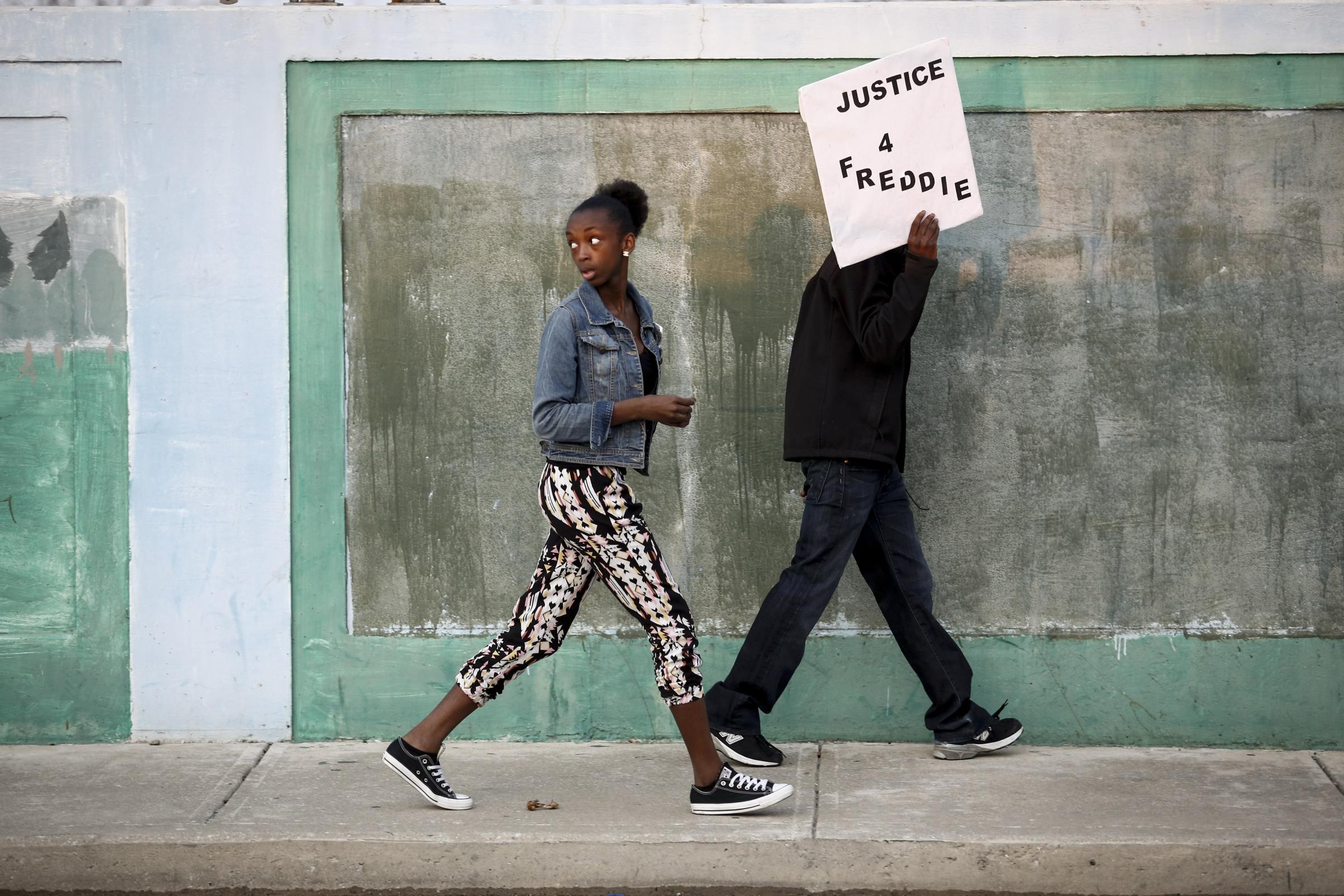

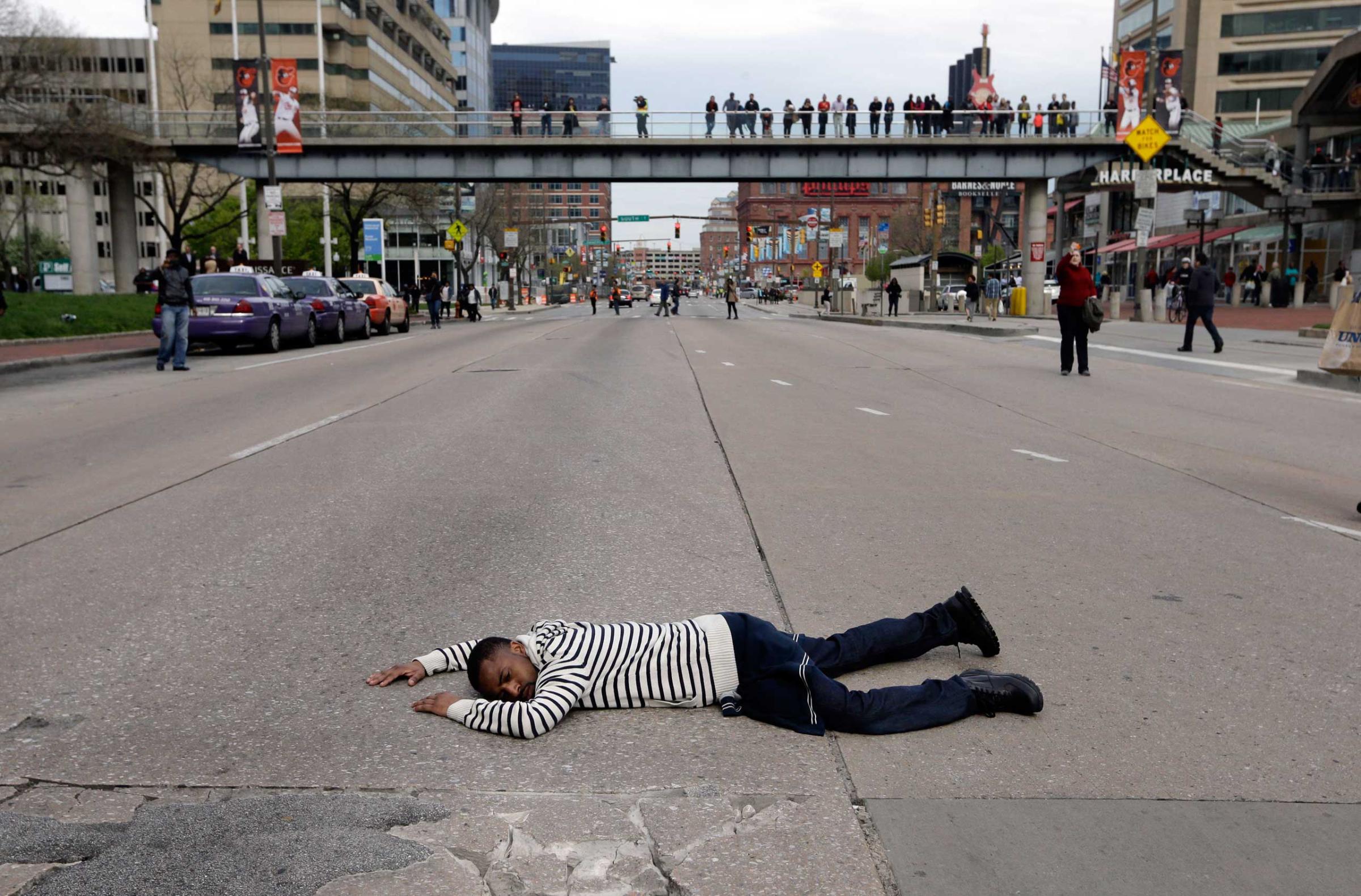

Federal investigators will look into whether the civil rights of Freddie Gray, who died Sunday, had been violated after his arrest on April 12. The incident has ignited protests around Baltimore, a city that has struggled for years to maintain trust between police and residents, and put a spotlight on law-enforcement officials and the mayor as the case continues to raise more questions than answers.

According to the Baltimore police department, which released the names of the six officers involved in the incident and suspended them with pay, Gray was arrested after he “made eye contact” with police and ran. Authorities later said Gray was carrying a knife that was clipped to the inside of his pocket. In a video recorded by a bystander, Gray is seen being placed inside a police van and appears to have trouble walking.

Police have denied using force against Gray, whose spine was described by the family’s attorney as 80% “severed at the neck.” Gray eventually lapsed into a coma and died.

“I know that when Mr. Gray was placed inside that van, he was able to talk,” Baltimore deputy police commissioner Jerry Rodriguez told reporters on Monday. “And when Mr. Gray was taken out of that van, he could not talk, and he could not breathe.”

William “Billy” Murphy, Jr., an attorney representing Gray’s family, told TIME the bystander’s video is “suggestive of the injury happening during arrest.”

“We know that while in police custody, this guy was extraordinarily injured,” he said. “What we don’t know yet is exactly who did it, why they did it or how they did it.”

Witness Protests in Baltimore Over the Death of Freddie Gray

Gray was arrested near the Gilmor Homes public-housing complex, which is in a neighborhood that has experienced years of frayed relations between residents and law-enforcement officers. “There’s a huge amount of distrust in this community,” says Baltimore city councilman Nick Mosby, who represents the district where Gray was arrested. “It’s an us-vs.-them type of approach.”

The complex itself has also had problems. In 2010 a federal grand jury indicted 22 people on drug-conspiracy charges centered on the residences. In 2014 a woman accused Baltimore police of using a Taser on her as she held her 11-month-old brother within the complex. Police denied the allegations and said she was not holding the baby at the time.

“What you have is a terrible, terrible police-community relationship, and you essentially have the police with the unenviable task as they would see it trying to take control and keep a lid on neighborhoods that are so ridden with hopelessness and anger and disconnected people,” says Barbara Samuels, an ACLU attorney who has worked on behalf of black public-housing residents. “But at the same time, they don’t feel protected at all by the police. It’s just a very toxic situation.”

The Gray incident follows several high-profile cases around the U.S. involving police use-of-force, including incidents in Ferguson, New York City, Cleveland and North Charleston, S.C., in which police actions contributed to the deaths of black men.

Baltimore police commissioner Anthony Batts has called for changes in the way the city’s police move arrested individuals and said the department would re-examine how it provides medical attention to those in custody. Baltimore Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake has pledged that officials will conduct a thorough review of the incident to determine how Gray sustained life-ending injuries.

“This is a very, very tense time for Baltimore city, and I understand the community’s frustration,” Rawlings-Blake said in a news conference Monday. “I understand it because I’m frustrated. I’m angry that we are here again, that we have to tell another mother that her child is dead. I’m frustrated not only that we are here, but we don’t have all of the answers.”

But repairing trust between citizens and the police in Baltimore is something that will take far longer than determining how and why Gray died.

“Just like in Ferguson, Cleveland and North Charleston, people are saying, I’d rather the police not come here,” says Mosby, the councilman. “Maybe I don’t want my neighbor’s son pulled over and ultimately wind up a victim of some kind of incident that could’ve been handled a different way.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- 22 Essential Works of Indigenous Cinema

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com