The Norwegian Journal of Photography (NJP) has released the latest issue of its biennial survey of the Scandinavian country’s contemporary documentary photography scene, showcasing the work of eight photographers.

The publishers — photographers and photo editors Rune Eraker, Laara Matsen and Espen Rasmussen — combed through close to 100 applications and submissions to arrive at its final list of eight photographers, using funding from the Fritt Ord Foundation, a non-profit devoted to freedom of expression, to produce the high-quality book.

“We look for strong voices,” Espen tells TIME, “and we also look for photographers who challenge the term ‘documentary photography’. Do they have a style, something to tell us, do they surprise us or challenge us? Do they create any feelings for us as a viewer? And we consider the project proposals to see if the project is original, if it has relevance and whether it is possible to work on during the 18 months they have available before the book deadline.”

Once chosen, the NJP works with these photographers to craft and edit their long term projects, and to find financial support. It also offers them seminars and classes with international lecturers.

TIME talked to the eight photographers.

Jonas Bendiksen, a member of Magnum Photo, has shot for major publications around the world, including National Geographic. Yet, for the past two years, he’s taken a different approach, joining the staff of Bladet Vesterålen, a local newspaper with a circulation of just 8,000. “I realized that after 15 years of photography, I had never worked for a newspaper,” he told TIME. “I love newspapers. In a way, for me to do a daily beat has been somewhat of a romantic dream for some time. When my fiancé, now my wife, got work as a doctor in a small community in the north of Norway, I felt this was a chance, and I asked Bladet Vesterålen if I could work for them. They gave me a position, and sent me out in the local communities. For me, it was a personal way of somewhat giving a homage to the institution of the local newspaper, which is sort of the backbone of everything a documentary photographer or photojournalist does. It is storytelling on a very direct level, on a daily basis. There was something really refreshing for me to take pictures one day, have it published the next, and meet the person in the picture in the supermarket the next day.”

Mathilde Pettersen was first introduced to photography in high-school when she discovered the darkroom. “Seeing the results of my work coming to life, I understood that this was my mission and that I was hooked for life,” she said. “I have been working with this project since 2008 when I was pregnant with my first child. I wanted to document the changes in the female body and the arrival of a child. I am exploring human nature, motherhood, the ‘circle of life’.”

Anne-Stine Johnsbråten was first given a camera to document her first day at school when she was seven years old “I still vividly remember waiting for the postman to deliver the processed film after the two weeks wait.” Her series on the economic, ethnic and cultural differences between east and west Oslo help complicate our picture of Norwegian society. “This is a very personal project to me,” she said. “Growing up in the eastern part of Oslo, the division of the city has always puzzled me, and the idea for the project has been brewing for years. Finally, NJP was the perfect excuse to get the project started.”

Knut Egil Wang first photographed a bridge construction project from start to finish when he was in high-school. “I soon realized that the images I valued the most were those from before the construction work began,” he said. “Small changes happen constantly and often unnoticed. Suddenly all of them make a big difference. This fascination for how soon our present becomes history made me want to be a documentary photographer.” For his current project, he says, “I have been traveling along the San Andreas Fault line before ‘The Big One’ strikes. Largely invisible, yet capable of massive destruction: we know a lot about earthquakes, but what can we do about it? Not much. Life goes on as if nothing is going to happen.” In fact, Knut says, “When I got there, I was surprised to find that many [people] didn’t even know they were living on the fault line.”

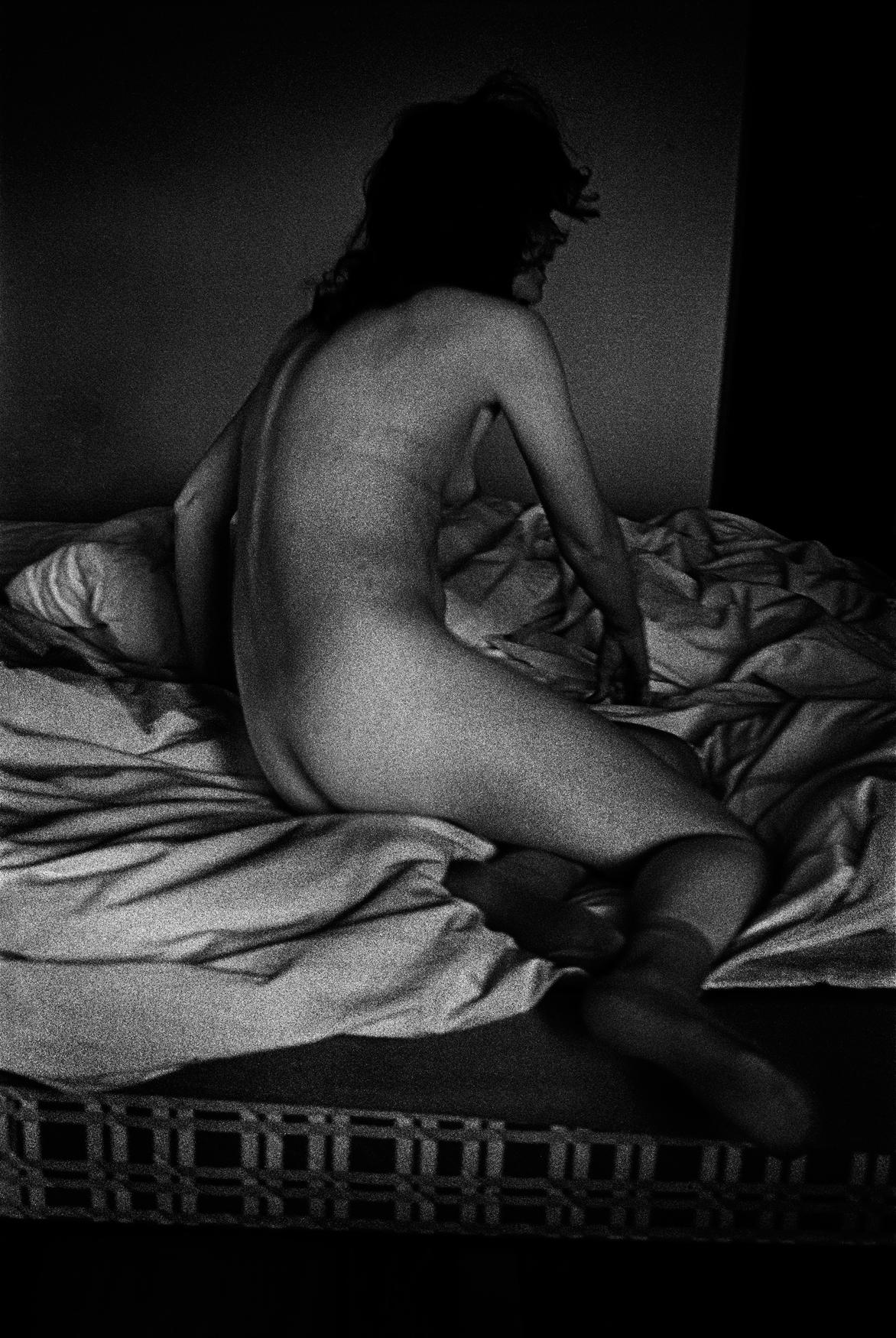

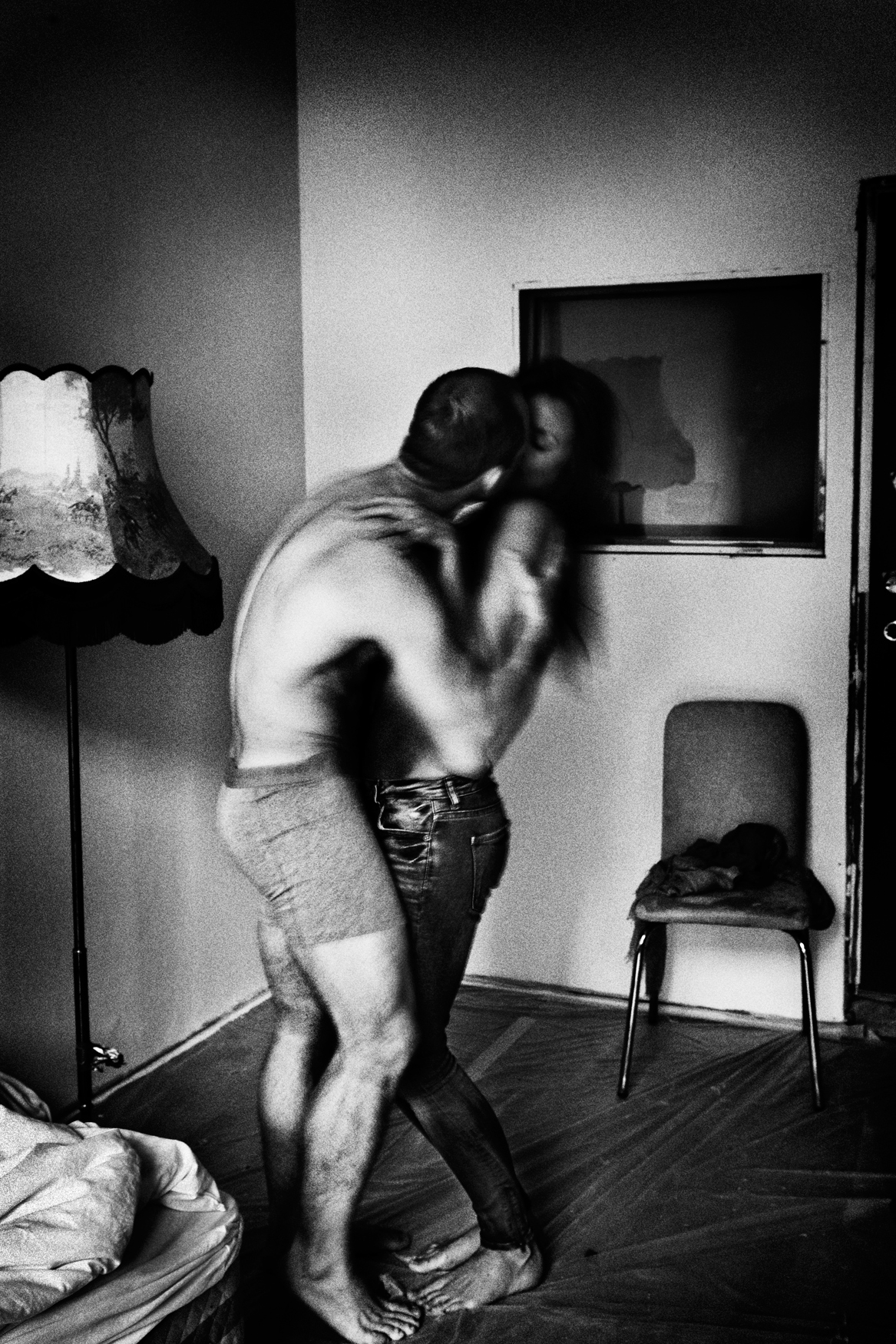

Margaret M. De Lange said that photography has always moved her. “Some of my earliest memories of this were magazines with photojournalism from the Vietnam War. The images made a lasting impression on the young girl I once was. [Now] I’m always taking pictures of the people and situations around me. As time goes by patterns emerge and my projects take shape. In this project I’m exploring vulnerability and the strength it takes to allow yourself to be seen at your most exposed. It examines intimacy in all its shapes and sizes.”

Terje Abusdal started shooting photos in his early teens. “I built a darkroom in our sauna and learned by doing and reading books. I picked it up again seriously in 2011 when I went on a month-long road trip with the Greek photographer [and Magnum member] Nikos Economopoulos, and since then I haven’t looked back.” Recalling the origins of his current project, Terje said “I used to be the next door neighbor to a music festival in Oslo. For most of the days I didn’t have a ticket, and I hated lying in bed listening to the music with everybody else having fun. So I took my tent and fled to the island, as a festival refugee. Out there I found another world of its own, a hidden gem of anarchy just 15 minutes by boat from the center of town. It is full of real interesting characters and I found that through my photography I had a passport to approach anyone I wanted. The project explores the temporary identity of an island where people from all walks of life becomes neighbors for one season at a time. How does where they are and who they are with form them?”

Tomm W. Christiansen became a photographer almost by accident. “It was in 1994. I lived in Sweden at the time and didn’t know what to do with my life,” he said. “Photography was a hobby. For some reason, the photo editor of the Gothenburg Post, Anders Hofgren, didn’t just dismiss me when I asked him for a chance to become a freelancer for the paper. He lent me a camera and even his car and sent me out to take a picture of an old lady running a voluntary telephone service. I immediately realized I had found my place in life.” Today, though his project The Bloodlands he is exploring how the violent past affects the present life of the people in Berdychiv, a small town in Ukraine. “After my first trip to Ukraine I realized that Bloodlands is not only a geographical term, it is also a state of mind. Decades of war and unrest has profoundly affected the people living here.”

Ivar Kvaal’s father used to be a photographer, and introduced him to the art form at an early age. His current project is about a peculiar and recurring UFO sighting near a small town in Norway, featured on TIME LightBox earlier this week. “I strive for aesthetically appealing and interesting photographs, conveyed by an underlying idea or theme,” he said. “The resulting images are often lyrical and of a fictitious nature, revealing beauty in the subtle details. I want my images to suggest stories rather than dictate a narrative. Communicating feelings are just as important as telling the story.”

Myles Little is an associate photo editor at TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Breaking Down the 2024 Election Calendar

- How Nayib Bukele’s ‘Iron Fist’ Has Transformed El Salvador

- What if Ultra-Processed Foods Aren’t as Bad as You Think?

- How Ukraine Beat Russia in the Battle of the Black Sea

- Long COVID Looks Different in Kids

- How Project 2025 Would Jeopardize Americans’ Health

- What a $129 Frying Pan Says About America’s Eating Habits

- The 32 Most Anticipated Books of Fall 2024

Contact us at letters@time.com