This post is in partnership with the History News Network, the website that puts the news into historical perspective. The article below was originally published at HNN.

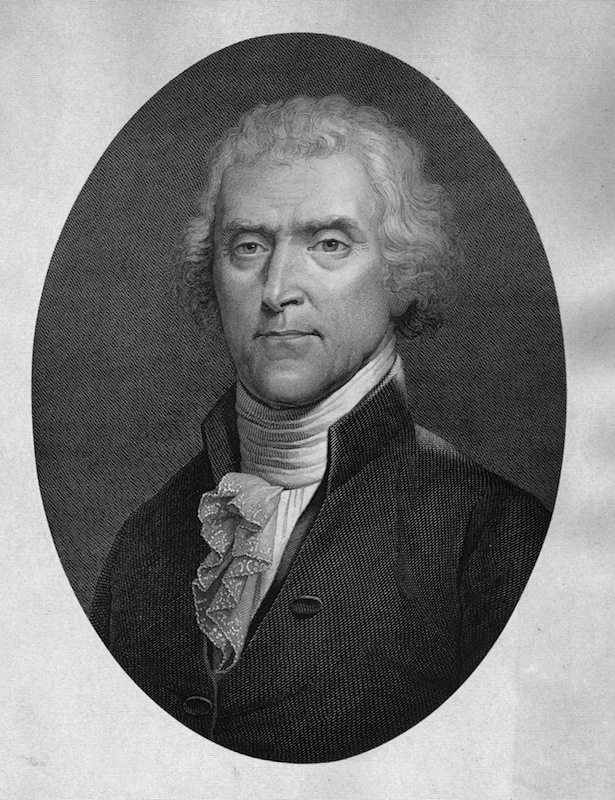

Thomas Jefferson has been problematic for historians and divisive for culture warriors. An idealist who crafted language that remains beautiful and enduringly quotable, he has more recently stood in for the persistence of states’ rights and racial injustice. He has, however, never lost the universality expressed by Mikhail Gorbachev during a pilgrimage to Monticello, when the Russian affirmed that as he was conceiving reform in the Soviet Union he recurred to a college text that expounded Jefferson’s political principles.

Jefferson is a featured player in the political memory game as it has been practiced in America over the last century. Every country needs its national origins story. Ours, wearing the garb of American exceptionalism, has given generations a narrative, dating to 1776, that pronounces the moral worth of the founders and their humane principles. In this project, Jefferson is the principal author of the ingenious, hopeful script that we commemorate on select holidays and reintroduce in times of war or perceived danger. As “democracy’s muse,” he alternately soothes and buoys a militarily strong yet frustrated, disoriented nation marked by social contradictions. It is that phenomenon which I examine in my new book. I cover reimagined Jeffersons across the presidencies of the modern era, in debates on Capitol Hill, and among the columnists and popular authors who have aimed to bring the concept of Jeffersonian democracy up to date.

The political Left “owned” Jefferson from the New Deal through the 1960s; yet Ronald Reagan, as much a Jefferson lover as any Democrat, went far in converting the eloquent founder to the conservative cause–where he has largely remained to this day. Curiously, it is only on the Right that we find those who deny the link between Jefferson DNA and the mixed-race offspring of Monticello slave Sally Hemings; on the Right it is thought that plantation sex is a diminution of founding “greatness” and a threat to the moral underpinnings of the founding narrative.

Franklin D. Roosevelt was integrally involved in the planning and execution of the Jefferson Memorial, which he dedicated on the Virginian’s 200th birthday, April 13, 1943. Thousands gathered to witness the event. “Thomas Jefferson believed, as we believe, in man,” the president said on that day. Enlisting Jefferson in the ongoing struggle against Hitler, he continued: “He believed, as we believe, that … no king, no tyrant, no dictator can govern for them.” In conclusion, FDR explained the choice of the quote that wraps around the interior of the dome, which expressed “Jefferson’s noblest and most urgent meaning.” It reads: “I have sworn before the altar of God, eternal hostility against every form of tyranny over the mind of man.”

It was actually a line Jefferson had written in 1800 to Dr. Benjamin Rush, in reaction to the Christian Right of his day, which considered Jefferson an atheist and feared in a Jefferson presidency an abandonment of religious morals and imposition of non-belief. The recipient of the letter believed, unlike Jefferson, that Jesus was divine. The “altar of God” allusion was a subtle means to reach a man of faith, while stating that more suspicious men of faith need not fear his intrusion into anyone’s right of conscience. A few months after the letter to Dr. Rush, in his First Inaugural Address, the third president sent new signals, intentionally referring to Americans’ “benign” religion, “practiced in its various forms”; and he went on to say that the “blessings” of an “overruling Providence” needed only a “wise and frugal government” to complete the happiness of citizens in their new republic.

He spoke presidentially. The common invocation of “Providence,” like presidential recurrence to “God bless the United States of America” these days, was meant only to soothe. The historical Jefferson wrote most forcefully–and privately– about the dangers of “metaphysical speculations” and the need to employ reason to confront the “mischievous” dogmas repeated by ill-informed (or deceptive, manipulative) preachers.

Of course, not everyone regards the historical Jefferson with calm deliberation. Extracting Jefferson quotes has been a hobby of many over the years, and a major problem for single-issue politicians who have endeavored to translate their Jefferson into a spokesman for whatever they advocate. Public figures are guilty of removing the most emotionally resonant of the founders from historical context, and will often mingle legitimate phrases with invented ones. Monticello’s research department actively susses out spurious Jefferson quotes and posts explanations on its website. Channeling Jefferson during his unsuccessful run for the Republican nomination in 2012, Newt Gingrich told a questioning voter in New Hampshire that Jefferson, who grew hemp, would, if alive today, impose severe penalties for marijuana possession. Adoring Jefferson, Gingrich repeatedly decried the “radical secularists” who were ruining America.

I call this, somewhat tongue-in-cheek, “Jefferson abuse.” Of recent vintage, to complete the example of Jefferson’s religious views, is David Barton’s dramatic recovery of an evangelical Jefferson in his abortive book of 2012 (since pulled from the shelves by his publisher), titled The Jefferson Lies. Barton combined his stern rejection of Jefferson-Hemings liaison as a moral impossibility with his insistence that Jefferson had never advocated “a secular public square.” His Jefferson “regularly prayed, believing that God would answer his prayers for his family, his country, the unity of the Christian church, and the end of slavery.”

The “wise and frugal government” of Jefferson’s First Inaugural has become, since the 1980s, a touchstone for fiscal conservatives. At the Jefferson Memorial on July 3, 1987, President Reagan broadcast a “Jeffersonian” dictum, citing the magnetic founder’s hope for a constitutional amendment “taking from the federal government the power of borrowing.” For Reagan, big government posed a threat to liberty as granted by Jefferson and his cohort. Ironically, like Reagan, Jefferson was an enemy of spending who ran up a sizeable debt.

Distortion of the historical Jefferson reminds us that people believe what they want to believe. Our democratic politics actually depends on a mass psychology that advances through artful manipulation. We may protest the “long train of abuses” (to quote from the Declaration) that attach to statements made in Jefferson’s name; but he continues to occupy a privileged position as we converse with the past and seek to reconcile it, somehow, with our relatively disorganized present. Whoever “owns” Jefferson (or the collective founders) takes themselves to be inheritors of America’s essential ideals.

Andrew Burstein is the Charles P. Manship Professor of History at Louisiana State University. His most recent book is “Democracy’s Muse: How Thomas Jefferson Became an FDR Liberal, a Reagan Republican, and a Tea Party Fanatic, All the While Being Dead.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com