Ashley Broadway-Mack was living in North Carolina in in 2013 when her wife Heather Mack, a Lieutenant Colonel in the U.S. Army, had their child Carly. But same-sex marriage wasn’t legal in North Carolina at the time, meaning Carly, now 2, couldn’t have Broadway-Mack listed as a parent on her birth certificate. Brodway-Mack eventually managed to become a legal parent to Carly after she traveled to South Carolina (where so-called “second-parent” adoptions are legal) and spent thousands of dollars to legally adopt her. Same-sex marriage became legal in North Carolina last October.

“We just want to be recognized lawfully like every other military couple and couple in the U.S,” Broadway-Mack told TIME in an interview this week. “We want our marriage to be recognized and our kids to be protected. Men and women in uniform are fighting for our rights and can’t be given the same rights they fight for.”

Stories like Broadway-Mack’s are behind a legal brief that former military officials filed to the Supreme Court ahead of hotly anticipated oral arguments next week about whether states can ban same-sex marriage—arguments many think will end in the high court ruling that marriage is a constitutionally protected right. The brief, reported by the New York Times, argues that the inconsistent state laws on same-sex marriage hurt same-sex married families, and ultimately military readiness. Gay couples in the military move frequently, and have little—if any—choice in deciding where they live. If they move from a state that recognizes their union to one that doesn’t, they are at risk of losing protections and benefits, such as spousal veteran’s benefits distributed by the Department of Veterans Affairs.

”Those willing to risk their lives for the security of their country should never be forced to risk losing the protections of marriage and the attendant rights of parenthood,” the brief argues, ”simply because their service obligations require them to move to states that refuse to recognize their marriages.”

Broadway-Mack, whose wife is stationed at Fort Bragg in North Carolina and who made headlines in 2013 when she was denied entrance to Association of Bragg Officers’ Spouses, said that for gay couples who have children, the issue becomes that much more urgent.

“Before when it was just Heather and me, we were just used to it,” she said. “Now that there are kids involved, it is extremely stressful.”

Roya and Jennifer Cintron, a couple in their early 30s who both serve in the Army, met at Fort Bragg in 2009 when they were en route to their deployments in Afghanistan. They married in New York in 2013. But in February, the couple moved from New Jersey, where their marriage was legally recognized, to Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Texas, where same-sex marriage is not legal.

Roya gave birth to the couple’s twin girls, who are now almost a year old, in New Jersey. And while both parents’ names are on the girls’ birth certificates, Jennifer, who did not give birth to the girls, now has to apply to legally adopt her daughters. Roya Cintron said she was optimistic about the sea change in policies and perceptions around same-sex marriage that have been sweeping the country (the “don’t ask, don’t tell” law banning openly gay people from serving in the military was repealed in 2010). But she said the patchwork of rules still makes for anxious parents, especially in military families where at least one parent could be deployed away at any moment.

“You just never know where the military going to send you,” she said, “even overseas.”

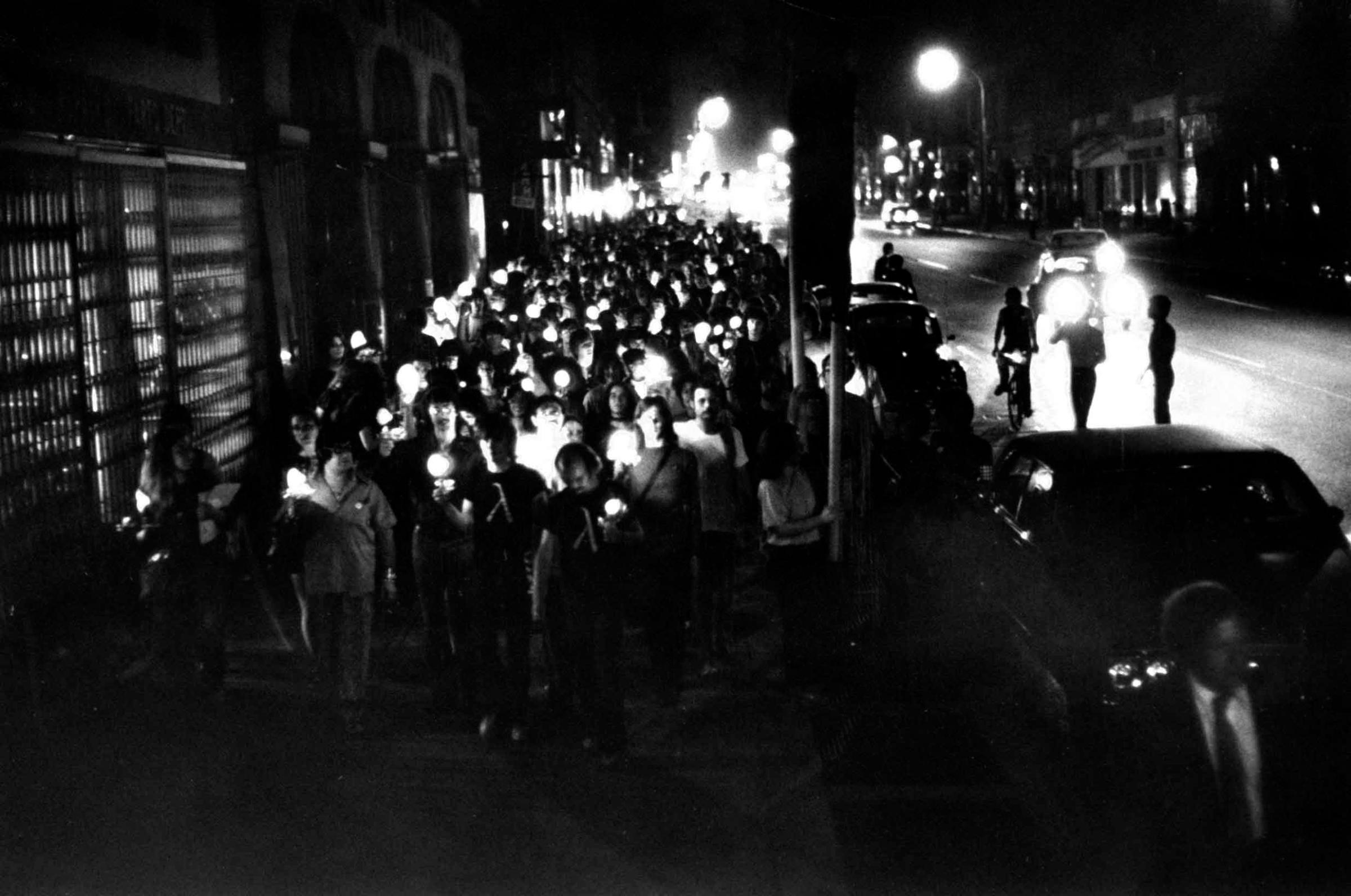

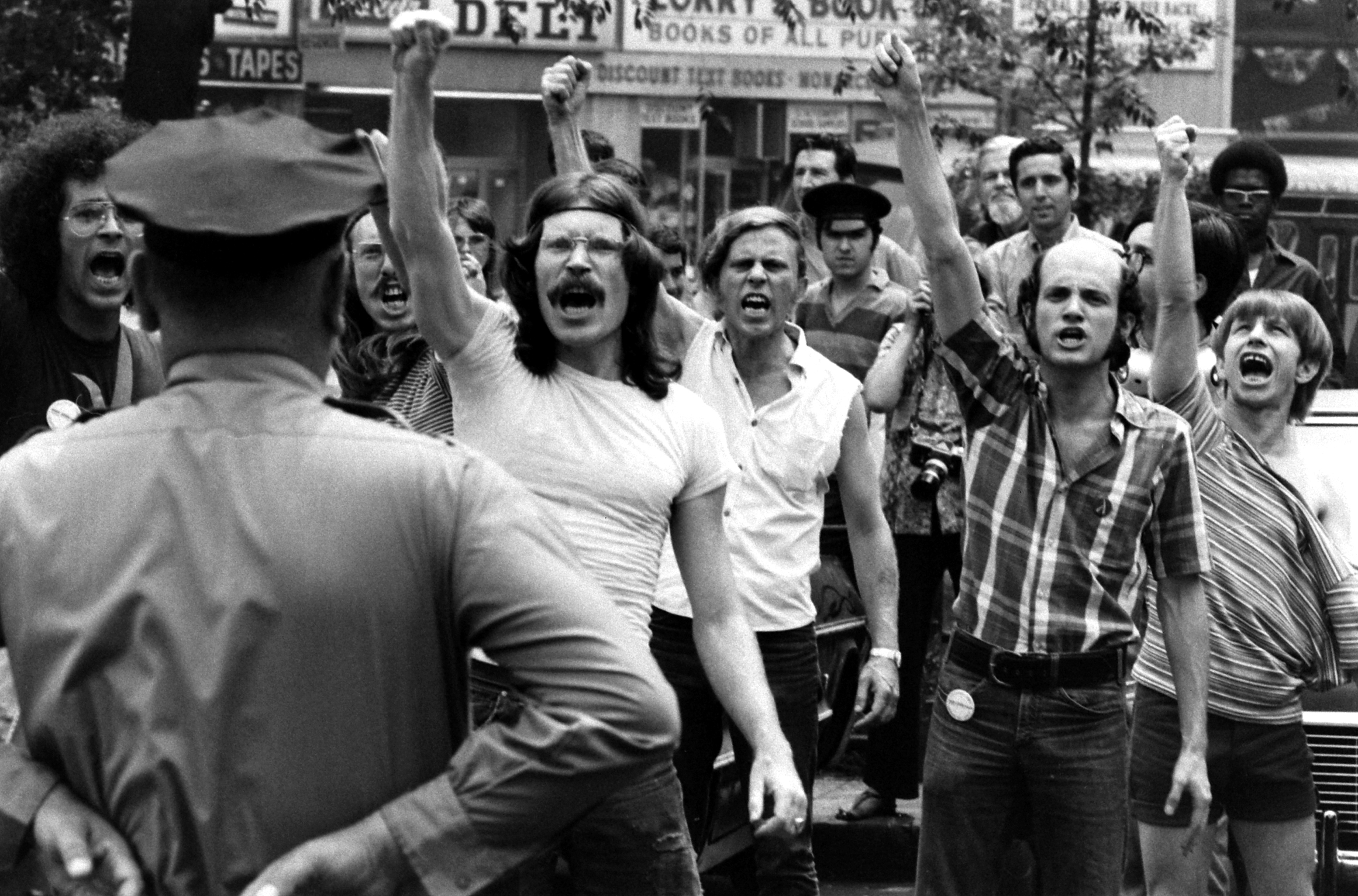

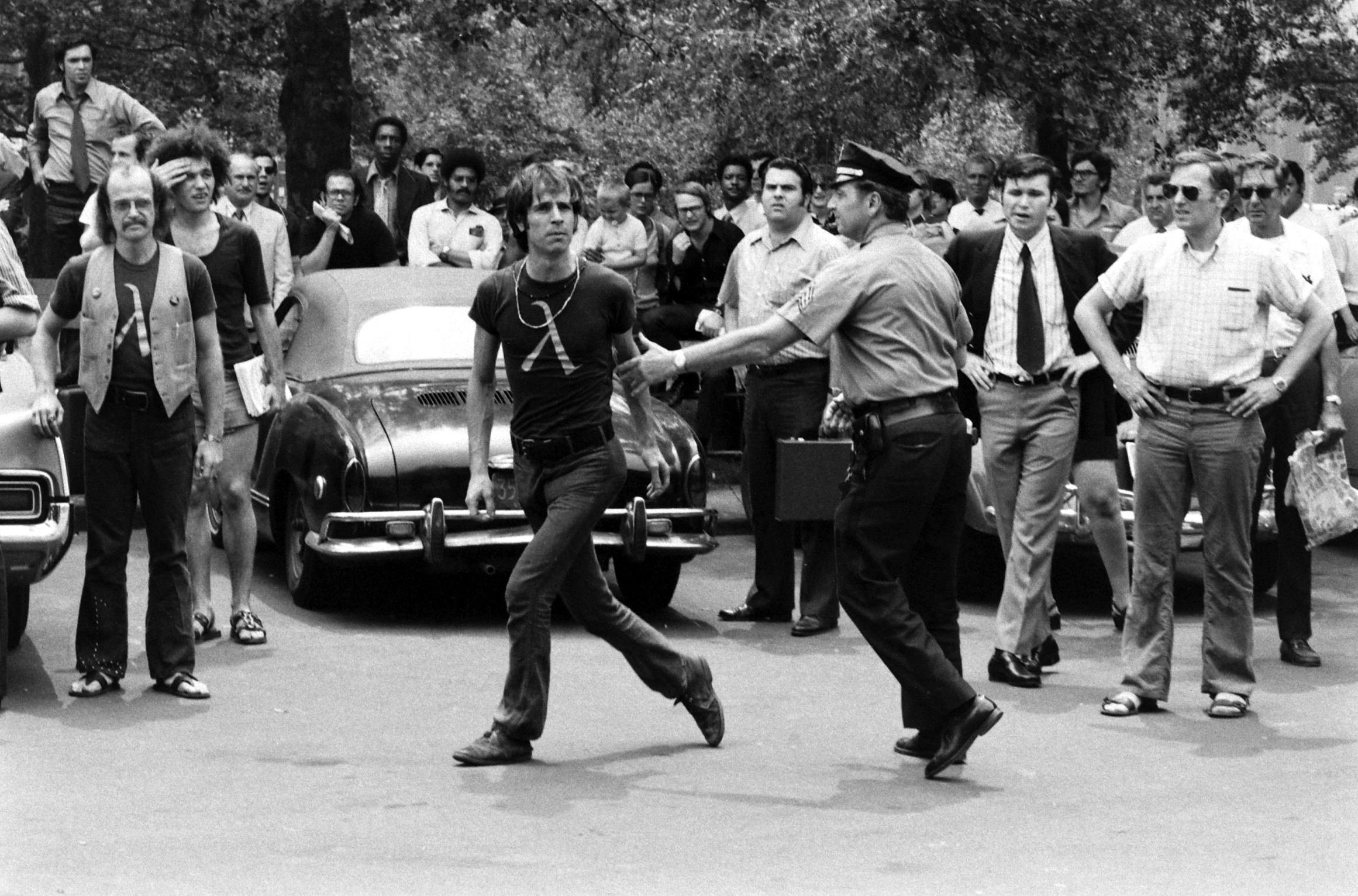

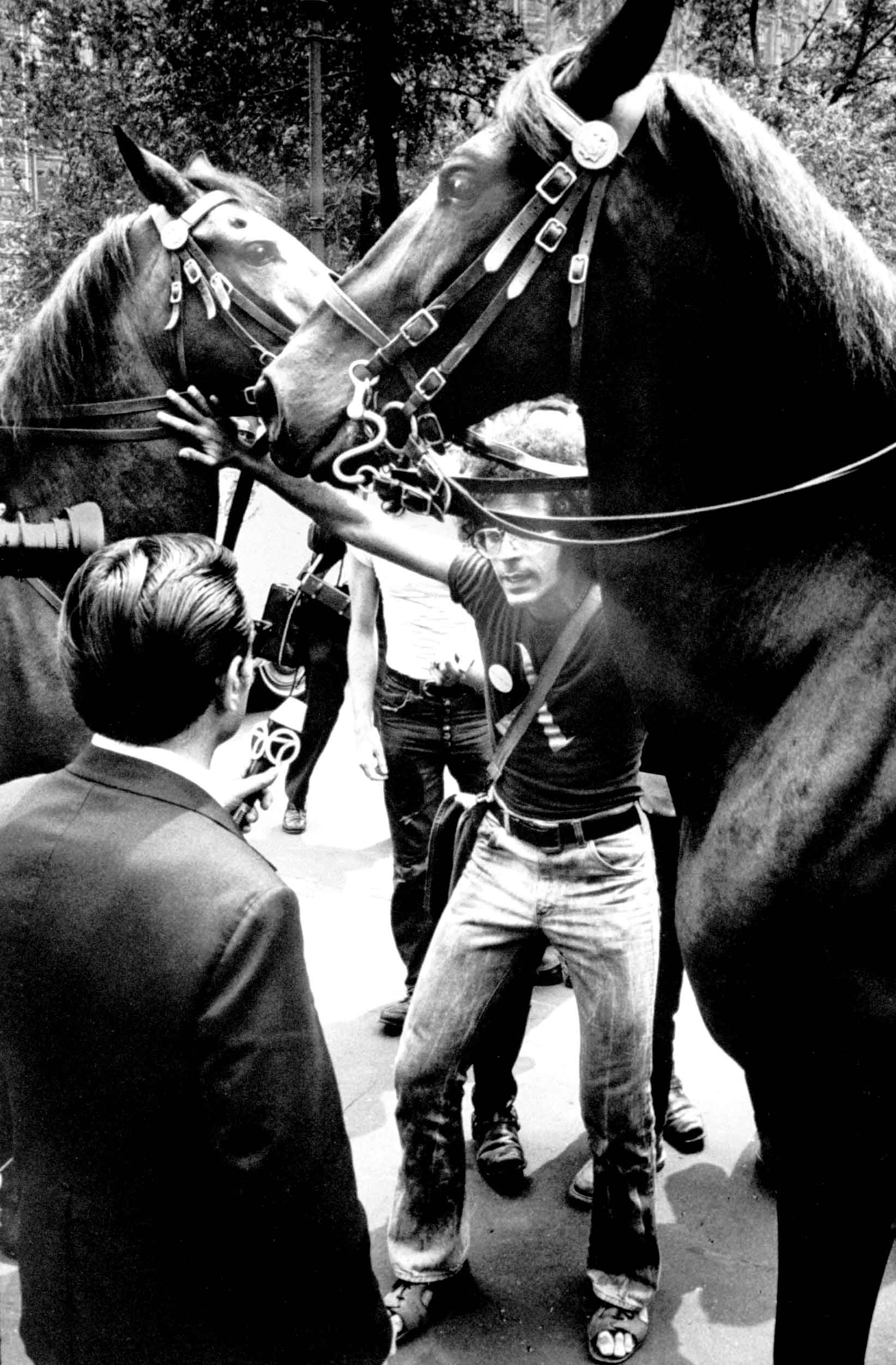

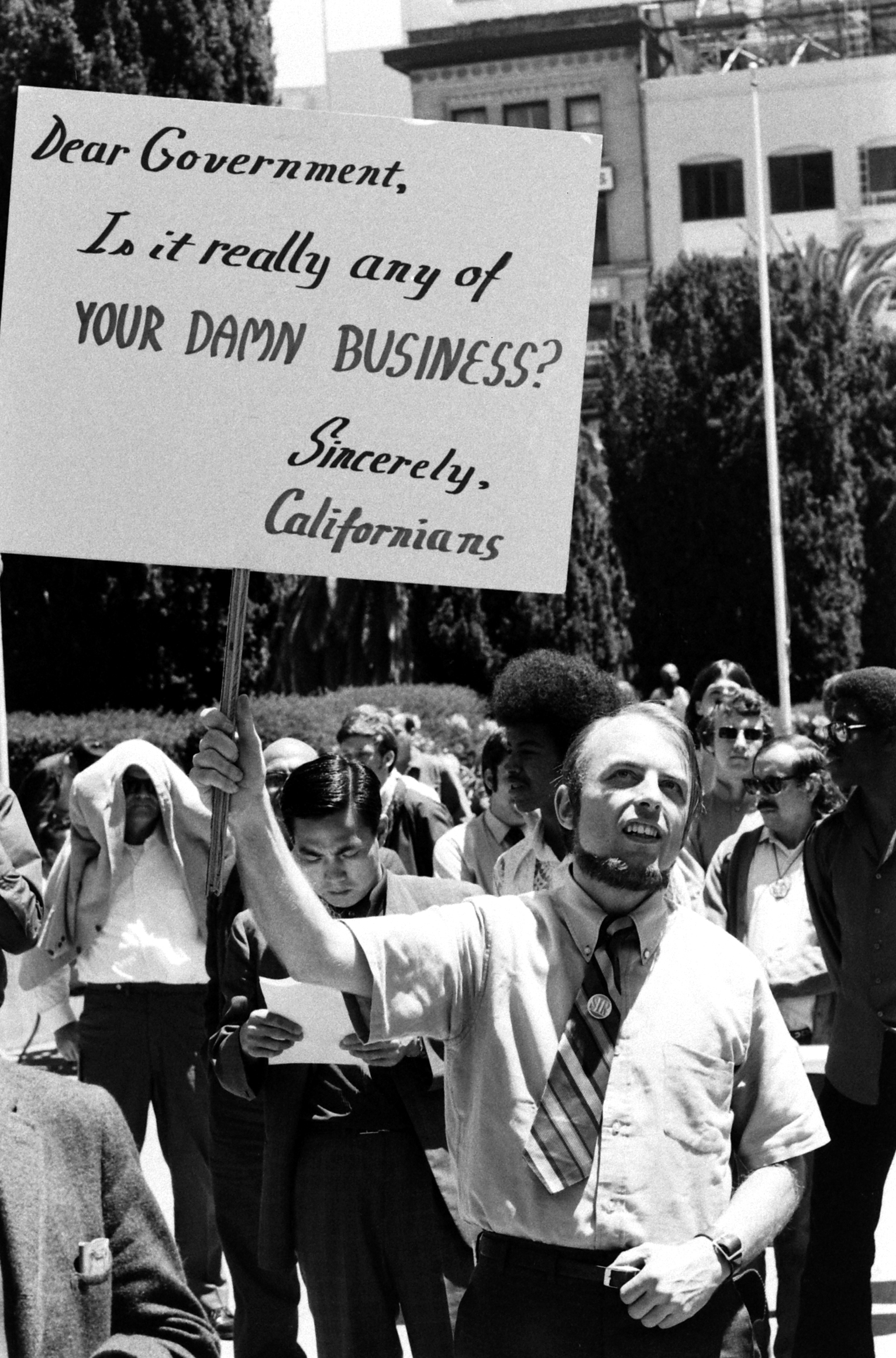

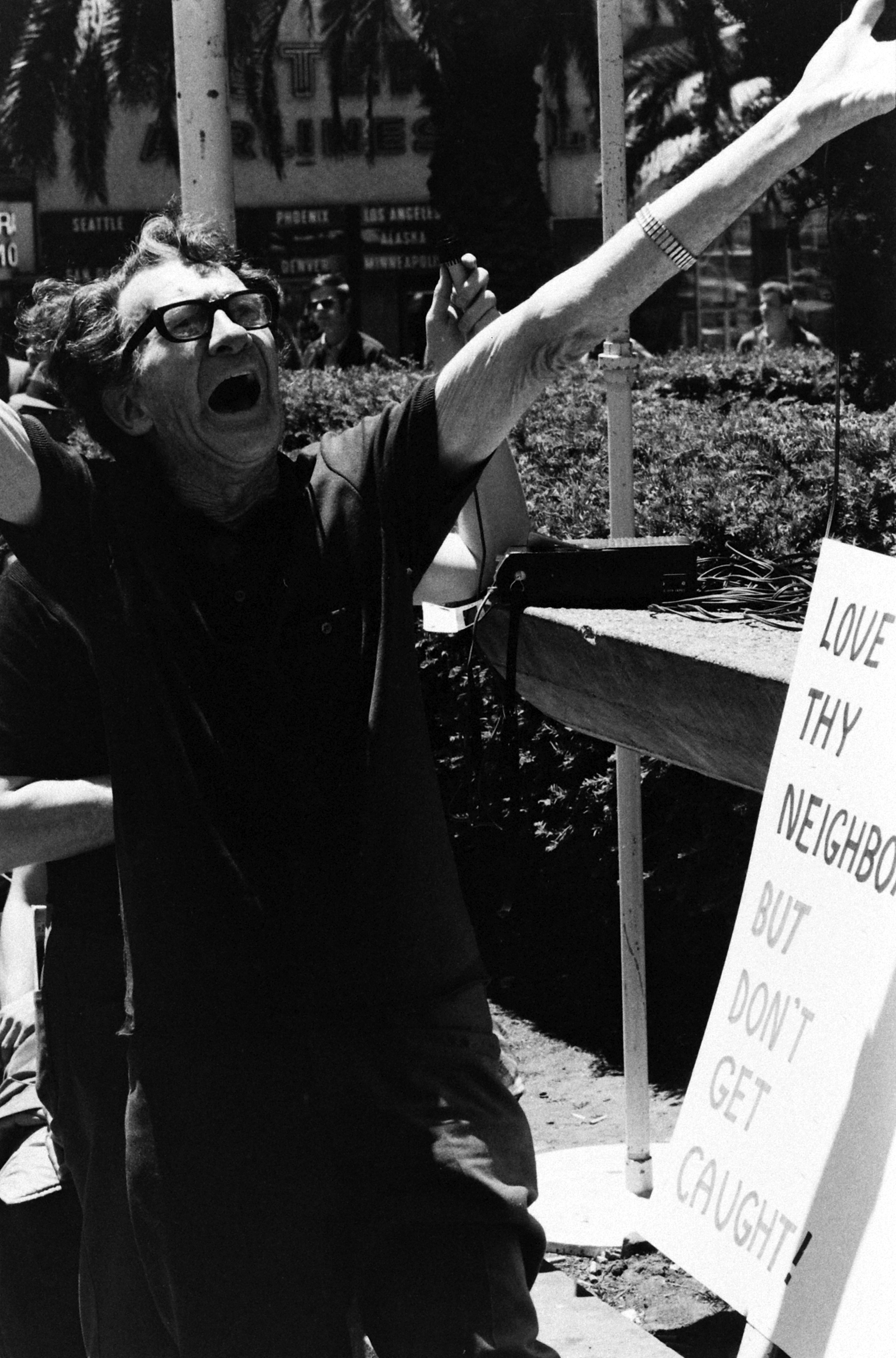

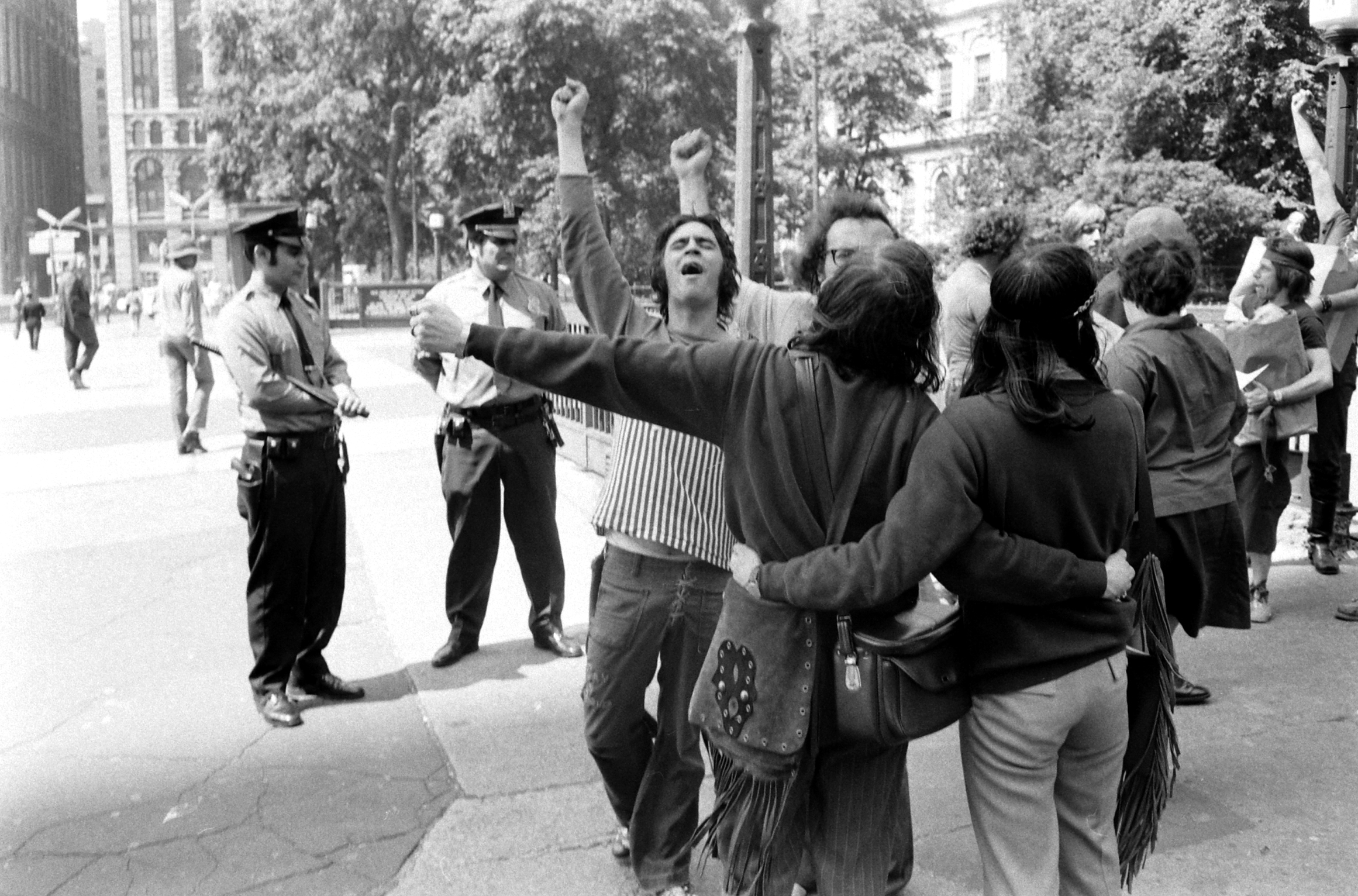

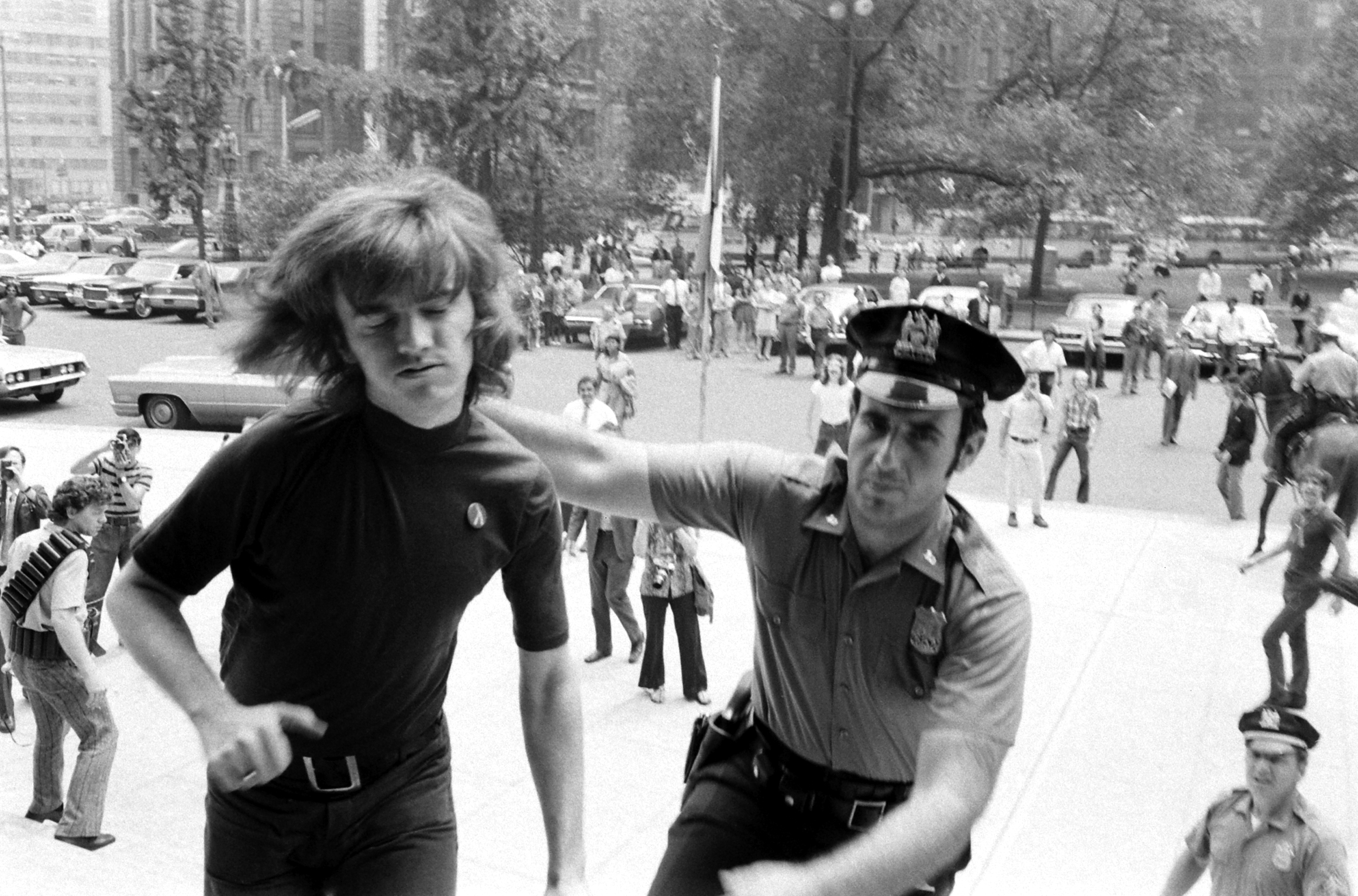

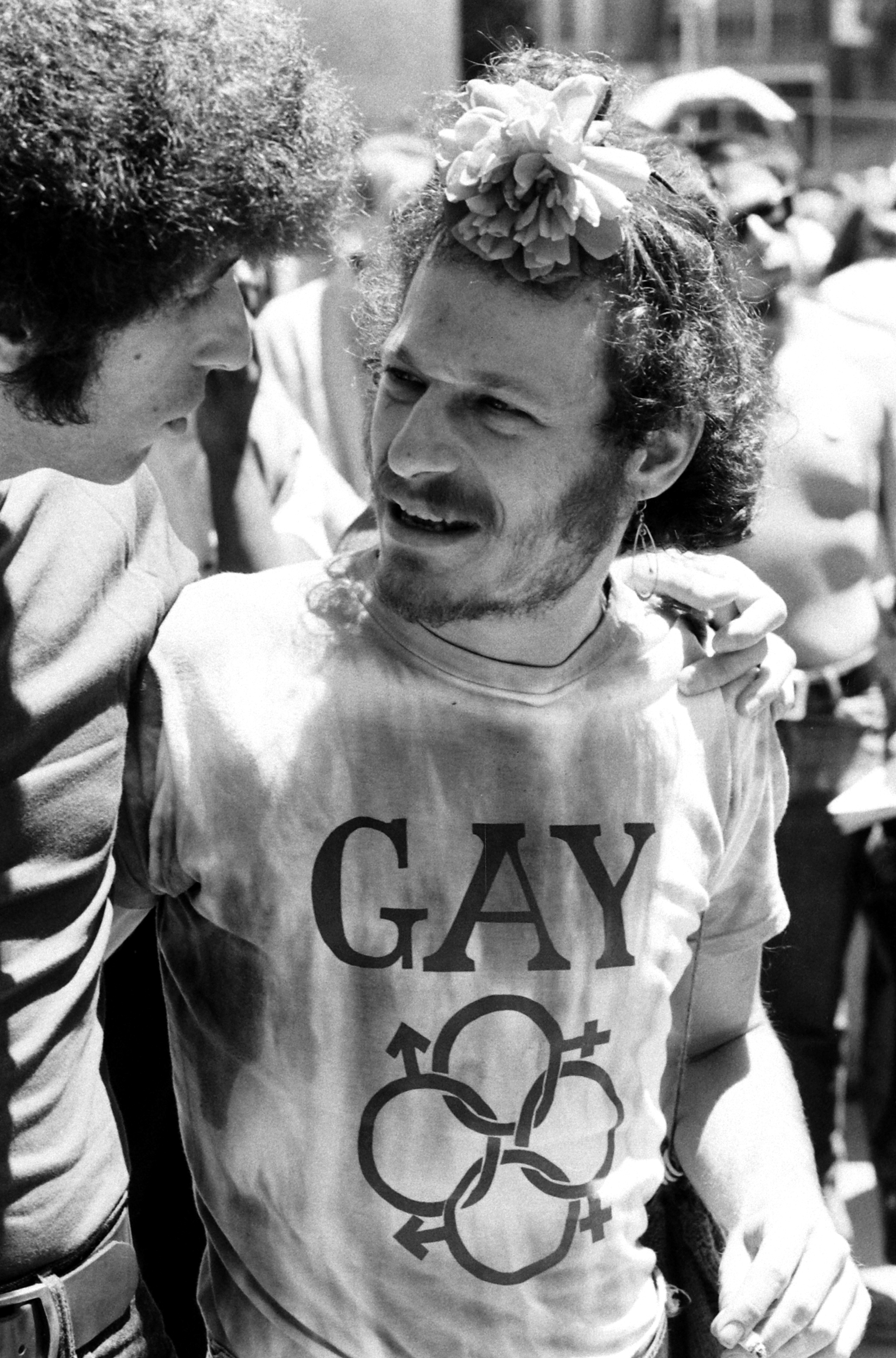

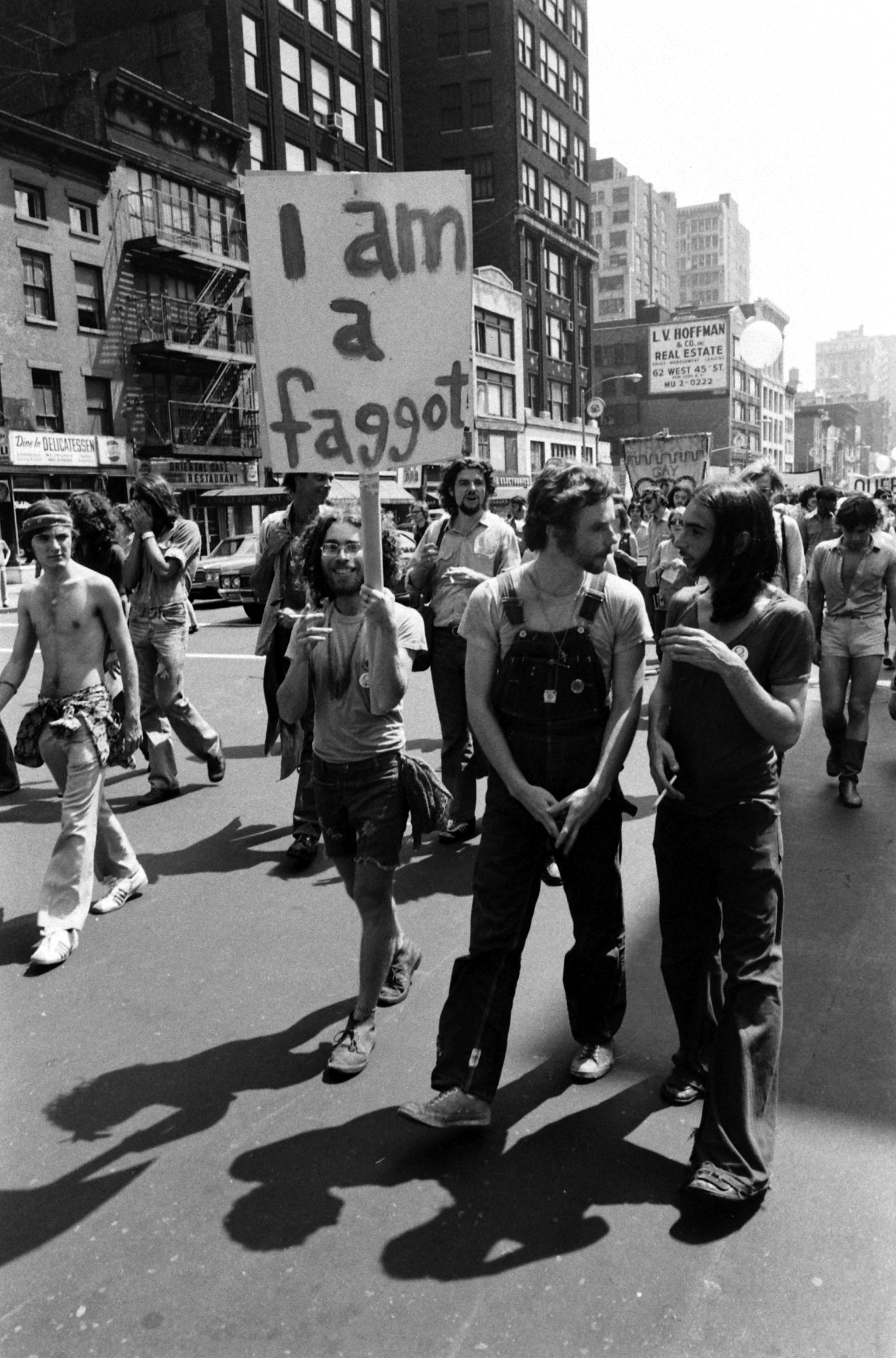

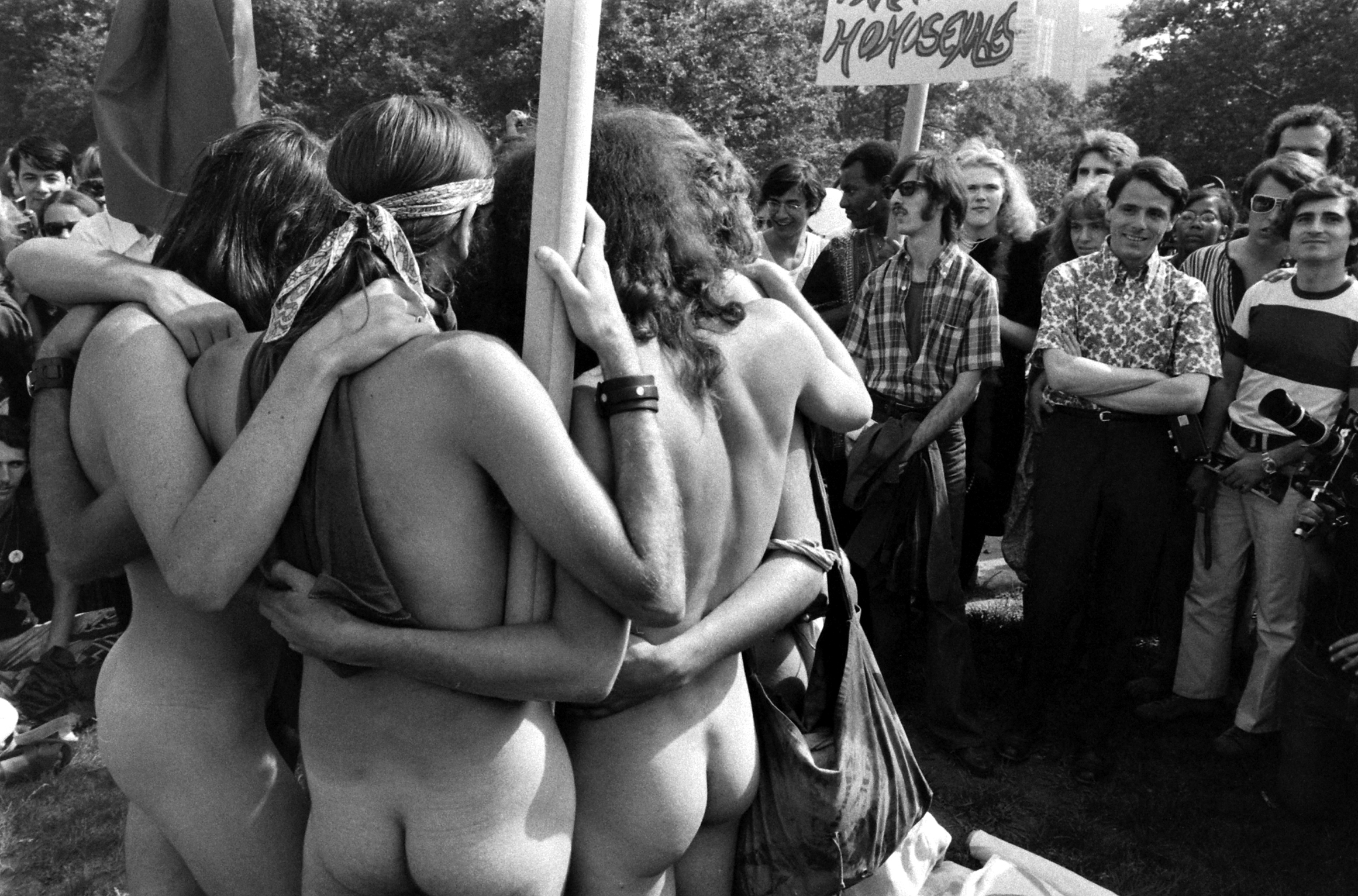

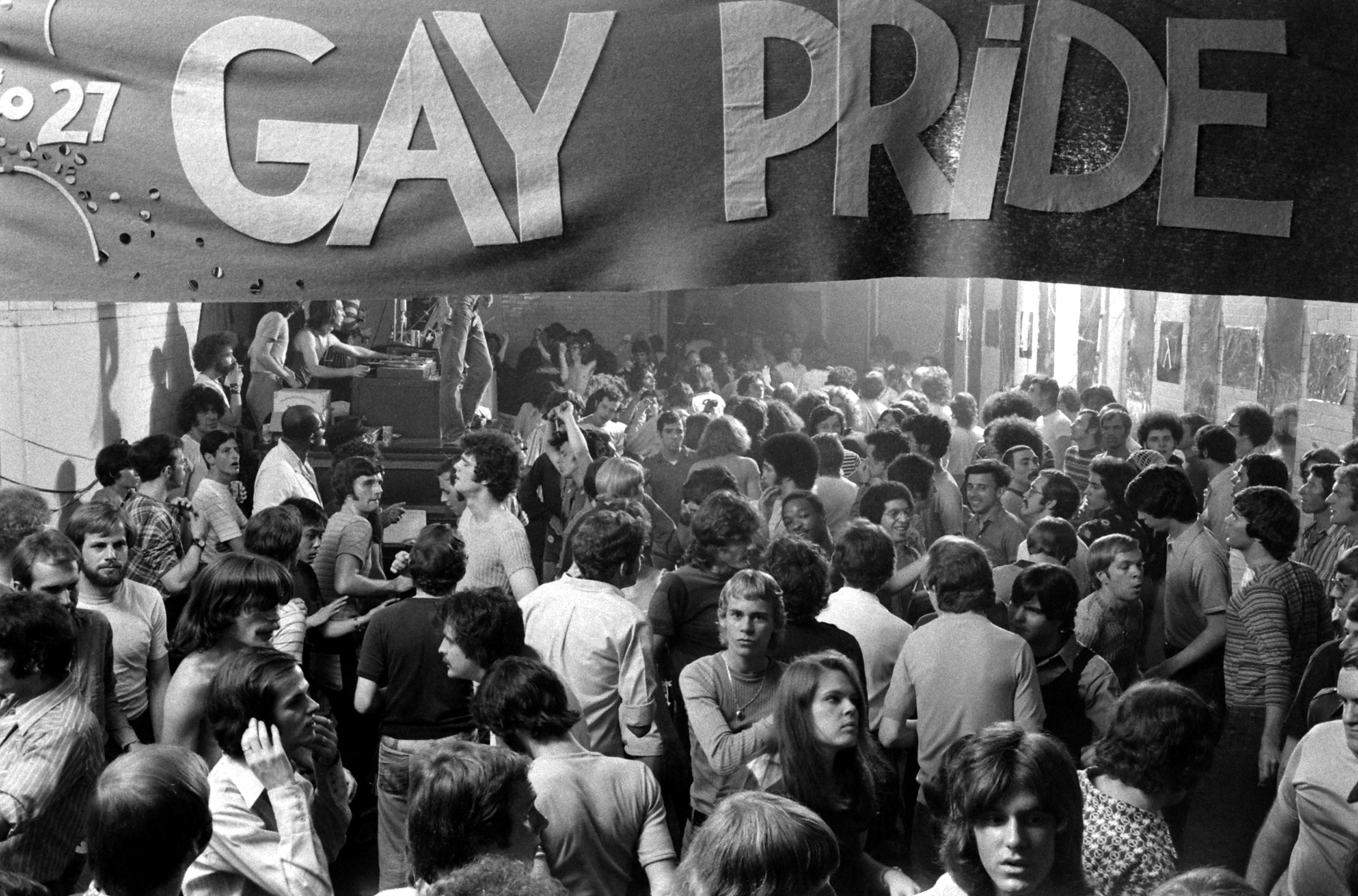

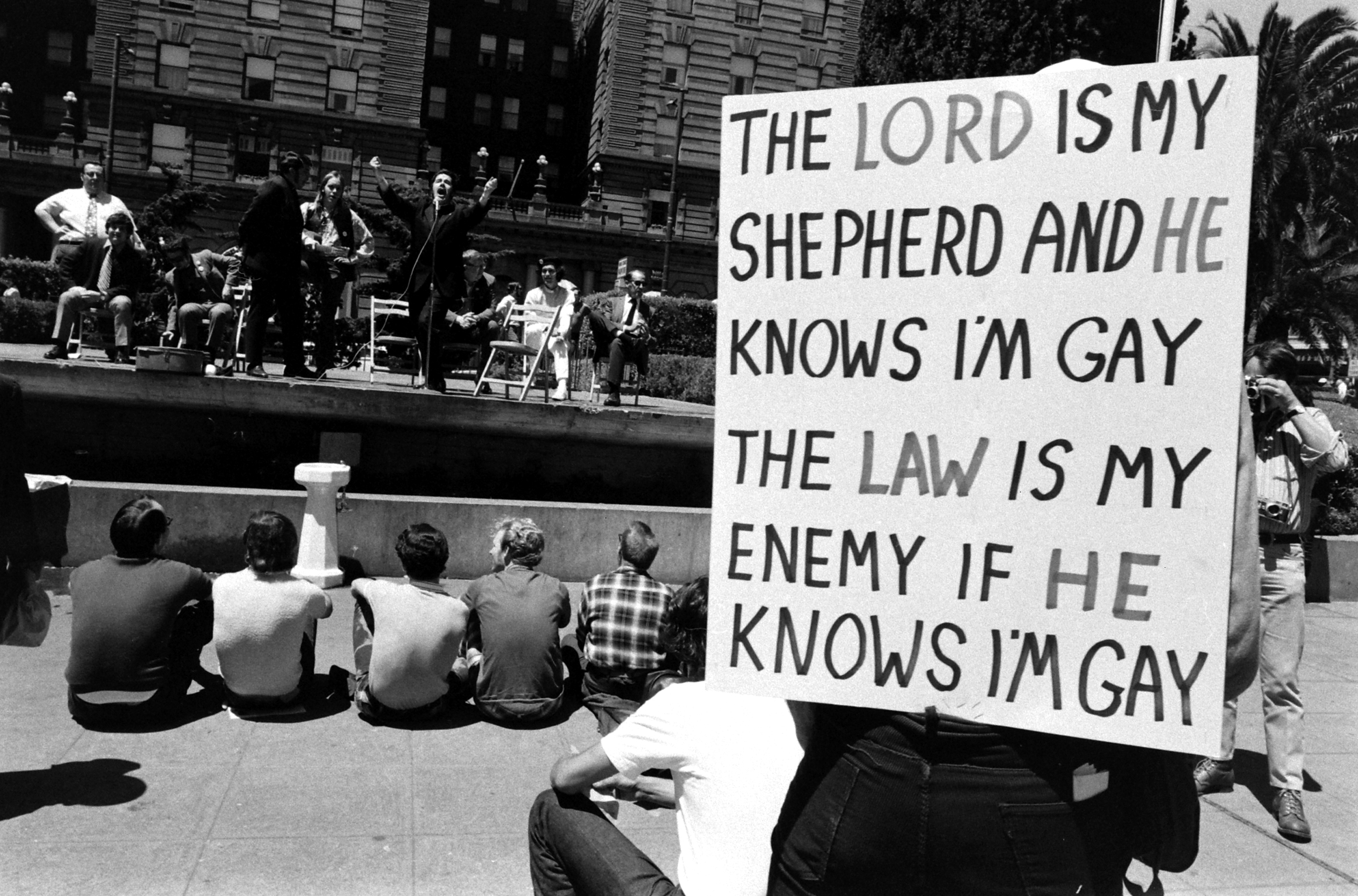

Silent No More: Early Days in the Fight for Gay Rights

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com