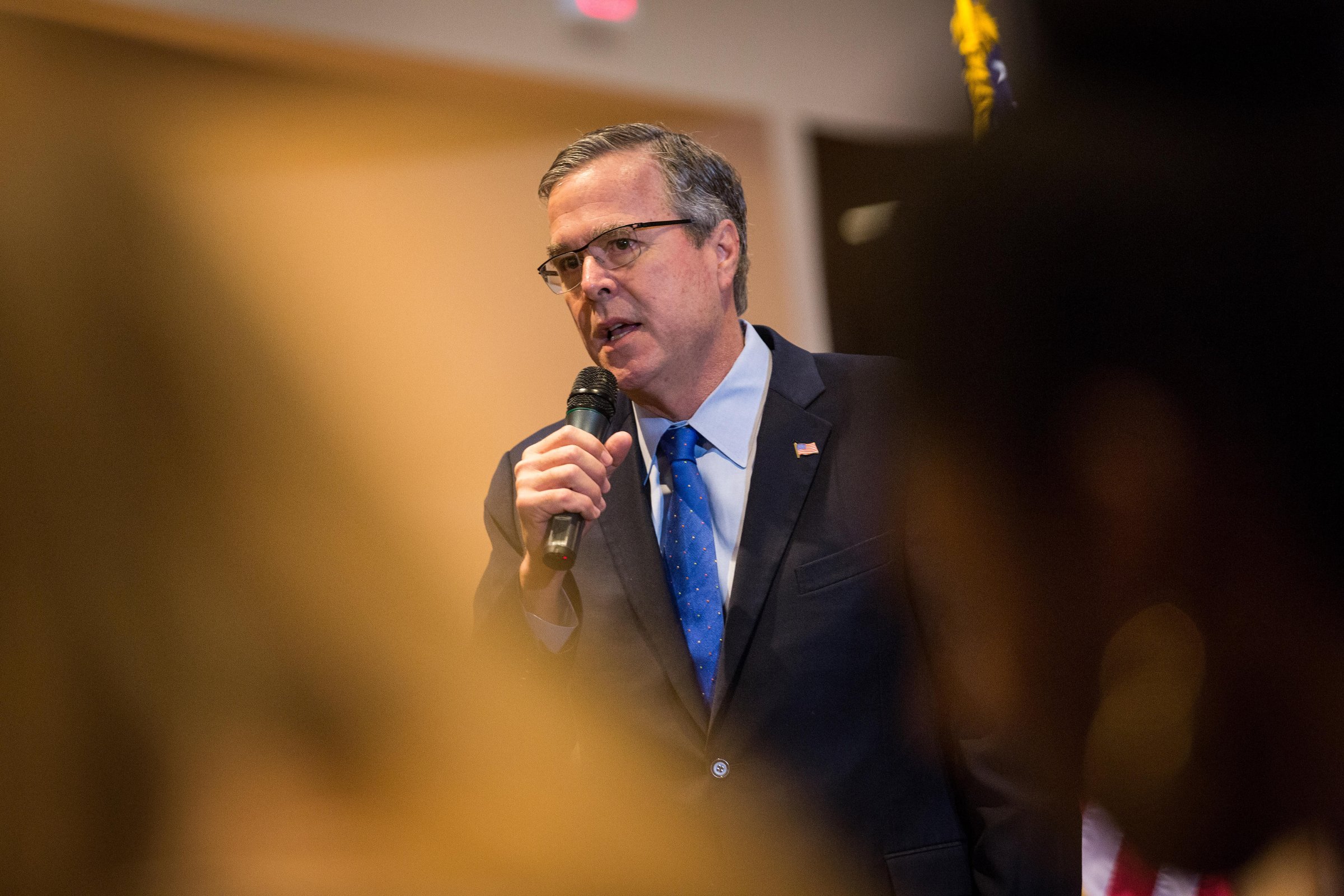

Shortly after he was sworn in as governor in 1999, Jeb Bush signed a union-backed bill that some argue led Florida’s cities to massively underfund their municipal pensions. As he squares off against Wisconsin Gov. Scott Walker and others in the Republican presidential primary, the law may come to haunt him.

“If you’re Governor Walker, you can say ‘I took on the unions, while he gave them what they wanted,’” said Andrew Biggs, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think tank. “It plays as something where he held the line, and Governor Bush didn’t.”

The law set a minimum standard for fire and police pension benefits and used state money to encourage cities to enhance pensions above those amounts. The goal was to increase pension benefits without letting cities simply pass their baseline obligations onto the state.

During the boom years of the early 2000s, the system worked well. But when the Florida economy crashed in 2008, the law prevented cities from getting help from the state to cover their pension losses. Instead, to avoid leaving state money on the table, cities ended up continuing to add extra benefits, leaving local taxpayers on the hook for the core of the pensions and increasing government spending overall.

“Now you have a hole in your underlying funding,” explains Mike Sittig, president of the Florida League of Cities. “That hole has to be filled, and in most cities that hole is filled with property taxes. It means that property taxes went up, or some other local priority was cut out of the budget.”

In the 16 years since the law was passed, pension spending has skyrocketed as some cities have tried to make up for pension fund losses in the market. A bill to reform the 1999 law passed the Florida legislature on April 24th — it ends the rule that state funds only be used for extra pension benefits, but incentivizes cities and unions to directly negotiate on the municipal level. That bill is awaiting Governor Rick Scott’s signature, but the damage may already be done. A 2014 report card of Florida municipal pensions conducted by the Leroy Collins Institute and Florida TaxWatch found that almost 50% of municipal pension plans got “D” or “F” grades.

Police and firefighter unions stood by the 1999 law as a way to ensure that first responders get their due, regardless of a city’s budget problems. “That’s not the police officer’s fault, that’s not the union’s fault, that’s the fault of city leaders who did not put in the money that they should have,” says John Rivera, president of the Florida Police Benevolent Association. But both unions also support the recently passed legislation.

Gov. Bush’s campaign team says the economic problems are the fault of the cities’ mismanagement, not the law itself. “The intent was always that these benefits be funded in a fiscally sound way,” says Kristy Campbell, a Bush spokeswoman. “Some cities did not.” She added that the candidate supports the recent reform, noting that it’s “consistent with the original purpose and intent of the 1999 law,” which she says was to ensure that funding for benefits was “fiscally sound.”

Opponents to the law have been trying to raise awareness about the $10 billion unfunded liability in Florida municipal pensions. Florida TaxWatch, a research institute and government watchdog, has even started a coalition called Taxpayers for Sustainable Pensions to explain the problem and encourage reform.

So far, the pension issue has not become a major rallying cry in the Sunshine State, and none of the other 2016 Republican hopefuls have picked it up as an attack line. But it could become a headache for Bush if the race narrows with Walker, who defeated public-sector unions in a high-profile fight that avoided any cuts to police or fire employee pensions in Wisconsin.

“You’ve got pension funding problems in almost every state in the country, so that’s something that can resonate with people,” Biggs says. “If you work out how generous public employee pensions are compared to what you or I are going to get in a 401(k) … it looks like a giveaway to a group that is already getting a better pension than you or me.”

The pension problem is ultimately the local government’s responsibility, though critics blame unions’ role in state politics for exacerbating it.

“Jeb Bush likely credited them for his victory in ’99, and this was the reward,” says state Sen. Jeremy Ring, a Democrat who sponsored the recent reform bill. “It was the most union-friendly bill I’ve ever seen.”

The pension drama has the potential to cast a cloud on Bush’s claims that during his time in the governor’s mansion he was the “most conservative governor in the country.” While he cut billions in taxes and balanced the state’s budget, he did so at a time of strong economic growth. When the market collapsed a year after he left office, many of the gains under his tenure eroded. Critics contend Bush should have pursued policies that would have been more resilient during a downturn.

Many of the Floridians who opposed the bill in the 1990s say that the law has done exactly what they feared it would. Tallahassee City Commissioner Scott Maddox’s father was the first president of the Florida police union, but the younger Maddox fought against the bill when he was Tallahassee mayor in 1999. “It keeps adding to that benefit, even if it wasn’t asked for,” he says. “It makes no sense to me.”

“I’m for local control, and I’m for collective bargaining, and I’m fiscally conservative,”says Maddox, a Democrat who also served as President of the Florida League of Cities. “If you’re any of those three things, I don’t know how you can support that legislation.”

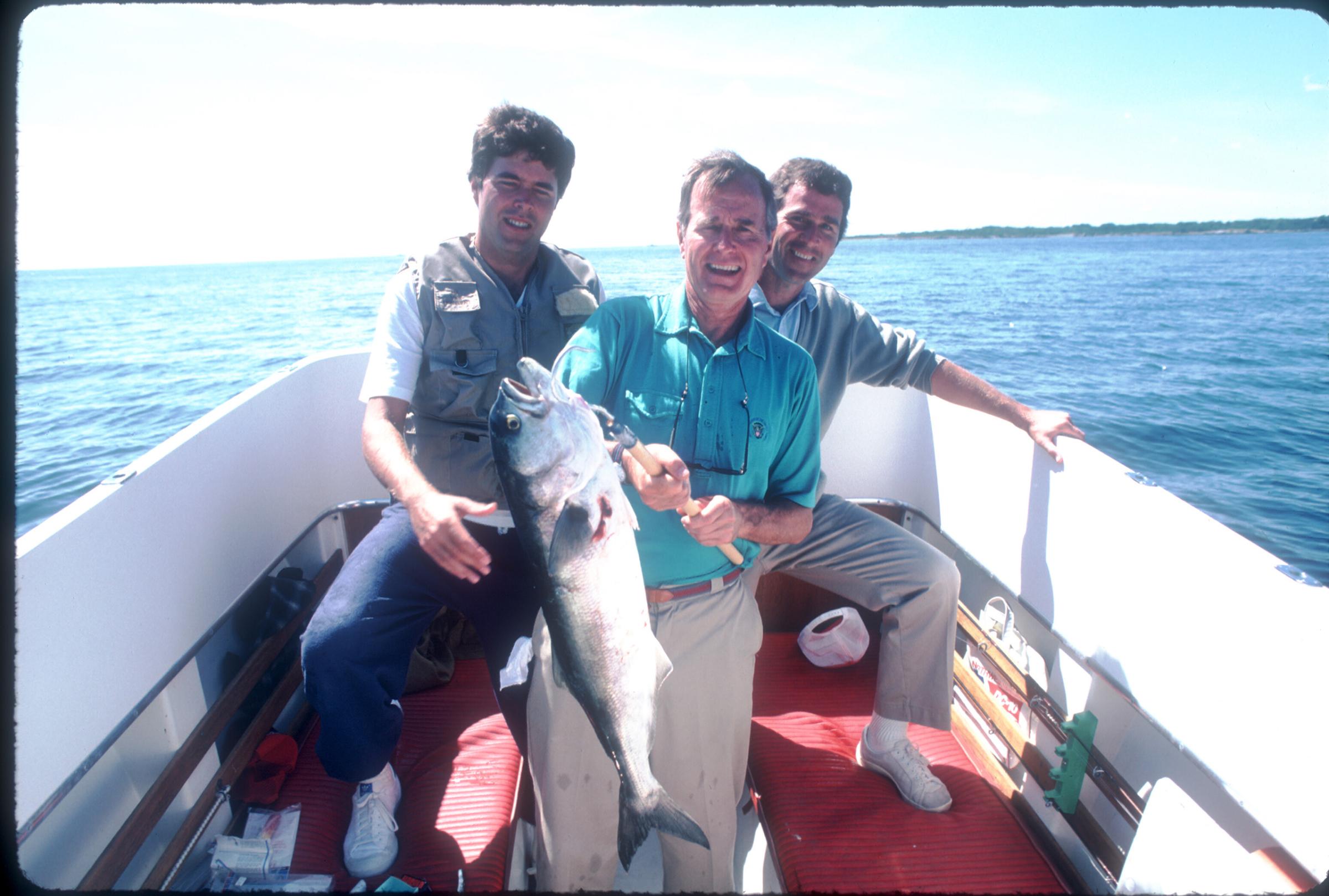

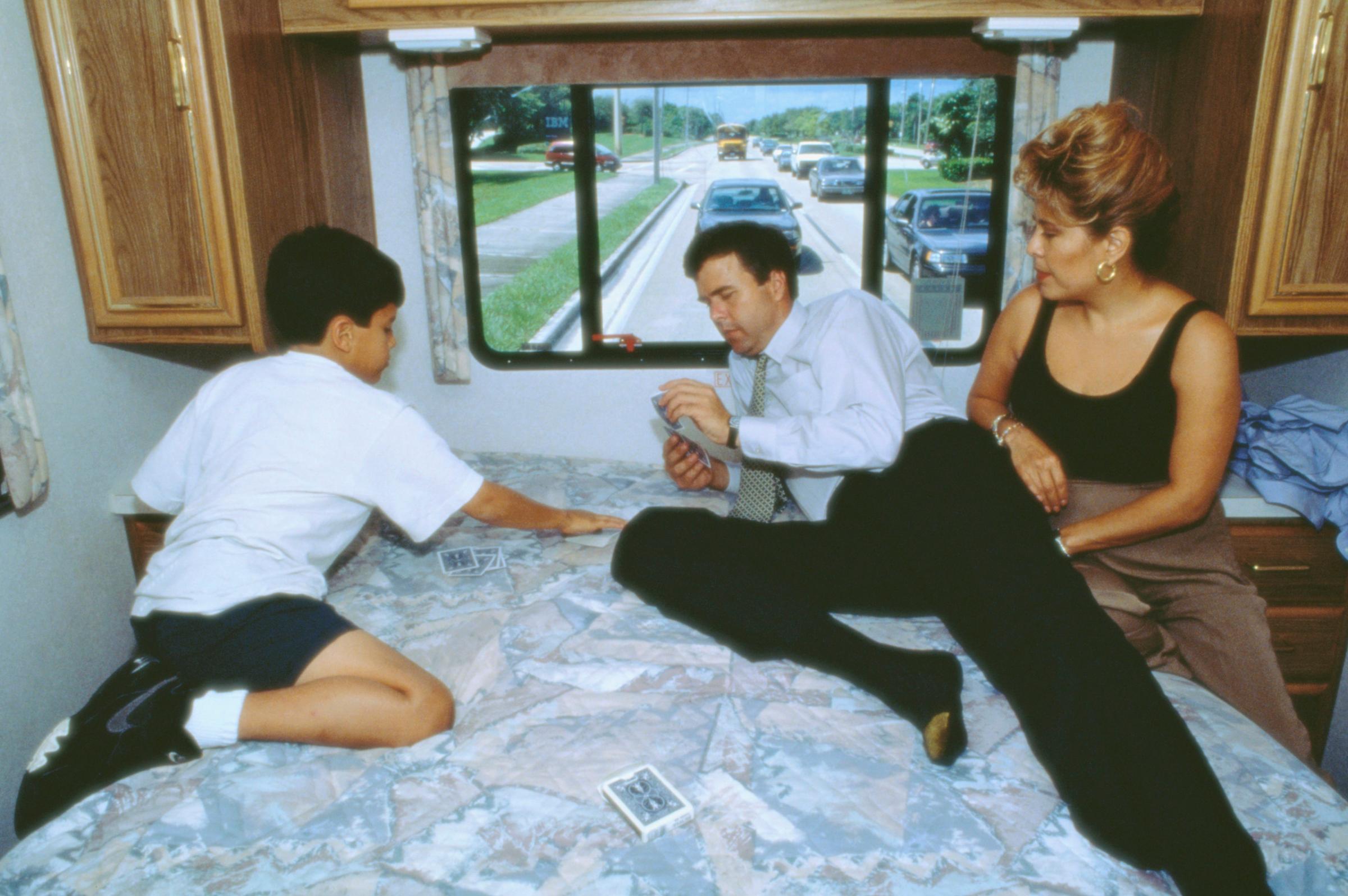

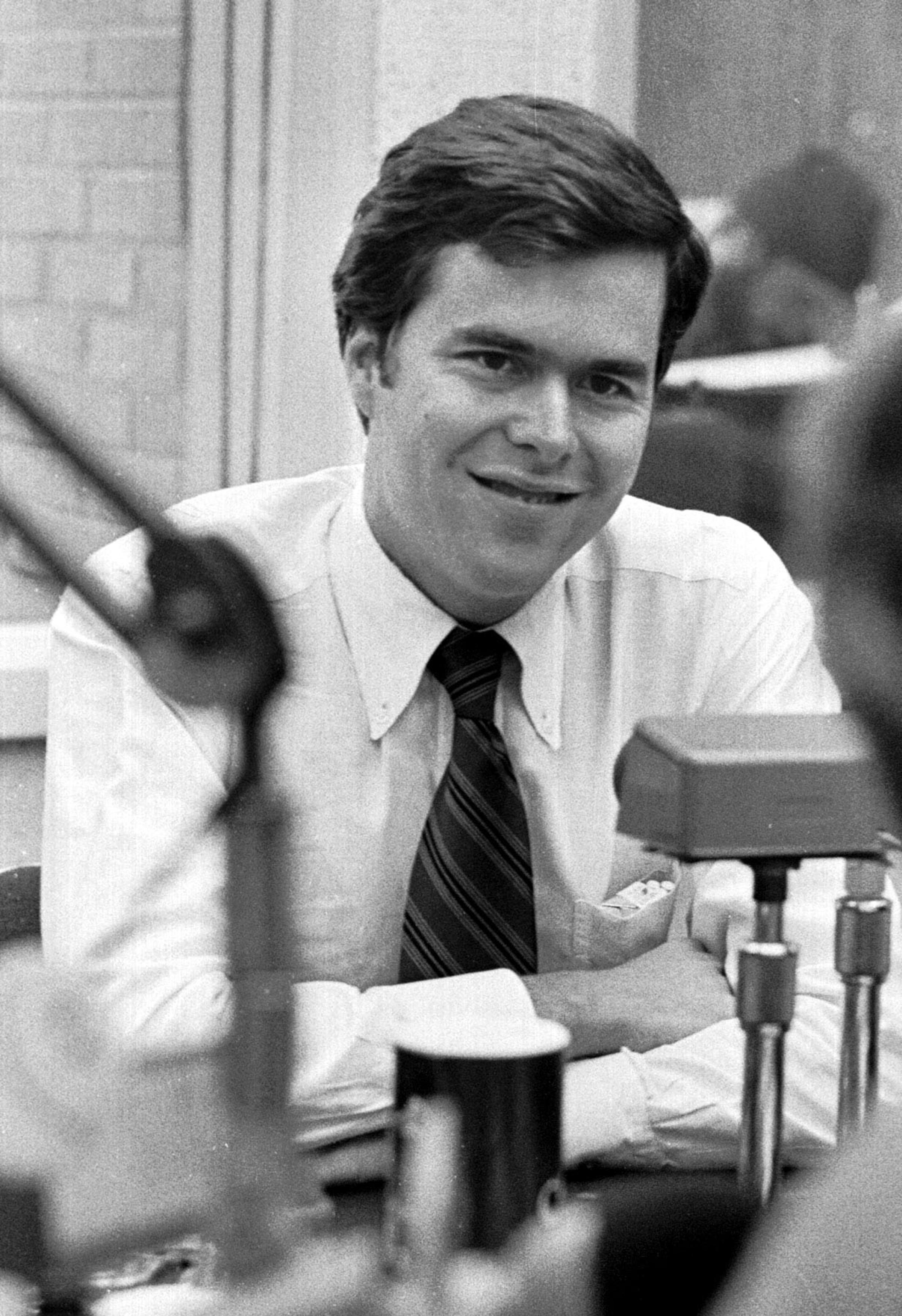

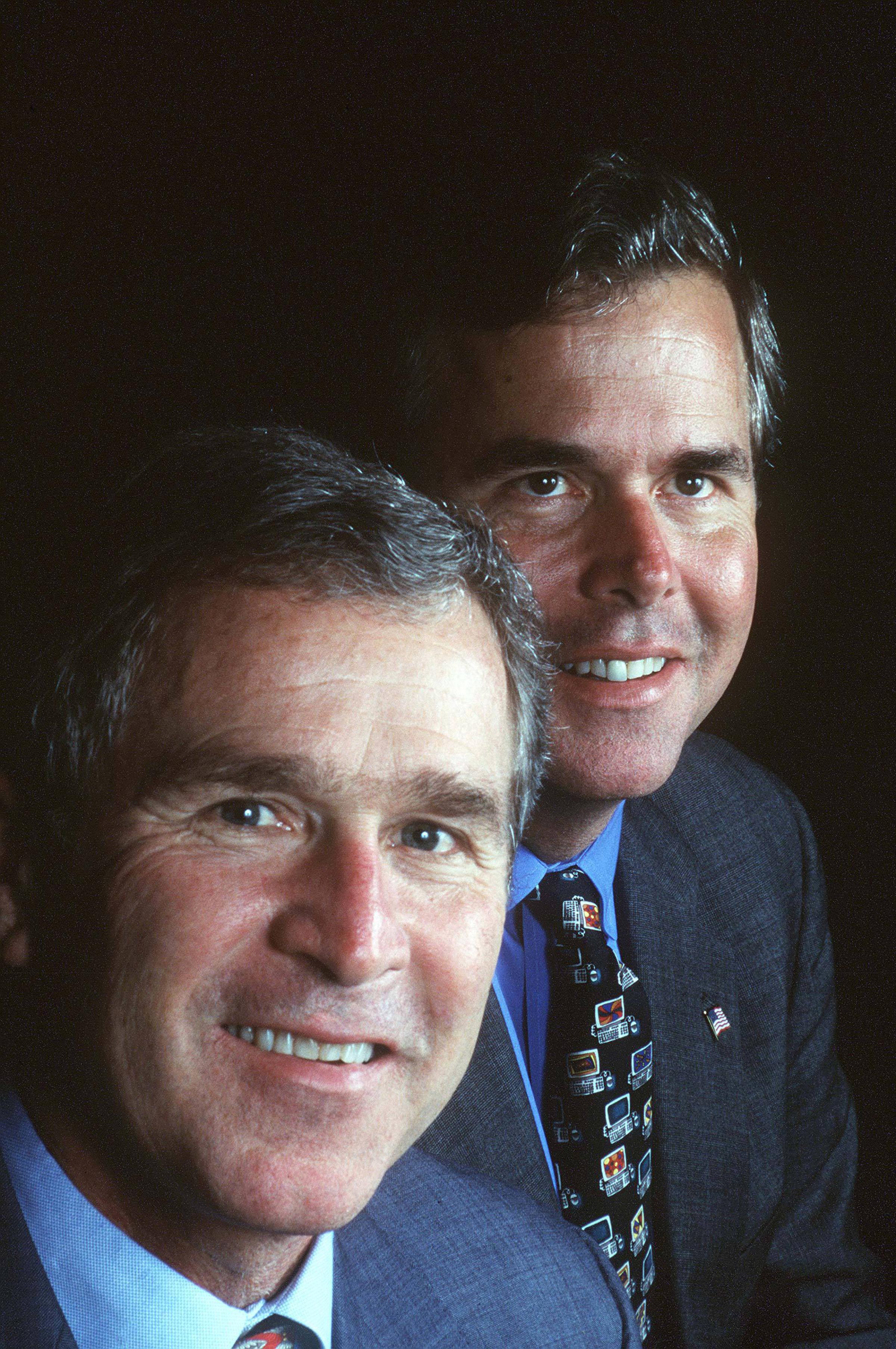

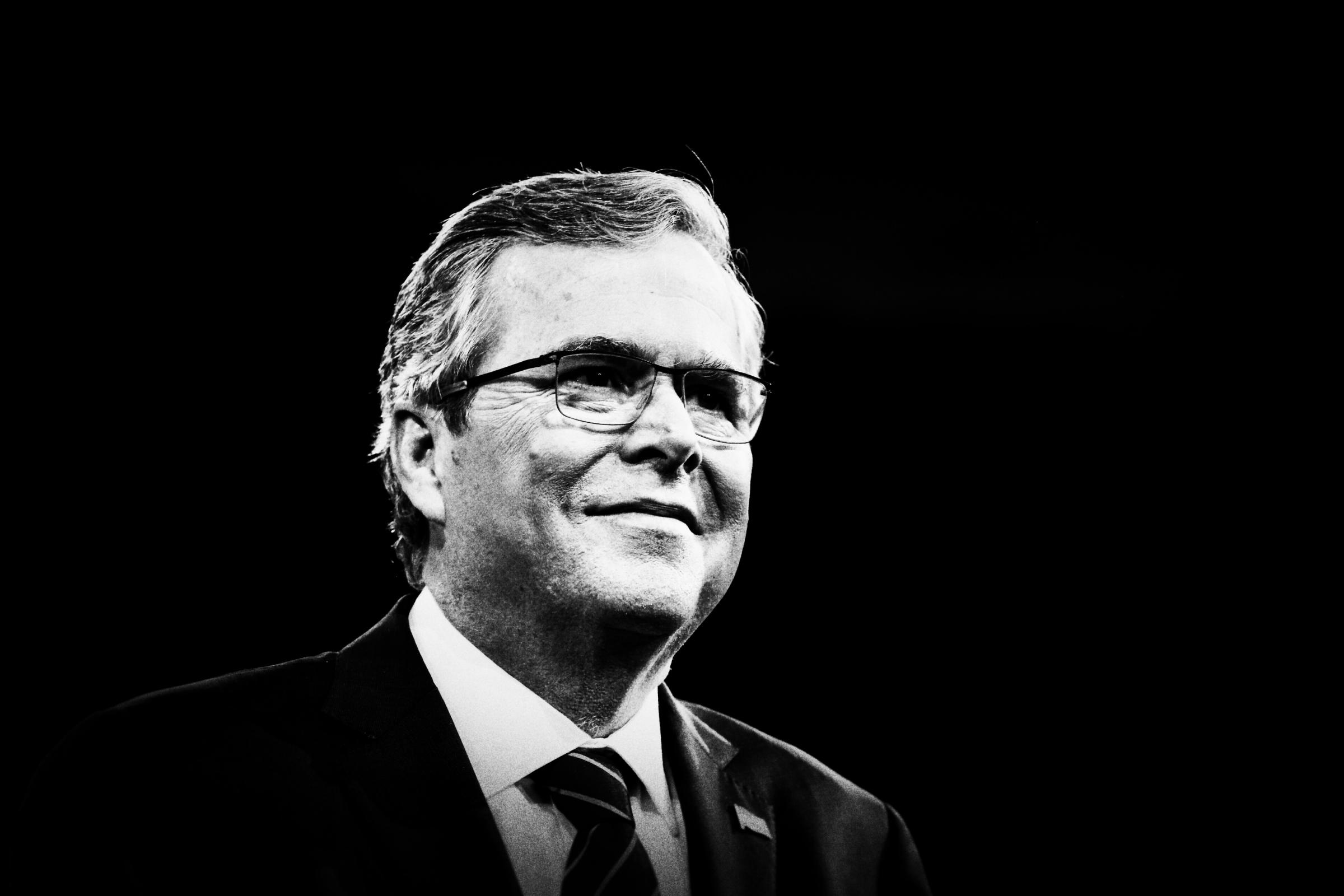

See Jeb Bush's Life in Photos

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Charlotte Alter at charlotte.alter@time.com