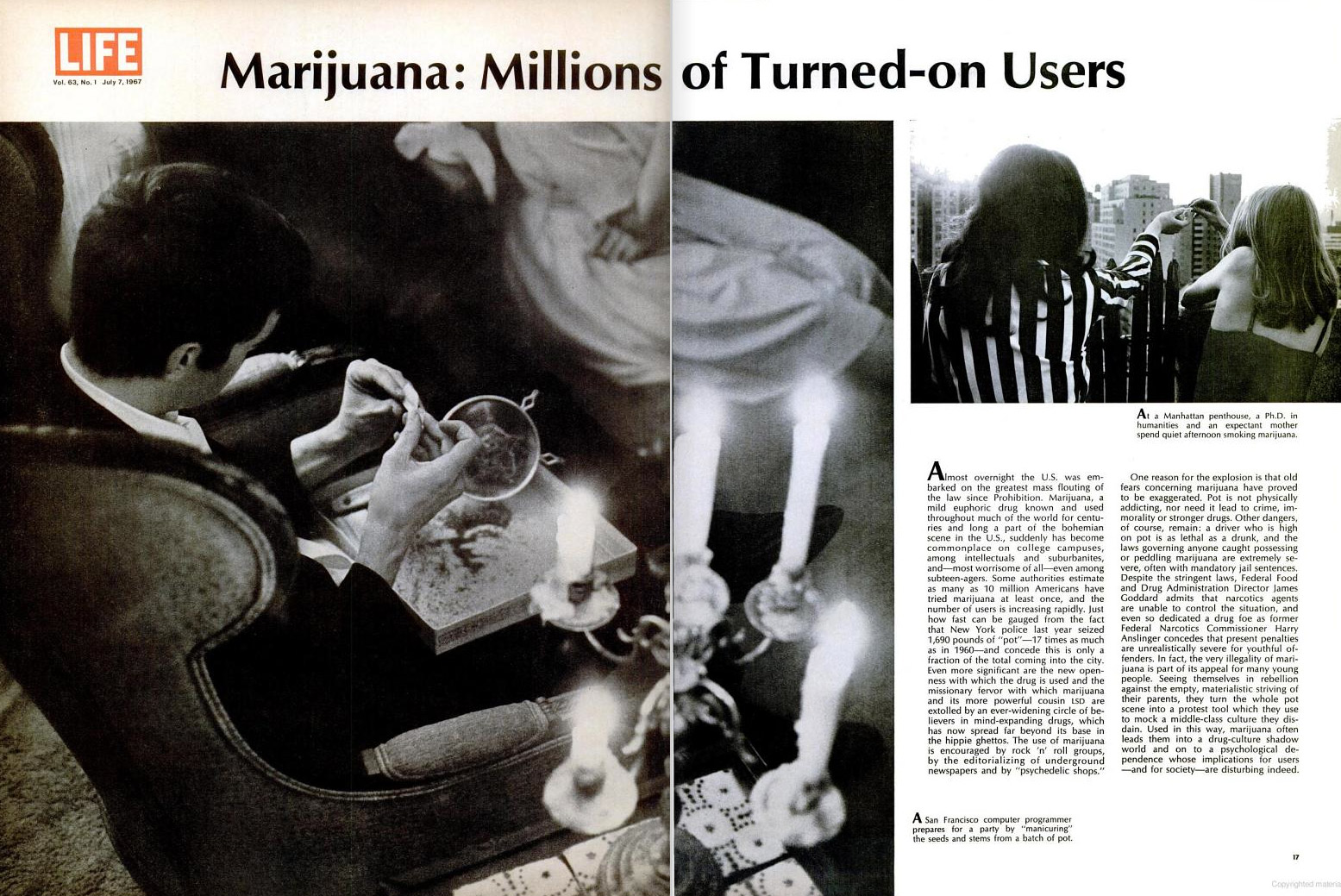

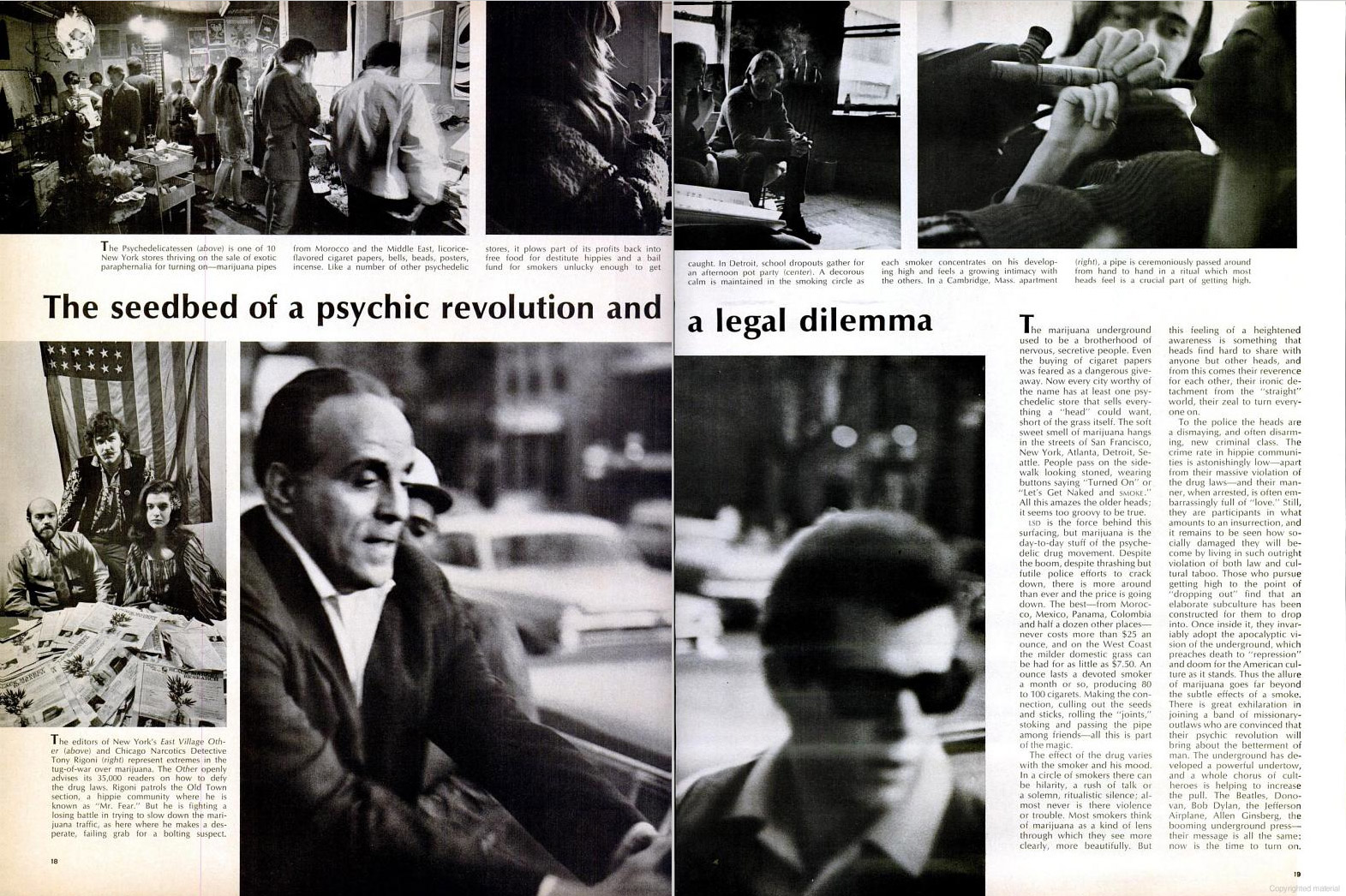

“The soft sweet smell of marijuana hangs in the streets of San Francisco, New York, Atlanta, Detroit, Seattle. People pass on the sidewalk looking stoned, wearing buttons saying ‘Turned On’ or ‘Let’s Get Naked and SMOKE.’” So LIFE Magazine described a cultural moment in which pot seemed to be taking over: readily available, encouraged by popular music, not merely a drug but the symbol of a revolution.

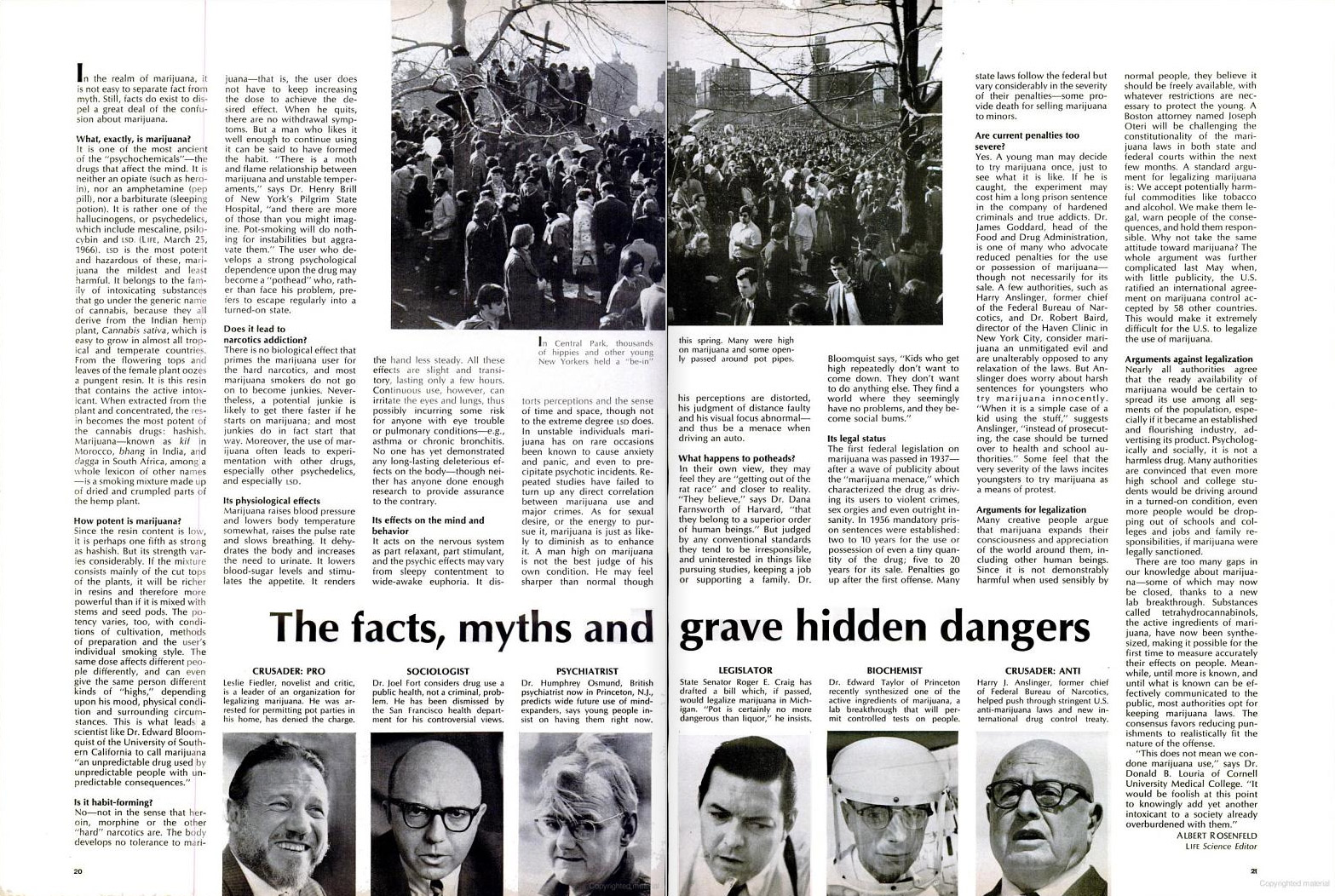

Some of the arguments for and against its legalization were not so different in the late 1960s than they are today. Opponents viewed the drug not only as a public health concern, but as the flag the counter-culture waved in the face of middle class values and consumer culture. They feared that use was already spiraling out of control and would only increase with legalization. They envisioned a generation of dropouts—from school, from family responsibilities, from society at large—derailed by a drug whose effects were not yet fully understood by the medical community.

Those in favor held marijuana up against alcohol and tobacco, which they said were no more harmful. They pointed to low crime rates among users, aside from the laws they broke by partaking in the first place. They celebrated the drug’s boost to creativity, consciousness and appreciation for the world. Even the former Federal Narcotics Commissioner conceded that penalties were “unrealistically severe for youthful offenders.”

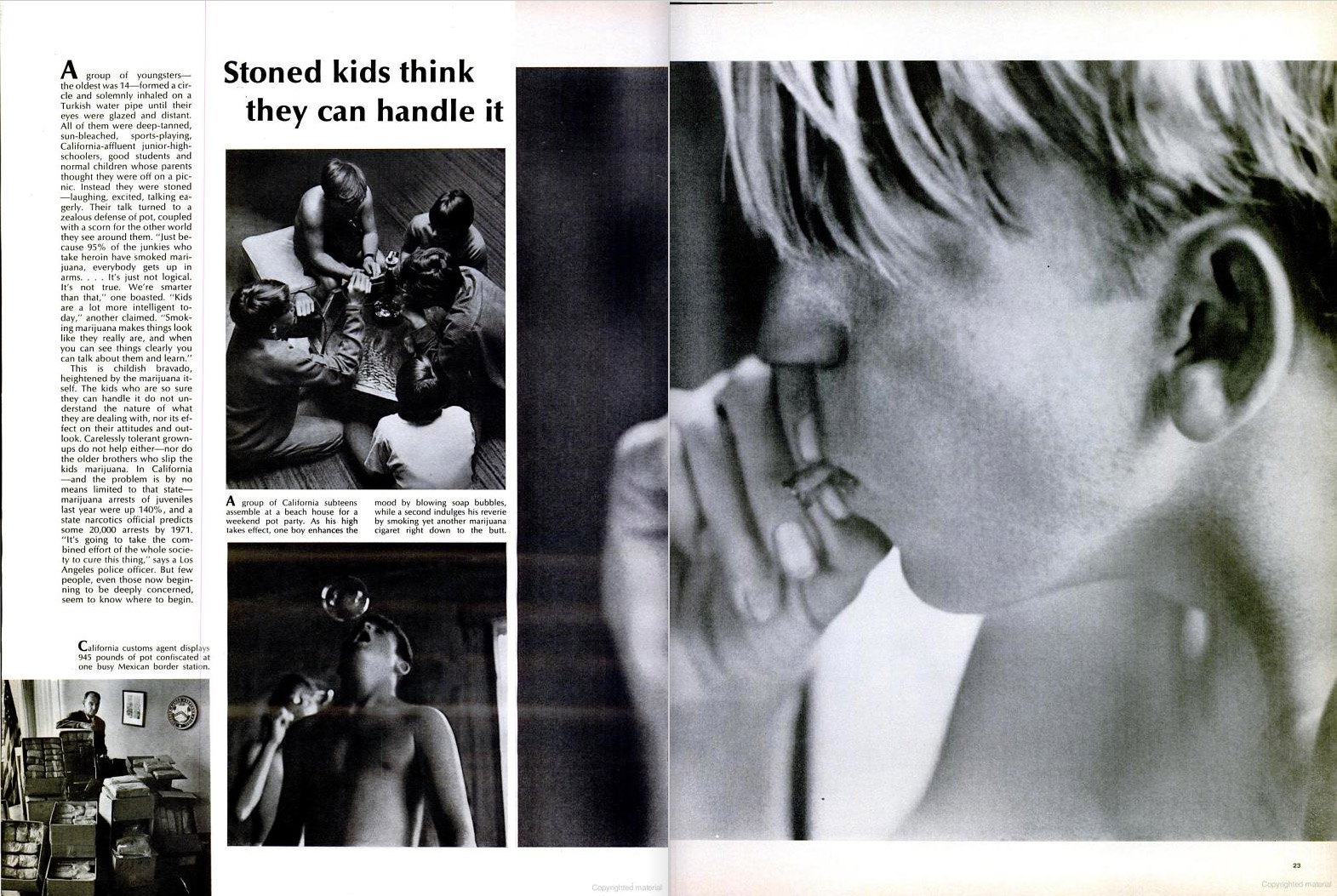

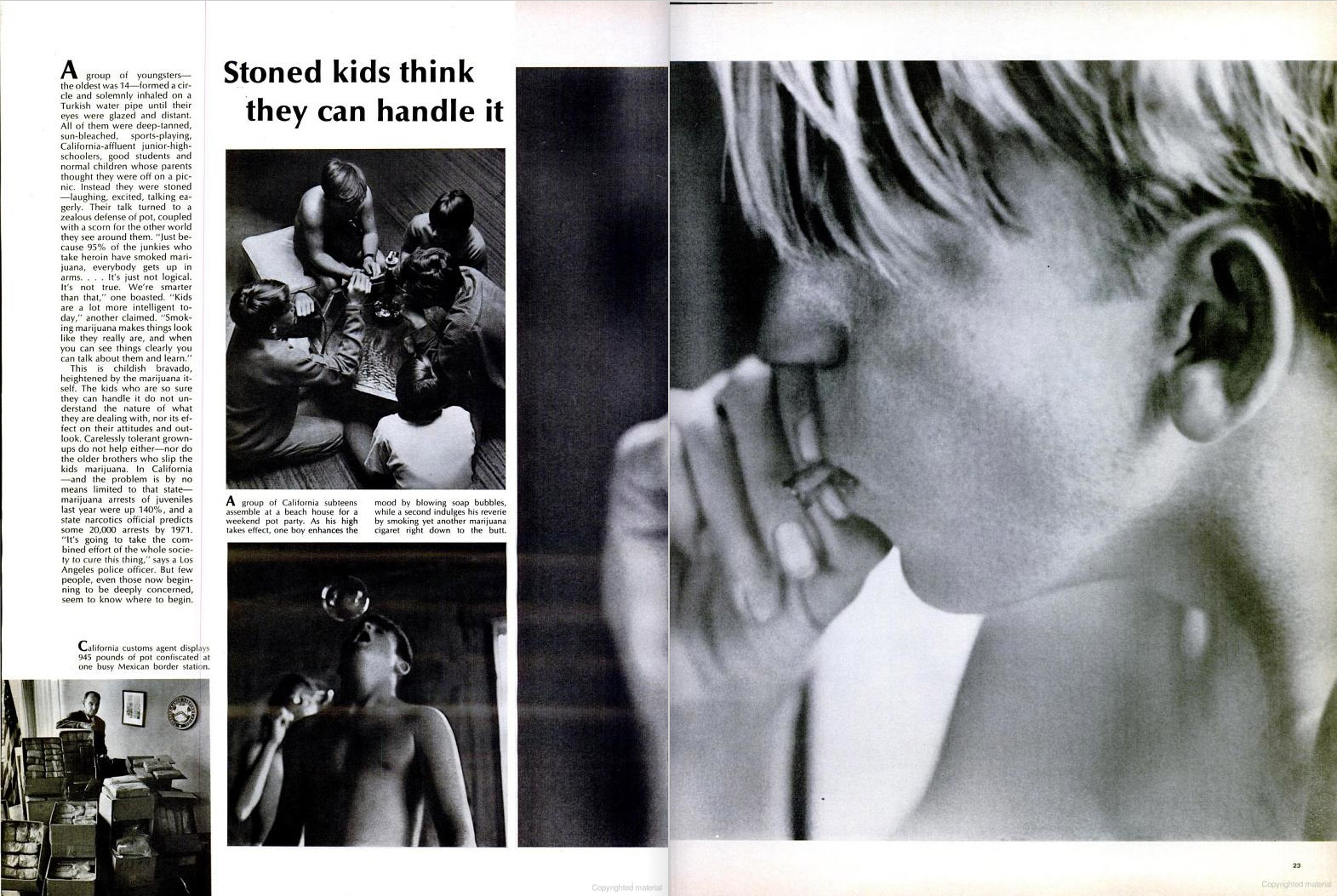

These youthful offenders were of utmost concern, and LIFE featured a group of “subteen-agers” (1960s speak for “tweens”) to show why. The affluent Californian kids, none older than 14, were described as “good students and normal children whose parents thought they were on a picnic.” Youth arrests were on the rise, and many feared that lenient parents and the influence of older siblings were turning a generation onto something they weren’t equipped to handle.

Looking toward the future, LIFE wondered how users would fare. “It remains to be seen how socially damaged they will become by living in such outright violation of both law and cultural taboo.” It’s a sentiment that today feels either comically outdated or pertinent as ever, depending on which side of the debate one comes down on.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Biden Dropped Out

- Ukraine’s Plan to Survive Trump

- The Rise of a New Kind of Parenting Guru

- The Chaos and Commotion of the RNC in Photos

- Why We All Have a Stake in Twisters’ Success

- 8 Eating Habits That Actually Improve Your Sleep

- Welcome to the Noah Lyles Olympics

- Get Our Paris Olympics Newsletter in Your Inbox

Write to Eliza Berman at eliza.berman@time.com