Throughout the trial of Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, the 21-year-old who was convicted last week of bombing the Boston Marathon in 2013, his family resisted the urge to speak out publicly in his defense. Tsarnaev’s defense team had advised them not to grant interviews, they say, as it could risk his chances at trial. But when the jury issued its guilty verdict on April 8, convicting him on 17 counts that could each carry the death penalty, some of his relatives decided to go public with their outrage.

On the evening of April 14, three members of the Tsarnaev family met at a café in the city of Grozny, close to their ancestral home in southern Russia, and told a TIME reporter how the trial had torn their family apart, how helpless they felt against what they see as an American conspiracy against them and, above all, how they still hope to convince Tsarnaev to fire his legal team and seek to overturn the verdict on appeal.

“It would be so much easier if he had actually committed these crimes,” says his aunt Maret Tsarnaeva. “Then we could swallow this pain and accept it.”

But two years after the bombing that killed three people and wounded hundreds near the race’s finish line on April 15, 2013, they still refuse to admit Tsarnaev’s guilt. From their homes in Chechnya and Dagestan, two predominantly Muslim regions of Russia, some of his family members have tried to convince Tsarnaev to fire his court-appointed lawyer, Judy Clarke, who has taken a surprising approach to his defense.

In one of her first arguments before the jury after entering a not-guilty plea, Clarke said that her client is indeed responsible for the “senseless, horrific, misguided acts.” But in committing these crimes, she argued that he was acting under the direction of his older brother Tamerlan, who was killed in a shootout with authorities soon after the bombing.

This line of defense has outraged many of Tsarnaev’s relatives, who have tried to convince him to dismiss Clarke and ask for a lawyer who will argue his innocence. “Why do we even need defense attorneys if they just tell the jury he is guilty?” his aunt asks. “What’s the point?”

Like many observers of the case in Russia, the Tsarnaev family has claimed — without providing any meaningful evidence — that the bombing was part of a U.S. government conspiracy intended to test the American public’s reaction to a terrorist threat and the imposition of martial law in a U.S. city. “This was all fabricated by the American special services,” Said-Hussein Tsarnaev, the convicted bomber’s uncle, tells TIME. A panel of 12 jurors in Boston reached the verdict after weeks of testimony from some 90 witnesses and 11 hours of deliberations spread over two days.

Tsarnaev’s mother, Zubeidat, made similar claims of a conspiracy soon after his arrest, but she seems to have come around since then to the strategy that her son’s lawyers have taken at trial. As a result, the family appears to have suffered a rancorous split. While the brothers’ paternal relatives, who spoke to TIME on Wednesday, have demanded a new legal team, their mother has refused to call for Clarke’s dismissal. “The mother won’t let us do it,” says Hava Tsarnaeva, the brothers’ great-aunt in Chechnya. “She won’t listen to reason.”

MORE Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Found Guilty on All Counts in Boston Bombing Trial

Their only real means of pressuring her is through Tsarnaev’s father, Anzor, a native of Chechnya who now lives in neighboring Dagestan. But he seems to have taken his wife’s side on the quality of their son’s defense. “As frightening as it is to admit, Anzor has been his wife’s zombie all his life, from the first day they met,” says his sister Maret.

In their desperation to reach Tsarnaev during the trial, his paternal relatives have tried sending letters, arranging phone calls and even encouraging a friend to go to the Boston courtroom and cry out to Tsarnaev during a hearing. But all of these efforts failed to reach him, they say, let alone convince him to fire his lawyers.

Their focus now has turned to outside help, primarily from rights activists and international institutions, though these efforts also have little chance of success. On Wednesday, they met with a leading rights activist in Chechnya, Heda Saratova, in the hope of filing an appeal in the case to the European Court of Human Rights. Saratova informed them that the U.S. is not a party to the court’s founding treaty, and therefore does not accept its jurisdiction.

On hearing the news, Maret Tsarnaeva, the aunt, let out a laugh through her tears. “So I guess the U.S. has really proven its exceptionalism in this case,” she says, bitterly. “It’s a closed circle.” And it leaves his family no choice but to wait for April 21, when the sentencing phase of the trial will consider whether Tsarnaev should face the death penalty or spend the rest of his life in prison.

Read next: Dzhokhar Tsarnaev Probably Won’t End Up in Massachusetts

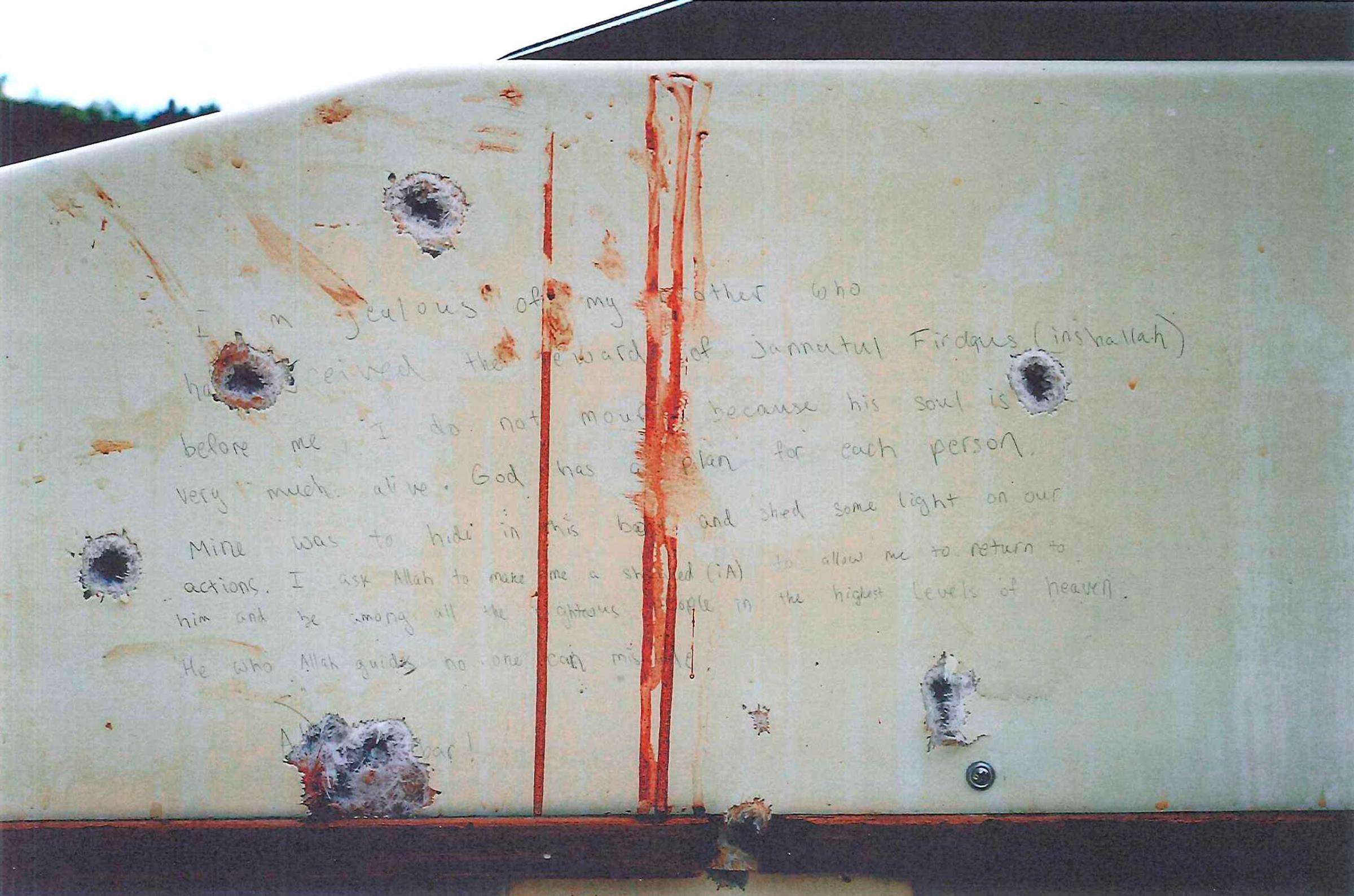

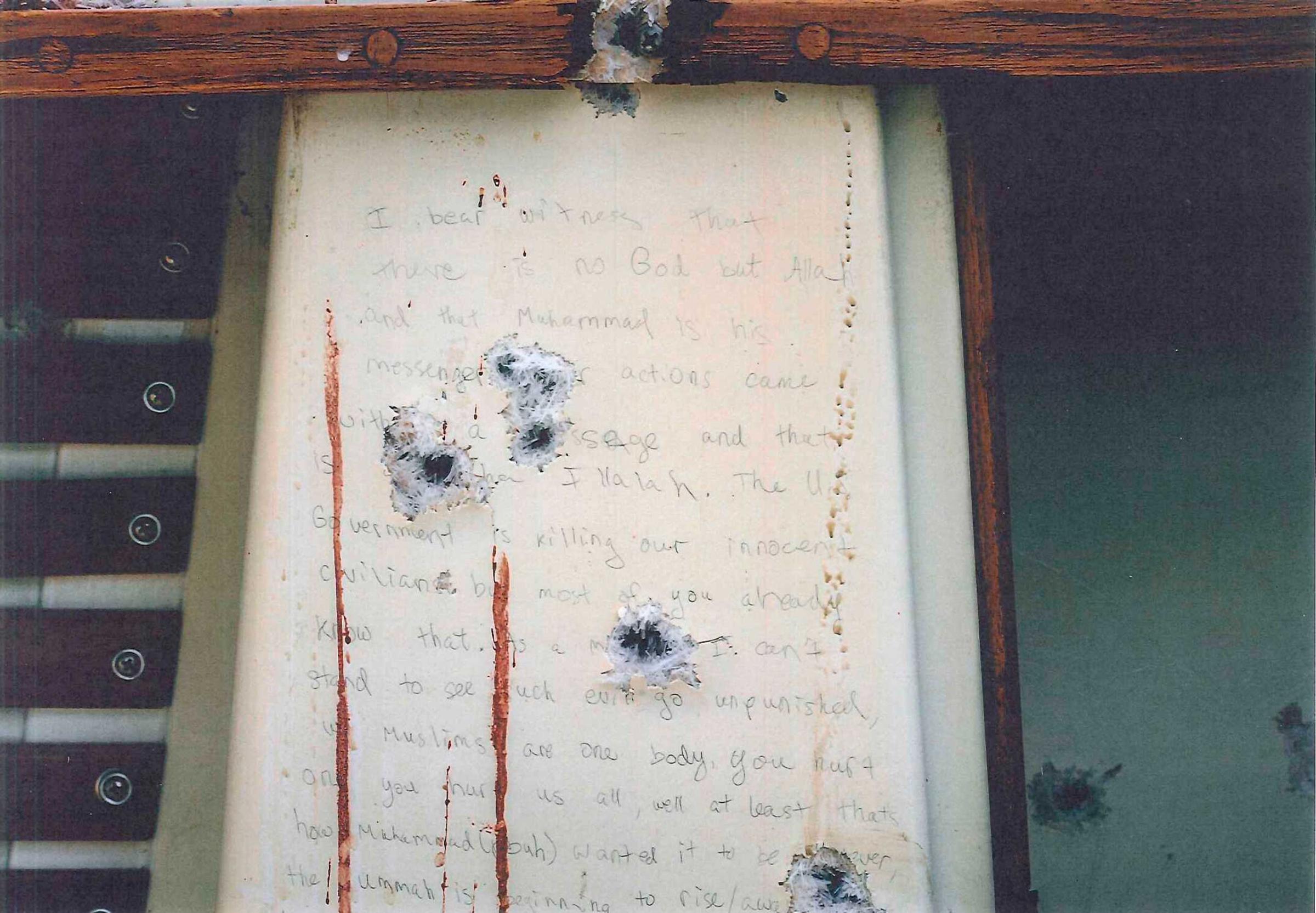

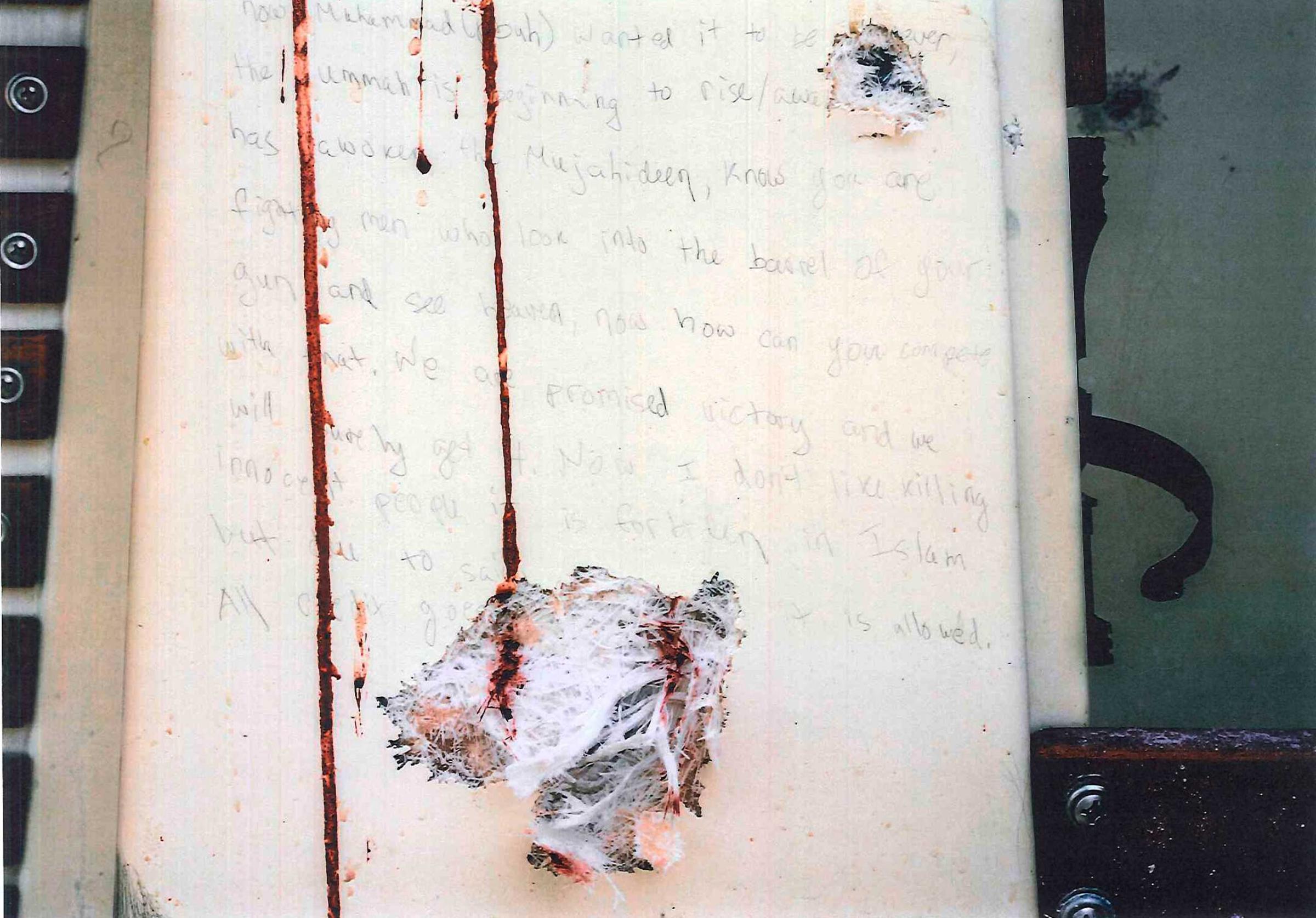

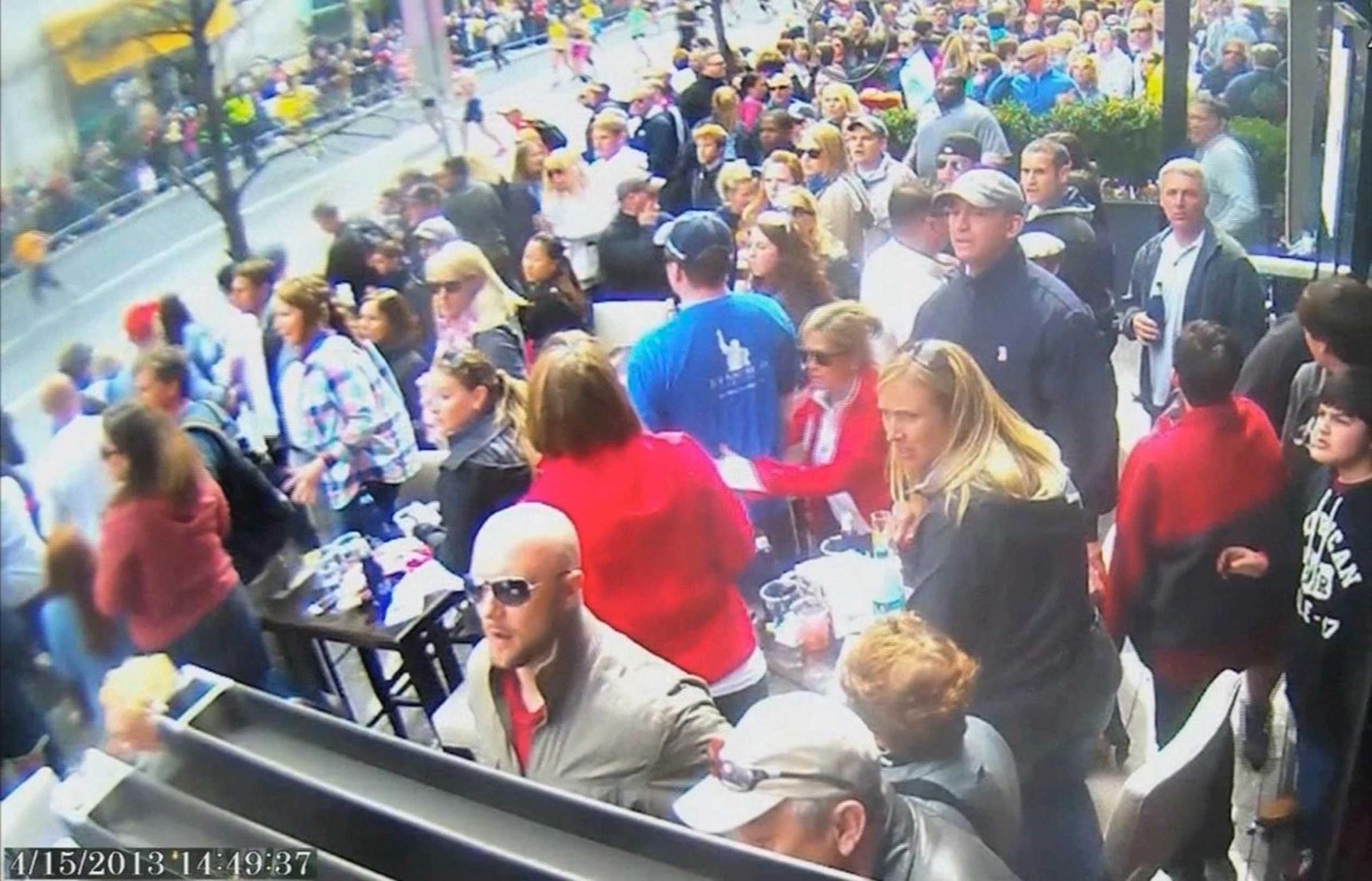

See Evidence From the Boston Bombing Trial

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Caitlin Clark Is TIME's 2024 Athlete of the Year

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com