Call them the dust busters: Scientists are now able to take a sample of dust, sequence the DNA of its fungi and microbes and figure out where it came from, according to new research published in the journal PLOS ONE. The application might prove useful in solving crimes.

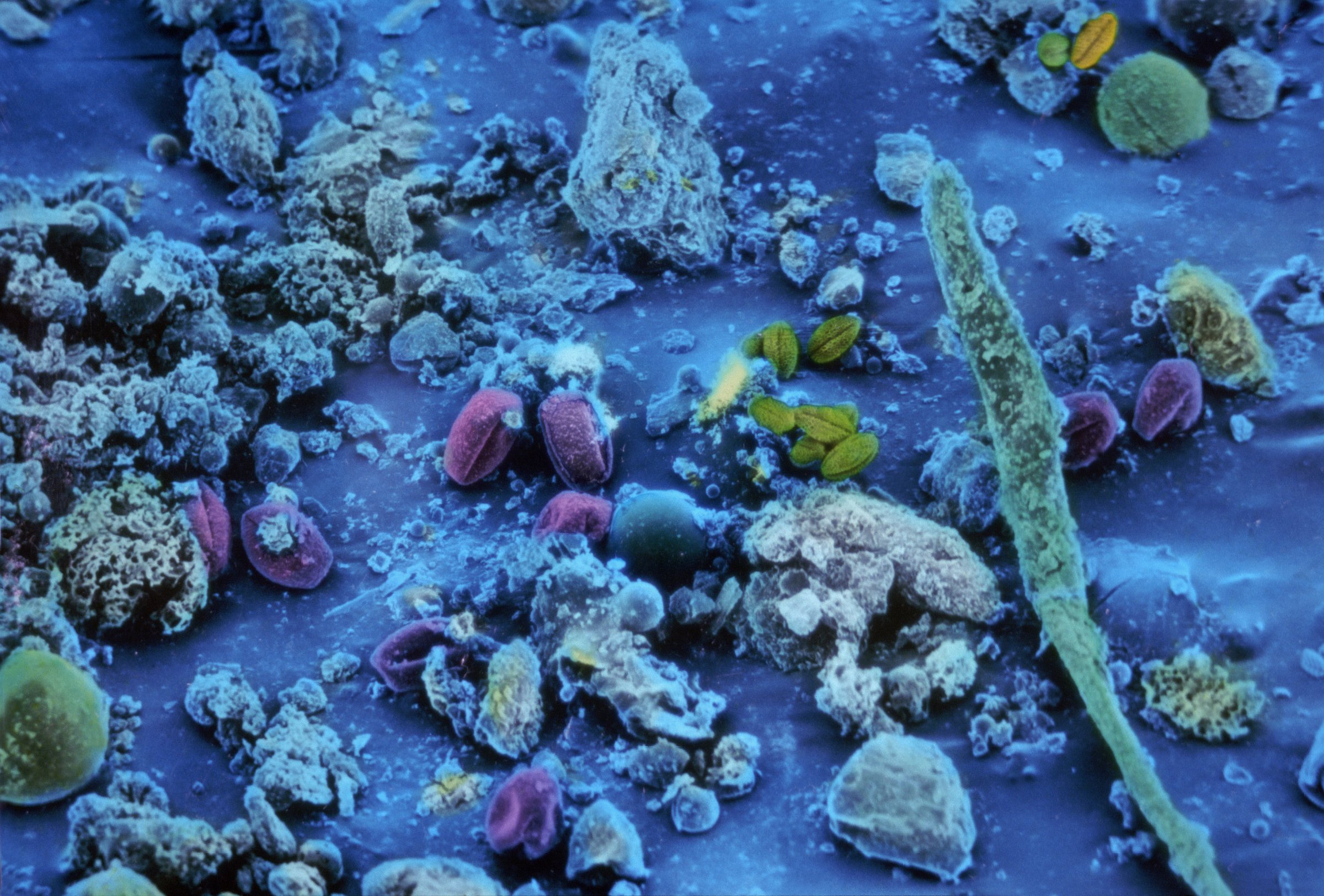

The researchers from North Carolina State University and the University of Colorado, Boulder, had about 1,000 people across the country swab their homes’ outer door frames and send in samples of the dust. A lab sequenced all that dust DNA—fungi, microbes and all—from every state but North Dakota. (The scientists have nothing against North Dakota. It’s just that no one from the state sent in a sample.) Our nation’s door frames are home to a mind-boggling amount of diversity; researchers identified 40,000 unique fungal taxa from the samples. A single home, by comparison, usually only harbors about 700 fungal taxa.

MORE: Your Tiny Roommates: Meet the Microbes Living In Your Home

Their goal was to glean where each fungal species tended to show up, which could be useful information in forensic investigations with this type of evidence. “We wanted to take either the presence or absence of these different species and get a smooth picture of where we expect the fungus to live,” explains Neal Grantham, one of the study’s authors and a PhD student in the department of statistics at North Carolina State University. By estimating the probability of seeing these different species at some location in the U.S., they were able to put a pin in a map of the most likely location of origin, he says. Half of their predictions got closer than 143 miles of the actual place of origin, and about five percent were within 35 miles of the dust’s doorframe.

Down the line, mapping out the microbes of dust could help with forensics and law enforcement investigations, Grantham says. “This is not the first study that shows you can use bacteria and fungi in a forensics setting. But what our work contributes is a more objective statistical way to tackle these problems,” he says.

The scientists are looking into whether the probability method might hold for other samples, like pollen. If it does, law enforcement could use a statistically sound probability instead of relying on pollen experts to divine where a sample might have originated, Grantham says.

“‘Humans are ecosystems’ is the big microbiome message,” Grantham says. Now, our doorframes might be ecosystems, too.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Write to Mandy Oaklander at mandy.oaklander@time.com