Here are the things Miika Thoeun Gove knows about her Cambodian origins: a woman claiming to be her grandmother said she couldn’t take care of her. An orphanage took her in. The U.S. embassy arranged for an airlift to California.

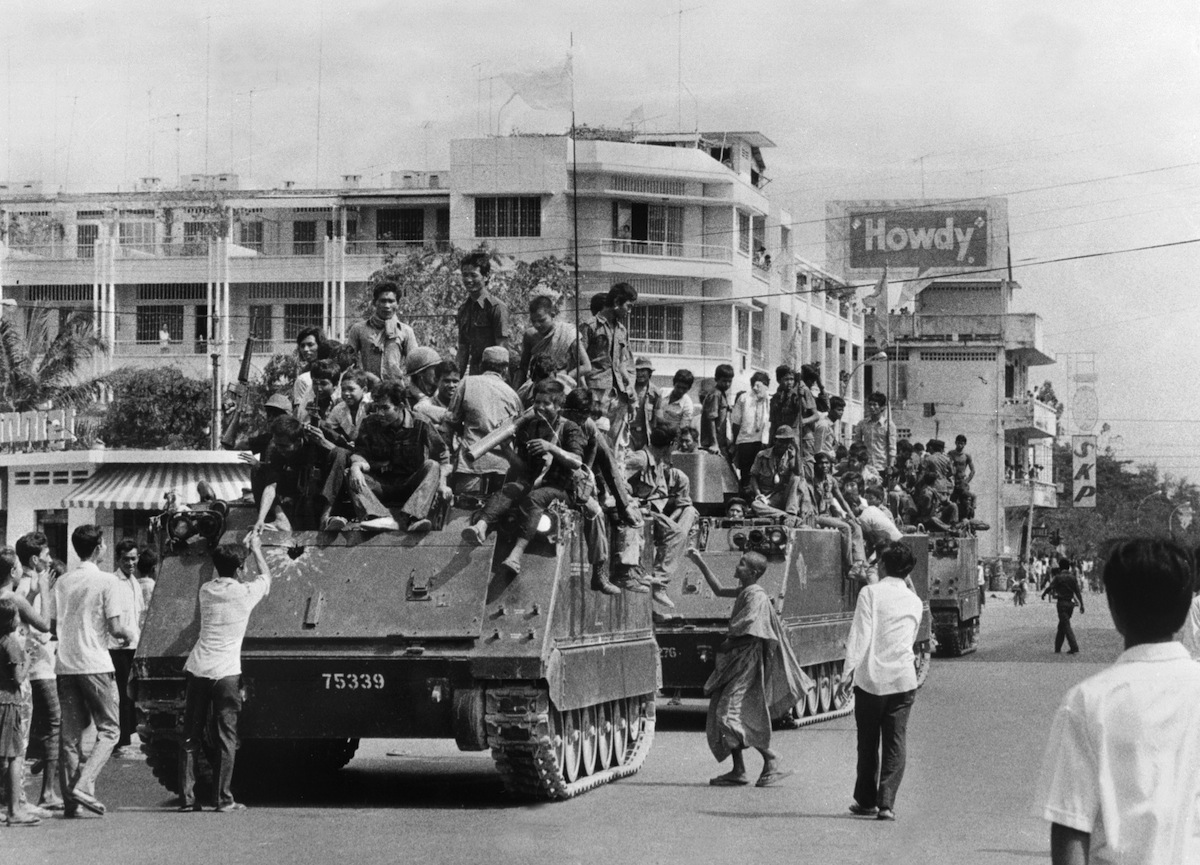

By the time the Khmer Rouge took control of Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975, Miika had been safely shuttled out, but her identity remained trapped inside. In Cambodia, Pol Pot’s brutal regime set about systematically dismantling all existing systems — killing an estimated 1.7 million people in pursuit of a harebrained “year zero” agrarian utopia. In the process families, institutions and records were obliterated amid one of the worst genocides of the 20th century. In the U.S., doctors estimated Miika’s age by looking at her teeth; new parents assigned a birth date, they gave her a name.

“I don’t know how it worked, there’s virtually no details other than [me] arriving,” she tells TIME. “I don’t even know if that’s the true story.”

Forty years ago this and last month, a series of planes flew into Phnom Penh’s besieged Pochentong airport on a special sortie. The Fighting Tigers at the controls dove down into the tarmac to avoid Khmer Rouge gunfire and — barely cutting the engines — pulled up alongside cargo trucks. With little ceremony, those in the truck began to load the plane with box after box of babies.

“As this telegram is being dispatched,” read a U.S. embassy cable sent just hours after a March 17 airlift, “the orphans are not the only ones heaving a king size sigh of relief.”

At the time of the evacuations, the U.S.-backed Khmer Republic had all but crumbled under the weight of incompetence and corruption, while large-scale American bombing of the countryside sent hundreds of thousands fleeing to Phnom Penh for safety. Desperate parents — starving and fearing for their lives — overwhelmed the state-run orphanage; the babies would not stop coming.

Canadian sisters Eloise and Anna Charet arrived in the country just months before the fall to open a private orphanage, called Canada House. Eloise recalled taking babies and toddlers from a room in the state orphanage, “where the children were just left on mats and were left to die. The ants were crawling on them, the flies all around their eyes and mouth … the only thing you could see was the flickering of their eyes once in a while and this room was just packed with children left to die, they didn’t know what to do.”

On March 17, the sisters successfully evacuated all 43 of their charges — an unlikely feat that allowed for scores more to be pulled out in the following weeks by various private agencies and individuals. Most of the Cambodian children were initially sent to war-torn Saigon where they were thrown in with more than 3,000 Vietnamese children to be airlifted out to the U.S., Europe and Australia in the audacious and controversial “Operation Babylift.”

As the situation in Cambodia deteriorated, its envoys in Washington, D.C., begged the U.S. for assistance and arranged for a final group of 220 orphans to be pulled out and adopted. In Phnom Penh, the Minister for Refugees scrambled to process the children. On April 9, 28 flew out. They were to be the last.

“I messaged [Refugee Minister] Kong Orn … about the orphans’ situation. I also messaged other officials. But there was no answer from anyone. Clearly the subject of orphans was not on anyone’s mind at the time,” says Gaffar Peang-Meth, a diplomat based at the Cambodian embassy.

The chaos surrounding those final flights ensured that many orphans arrived with only the scantest of documentation. In a July 1975 internal report, the U.S. Agency for International Development recorded that half of the 108 orphans airlifted out of Phnom Penh “are experiencing legal problems regarding their adoptability and/or placements.”

“The placement of the orphans … in adoptive homes has been held up because of questions raised regarding their adoptability and/or prospective placement. Due to the emergency situation which existed at the time, the sponsoring agencies and the government did not obtain the proper releases or process other required documentation,” the report continued.

In California and elsewhere, lawsuits proliferated over whether the children were in fact orphans. Miika and scores of other children spent upwards of a year in foster homes while officials debated their status. Four decades later, some have yet to be naturalized.

“The children’s arrival was not all smooth and happy,” recalls Gaffar Peang-Meth, who became the point man for verifying many of their legal status. Some news media reports suggested that the children were not all orphans and openly questioned why they had been brought to the U.S. Gaffar Peang-Meth responded that there was no authority in Phnom Penh to answer such allegations.

Amid the mounting concern, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) ordered a temporary halt to the babylifts on April 16, just one day before the Khmer Rouge seized Phnom Penh. Then deputy commissioner of the INS, James Green, told the Washington Post that the agency would “launch a full investigation to determine what these children’s backgrounds are and how they got into the United States.”

By then, of course, the lines of communication had already been severed. With it went any hope of tracking down family ties.

Adoptees grew up oblivious to their roots, yet haunted by them.

“No matter how you grow up childhood always challenging, but not really having a mental foundation of how it started, that’s really challenging,” says Miika Thoeun Gove. “I can’t even reach out to anyone in the group that I flew out with, I have no information.”

A handful of the orphans have returned to Cambodia in search of more information, though such quests tend to be fruitless.

Kim Routhier-Filion, one of the Canada House babies, traveled to Cambodia in 2012 accompanied by Eloise and Anna Charet, and a film crew from the French-Canadian news station RDI. While there, the filmmakers captured Routhier-Filion looking through records and speaking with archivists, but he confessed scant faith in reconciliation.

“For me, my adoptive parents are my real parents,” he said. “I didn’t have any expectations of finding my biological parents in Cambodia. I assume they got killed. I don’t even know my biological mom’s name. I didn’t have any hope or expectations of that.”

Gove, whose documents carry neither the name of her parents nor birthplace, has similarly little anticipation of closure. It is something, however, she has come to accept.

“Imagine the children who didn’t get out of there,” she points out calmly. “I figure I’m doing O.K.”

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com