If you’re a child of the 1990s, R.L. Stine has probably kept you up at night with his books. But while he’s best known for Goosebumps, he’s back to freaking out teenagers with Fear Street, the young-adult horror series that has sold more than 80 million copies since 1989.

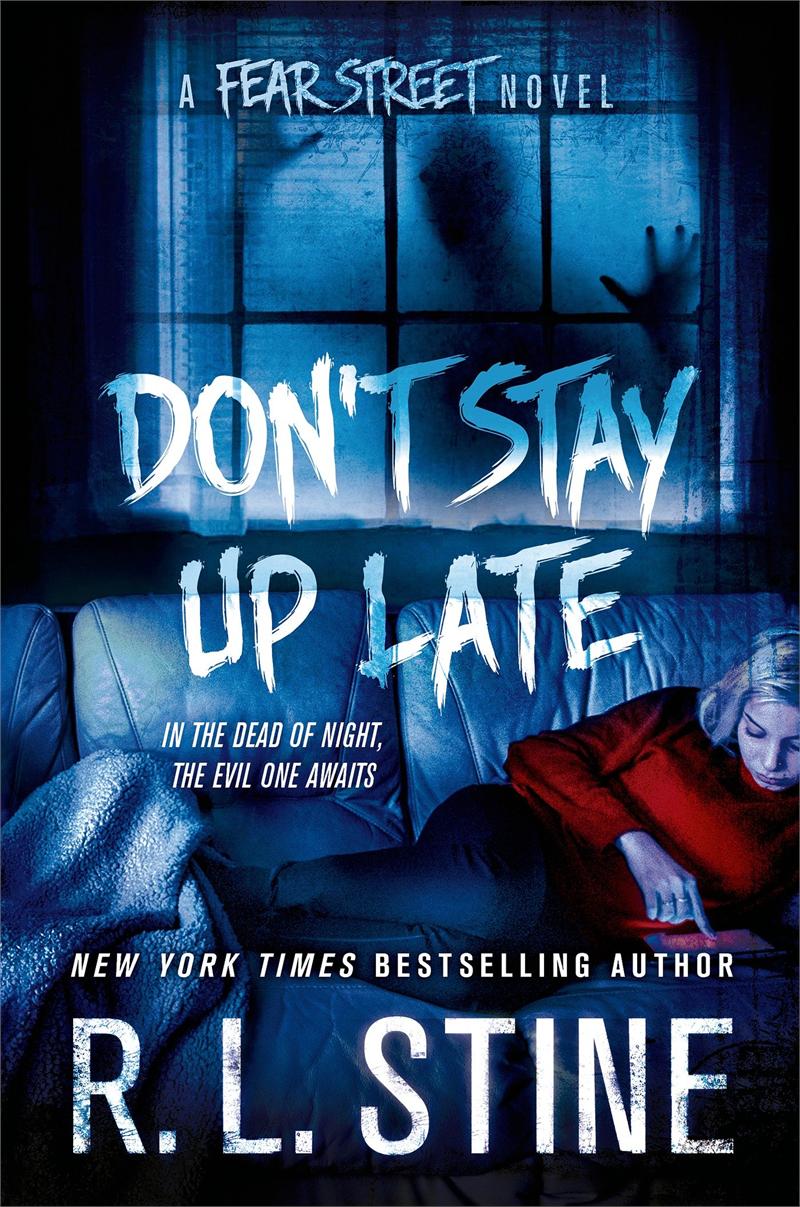

After reviving the books in 2014, Stine returned to the city of Shadyside this month with Don’t Stay Up Late, about a girl named Lisa whose odd new babysitting job holds the key to a recent string of murders and the horrible nightmares that plague her. TIME spoke to Stine about his writing process, connecting with old fans on Twitter and what it takes to scare teenagers today.

TIME: April seems like a strange time to put out another horror book. I would have assumed your whole life revolves around the month of October.

R.L. Stine: That’s not a career—you can’t just do Halloween! [Laughs] That’d have to be year-round.

You said Don’t Stay Up Late was possibly your scariest one yet. What makes it so?

I think that was Twitter hype.

You’ve killed off a lot of teenagers in Fear Street. I’d imagine today’s generation of teenagers would be the most fun to write about yet.

It’s actually much harder, because the technology has ruined a lot of things that make for good mysteries—largely because of cell phones. You can’t have a mystery caller anymore. You can’t have someone making horrible phone calls and you don’t know who it is. Now, you know immediately. You look at your phone, and you know. You have to get rid of the phone when you’re writing the book. Everyone has a phone now and everyone can just call for help. In some ways, it’s much more challenging now.

How concerned are with you with capturing contemporary teen life?

I have to keep up with them. It’s a real important part of writing these books. You don’t want to sound out of date at all, but I’m very careful because the technology changes every two weeks. You have to be not terribly specific about what they’re using. And I have to be careful about language too. I spent a lot of time going to schools and talking to teenagers and kids for Goosebumps, just to see what they say, how they talk these days, what they wear, that kind of thing. But if I put too much of that in the book, it dates it.

So no Snapchat killer or One Direction zombie murderers?

[Laughs] No, I probably, I wouldn’t do that. Because in a month, that would be [over], and then you look like you don’t know what you’re doing. The lucky thing about horror is that the things that people are afraid of, it never changes. Afraid of the dark, afraid someone’s in the house, afraid someone’s under your bed—that’s the same.

How much do you care about making the dialogue sound realistic?

My rule for writing teenage dialogue is no complete sentences. You know someone doesn’t know teenagers when the teenagers are speaking in complete sentences, because they basically don’t. I remember when my son was a teenager—he basically grunted. [Laughs]

What’s off-limits in these stories? I know you don’t put larger social messages in there.

No messages, except that the ordinary teenagers faced with horrible things can use their own wits and imagination to survive, to triumph. That’s the only message that I ever put in. There’s a lot of real-world stuff that I don’t put in Goosebumps or Fear Street. In Goosebumps, no one ever dies. In Fear Street, you want to make sure that it’s a fantasy that’s not too real. There are no drugs in Fear Street. There’s no child abuse. There are hardly even divorced parents. Other teen horror writers have done a lot with teens with drugs and that kind of thing, but I don’t do it. My basic rule is they have to know it’s not real. That it’s fantasy.

You received a lot of negative feedback from readers when you featured an unhappy ending in Fear Street, which surprised me — it seems like in the most popular YA stories today, the grey areas and moral ambiguity are a big part of the appeal.

Not in these horror novels. They want happy endings in these. I learned my lesson that time. The kids really turned against me. It was immediate. I got these letters. “Dear R.L. Stine, you moron. You idiot. How could you do that? When are you going to finish the story?” They just couldn’t accept it. I would do school visits, and that book haunted me. The hand would go up: “Why would you write that book? Why did you do that?” Maybe it’s changed, but I’m not going to try it!

What do you hear from people who read your books as kids and then revisit them as adults?

That’s why I’m on Twitter. It’s such a great way to keep in touch with the ‘90s kids, with my original readers. And I have to say, it was very good for my ego because all day long I hear, “I wouldn’t be a librarian today if it wasn’t for you!” Or “I wouldn’t be a writer today if it wasn’t for you!” Or “Thank you for getting me through a really tough childhood.” It’s very gratifying. It’s almost too nice.

Do people pitch you ideas on Twitter?

There’s not really enough room for them to write. It is interesting, people ask if they can collaborate on a book. One woman wrote to me on Facebook—this was great—and she said, “I have an idea for a horror novel called The Ghost Ship, but I don’t know what the plot would be. Do you think you could write it for me?’

That sounds like the start of its own horror novel.

[Laughs] That’s good, right? This morning on Twitter, a young woman said, “I’m sure you’ve written a book called April Ghoul’s Day, I’m going to go find it.” And I said, “What a great title!” I’m gonna have to steal it from her, I think! I never thought of it.

What is your writing routine like these days?

It’s sort of factory work, you know. I still enjoy it so much, so I just keep going. I still do a lot of books every year. I start around 9:30 in the morning and I write 2,000 words a day. I just go by words. And then I’m totally brain-dead and go out, take the dog for a walk and that’s it. I work maybe five, six days a week. If I started at, say, 10 in the morning, I’m done by 2:30. Those are good hours, right? You can’t complain about those hours!

Do you write on a computer?

Yeah, but I cannot outline on a computer. I do a chapter-by-chapter outline of every book. I can’t work without an outline. I have to know everything that’s going to happen in the book first. It’s one of these mysterious things. I have to write it by hand, and it comes so much better. But I would never write [the book] by hand.

There’s something about getting it out on paper first that I find very helpful in the brainstorming stage

I don’t even print manuscripts anymore at all. I had these universities asking for my archive–I have no archive! [Laughs] They say, “We would love to house your archives.” Well, one thing when you live in an apartment is you can’t keep things, right? I can’t keep stacks of old manuscripts and letters. I have no archive at all. I have nothing. It’s kind of embarrassing.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Nolan Feeney at nolan.feeney@time.com