Correction appended, April 14

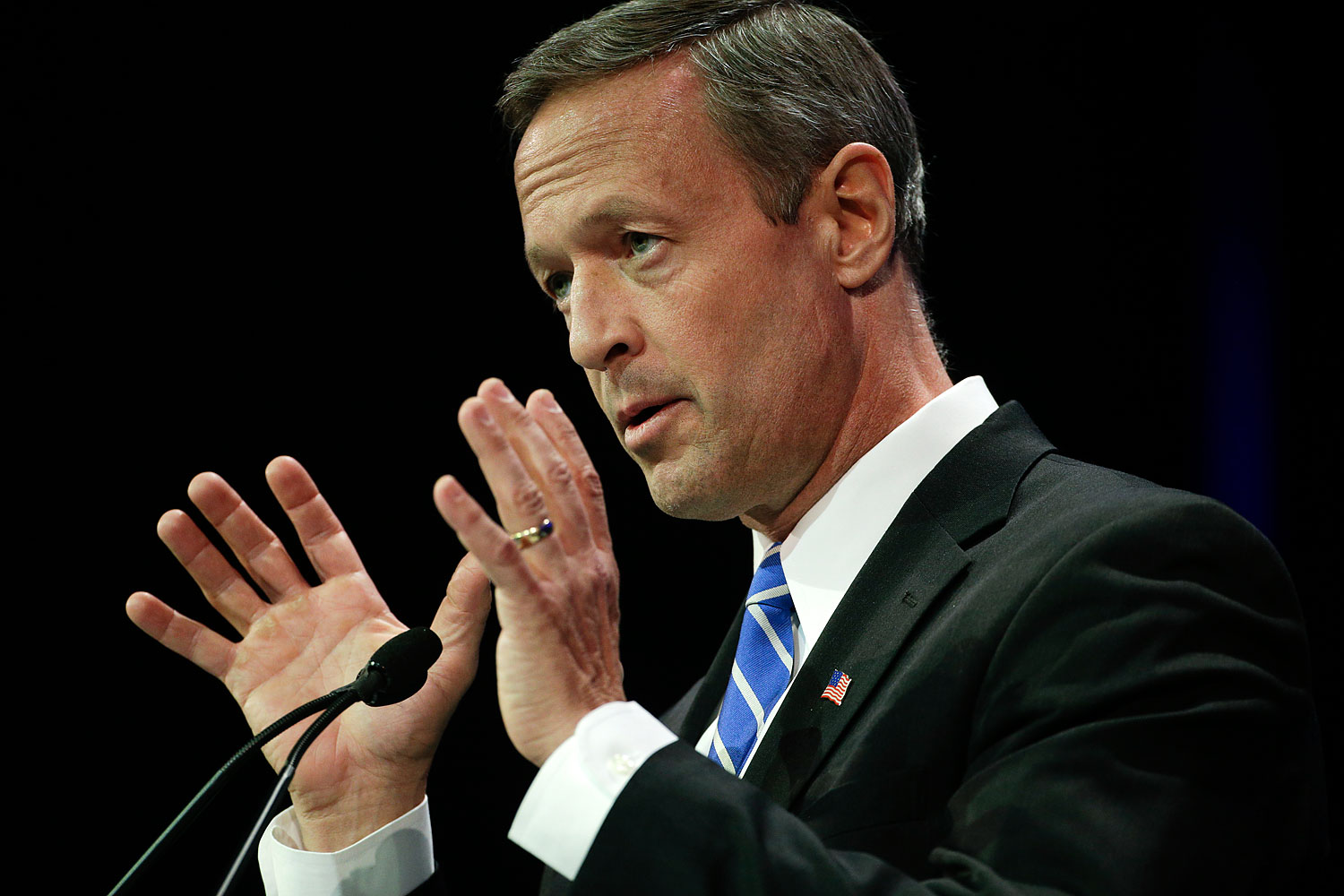

On a breezy Saturday night in March at a small Tex-Mex restaurant in rural western Iowa, Martin O’Malley climbed onto a chair. The former governor of Maryland, who was in the American heartland prepping his likely presidential campaign, looked over the 80-person crowd from his rickety purview. “This is not my first visit to Iowa,” he told the gathered Democrats. “I know this very personally: How each of you, as Iowans, take your participation in the Iowa caucus.”

Iowans insist on meeting candidates— “three times,” O’Malley continued to laughs. “Being able to look them in the eyes, being able to ask them questions.” Then O’Malley walked up to the guitarist in the three-piece band in the corner, grabbed his axe, and taught the audience the chorus to Passenger’s “Scare Away the Dark.” He worked the crowd afterward, circling the room and shaking as many hands as he could. “He was one of the last ones to leave,” says Linda Nelson, the Pottawatomie County Democratic chair. “It was a good old hoe down.”

O’Malley has another song up his sleeve: he’s bringing heart to the crucial Iowa caucus. An all-but-declared candidate, O’Malley is preparing for a committed campaign in Iowa, recruiting staff, courting local activists, and touring the Hawkeye state’s cities and backwater towns. His roots in the state go back to 1983, when he spent months campaigning for presidential candidate Gary Hart. Now, he is massaging Iowa voters as the 2016 campaign gets underway, courting local progressives and firing up the base.

As Hillary Clinton prepares to officially launch her presidential campaign on Sunday, many Iowans are already frustrated with the former secretary of state. She’s been too slow to announce her candidacy, they say, and she hasn’t visited the state since October. Iowa liberals say she appears emotionally uninvolved, as she did in 2007, when her loss to Senator Barack Obama set her on the road to defeat. Iowa Democrats expect a robust primary campaign in their state. Nature abhors a vacuum, and O’Malley has swooped in.

O’Malley can be a wooden public speaker. A policy wonk former Baltimore mayor and Maryland governor, he relies more on statistics than oratorical flair. He’ll speak in paragraphs to voters and reporters before finding a pithy line. At home, his two-term legacy in Annapolis is at risk of being undone after his chosen successor lost to a Republican in the latest gubernatorial contest. He may have met plenty of Iowa farmers, suits and homebodies campaigning for Hart in 1983, but as of February, 84% of Iowans didn’t know enough about the former governor to judge him, according to a Quinnipiac poll—and that’s a year and a half after he said he was preparing a presidential run. In the coming presidential contest, Hillary Clinton has the advantage of near-universal name recognition as well as a large campaign staff.

But in a state with a highly contentious caucus and a studied ambivalence toward Clinton, a progressive troubadour like O’Malley is quickly attracting Iowa Democrats. “Hillary Clinton is not inevitable,” says George Appleby, a prominent Des Moines lawyer who has been involved in numerous Democratic campaigns in Iowa and now supports O’Malley. “There’s a history of Iowa caucuses catapulting a second person to take on the inevitable.”

Iowa has long propelled minor Democratic candidates closer to a nomination, including one that O’Malley worked for three decades ago. He first set out for Iowa as a 20-year-old campaign worker for then-Senator Gary Hart, toting a guitar and a penny whistle as he crisscrossed the counties, knocking on doors and making phone calls. O’Malley spent many weeks sleeping in living rooms and driving around in the campaign’s “Van Force 1,” scouring up votes for the Democratic upstart who nearly went on to take the nomination in 1984. Hart made a strong impression on O’Malley—the 21-year-old had his first legal beer with the Democratic candidate in 1984—and apparently the feeling was mutual. “We heard that they just loved him out there,” Hart told the Baltimore Sun in 1999. “Particularly the housewives.”

As part of O’Malley’s reunion tour with Iowa, he’s visited the state twice in the last three weeks, driving in March from a county fundraiser in Davenport in the blue, eastern part of the state to Council Bluffs out in the rural west of Iowa. This week, he will appear at three Democratic events around Des Moines. Signs point toward O’Malley working a hard operation in Iowa.

MORE: How Liberals Hope to Nudge Hillary Clinton to the Left

“Iowa is a grinder-type operation. You have to go through a lot of counties, meet a lot of people, shake a lot of hands,” says Bill Hyers, a senior adviser to O’Malley. “He loves that. He did it with Gary Hart. He loved it then and is still very nostalgic about it.”

O’Malley “has an understanding of what it takes to do this,” Hyers said. “He has been talking to these folks for years, but now he can talk in a serious way about how he can move the country forward.”

As Baltimore mayor, O’Malley implemented data-intensive metrics to track crime and quotidian municipal workings like pothole fixes and snow removal. Crime fell in the murder capital of the United States by 24% during the first five years of his mayorship, and the mayor’s office said the city had saved hundreds of millions of dollars through O’Malley’s data-tracking program. Though Maryland benefits economically from its proximity to Washington, D.C., the state went from fifth highest per capita income to first during his tenure as governor. Laws he signed toughening up gun control measures, ending the death penalty and putting gay marriage up for a successful referendum will endear him to progressives, even if they cost him some support among other voters.

In his recent Iowa events, O’Malley has pointed to his governing record. He’s advocated reinstating the Glass-Steagall Act, a rule that separated commercial and investment banking in the United States until President Bill Clinton dissolved it. He talks about raising the minimum wage, reining in Wall Street and pushing immigration reform. O’Malley is presenting himself as the deep-blue Democrat that can proudly carry a progressive message, and so far, Iowans are buying it.

“Martin O’Malley is a very progressive potential candidate,” says Larry Hodgden, chair of the Cedar County Democrats. “I think he can carry the progressive message. And we’ve got to have somebody whose going to fight for the people.”

Though Clinton polls leagues ahead of O’Malley and has a deep network of wealthy donors eager for her to run, Iowa will be a particular challenge for her campaign. In 2007, she struck voters as indifferent, and didn’t effectively engage in the kind of living room-and-diner politics that the first-in-the-nation voters expect. She placed third in the state behind then-Sen. Barack Obama and the more progressive Sen. John Edwards.

Clinton aides have said 2015 will be different. She plans to visit Iowa this week after her Sunday campaign launch, and advisors have said Clinton will stick to small events and treat the state seriously. If Clinton campaigns earnestly in Iowa this year as expected, she will no doubt outperform her 2008 disaster. But even so, there is room for O’Malley to shine if he can consolidate the progressive base that has never warmed to Clinton.

“The beauty of Iowa is that you could be absolutely a no one with no money, and you don’t need it. If you’re in small settings and you have a message, people will listen to it,” says Democratic strategist Joe Trippi. “O’Malley is focused on the right place.”

MORE: Iowa Activists Are More Than ‘Ready for Hillary’

Last year, O’Malley spent time campaigning and fundraising for Democrats in Iowa City, Des Moines and Cedar Rapids, as well as many of the smaller towns like Sioux City, Ottumwa and Beaverdale. He visited diners, a Baptist church, and other Democratic watering holes. The Iowa beneficiaries of his 2014 tour can be turned into O’Malley benefactors in 2015, when he begins campaigning for his probable bid.

O’Malley will likely campaign in Iowa at Clinton’s ideological left and aim to attract the committed progressives in the state who once supported Obama and former North Carolina Sen. John Edwards. Iowa has a devoted cadre of Sen. Elizabeth Warren enthusiasts who are looking for a liberal candidate. Volunteers for the Run Warren Run PAC are ramping up social media efforts. With Warren insistent she will not enter the race, they represent a coveted cadre voters who will flock toward a progressive.

“If you have a two-person contest for an open seat, the person who isn’t as well known has a number of advantages,” says Anita Dunn, a Democratic strategist who worked for Obama. “That candidate can be a repository of anyone who doesn’t want to immediately step behind the frontrunner.”

O’Malley has promised a final decision by the end of the spring. He runs the risk of waiting too late to enter the race: going from near-anonymity in Iowa to populist upstart in a few months is a steep hill to climb. But if there’s any place for O’Malley to launch toward the national stage, it’s in the Hawkeye State.

“The fact that O’Malley starts out with low name recognition doesn’t mean that anyone should underestimate him,” says Dunn. “The reason Iowa and New Hampshire go first is for candidates like O’Malley.”

In a packed Irish pub in Des Moines on Thursday night, O’Malley entertained the audience with another rendition of “Scare Away the Dark.” The song’s lyrics hinted at the coming campaign. “Feel, feel like you still have a choice,” he sang. “If we all light up we can scare away the dark.”

The next day, O’Malley was off to a local Democrats’ dinner. Speaking to reporters, O’Malley recounted lessons learned from the 1984 race, when Gary Hart came from behind in Iowa and walked onto the national stage. “History is full of examples where the inevitable front-runner was inevitable right up until she was—or he was—no longer inevitable,” he said. “And the challenger emerges very often right here in Iowa.”

— Additional reporting by Zeke Miller / Des Moines, Iowa.

Read next: Martin O’Malley Courts Elizabeth Warren Supporters in New Hampshire

Correction: The original version of this story incorrectly described Beaverdale. It is a neighborhood in Des Moines, Iowa.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com