Evil isn’t easy. Say what you will about history’s monsters, they had to overcome a lot of powerful neural wiring to commit the crimes they did. The human brain is coded for compassion, for guilt, for a kind of empathic pain that causes the person inflicting harm to feel a degree of suffering that is in many ways as intense as what the victim is experiencing. Somehow, that all gets decoupled—and a new study published in the journal Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience brings science a step closer to understanding exactly what goes on in the brain of a killer.

While psychopaths don’t sit still for science and ordinary people can’t be made to think so savagely, nearly anyone can imagine what it would be like to commit the kind of legal homicide that occurs in war. To study how the brain reacts when it confronts such murder made moral, psychologist Pascal Molenberghs of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, recruited 48 subjects and asked them to submit to functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), which could scan their brains while they watched three different scenarios on video loops.

In one, a soldier would be killing an enemy soldier; in the next, the soldier would be killing a civilian; and in the last, used as a control, the soldier would shoot a weapon but hit no one. In all cases, the subjects saw the scene from the shooter’s point of view. At the end of each loop, they were asked “Who did you shoot?” and were required to press one of three buttons on a keypad indicating soldier, civilian or no one—a way of making certain they knew what they’d done. After the scans, they were also asked to rate on a 1 to 7 scale how guilty they felt in each scenario.

Even before the study, Molenberghs knew that when he read the scans he would focus first on the activity in the orbitofrontal cortex, a region of the forebrain that has long been known to be involved with moral sensitivity, moral judgments and making choices about how to behave. The nearby temporoparietal junction (TPJ) also takes on some of this moral load, processing the sense of agency—the act of doing something deliberately and therefore owning the responsibility for it. That doesn’t always makes much of a difference in the real world—whether you shoot someone on purpose or the gun goes off accidentally, the victim is still dead. But it makes an enormous difference in how you later reckon with what you’ve done.

In Molenbergh’s study, there was consistently greater activity in the lateral portion of the OFC when subjects imagined shooting civilians than when they shot soldiers. There was also more coupling between the OFC and the TPJ—with the OFC effectively saying I feel guilty and the TPJ effectively answering You should. Significantly, the degree of OFC activation also correlated well with how bad the subjects reported they felt on their 1 to 7 scale, with greater activity in the brains of people who reported feeling greater guilt.

The OFC and TPJ weren’t alone in this moral processing. Another region, known as the fusiform gyrus, was more active when subjects imagined themselves killing civilians—a telling finding since that portion of the brain is involved in analyzing faces, suggesting that the subjects were studying the expressions of their imaginary victims and, in so doing, humanizing them. When subjects were killing soldiers, there was greater activity in a region called the lingual gyrus, which is involved in the much more dispassionate business of spatial reasoning—just the kind of thing you need when you’re going about the colder business of killing someone you feel justified killing.

Soldiers and psychopaths are, of course, two different emotional species. But among people who kill legally and those who kill criminally or promiscuously, the same brain regions are surely involved, even if they operate in different ways. In all of us it’s clear that murder’s neural roots and moral roots are deeply entangled. Learning to untangle them a bit could one day help psychologists and criminologists predict who will kill—and stop them before they do.

Read next: What Binge Drinking During Adolescence Does to the Brain

The Wolf of Wall Street

This saga of white-collar crime is slightly less violent than other true-crime films, but no less debauched. Based on Jordan Belfort’s memoir of the same title, we follow the stockbroker along his meteoric rise as he cons his way to making millions of dollars through illegal trades, eventually culminating in an unraveling personal life and criminal charges. A surprising number of the movie’s hijinks are factual, according to the memoir.

Monster

The biopic follows Aileen Wuornos (played by Charlize Theron), a prostitute who kills a series of johns, claiming each one was trying to rape her. She confesses when it seems like her lover, Tyria Moore (Christina Ricci) might be implicated in the crimes. Wuornos was executed in 2002.

American Gangster

The Denzel Washington vehicle depicts Frank Lucas as a criminal mastermind, running a massive Harlem crime ring funded by his drug business. In real life, Lucas did indeed make a major profit on heroin imported from Southeast Asia, cutting out the middlemen, but he denies ever having stashed it inside the caskets of American casualties being shipped home from the Vietnam War. The movie makes Lucas out to be a major informer on crooked cops and fellow drug dealers when he’s caught; the real Lucas has denied this.

Goodfellas

The Scorcese classic leaves out a few moments from Henry Hill’s life, but the New York gangster (played by Ray Liotta) really was in the Lucchese crime family. As in the movie, he was part of the Air France robbery and the cover-up of the murder of Billy Batts. He did indeed enroll in the Witness Protection Program with his family, but was kicked out after a few years for committing crimes. He died in 2012.

The Black Dahlia

The movie takes as its starting point the still-unsolved 1947 murder of Elizabeth Short, whose naked corpse was discovered cut in half in a lot in L.A. But from there, it departs from the facts greatly, diverging into sordid, murderous plots affecting the police officers investigating the case and the women in their lives.

The Bling Ring

A group of teens and young adults get their kicks robbing celebrities, breaking into their homes and taking their pick of jewelry, clothing, cash and more. The criminals’ names were changed for the Sofia Coppola film, but several of the real rich victims appear—Paris Hilton, for instance, even agreed to let scenes be filmed in her home.

Zodiac

The Zodiac Killer case remains unsolved, but this David Fincher movie focuses more on the investigators than the criminal. Police detectives and reporters try to unscramble clues from a killer who sends ciphers with hints about his murders in northern California in the late 1960s and early 70s. The case consumes one journalist (Robert Graysmith, the author of the book the film is based on) to the point that he loses his job and his wife.

Foxcatcher

The Steve Carell, Channing Tatum and Mark Ruffalo movie dramatizes the relationship between John du Pont and two wrestlers who trained and lived on his facilities at Foxcatcher. He eventually shoots one of the brothers dead. In real life, du Pont was indeed convicted of the murder, but the details of his relationship with the Schultz brothers differ: for instance, the two never lived on the estate at the same time.

American Hustle

The names and some details may be different, but general arc of the David O. Russell con movie is fairly true to the events of the Abscam operation. The FBI really did use a swindler (Mel Weinberg in real life) to bust politicians taking bribes, and they really did pose a man as a fake Arab sheikh to catch them in the act of accepting his money.

Bully

A group of teenagers plots vengeance on a friend and bully who has raped two of them. They bring their target, Bobby, to a swamp where several members of the group participate in his violent killing. In real life, all seven of Bobby Kent’s killers were prosecuted and received varying sentences.

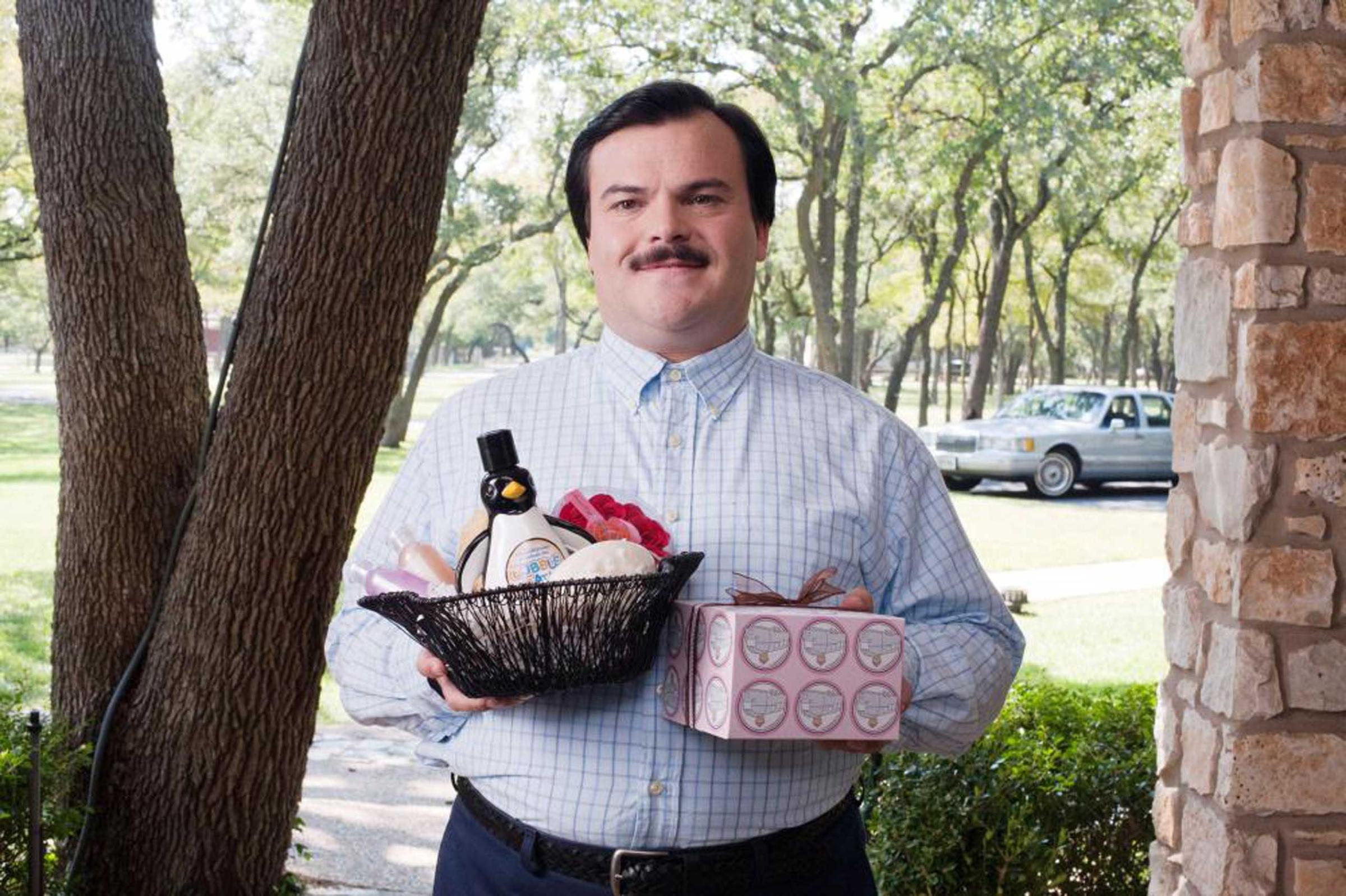

Bernie

Jack Black plays Bernie Tiede, a charming, do-gooder funeral director in Carthage, Texas, who befriends a much-older millionaire widow, Marjorie Nugent. Their relationship grows strained, and he shoots her and hides her body in the freezer. The film sticks fairly close to the facts—including the townspeople’s continuing support for Bernie even after he confessed. After the movie came out, the real-life Tiede was released after 17 years in prison based on evidence that he’d been abused as a child and his outburst was tied to Nugent’s controlling relationship with him. The court ordered Tiede to reside in the garage apartment of the filmmaker, Richard Linklater, on his release.

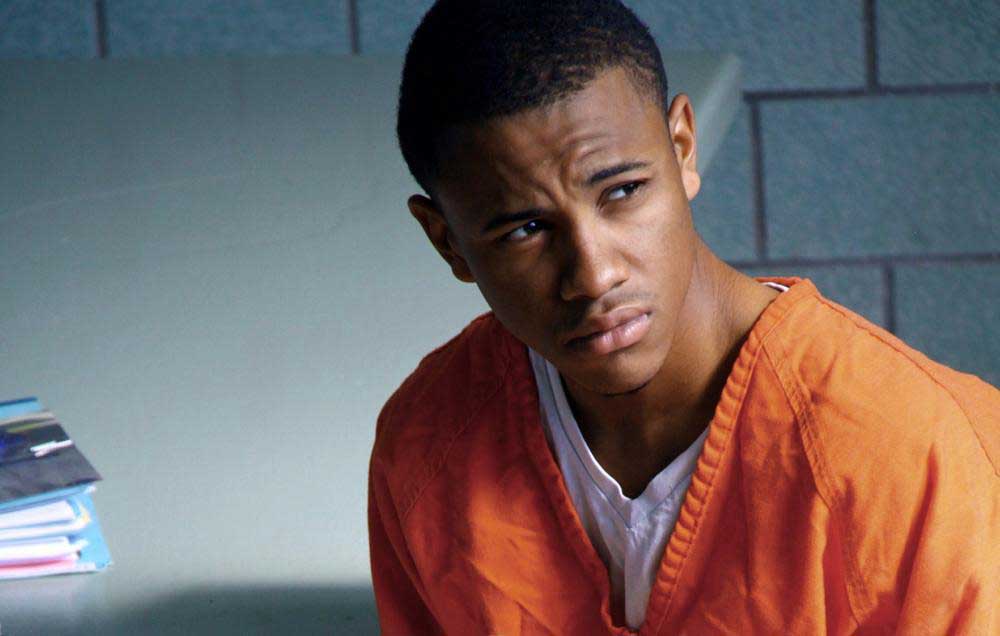

Alpha Dog

The names were changed for this Nick Cassavetes movie, but the story follows the same arc: Johnny Truelove (whose real-life name is just as ridiculous: Jesse James Hollywood) is an L.A. drug dealer who exerts major influence on his debtors. When Jake Mazursky (in real life, Benjamin Markowitz) can’t pay back the money he owes, Truelove and his associates kidnap Jake’s half brother, Zack (really Nicholas). He enjoys his time in captivity, however, and makes no effort to escape. But fearing that they can’t set him free without going to jail, several of Truelove’s cronies take Zack into the woods where he’s shot and buried in a shallow grave.

Blue Caprice

The film documents the relationship between teenager Lee Boyd Malvo and his farther figure, John Allen Muhammad, who terrorized the Washington, D.C. area in a weeks-long shooting spree that killed 10 and wounded others in the Beltway sniper attacks of 2002. They trained their rifle on random civilians through the back window of a blue Chevrolet Caprice. Malvo is serving several consecutive life sentences; Muhammad was executed in 2009.

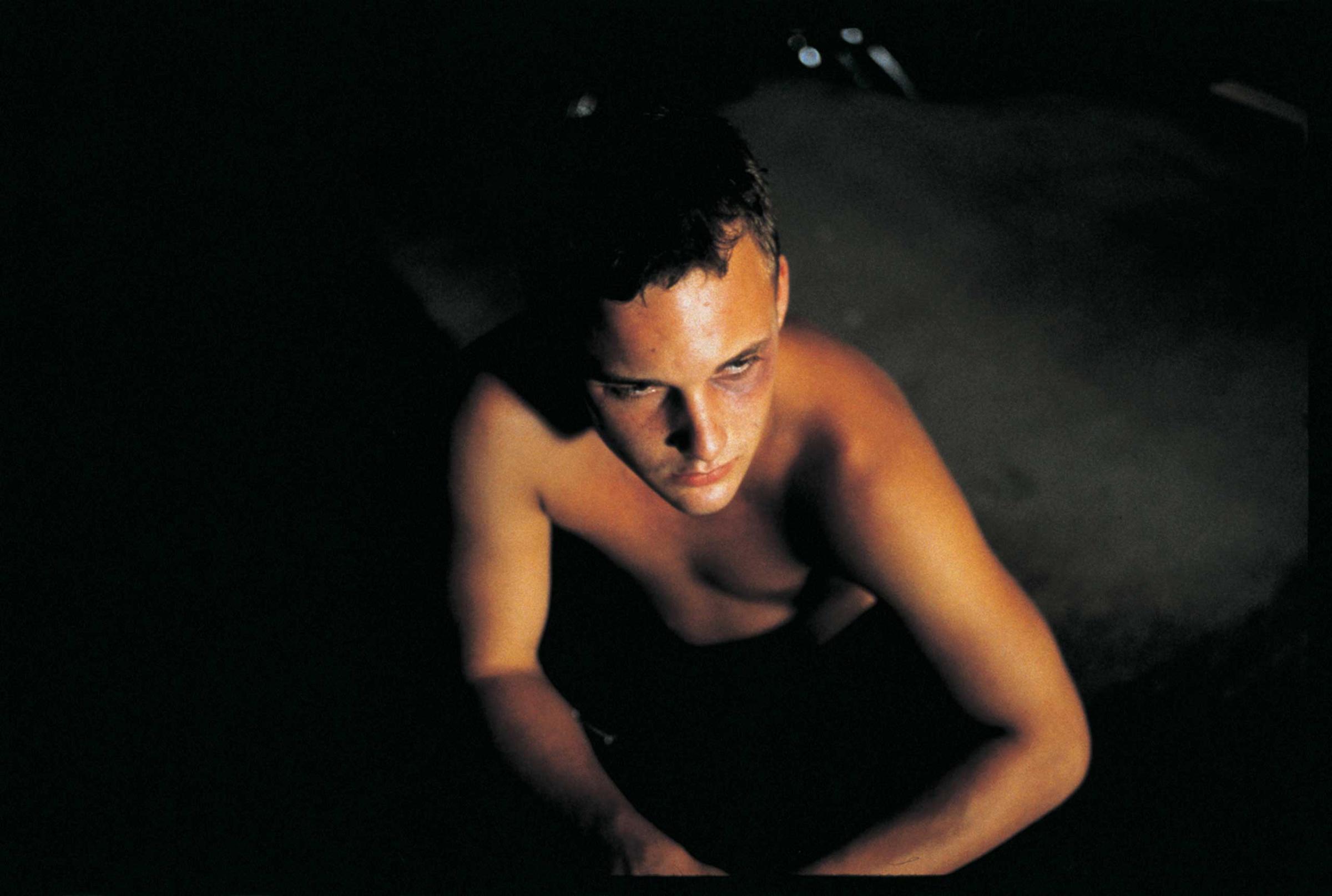

Bronson

This biopic tells the story of Charles Bronson (né Michael Gordon Peterson), a British criminal who is constantly getting into brutal fights, in prison and out, with guards and inmates. He’s been moved to dozens of prisons for bad behavior and spent much of his time in solitary confinement; the net effect is that he’s often called Britain’s most dangerous criminal.

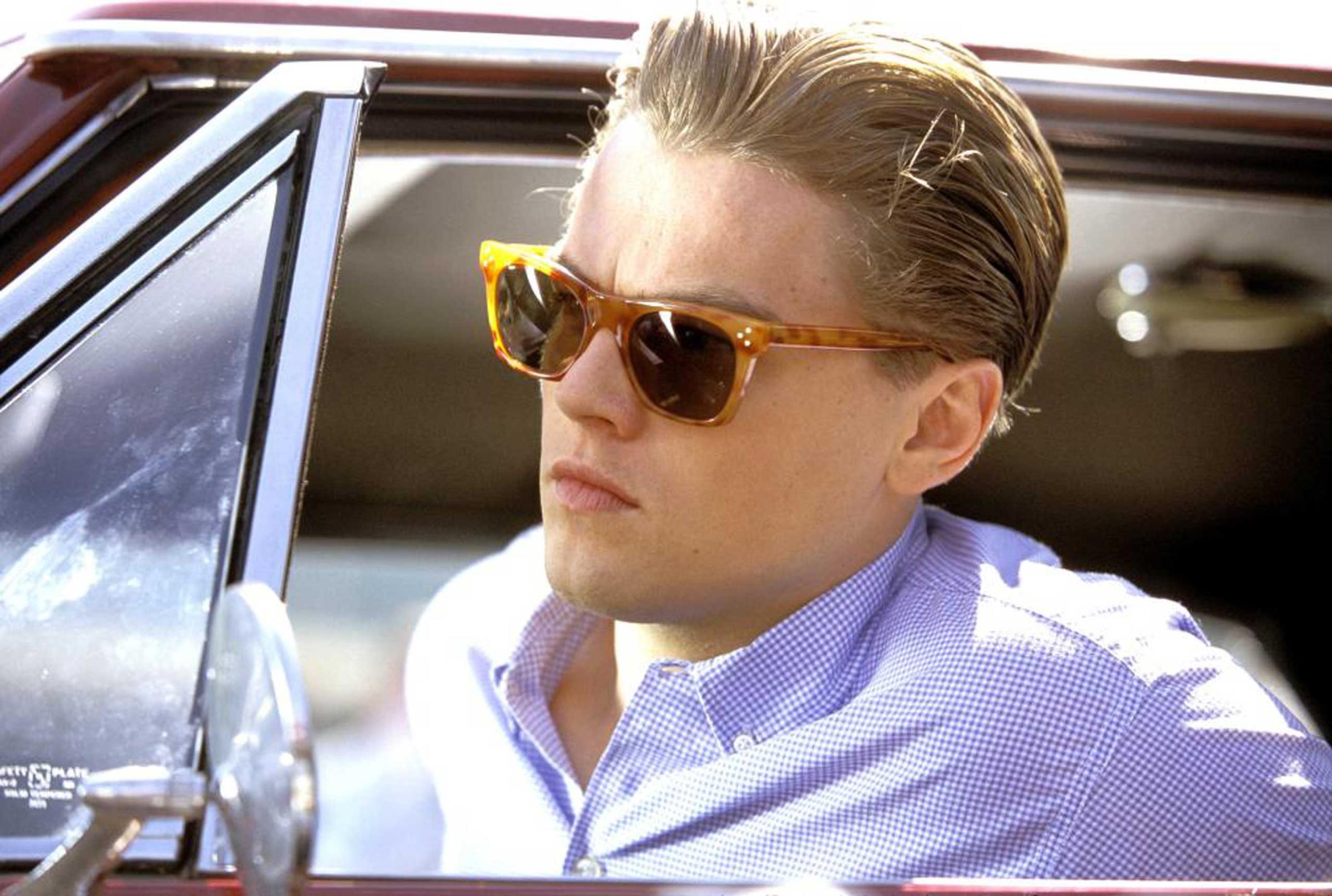

Catch Me If You Can

Leonardo DiCaprio stars as Frank Abagnale, a young con man who was able to make millions forging checks while posing as a pilot, doctor and lawyer. An FBI agent (played by Tom Hanks) pursues him until he’s captured. In the movie and in real life, Abagnale eventually becomes an FBI adviser, helping prevent exactly the kind of fraud he committed.

In Cold Blood

The film inspired by Truman Capote’s “non-fiction novel” tells the story of two outlaws, Richard Hickock and Perry Edward Smith, who murdered the Clutter family in their home in a quiet Kansas town in 1959. Both were hanged in 1965.

Black Mass

Based on the 2001 book of the same name, this movie sticks close to the facts of Irish-American mobster James “Whitey” Bulger (played by Johnny Depp) as he becomes an informant for the FBI during the 1970s. As in the film, the leader of Boston’s Winter Hill Gang used the protection granted by his status to cover the organized crime ring he continued to spearhead before going into hiding for 16 years. Now 86, he is three years into serving two consecutive life terms.

The Iceman

Michael Shannon plays the notorious hitman Richard Kuklinski, who was convicted of murdering five—though he later claimed to have killed more than 100 men—after decades of keeping his job as a contract killer a secret from his wife (played by Winona Ryder) and two daughters. The film alludes to Kuklinski’s abusive childhood, at the hands of both parents, and chronicles how his increasing sloppiness led to his eventual capture in 1986. He died in prison in 2006, at the age of 70.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com