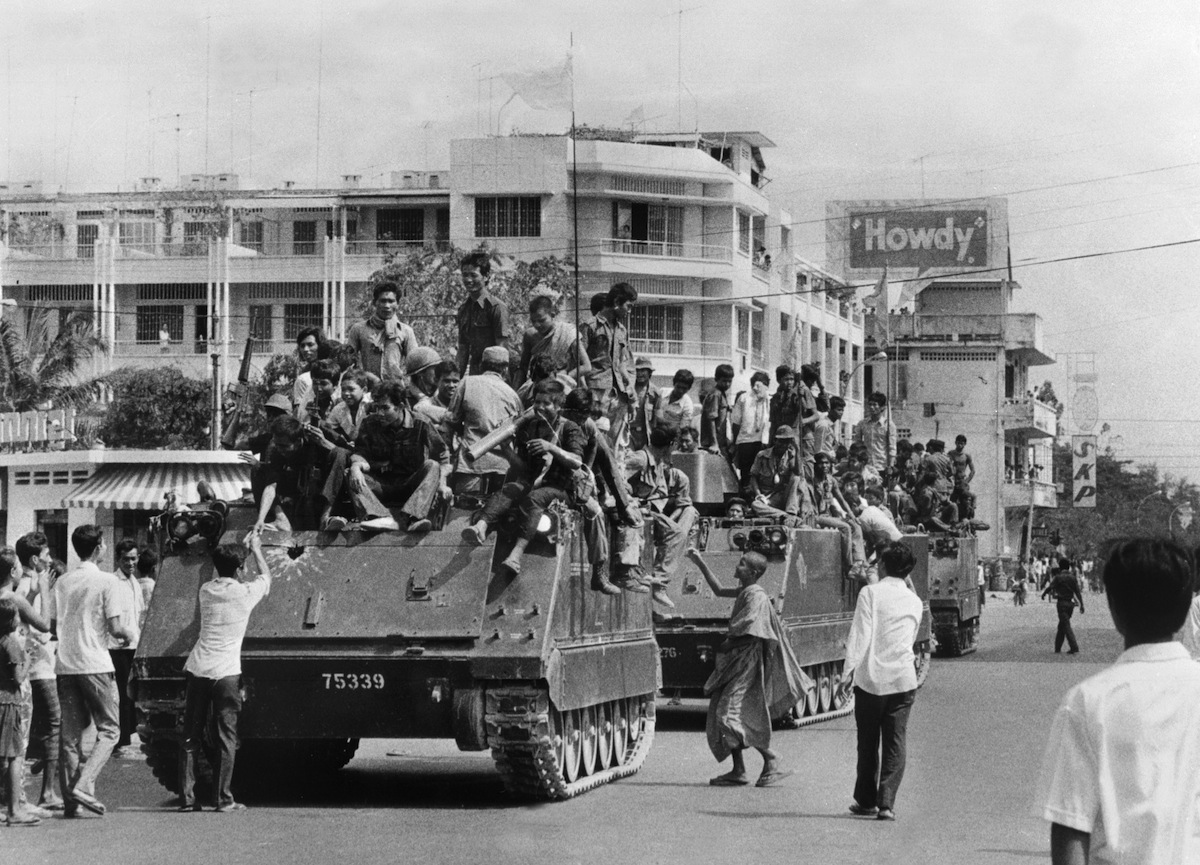

When the Khmer Rouge, the Cambodian Communist forces, seized the nation’s capital of Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975, it was no surprise. In the years since the nation had been drawn into fighting in the region, the insurgents had continued to gain power. With the end of the U.S.’s involvement on the horizon—that would come before the month was up—it seemed clear that Phnom Penh would fall sooner or later.

In fact, as TIME reported in the days after April 17, the very leaders who had pledged never to stop fighting seemed to know that there was no point in a last stand. The surrender of the Khmer Republic to the Khmer Rouge was, the magazine noted, the first time a capital city had fallen to Communist forces since Seoul in the early 1950s.

But, even though the regime change was no surprise, the world watched with apprehension to see what the nation’s new rulers would do. In that initial report, TIME noted that at first “there was none of the carnage that some government officials had predicted”—one of the main fears was that widespread retribution would be exacted—even though “there were, to be sure, some ominous notes.”

A few weeks later, it became clear that those fears were not misplaced. “The curtain of silence that has concealed Cambodia from Western eyes ever since the Khmer Rouge capture of Phnom-Penh on April 17 opened briefly last week, revealing a shocking portrait of a nation in torturous upheaval,” TIME reported. “Eyewitness reports by the few Western journalists who stayed on in the Cambodian capital after the closing down of the American embassy indicated that the country’s new Communist masters have proved to be far more ruthless, if not more cruel and sadistic in their exercise of power than most Western experts had expected.”

Those eyewitness reports, as relayed by TIME, told a tale of Phnom Penh (stylized with a hyphen at the time) being emptied of its inhabitants, as urban Cambodians were forcibly relocated to grow rice in the countryside, despite the fact that there would be no rice harvest for months and there was no other plan to feed them. Foreigners who took refuge in the French embassy were stuck inside the compound, with no running water, for nearly two weeks. Cambodians among them—many married to the foreign citizens—were removed from the group before the outsiders were driven by truck to the Thai border and allowed to walk across.

The journalists among the roughly 1,000 people who escaped in that way agreed to hold their stories until everyone who would be allowed to leave was out, but by mid-May they told what they had seen.

In the years that followed, the details, as they emerged, only got more harrowing.

In 1978, David Aikman, who had been a TIME correspondent who left Cambodia mere days before Phnom Penh fell, wrote in an essay that what had happened in Cambodia since that day was “perhaps the most dreadful infliction of suffering on a nation by its government in the past three decades”:

On the morning of April 17, 1975, advance units of Cambodia’s Communist insurgents, who had been actively fighting the defeated Western-backed government of Marshal Lon Nol for nearly five years, began entering the capital of Phnom Penh. The Khmer Rouge looted things, such as watches and cameras, but they did not go on a rampage. They seemed disciplined. And at first, there was general jubilation among the city’s terrified, exhausted and bewildered inhabitants. After all, the civil war seemed finally over, the Americans had gone, and order, everyone seemed to assume, would soon be graciously restored.

Then came the shock. After a few hours, the black-uniformed troops began firing into the air. It was a signal for Phnom Penh’s entire population, swollen by refugees to some 3 million, to abandon the city. Young and old, the well and the sick, businessmen and beggars, were all ordered at gunpoint onto the streets and highways leading into the countryside.

…The survivors were settled in villages and agricultural communes all around Cambodia and were put to work for frantic 16-or 17-hour days, planting rice and building an enormous new irrigation system. Many died from dysentery or malaria, others from malnutrition, having been forced to survive on a condensed-milk can of rice every two days. Still others were taken away at night by Khmer Rouge guards to be shot or bludgeoned to death. The lowest estimate of the bloodbath to date–by execution, starvation and disease–is in the hundreds of thousands. The highest exceeds 1 million, and that in a country that once numbered no more than 7 million. Moreover, the killing continues, according to the latest refugees.

Aikman’s essay confirmed that news of what was happening in Cambodia had reached the rest of the world, without a doubt—but, he wrote, the response confirmed that somehow knowing the truth didn’t mean believing it and responding appropriately. “In the West today, there is a pervasive consent to the notion of moral relativism, a reluctance to admit that absolute evil can and does exist,” he wrote. “This makes it especially difficult for some to accept the fact that the Cambodian experience is something far worse than a revolutionary aberration. Rather, it is the deadly logical consequence of an atheistic, man-centered system of values, enforced by fallible human beings with total power, who believe, with Marx, that morality is whatever the powerful define it to be and, with Mao, that power grows from gun barrels.”

Read the full 1978 essay, here in the TIME Vault: An Experiment in Genocide

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Where Trump 2.0 Will Differ From 1.0

- How Elon Musk Became a Kingmaker

- The Power—And Limits—of Peer Support

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Write to Lily Rothman at lily.rothman@time.com