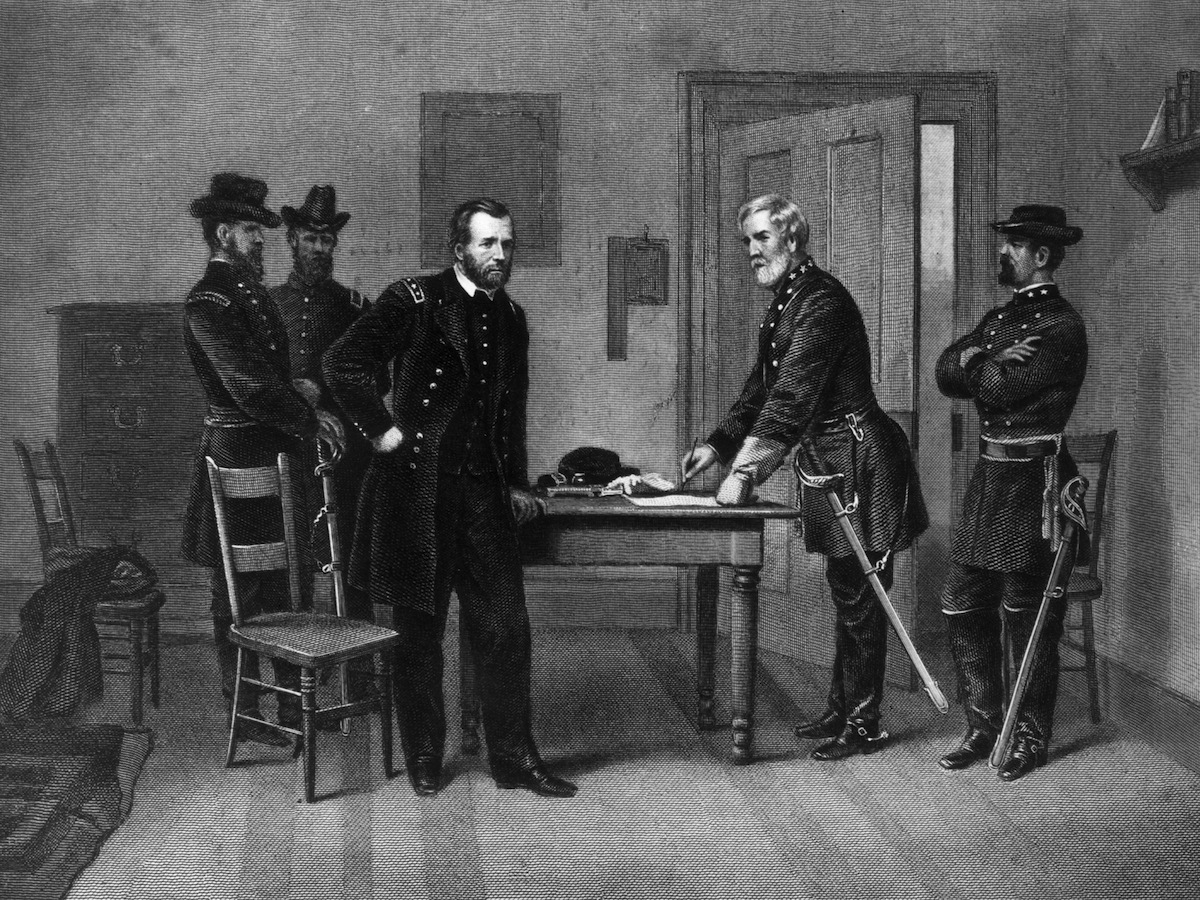

Confederate leaders may have believed they had built a unified nation in 1861, when they framed a new government and sent their troops off to war with hearty assurances of a quick and glorious victory. Amid the centennial observance of those events, however, Robert Penn Warren suggested that this judgement would have been premature; a sense of common southern identity had not actually been “born” at the beginning of the Civil War, but at the end, on April 9, 1865, when “Lee handed Grant his sword” at Appomattox. Indeed, many early enlistees had vowed to fight only “in defense of Virginia” or “my home state,” and some even restricted their allegiances to “the loved ones who call upon me to defend their homes from pillage.”

The challenge of instilling South-wide loyalties loomed even more daunting because Confederate identity would have to be constructed on the fly. Delegates who gathered in Montgomery in early February 1861 managed to draw up the constitutional and governing framework of the Confederate States of America in only five weeks. Scarcely five weeks later, their brand new nation-state was plunged into a war that many of them had persuaded their constituents—and perhaps even themselves—would never come.

Reluctant to acknowledge the hard truth of their own Vice-President Alexander Stephens’ declaration that slavery was the fundamental “cornerstone” of their new nation’s existence, Confederate propagandists could devise no more compelling raison d’être than the explanation that, rather than actually repudiating the Union, they were seeking simply to resurrect its founding principles of state sovereignty and federal restraint. Thus, the Confederacy’s identity would be assembled largely from recycled components, appropriated from the nation its people had just abandoned and would soon be fighting. The first was a constitution that, save for a wrinkle or two, basically replicated the one that, as citizens of United States, the Confederates had once sworn to honor and protect. Having co-opted the founding document of the nation they were leaving, they also kidnapped its founding father by placing a likeness of George Washington on the Great Seal of the Confederacy as well as on its currency, bonds and postage stamps. Finally, in the “Stars and Bars,” with its circle of white stars on a blue field surrounded by bands of red and white, the Confederates adopted a national flag so easily confused with “the Stars and Stripes” that it was quickly banned from the battlefield. In view of all this symbolic copycatting, the number of southerners who actually continued to celebrate July 4th well into the hostilities seems a bit less surprising.

Although secessionist firebrands like Henry Lewis Benning had led their fellow southerners out of the Union under the banner of “state rights,” their new government was actually no more a decentralized “confederacy” than their old one, but rather the “consolidated Republic” dominated by slaveholders that Benning had envisioned from the start. Even early on, when the military effort was going well, the exigencies of wartime demanded centralized control of production and distribution, leading quickly to complaints over shortages, inefficiency and corruption that would grow increasingly strident as the tide of war turned.

From the first, however, the outmanned but valiant and resilient Confederate fighting men commanded the popular loyalty that the Confederate government had failed to inspire. This transfer of allegiance came through in the common habit of displaying not the national flag, but the starred St. Andrews Cross that had supplanted it on the battlefield, where, General P. G. T. Beauregard noted, it had been “consecrated by the best blood of our country.” Notably, this flag conveyed a sense of commitment to military success, but not to the unpopular government.

Within days of Lee’s surrender, poet-priest Father Abram Ryan immortalized that now “Conquered Banner,” which, though furled at Appomattox, was both “wreathed around with glory” and destined to “live on in song and story.” Ryan’s weepy ode would be pressed into service repeatedly in the years to come in order to rally white southerners yet again to the defense of their racial institutions. This time, however, instead of the decidedly parochial, localist constituency that had confronted them in 1861, postbellum southern nationalists could draw on a more regionalized mindset. Its roots lay in the experience of men who had not only fought shoulder-to-shoulder with comrades drawn from distant states, but who had also in many cases traversed a vast geographical area, inhabited by people whose lives and values seemed strikingly similar to their own. These men and their descendants, noted W. J. Cash in his 1941 classic, Mind of the South, were now more likely to respond to the word “southern” with an emotion once reserved solely for “Virginia, or Carolina, or Georgia.”

Though difficult to pinpoint, the birth of the South as what Cash called “an object of patriotism” likely came somewhere in the course of a fierce, four-year “conflict with the Yankee.” Warren would surely have been justified nonetheless in dating its confirmation to the ceremonial acknowledgement of the Confederacy’s bitterly painful but ultimately unifying failure, 150 years ago this day at Appomattox.

Historians explain how the past informs the present

James C. Cobb is Spalding Distinguished Professor of History at the University of Georgia and a former president of the Southern Historical Association.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com