“Our country is made for long trips,” the photographer Stephen Shore once mused, a statement proven true in The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip published by Aperture next month.

As its writer David Campany explains, the idea of the road as a place of freedom and discovery has been with us for years. In fact, it was the 19th-century poet Walt Whitman who gave us the admiring phrase “the open road.”

For photographers, perhaps the most mobile of all artists, the road is a natural home.

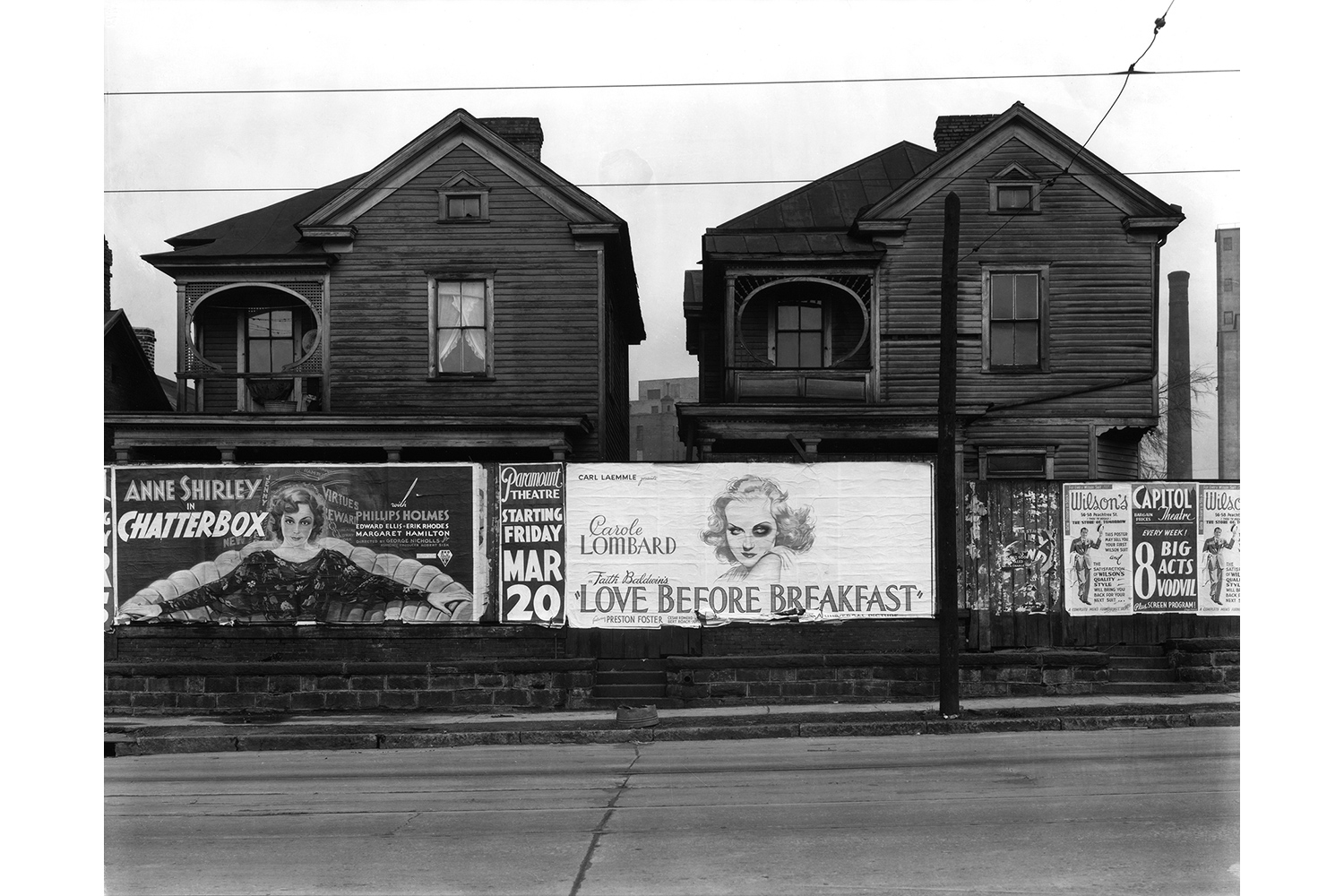

The first masterpiece of the road trip genre was Walker Evans’ 1938 MoMA exhibit and book “American Photographs.” Made over the course of a decade of travel across the eastern half of the US, it is a plain-spoken but quietly artful statement about everyday people, architecture and signage during a time of hardship.

In its early years, the possibilities of the road seemed endless. “Futurama: Highways and Horizons”, an exhibit at the 1939 New York World’s Fair (financed by General Motors), envisioned a utopia where workers zipped along mega-highways between the industrious city and the sparkling suburbs.

Indeed, the short term transformations were breathtaking. The country built countless news cars and roads to drive them on, as well as innumerable fast food joints, motels and gas stations.

But it would take years to understand the deeper changes this would bring to the cultural landscape of the country.

Interstate highways helped mobilize and mix Americans as never before, and a national monoculture slowly overtook regional subcultures.

Artists would spend much of the 50s, 60s and 70s responding to this. As Campany writes, “boredom and repetition became the new muses.” Ed Ruscha’s 1963 book “Twentysix Gasoline Stations” is a deadpan index of—you guessed it—26 gasoline stations. (Ironically, Campany notes, “today, people love that book for its period charm!”)

Meanwhile, soaring traffic fatalities, pollution and congestion helped further tarnish the myth.

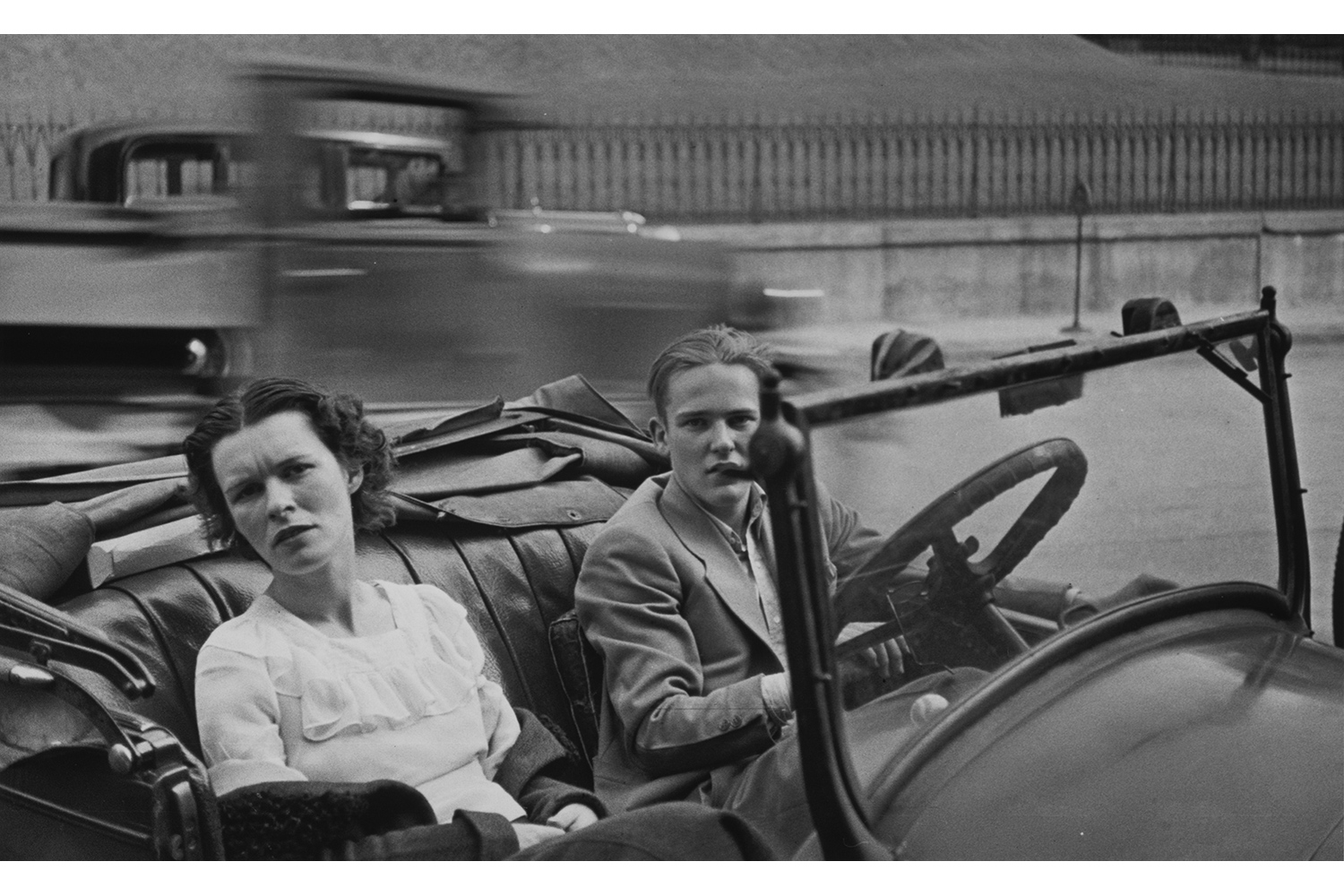

The anxiety and alienation of the new age found its ultimate expression in Robert Frank’s 1959 road trip book “The Americans”, a highly personal response to the commercial excess, racial animosity and loneliness he saw in his adopted country.

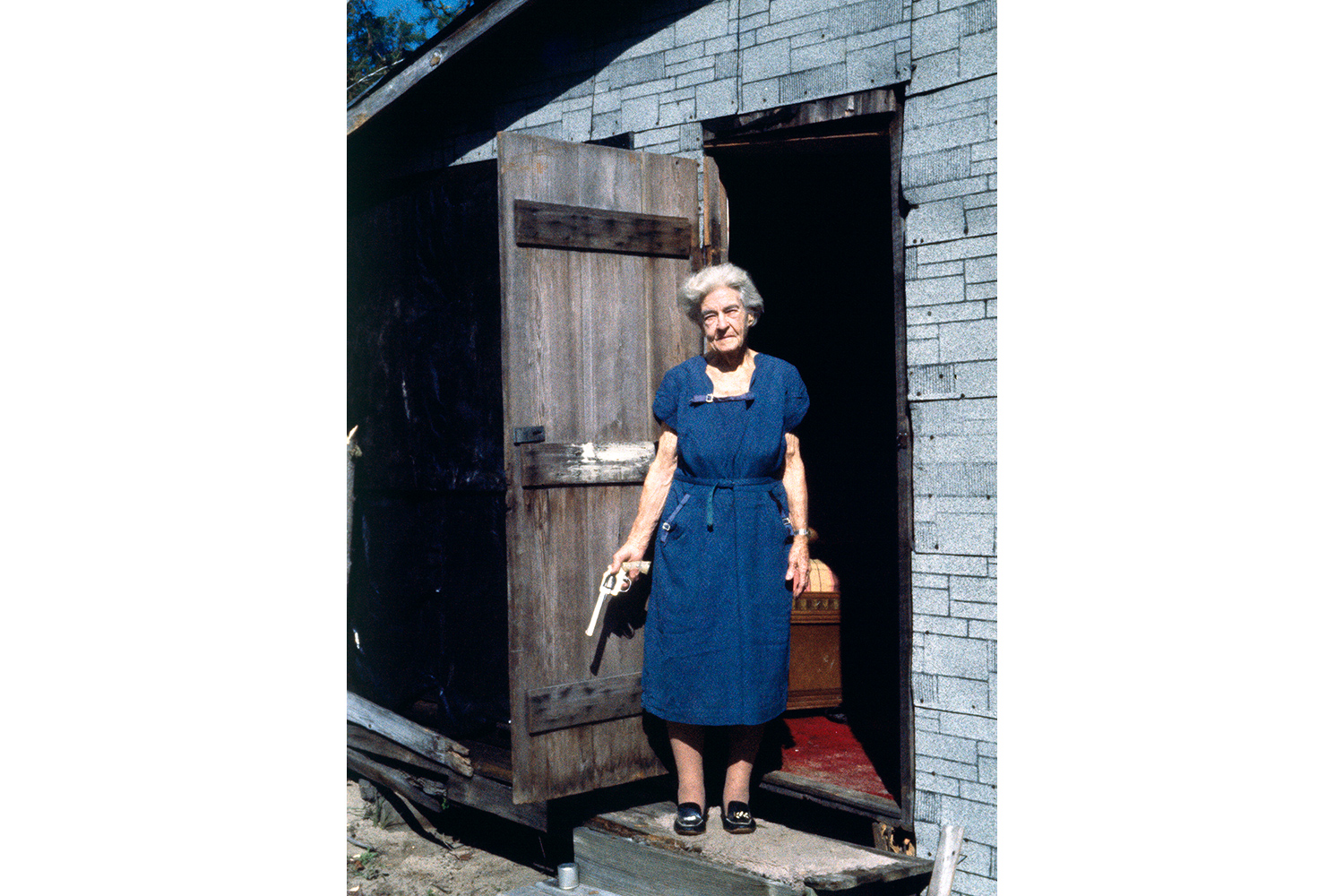

By the 1970s and 80s, the grand idea of the road had shrunken into cliche. In the work of both Stephen Shore and Mitch Epstein, Campany writes, “we sense both the photographer and his subjects feeling their way through America as image.”

Today, he says “even the more classically minded contemporary photographers [like Vanessa Winship, Alec Soth and Justine Kurland] are […] fully aware that to even set out on the road with a camera is to summon a well-established history of American photography.”

These photographers include Taiyo Onorato and Nico Krebs, who use humorous and absurd interventions to toy with our notions of the road. And even the artist Doug Rickard knows the history of the genre well, even though he doesn’t actually take road trips, using Google Street View instead. “All is here,” Campany writes of the work, “from the early thrills of what a new technology can show of familiar and strange subjects, to the existential crises, the euphoric interludes, the unexpected moments of poetic grace and polemic, and the unknown.”

Thus, in this genre—like on any of America’s epic highways—a bend in the road reveals not an end, but yet another vista.

The Open Road: Photography and the American Road Trip is published by Aperture.

Myles Little is an associate photo editor at TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com