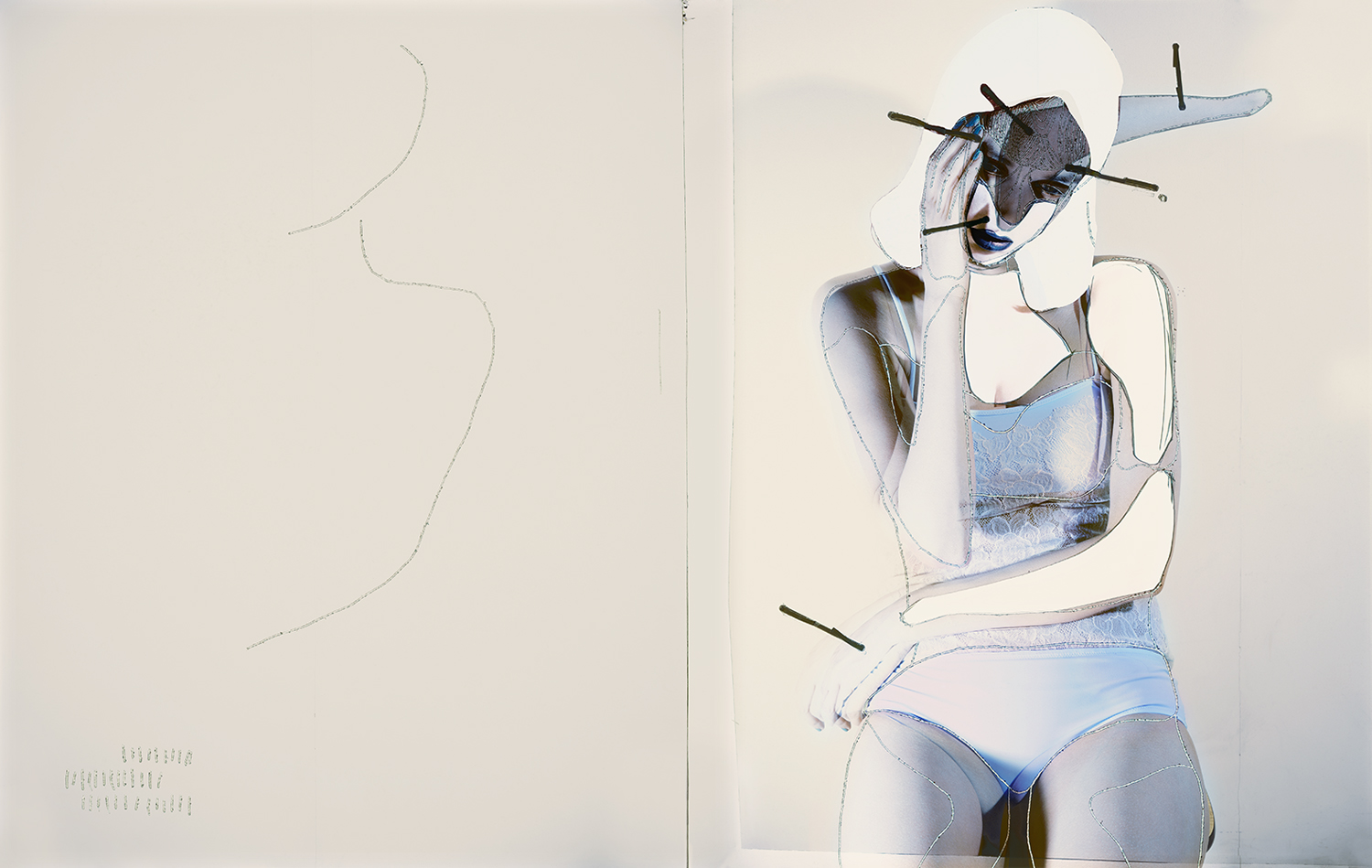

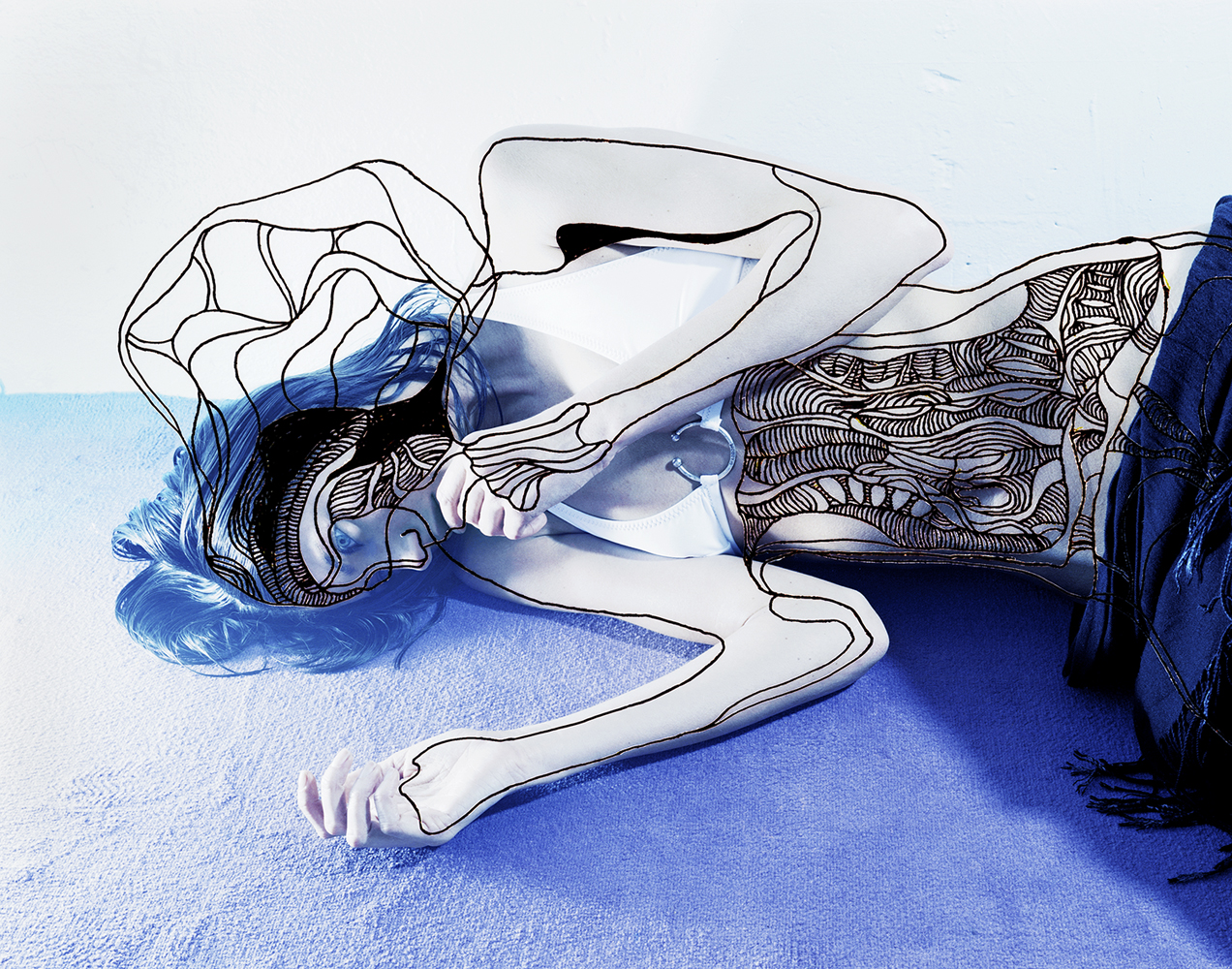

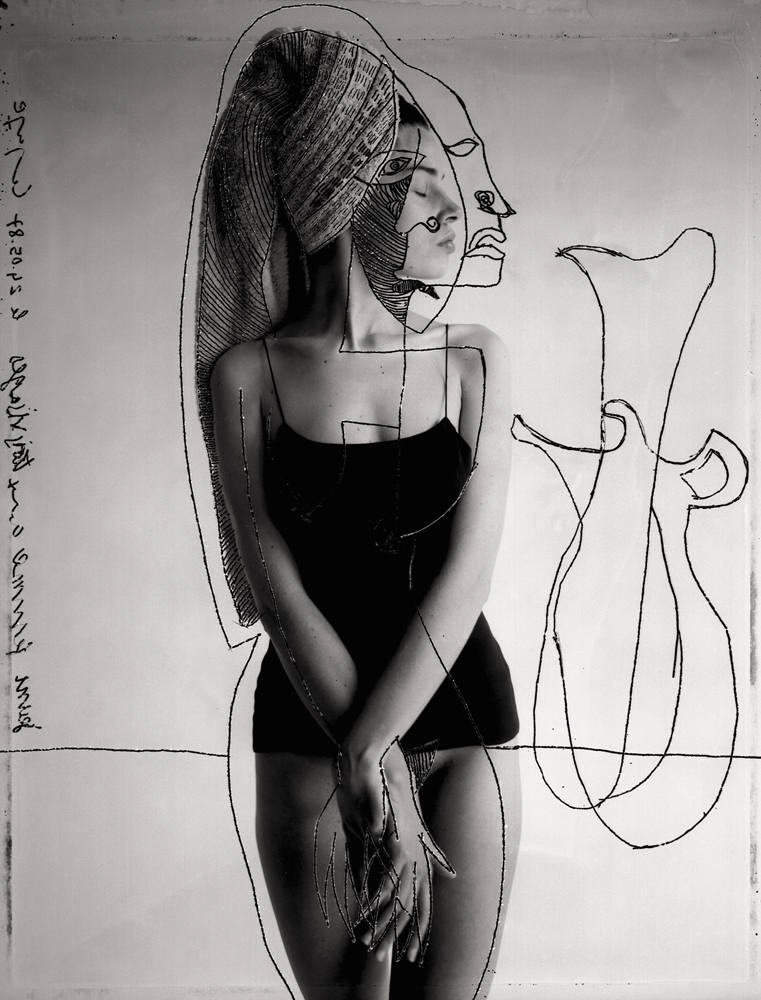

Jean-Francois Lepage is a photographer whose working methods are closer to that of a painter. His paradoxically alluring and disquieting photographs bare evidence to a process in which he physically cuts, draws and works into their surface to intricately evolve and brutally deconstruct the original image.

“I always thought photography was not only about taking an image of someone or something, showing an instant,” he tells TIME. “I think that unconsciously I try to extend the time, to prolong the moment of the shooting when I’m working later on my images. Cutting, engraving this inanimate matter, using staples to fix the pieces of film together – it is certainly a way to refuse the death of this instant.”

Lepage’s intuitive approach to the image-making process is cathartic. “I’m like a surgeon who faces his patient with lucidity and commitment but with the absolute certitude that the only person I can really save is – myself.”

Over the past three and a half decades, since his first published images appeared in Depeche Mode, he has chosen to work sporadically for editorial and advertising clients, while taking time—including a 13-year period of abstinence from commercial environs—to pursue his art through painting in a purer form.

While Lepage’s early photographs were visceral and dark—including sexual images that could not be reproduced in a commercial editorial context—he found like-minded collaborators including art director Grégoire Philipidhis at the short lived, but highly influential Jill magazine in Paris. Philipidhis embraced his work and gave him the freedom to express himself within its pages.

Subsequently, Lepage has maintained his distinctive voice as his imagery has evolved. “I would compare my creative process to a never ending spiral. I do have different periods that are representing my whole personality,” he says. “I need this raw part to my work as well as the poetic approach which is also important for me.”

After his self imposed exile from photography, Lepage returned with a new approach, moving outside to work on a series of stories for AMICA magazine. In his work, Lepage intentionally shows the source used to light his subjects, and to “compose and balance his light with the Sun to create a new perspective.”

As Lepage moved away from the monochromatic palette of his earlier work, a dark undercurrent prevailed. “When I look at my images I see overly bright colors that are hiding our sadness – people who are wearing masks to reveal themselves – lonely characters strong and peaceful – mutilated forms that show human beauty and eyes turned inward to better understand our world.”

More recently he has begun to pull away from fashion once more. He is currently making new work, recycling photographs from his archive to build new pictures—finding his palette by cutting up outtakes from his old shoots of now discontinued 8×10, 891 Polaroid from the 1990s, to make work which he describes as still “photographic but more abstract.”

“It is like in life, some people are experimenting when they are young and they become more and more conventional with time [while] a few others will always continue to experiment,” he says.“I think the world is always limiting for people who want to propose something different. On the other hand it’s also because the world is limiting that they can experiment.”

Jean-Francois Lepage is a photographer basedin Paris. His work is widely seen as blending elements of cinema, surrealism, and haute-couture.

Phil Bicker is a senior photo editor at TIME.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- How Far Trump Would Go

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- Saving Seconds Is Better Than Hours

- Why Your Breakfast Should Start with a Vegetable

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- Welcome to the Golden Age of Ryan Gosling

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com