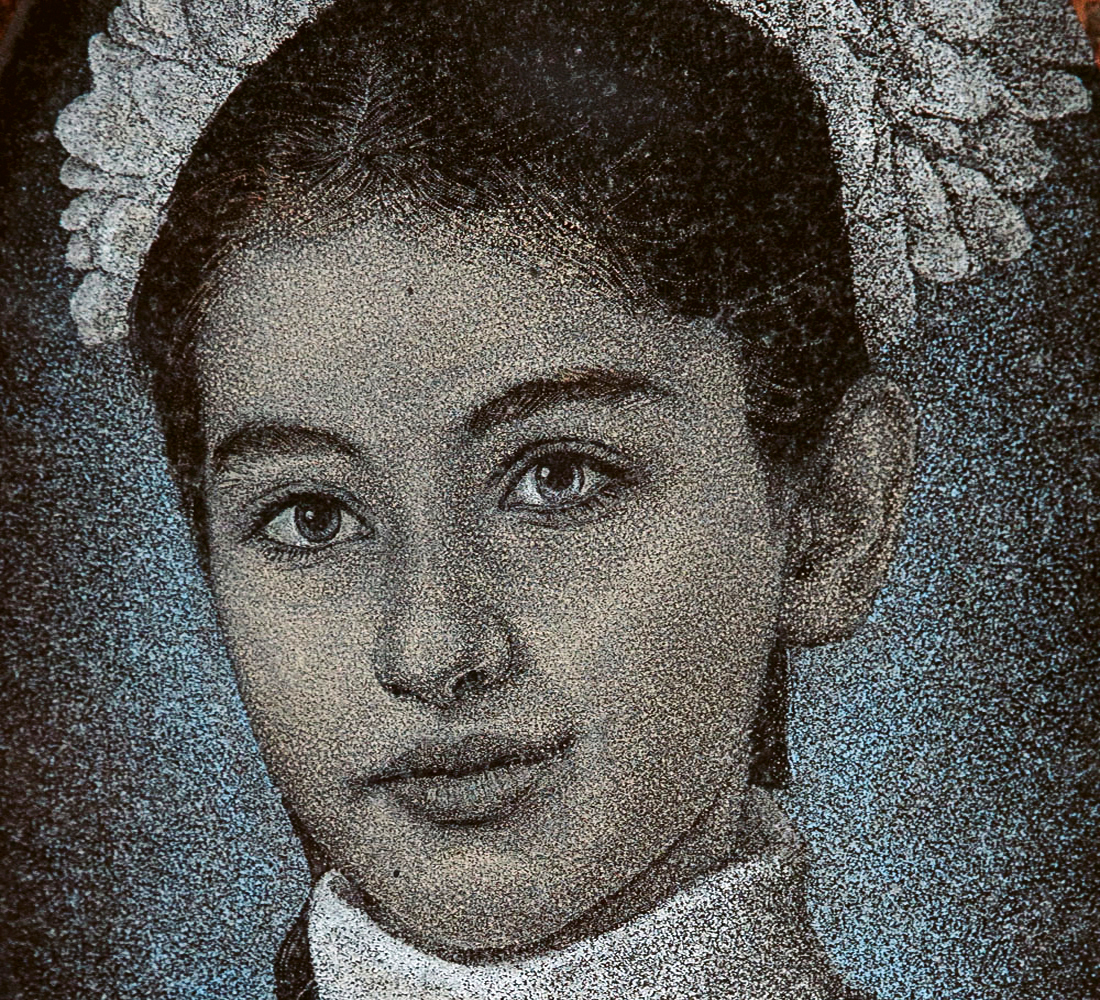

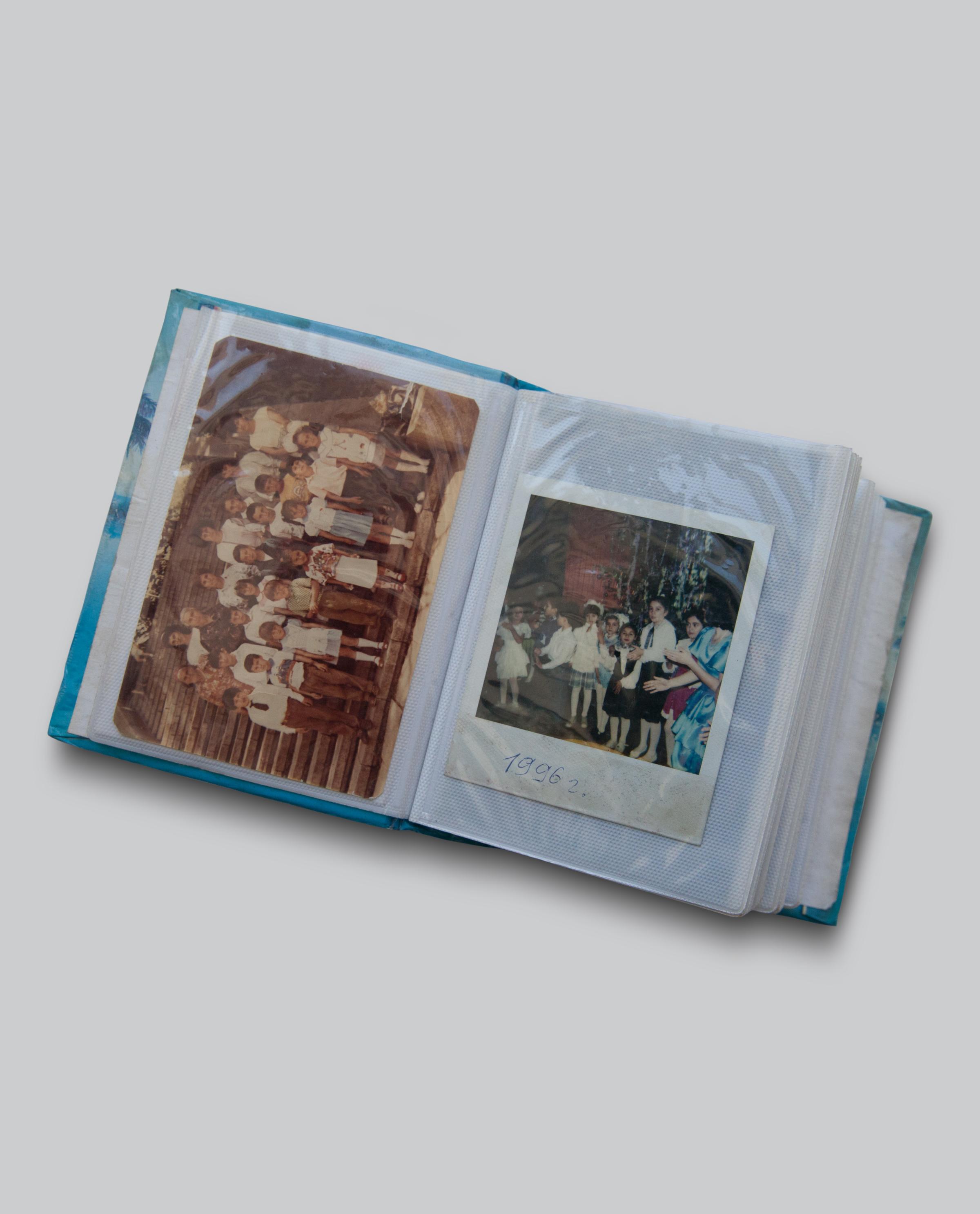

They were dressed in their best, little girls in spotless white ruffled pinafores and boys in freshly pressed dress shirts buttoned to the collar. It was September 1, 2004, the start of school, a cause for celebration throughout Russia.

When the first shots were fired, 11-year-old Zarina Albegava mistook them for fireworks. She is 21 now, but still has trouble talking about what happened next.

“I don’t want to remember,” she says.

Albegava, her sister Zalina, nine, and around 1,200 others were taken hostage during a back to school celebration in Beslan, in the Russian republic of North Ossetia. Two days later around 330 of them were dead, more than half of them children. Zalina was one of the dead.

It was the worst terrorist attack Russia had ever seen, a gruesome footnote to the two wars that Chechnya fought for independence in the 1990s. Even after Russia finally subjugated the Muslim republic in 2000 and installed a loyal warlord to control it, the conflict continued in the form of an Islamist insurgency whose fighters have staged suicide bombings as far afield as Moscow for years. Beslan is considered one of the conflict’s greatest travesties against the innocent. But a decade later the world has moved on. Residents of this little North Caucasus town have not, partly because important questions remain unanswered: How many terrorists escaped? What caused the explosion that lead to the storming of the school?

It was this sense of loss and longing for answers that attracted documentary photographer Diana Markosian to Beslan. Of Armenian heritage, Markosian, who is 25, often confronts the lingering effects of loss in her work, especially childhood losses. Markosian lost her own father and country, in a way, at seven when her mother moved her and her brother from Russia to Santa Barbara, and their father remained in Moscow. They never talked about her father after that and it was 15 years before she saw him again. When a Beslan survivor told her about the split of his life into “before” and “after” she understood.

“When I was separated from my dad, that’s exactly what happened, I had this experience of being torn apart from the life I had always known,” she tells TIME.

Having spent her early childhood in Armenia and Russia, Markosian also understood the significance of September 1. She still has the yellow and green Bambi backpack her father gave her for her first day of second grade. She hadn’t seen him in weeks, but he was there for the first day of school, holding hands with her mother and brother as they all walked to school.

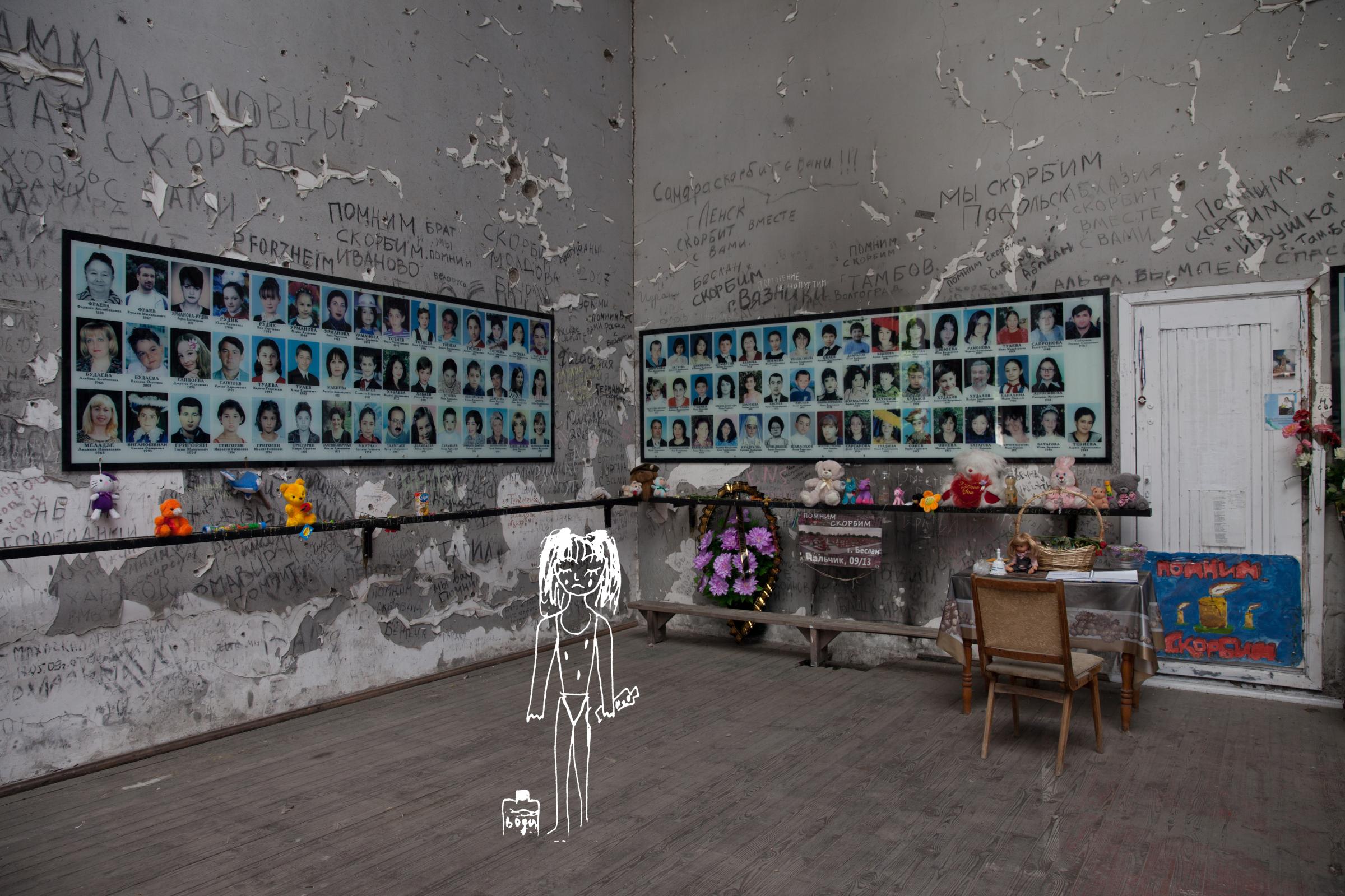

As a young journalist in Moscow, Markosian passed through Beslan regularly en route to Chechnya. Sometimes she stopped at the school. It served as a monument to the siege, a battle-scarred structure filled with uncapped water bottles the children probably needed desperately during captivity. The hostages were corralled in an airless gym booby-trapped with explosives. For most, there was no water or food after the first day. On the second day the Chechen-speaking captors demanded Russia begin to remove its troops from Chechnya. On the third day there was an explosion and Russian forces stormed the building. In the ensuing firefight only one of 30 or so terrorists was captured alive, later sentenced to life imprisonment.

The shadow of Beslan followed Markosian until she decided to revisit the tragedy through her work. She arrived, she says, looking for the remains, “the direct aftermath of the event.”

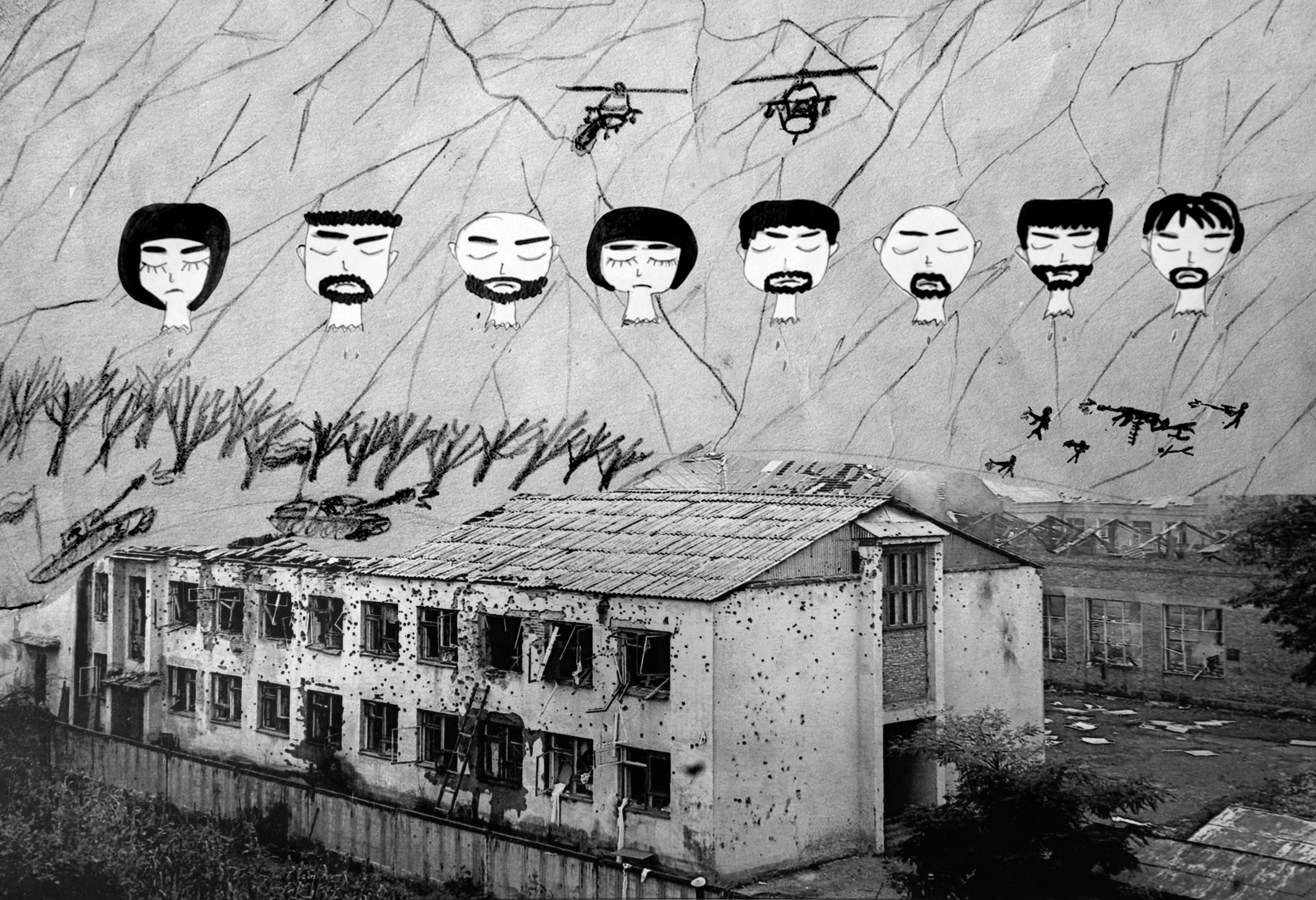

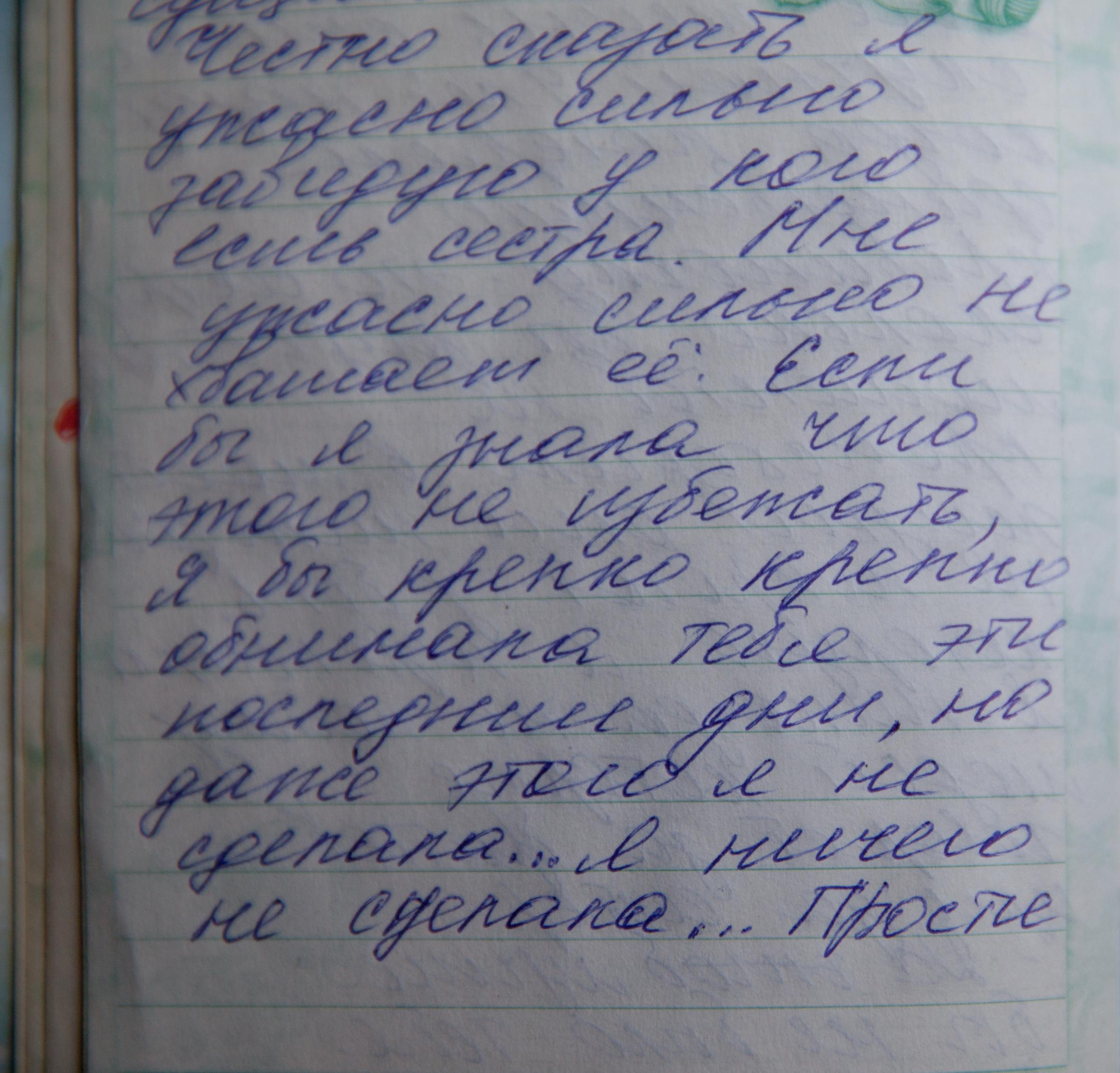

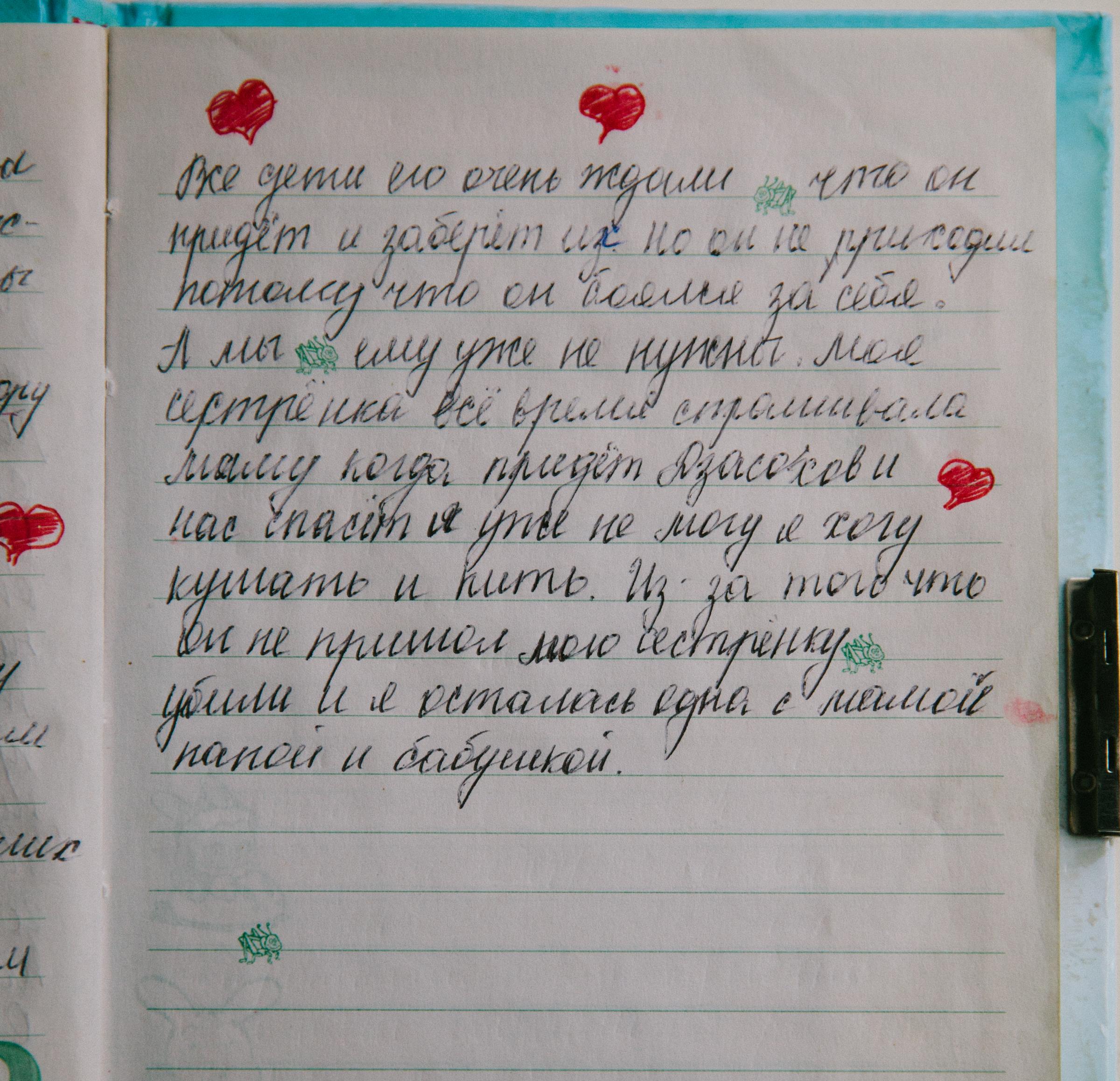

She found children’s drawings.

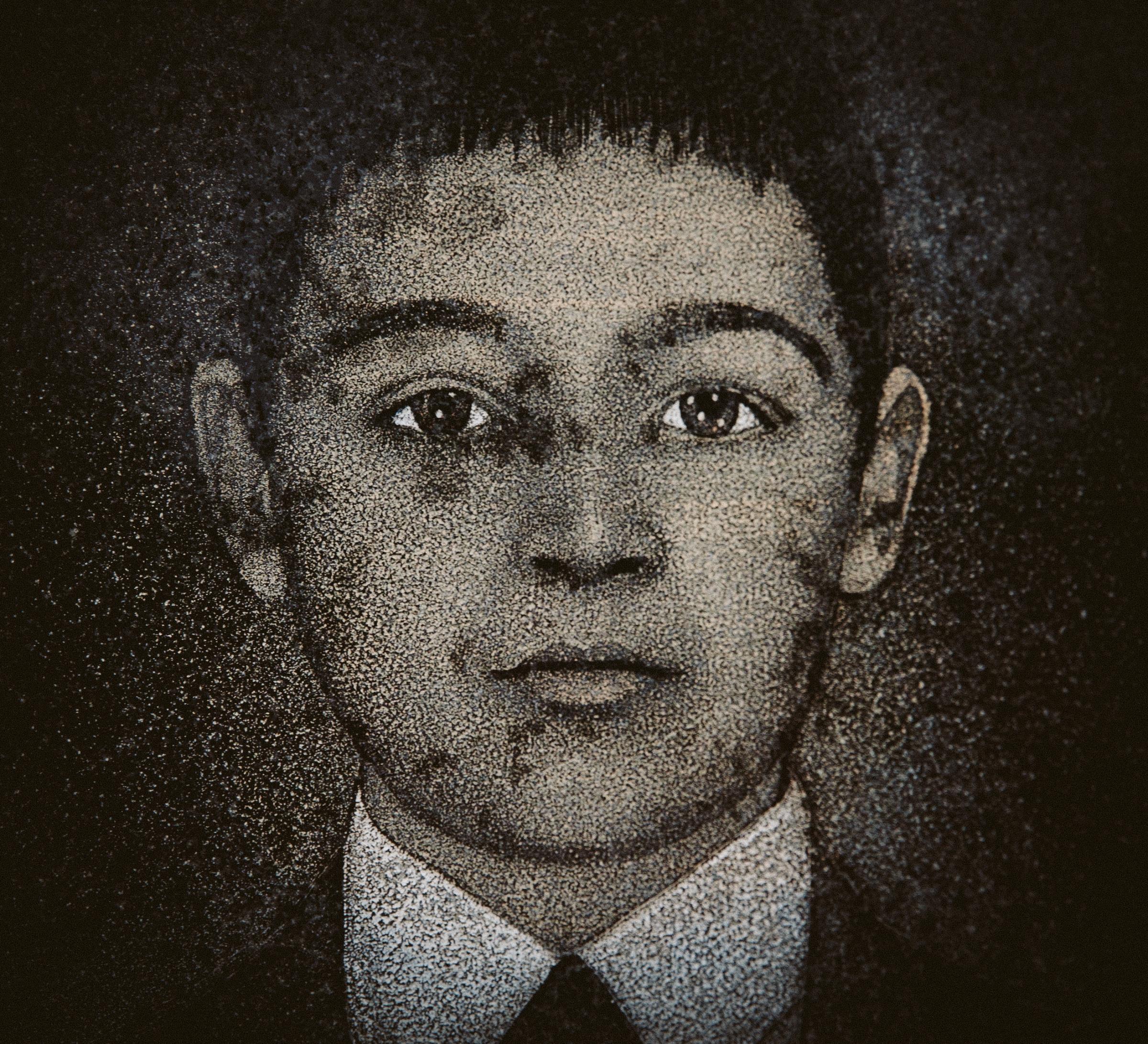

They showed her what she couldn’t capture in photos, drawings of their dead fathers. The men were the first to be killed. Around 20 were shot execution style in a room where Russian literature was once taught. The corpses of fathers who had come to celebrate their children’s first day of school were thrown out the window and left to rot in the sun.

“I wanted this body of work to be collaboration,” says Markosian. “This is their story, their experience, and I wanted them to take part in it.”

Markosian had been resisting the constraints of traditional photojournalism, the distance between subject and photographer. The brutal, simple pictures made by the children in the tragedy’s aftermath combined with her own images allowed her to bridge the gap. Images of barely clothed men, women and children holding bottled water remain as unchanged as the rooms they inhabit in Markosian’s photographs, rooms decorated with bullet holes and peeling paint. On a picture of a sixth grade class she has the survivors write messages to their deceased classmates.

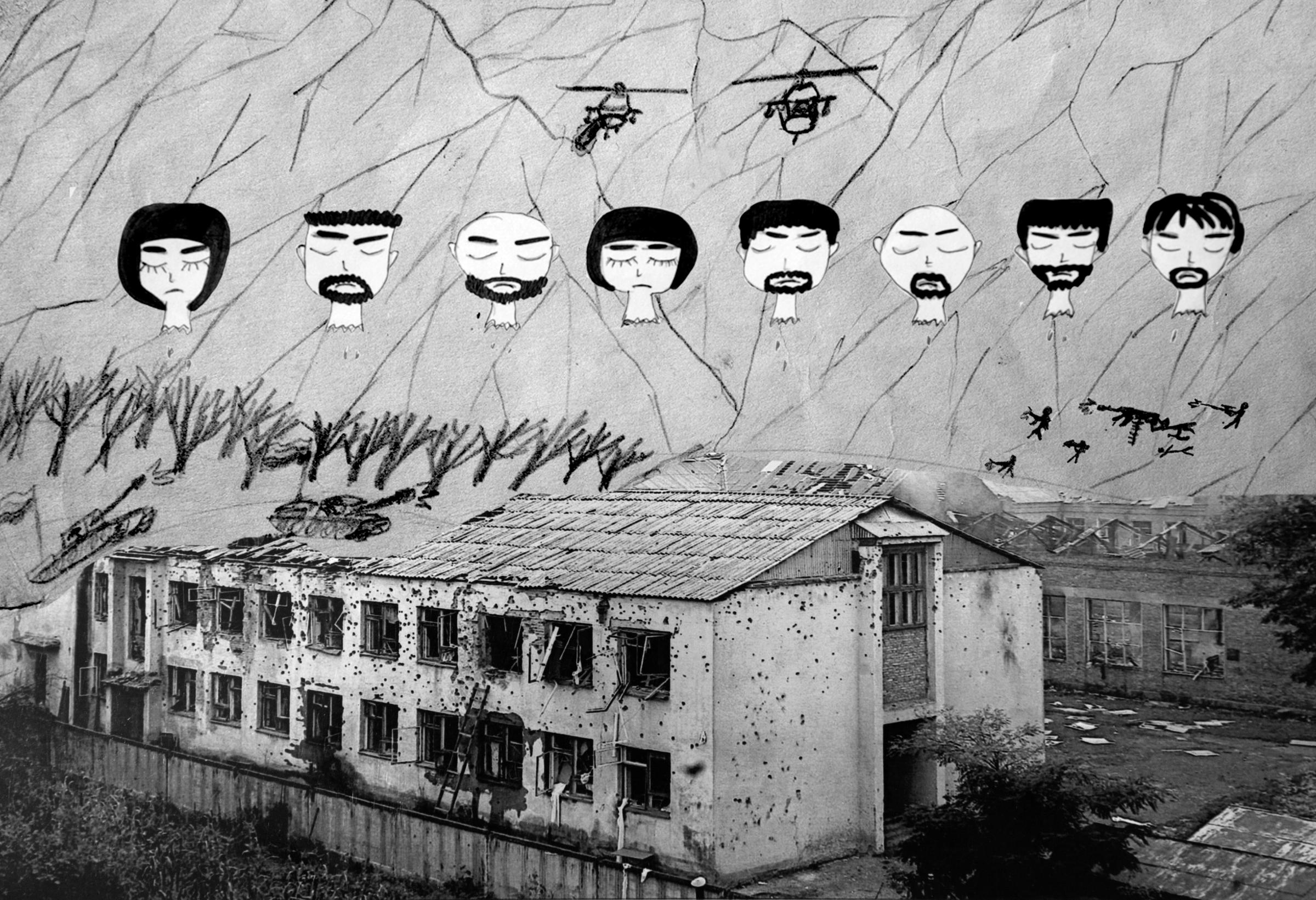

The children, now young adults, journeyed with her back to the school, sometimes for the first time since the tragedy. In silence, with their eyes shut, they remembered. Then they shared those memories with Markosian: the window through which their mother was shot, the spot next to them where their sister died, the classroom where they studied.

Markosian captures the survivors’ visual discomfort at being trapped in a place they have never been able to escape through portraits taken in the school. Other shots show the artifacts the dead left behind, a new shoe, a bloodied undershirt, a child’s untouched bedroom. For Beslan time has not provided resolution.

“The idea that time heals does not hold true for these families,” says Markosian. “Time heals? No, it doesn’t.”

Diana Markosian is a photographer based in Chechnya. Her previous photo essay, also published on TIME LightBox, Inventing My Father will be exhibited at Blue Sky Gallery in Portland in January 2015. See more of her work on her website.

Katya Cengel is a freelance writer. Follow her on Twitter @kcengel.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com