Welcome to TIME LightBox’s curators series, which invites top photography curators from around the world to present and discuss photography of their choosing in an effort to learn more about their curatorial preferences and the path from individual images to full-fledged exhibitions. In this edition of the series, TIME invited Lisa Hostetler, of the Department of Photography at George Eastman House, to talk about her archival survey of World War I and the process of unearthing little-known images of a world at war.

On July 28, 1914, Austro-Hungarian troops invaded Serbia in retaliation for the assassination, one month earlier, of Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria and his wife, Sophie, by Yugoslav nationalist Gavrilo Princip. Entangled alliances and colonial imperialism among key European powers—Germany, England, France, Russia and the Ottoman Empire—led to war on an unprecedented scale.

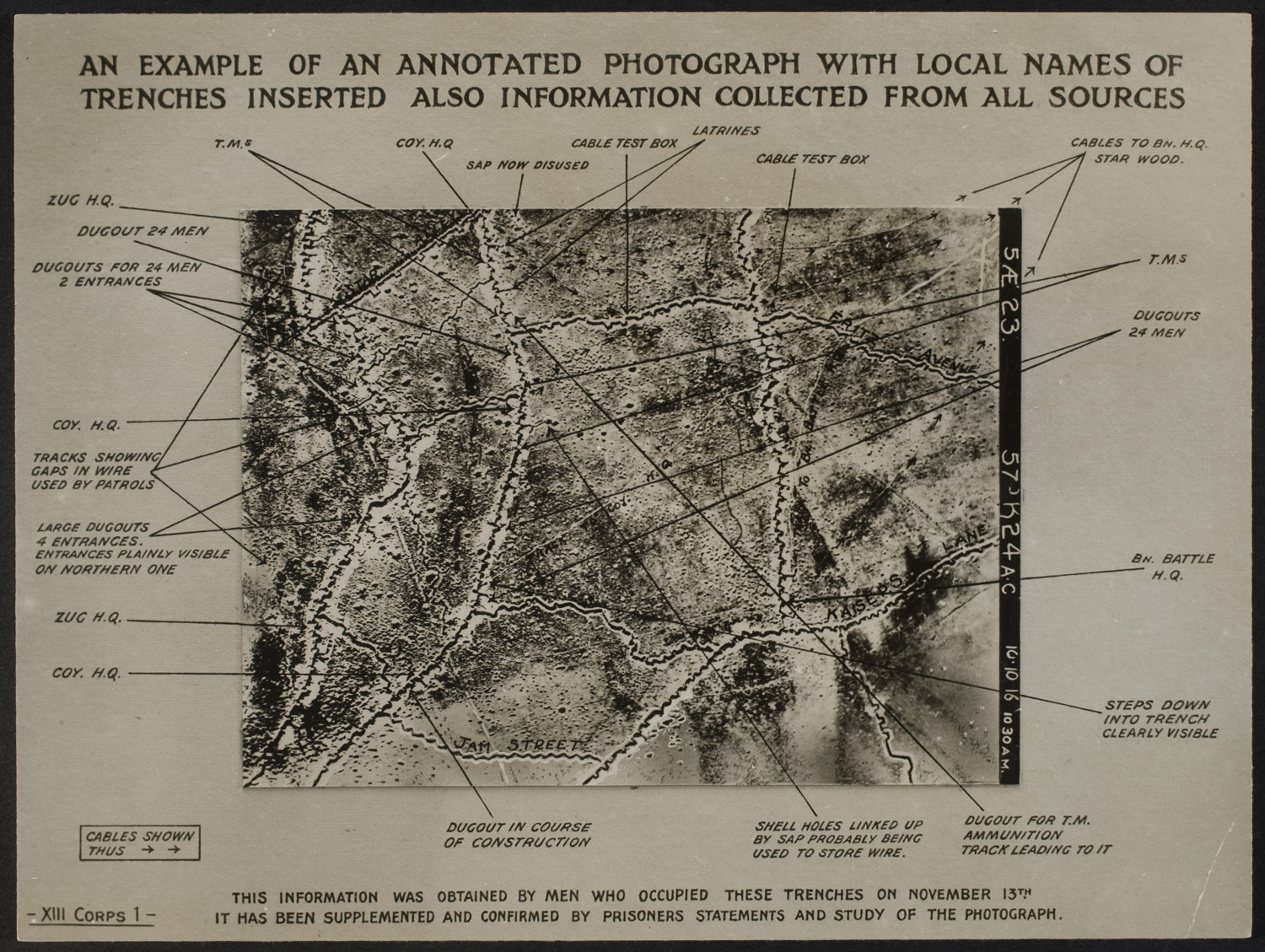

Technological advances in weaponry demanded new military strategies, but the learning curve was steep. This, in addition to the implementation of newly available intelligence-gathering techniques made possible by modern photography and aviation, led to a staggering number of casualties: 16 million dead — including seven million civilians — and 21 million wounded.

The Great War fundamentally changed popular perceptions not only of war, but of the social and political systems that created an environment in which war was almost inevitable. During the late 1910s, ’20s and ’30s many questioned the status quo, resulting in cultural and political phenomena—the Bolshevik Revolution, Weimar Germany, Surrealism, the Lost Generation, the New Vision in photography and the acceleration of the picture press—that radically altered the texture of everyday life in the West.

These and other interwar developments have been widely studied, but I wondered what it was like for civilians and military personnel during the war years amid the upheaval.

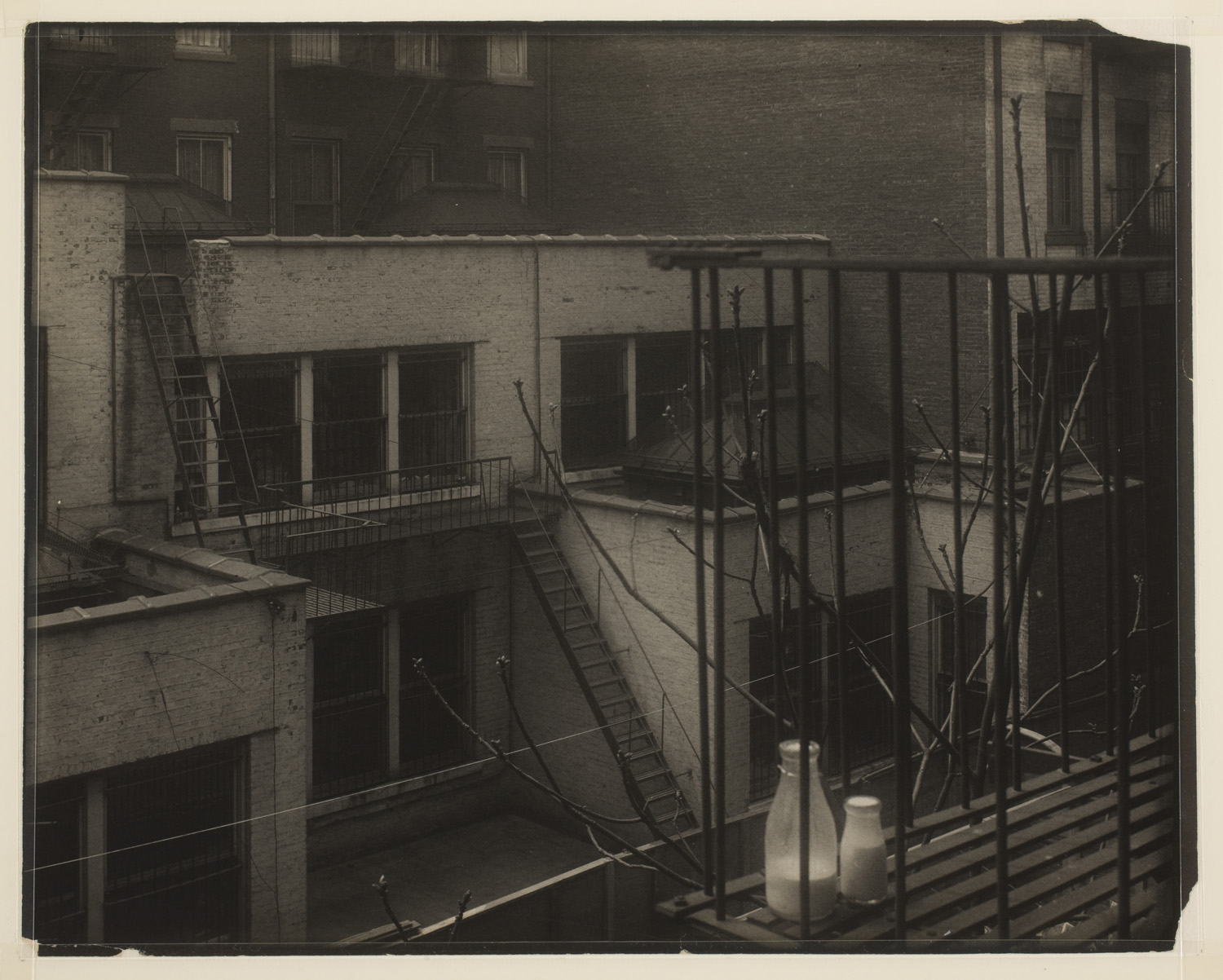

Since photographs are made by all kinds of people for all kinds of purposes—and because photographs automatically embed the point of view of the photographer into every image that he or she makes—they can provide vital insight into the look and feel of an era as experienced by a particular person at a particular time.

To get a general view of this period, I looked at photographs made between 1914 and 1918 in the Photography Collection of George Eastman House, the world’s oldest museum devoted to photography. I was only able to view a fraction of those made during the war years, but I found some incredible photographs, shown here.

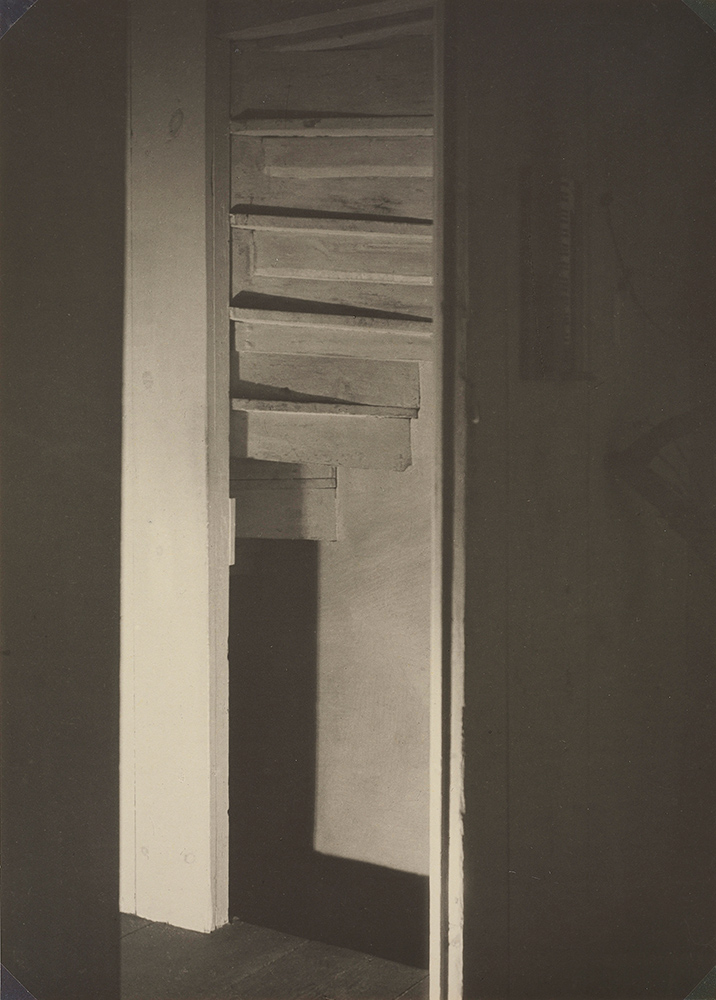

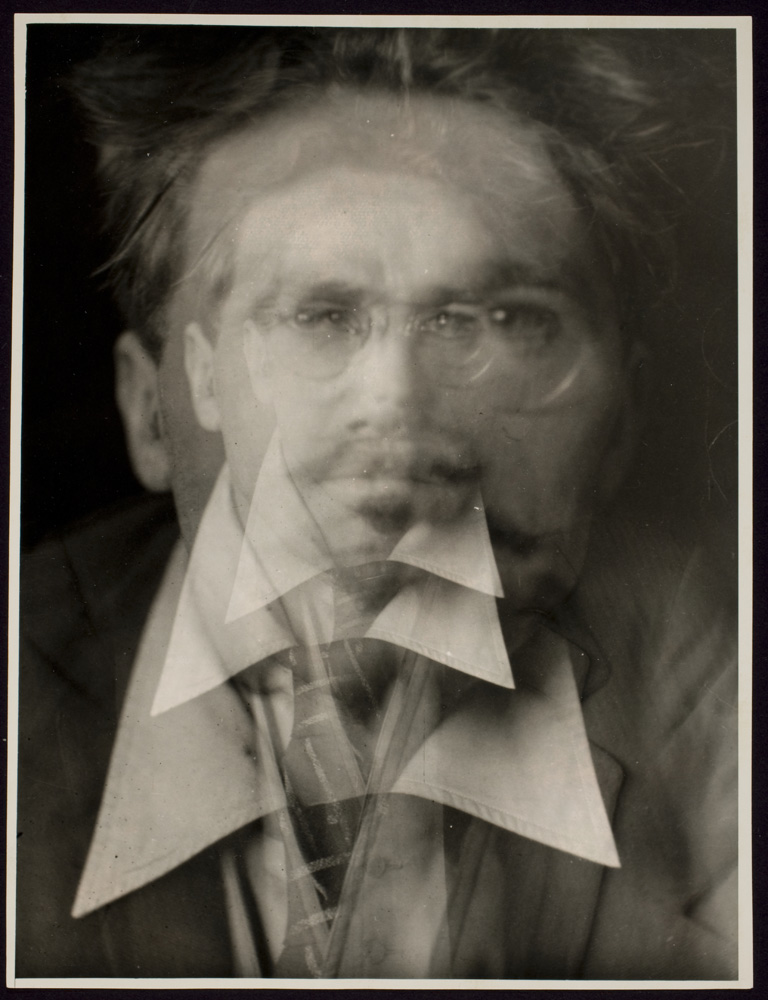

In the process, I was reminded of simultaneities that are easy to forget when one is looking at photography from only one perspective, as either historical record-making, as creative expression or as rhetorical explication. Often, a photograph performs all of these functions at once, regardless of the photographer’s intent. For example, Alvin Langdon Coburn’s portrait of Ezra Pound is one from a series of “vortographs” that he made in 1917. At that time, Coburn was living in England and actively involved in the circle of painters and poets associated with Vorticism, a movement that celebrated the dynamism of modern life and challenged cultural conventions. The abstract paintings of Wyndham Lewis and elliptical poetry of Pound are key Vorticist hallmarks, but Coburn’s photograph seems to channel the chaos and confusion of 1917 as a centrifugal force that threatens to shatter personal identity from within, like shrapnel in flesh.

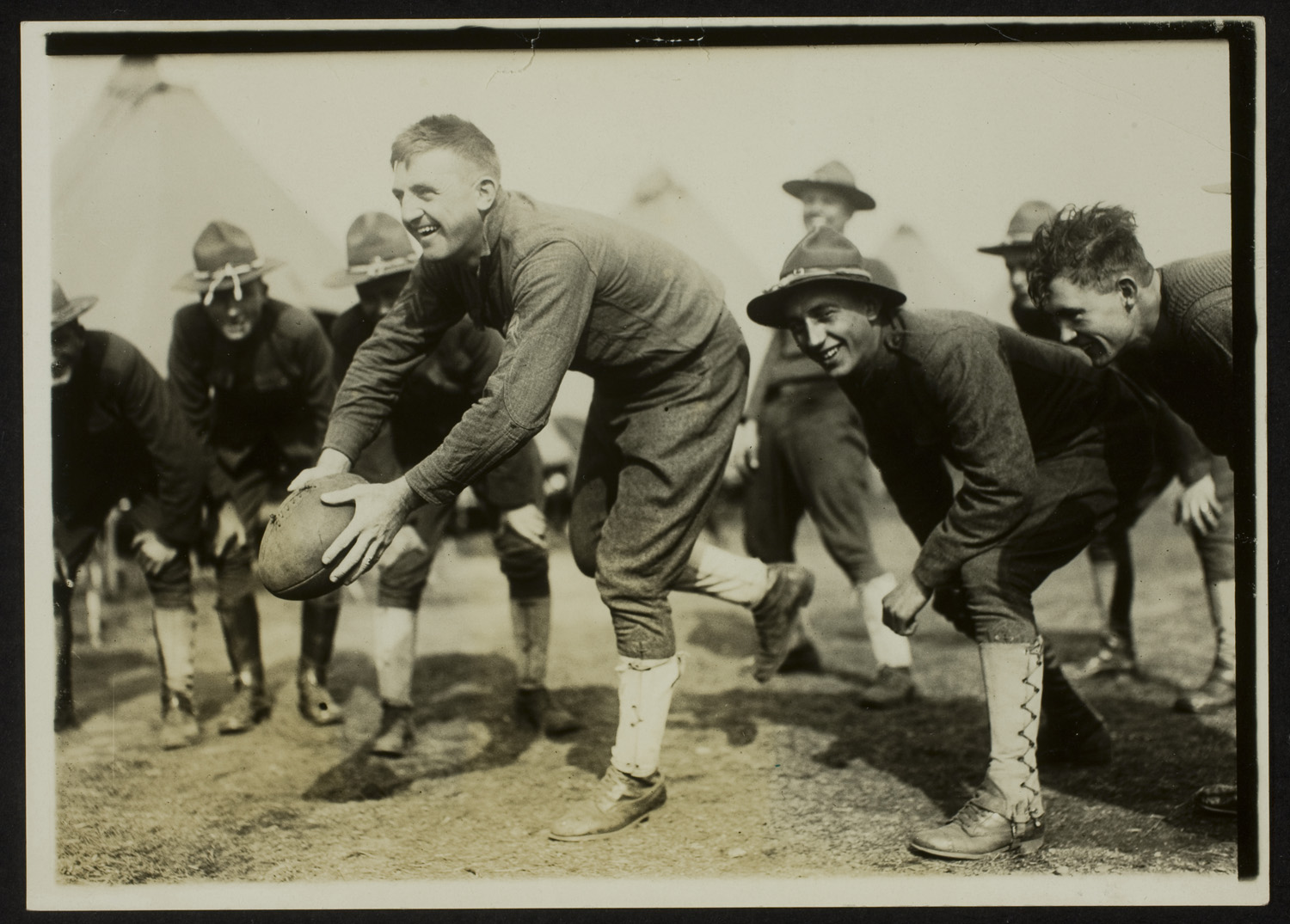

The snapshot of Nickolas Muray (who became a successful color photographer in the 1920s) reminds us that in 1914, upper middle class families like his had no idea of the changes World War I would bring; similarly, Lewis Hine’s photograph of soldiers playing football on the eve of their deployment leaves little indication of the devastating experience awaiting them.

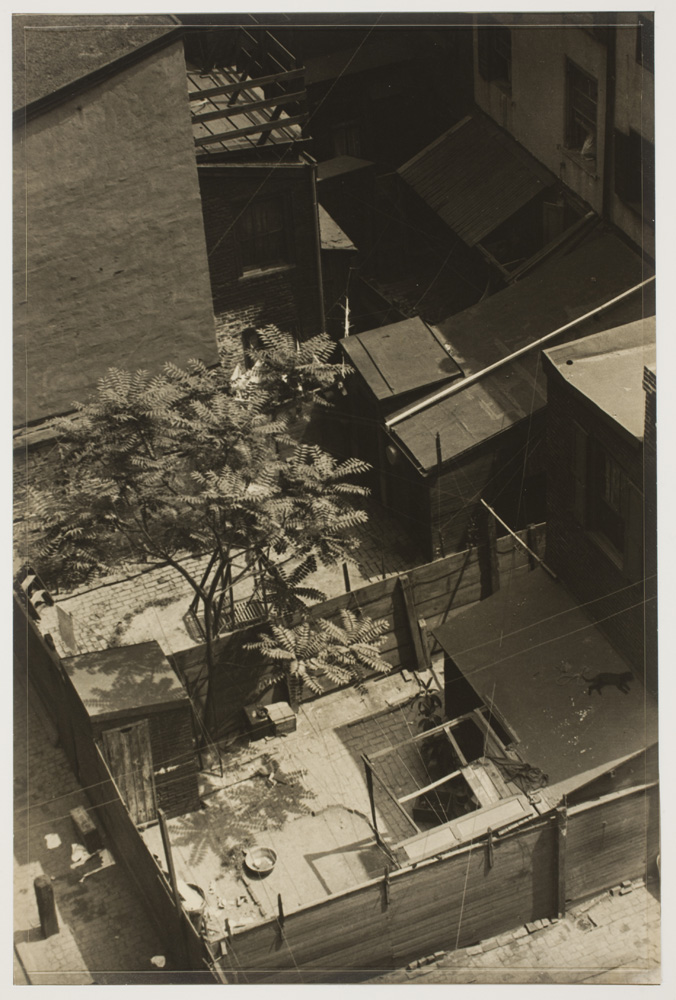

Aerial photography was a brand new enterprise in 1914, as the photographs of men learning to make and interpret aerial photographs illustrate. During these years, Edward Steichen and Alfred Stieglitz shifted their style from Pictorialism to Modernism as they continued to advocate for photography as a fine art; Morton Schamberg, whose great artistic potential would never be realized, died at age 37 in the influenza epidemic of 1918; and Elias Goldensky and Harry Lerner used experimental color photographic processes with very different results.

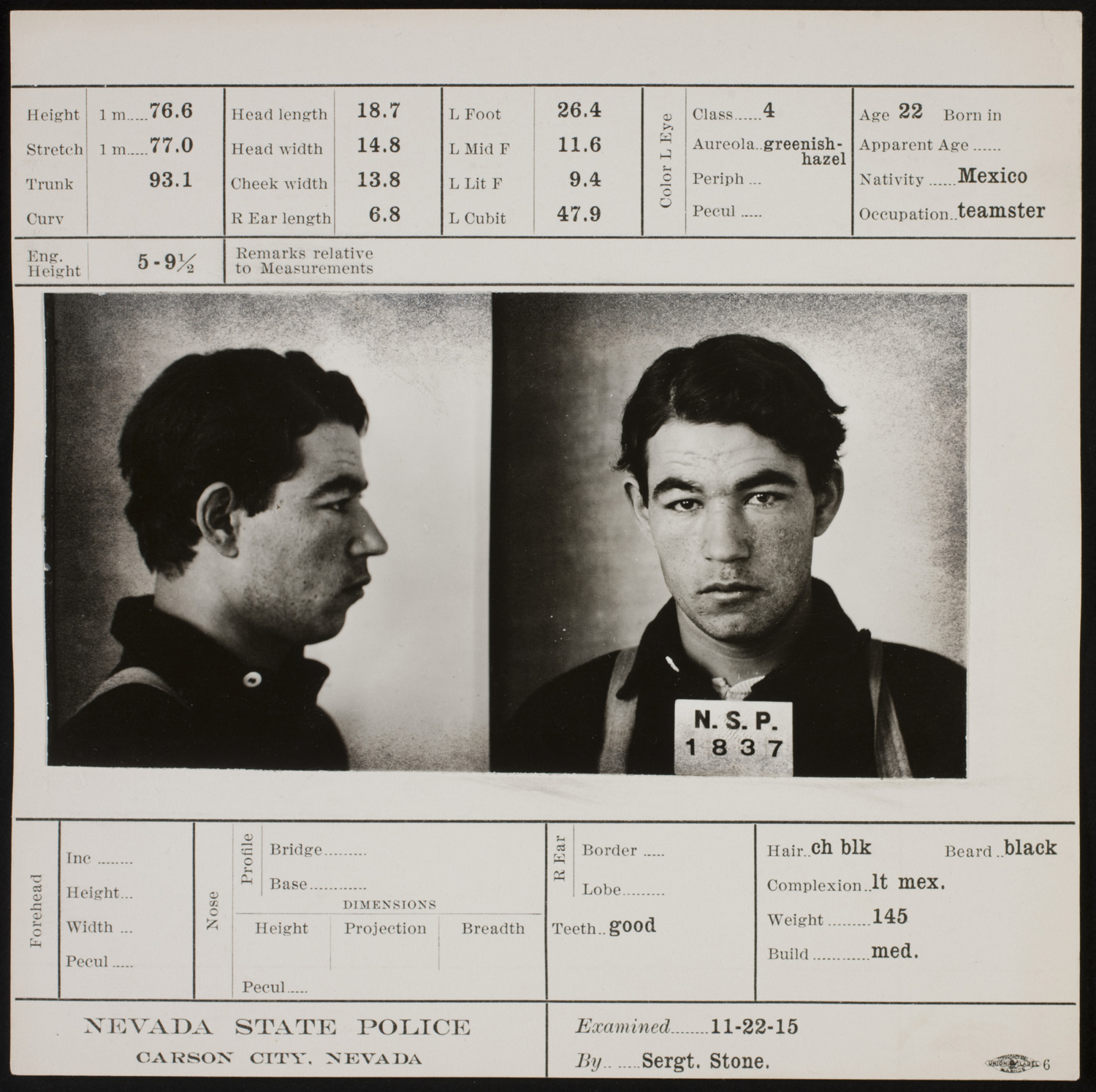

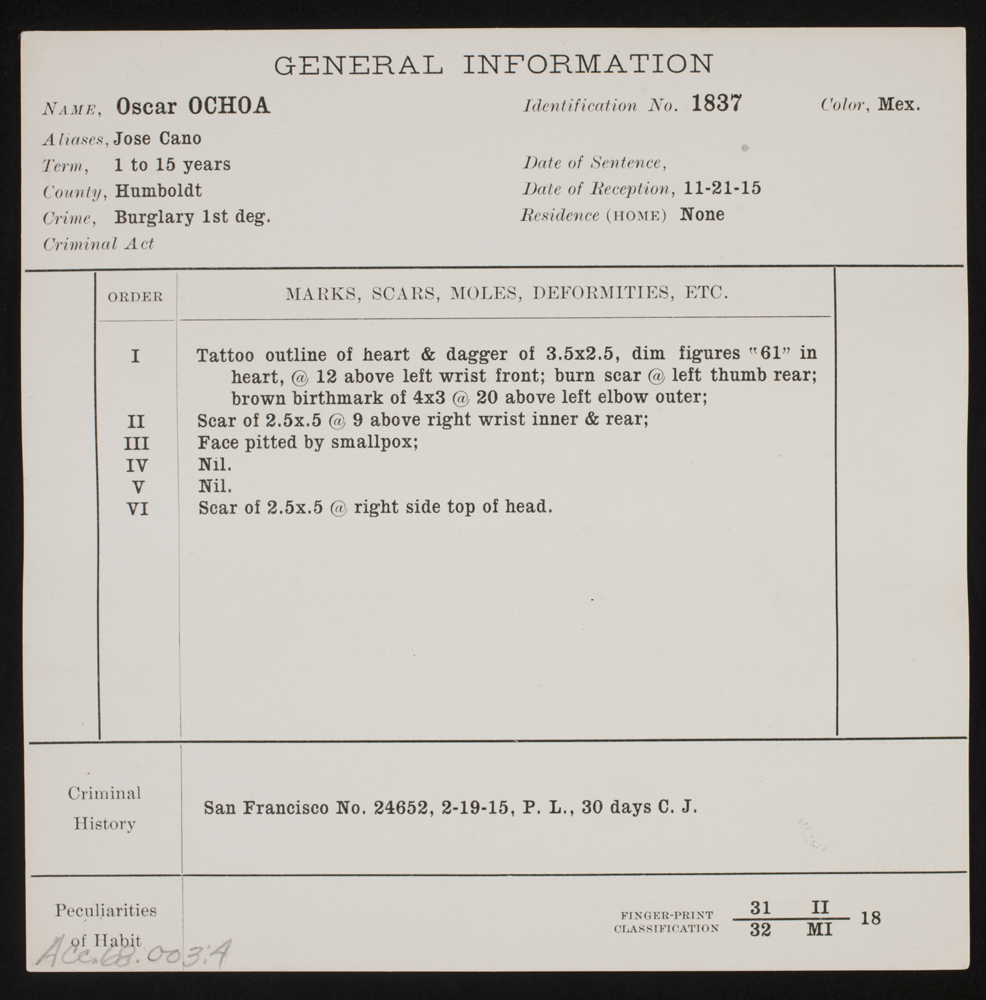

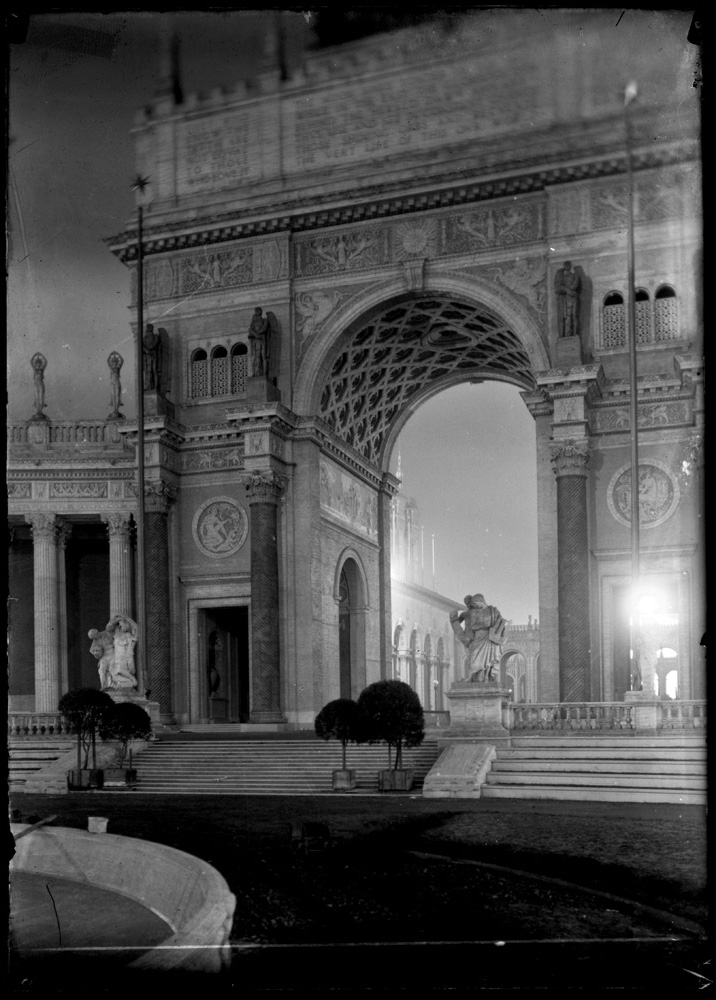

All the while, criminals still committed crimes, as the mug shot of Oscar Ochoa confirms, and ambitious businessmen still sought to expand their reach with extravagant productions like the Pan-American Exposition of 1915, photographed by Francis Bruguière.

Looking at this cross-section of images made me realize how diverse life is at every moment in history and how global events such as World War I permeate all aspects of society.

Lisa Hostetler is Curator in Charge at the Department of Photography at George Eastman House in Rochester, New York.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- TIME’s Top 10 Photos of 2024

- Why Gen Z Is Drinking Less

- The Best Movies About Cooking

- Why Is Anxiety Worse at Night?

- A Head-to-Toe Guide to Treating Dry Skin

- Why Street Cats Are Taking Over Urban Neighborhoods

- Column: Jimmy Carter’s Global Legacy Was Moral Clarity

Contact us at letters@time.com