The Netherlands-based photo collective, NOOR, recently welcomed two photographers — Sebastian Liste and Asim Rafiqui — to its roster, signaling a desire to add fresh coverage on a range of under-reported local issues, from South America to Pakistan, India and across Africa.

The two new associate members join NOOR’s 10 current photographers: Nina Berman, Pep Bonet, Andrea Bruce, Alixandra Fazzina, Stanley Greene, Yuri Kozyrev, Benedicte Kurzen, Kadir van Lohuizen, Jon Lowenstein and Francesco Zizola.

Liste, a Spanish photographer and recent TIME contributor who divides his time between his home country and Brazil, joins from the Reportage by Getty Images agency, where he spent the last three years. But Liste’s relationship with NOOR (a word that means “light” in Arabic) started four years ago when he first met Pep Bonet, one of the agency’s founding members. “I had just started working on my Urban Quilombo project and he was very passionate about it. He helped a lot with edits and he advised me.” The following year, he met another NOOR member – Francesco Zizola – who, he says, also took a particular interest in the work.

“Every year, they’d tell me they wanted me at NOOR, but I didn’t feel ready,” the 29-year-old explains. “I didn’t have the experience, and I didn’t feel I could add something to the agency. I needed a period of time to understand what’s going on in the industry, how it’s changing.”

Last month, NOOR tried again. “They wrote me these amazing letters, asking me to join. And I just thought: ‘Why not? Maybe now is the right time.’”

For Liste, joining NOOR is about finding a structure where he can develop his life-long projects. “The most important thing for me is not how to make money but, instead, how to approach long-term projects,” Liste tells TIME. “I wanted to work with a small community of photographers. I needed a place that trusted my work and did something about it. NOOR is a place where you can put all of your energy and be part of a group where you can grow your ideas. I can’t think of many collectives and agencies that can do that.”

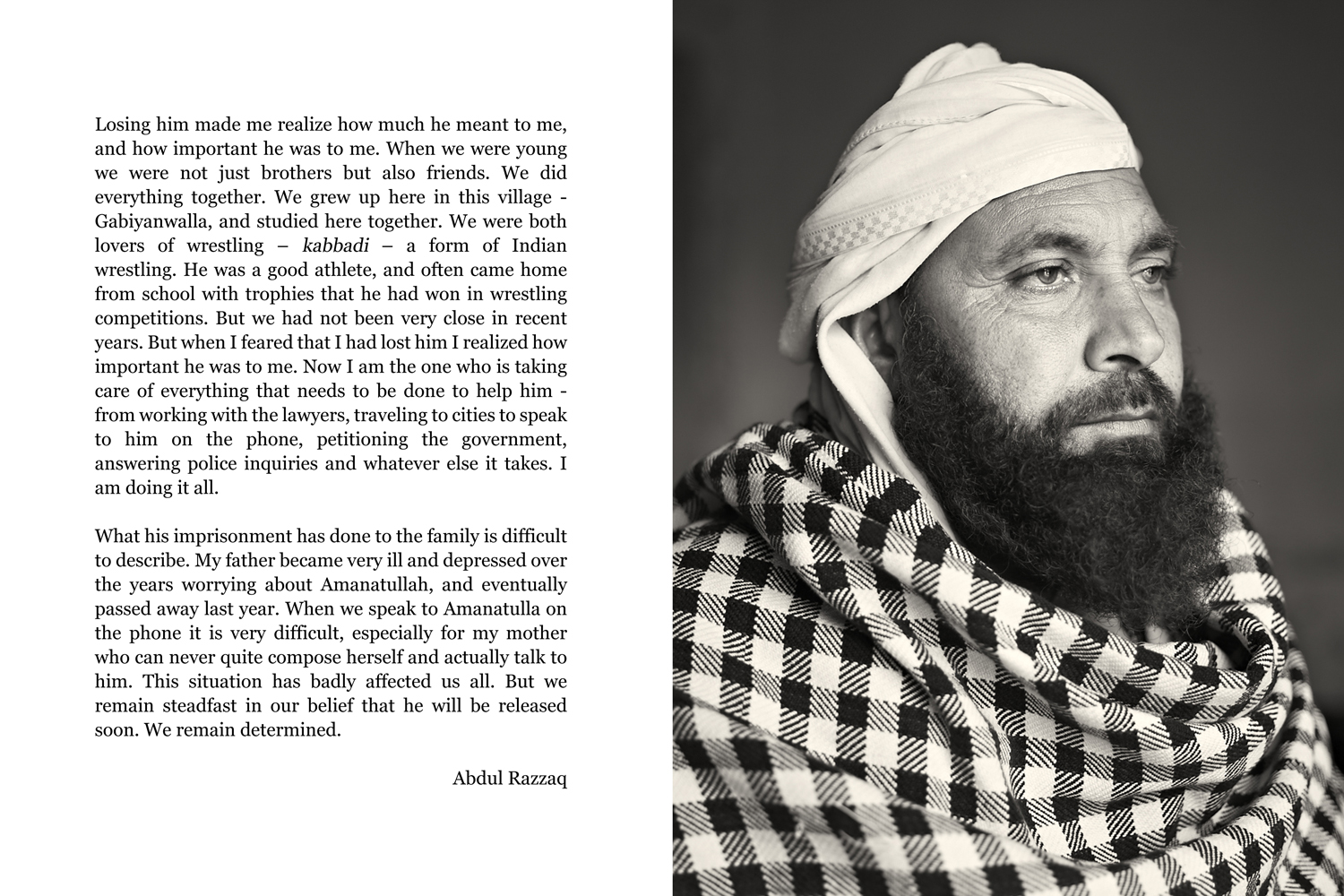

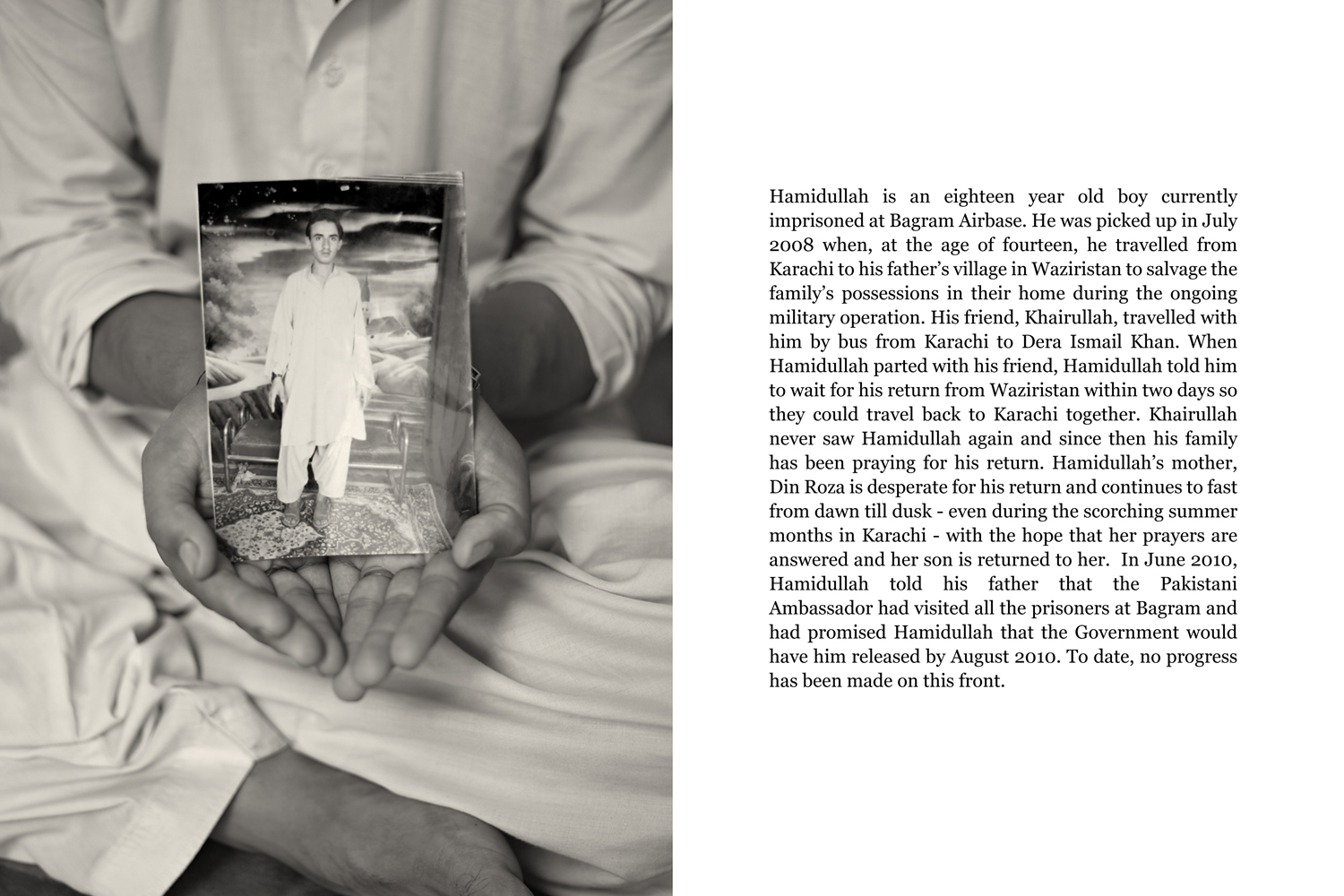

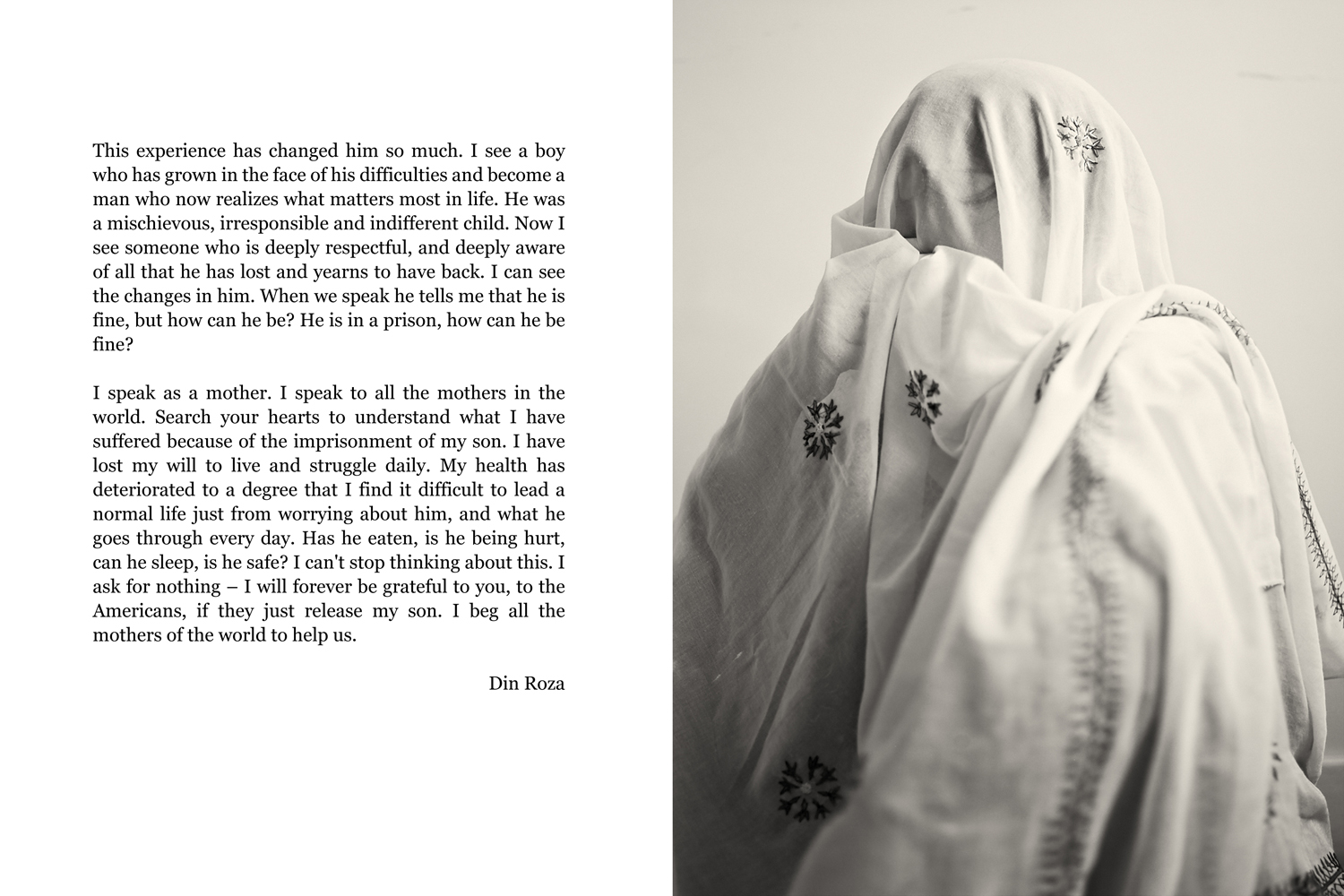

While Liste’s approach to photography is similar to many of NOOR’s members, Asim Rafiqui’s isn’t. For the past eight years, the 48-year-old Pakistani photographer has worked on the fringes of traditional photojournalism.

“I’ve been pursuing very personal projects,” he tells TIME. “I’ve worked with different publications, but that’s never been my focus. My goal has always been to create complex work.” For example, in The Idea of India, Rafiqui challenged notions that Hindus, Muslims and Christians are “oppositional groups, irreconcilably pitted against one another,” he writes on his website. “India’s actual, lived experiences suggests a long history of religious exchange and accommodation and a resistance to ideologies that impose a uniform, high culture on a society where once nearly all its people lived a vernacular culture.”

For Rafiqui, journalists and photographers have a responsibility to combat these stereotypes, especially when they approach projects in Africa and Asia. “My struggle has been to argue and explain that history is not a series of breaks – [but instead that] history continues,” he says. “We are living through the post-colonial era and we retain many of these colonialist and Orientalist cultures within our own countries.”

For example, on his blog, The Spinning Head, Rafiqui has been particularly critical of Western NGOs, which, he tells TIME, still employ colonialist arguments and philosophies. “In the last decades of colonialism, [when new nations were born] the discourse very much became about saving the natives from their backwardness – that they weren’t ready, that they needed help. It was all about humanitarianism. I think that we don’t understand where a lot of today’s discourses come from and the politics behind them, and I try to speak against the language NGOs use today.”

When photographers work closely with NGOs, Rafiqui explains, they have to take into consideration the historical and political baggage these organisations bring with them. Instead, photographers should allow for the political, social and economic histories of the nations they visit to come to light. “In these countries, there are local actors, but I repeatedly find that these voices, these characters are removed [from photographers’ stories],” he says. “It’s about realizing that you are arriving, living and breathing in complex worlds. It’s about taking the time to get involved in these worlds, instead of simply claiming that you’re going to save them because they can’t save themselves.”

Rafiqui also argues that mainstream photojournalism is European- and American-centric. “It remains the most influential space because what appears at World Press Photo or in TIME influences tens of thousands of photographers across the globe,” which leads, for example, to South Asian photographers repeating — in terms of aesthetics and narrative construction — the same stories they see in the Western media. “There are other voices and perspectives that are missing from the debate,” Rafiqui asserts.

“At NOOR, there are people who already think like that,” Rafiqui adds, “and I think [by selecting me] they are trying to highlight this. But I don’t want to make them speak like me. Instead, I can maybe challenge them with a perspective that they might not be able to get from someone else. I also want to be pushed by a very intelligent group of people who have very different ways of working and very different ideologies.”

Sebastián Liste is a Brazil-based photographer represented by Noor. In September 2012, he received the Getty Images Grant for Editorial Photography and the City of Perpignan Rémi Ochlik Award. LightBox previously published Liste’s work documenting the community living in an abandoned chocolate factory and Brazil’s love for football ahead of the 2014 World Cup. Follow him on Twitter @SebastianListe.

Asim Rafiqui is a Pakistani photographer represented by Noor. He’s currently based in Kigali, Rwanda, and regularly writes on his blog, The Spinning Head.

Noor is an Amsterdam-based collective of photojournalists and documentary photographers.

Olivier Laurent is the editor of TIME LightBox. Follow him on Twitter and Instagram @olivierclaurent.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Why Trump’s Message Worked on Latino Men

- What Trump’s Win Could Mean for Housing

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- Sleep Doctors Share the 1 Tip That’s Changed Their Lives

- Column: Let’s Bring Back Romance

- What It’s Like to Have Long COVID As a Kid

- FX’s Say Nothing Is the Must-Watch Political Thriller of 2024

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com