Every day, celebrities and paparazzi are engaged in an ongoing struggle in cities, nightclubs and other public places around the world. The nature of this struggle is most often defined by celebrities, by those in their employ and by those sympathetic to their perceived plight, all of whom speak in terms of a fight for privacy — the right to be left alone. Justin Bieber lunging at an allegedly insulting photographer; Alec Baldwin chasing down a photographer who got too close to his family; Kanye West attacking a photographer at LAX — the paparazzi in these stories are often seen as hunters, stalkers, bullies, lawbreakers. They endanger their celebrity victims, their families and even bystanders.

But there is another way to examine this conflict: namely, as a struggle for survival — not in a primitive sense for food or shelter, but for control of one’s image. Indeed, one’s identity. Celebrities, including actors, athletes, musicians and reality TV stars, must build their reputations on more than talent. Over the past century, since the beginnings of the studio-controlled movie industry, celebrity livelihood has depended on defining a seemingly authentic self-image, which includes an offscreen life of friends and family, of amazing parties and vacations, of stunning homes and cars. Celebrities craft for themselves a mediated persona — good parent, wholesome boy or girl next door, vixen or bad boy — through which they establish societal influence.

Celebrities enlist staff — agents, publicists, bodyguards, stylists — to project and protect a consistent image to the public, as they themselves appear across media and engage directly with fans through social media. Friendly media outlets allow celebrities to present a painstakingly defined version of themselves, while simultaneously concealing their less desirable or contradictory behaviors, traits and utterances.

Images, after all, are valuable commodities. A well-constructed image of a celebrity as accessible and yet larger-than-life increases ticket sales, television ratings, endorsement opportunities and can even garner influence in cultural and political realms. Celebrities tell us not only what movies to see but also what products to buy and what social causes to support. Their behavior shapes ideas about gender roles and, in a sense, helps define the American Dream. Their image is a form of power that is quite real — even if the image itself is often not real at all.

A well-crafted image must be protected from circumstances that call into question its constructed nature — its artifice. In this light, the paparazzi threaten to shatter the seamless veneer that celebrities work so hard to maintain. The paparazzi, that group of mostly freelance photographers who are despised by celebrities and conventional journalists alike as unethical predators, produce candid, often unflattering pictures and videos that celebrities would obviously prefer to keep hidden. Exposure by the paparazzi is not just embarrassing but can be economically damaging, threatening endorsements or hurting box office sales.

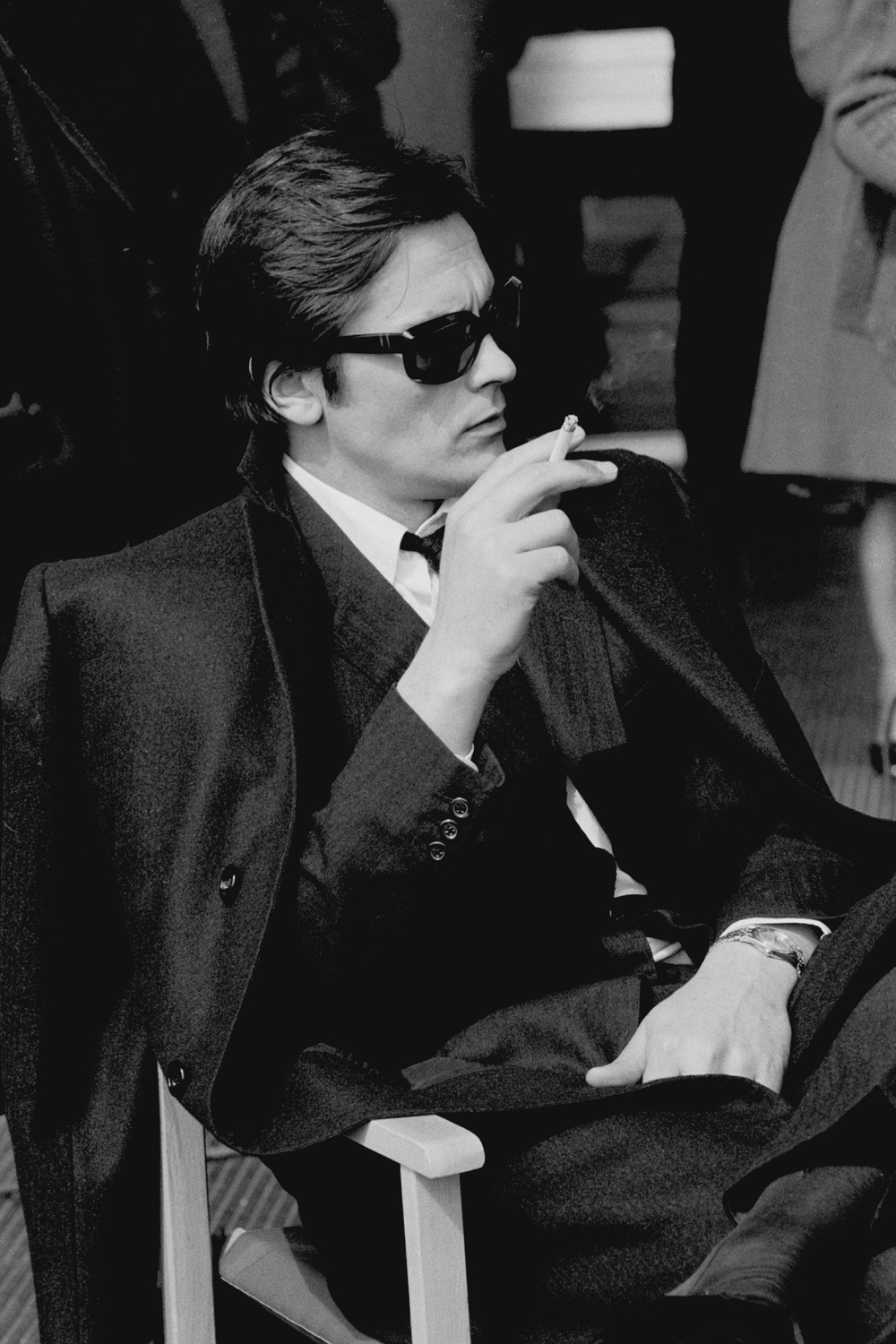

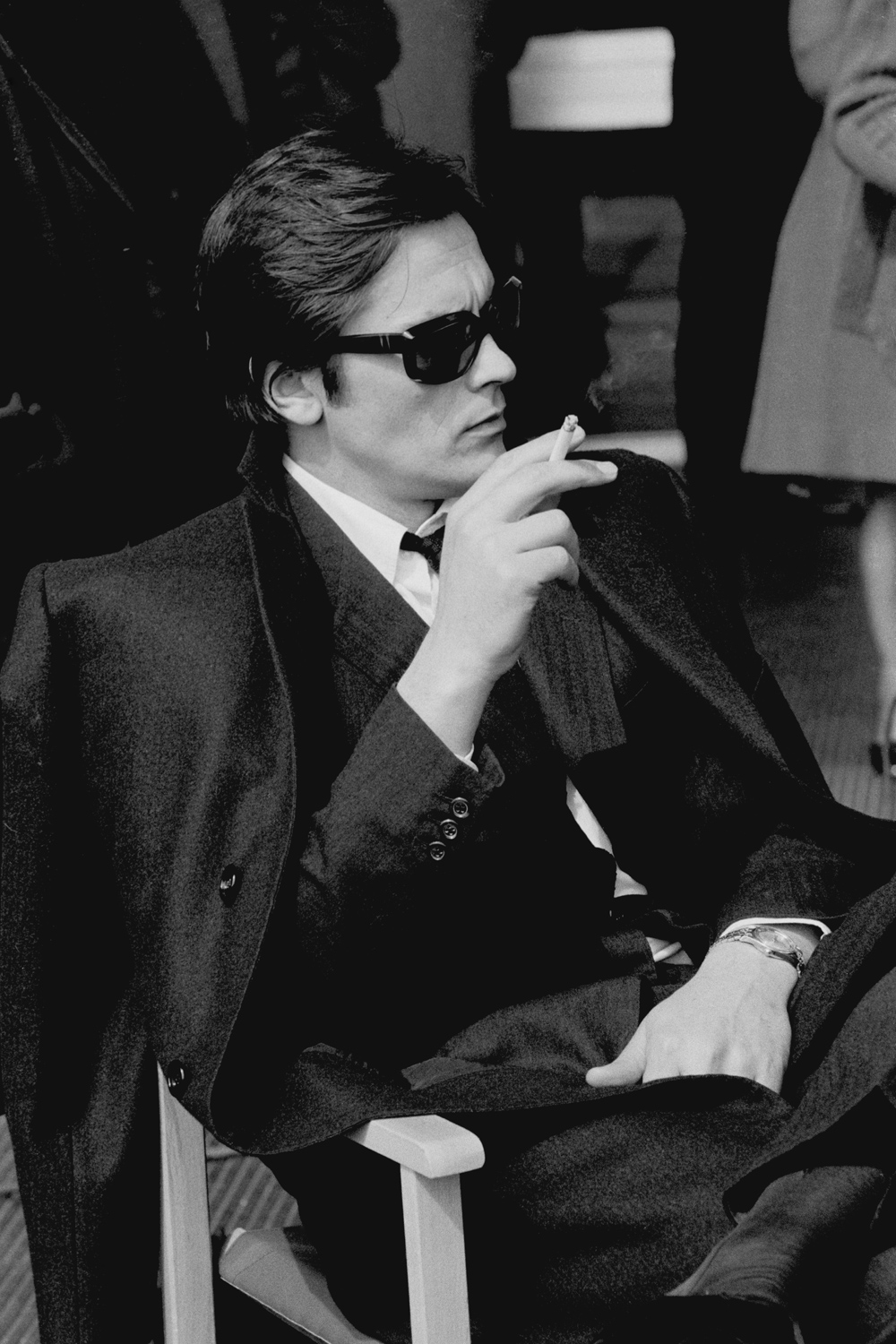

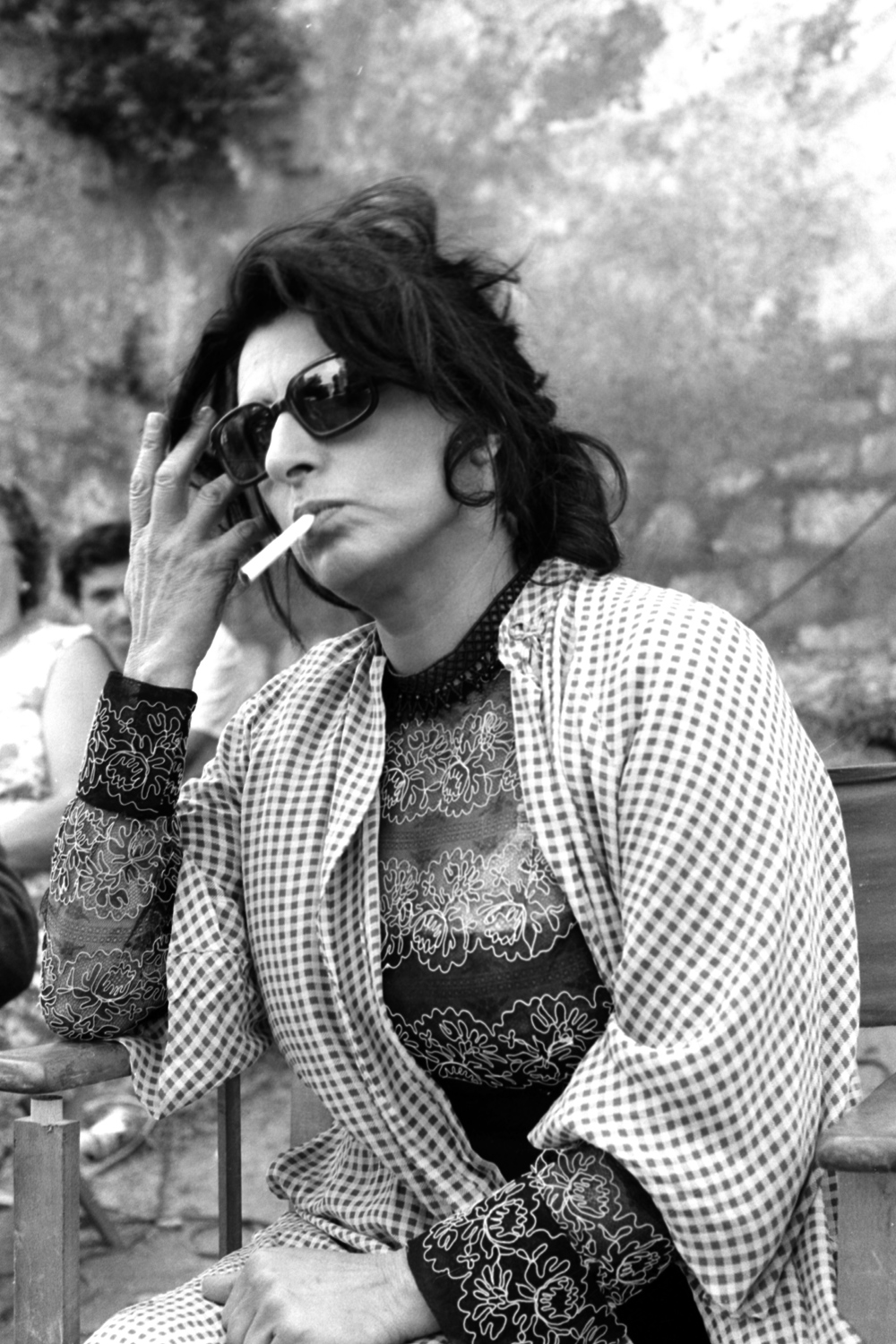

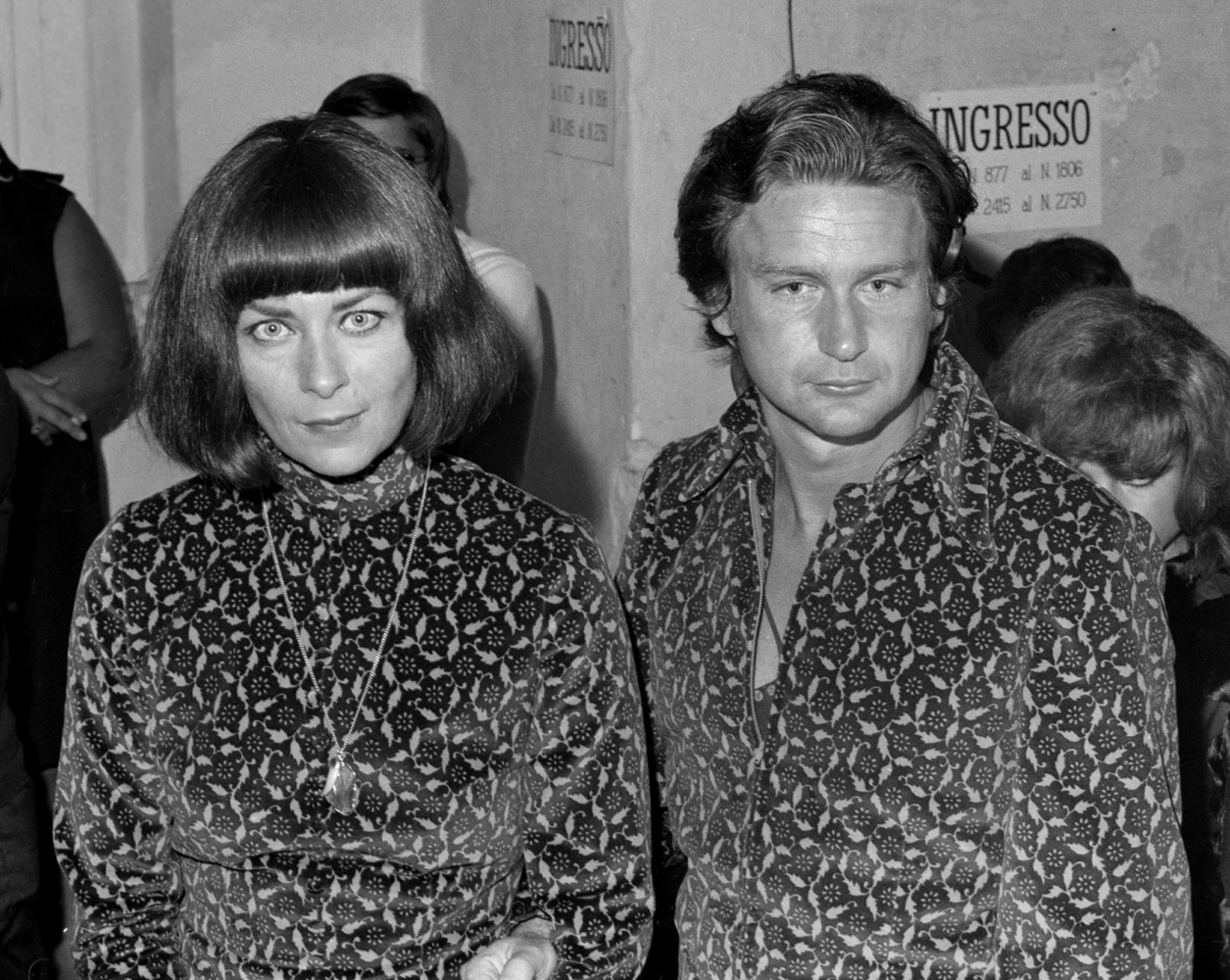

The paparazzi are distinct from photographers who work in situations — posed photo shoots for magazines, red carpets and parties — that allow celebrities control over how they appear. The paparazzi’s quest for raw, candid photos places them, as photography scholar Carol Squires argues, “outside the bounds of polite photography.” There is an anti-aesthetic to paparazzi photographs that rejects the “official,” glamorous views of the rich and famous. The best paparazzi photographs emphasize fleeting, stolen moments, ideally produced without the subject knowing he or she is being photographed.

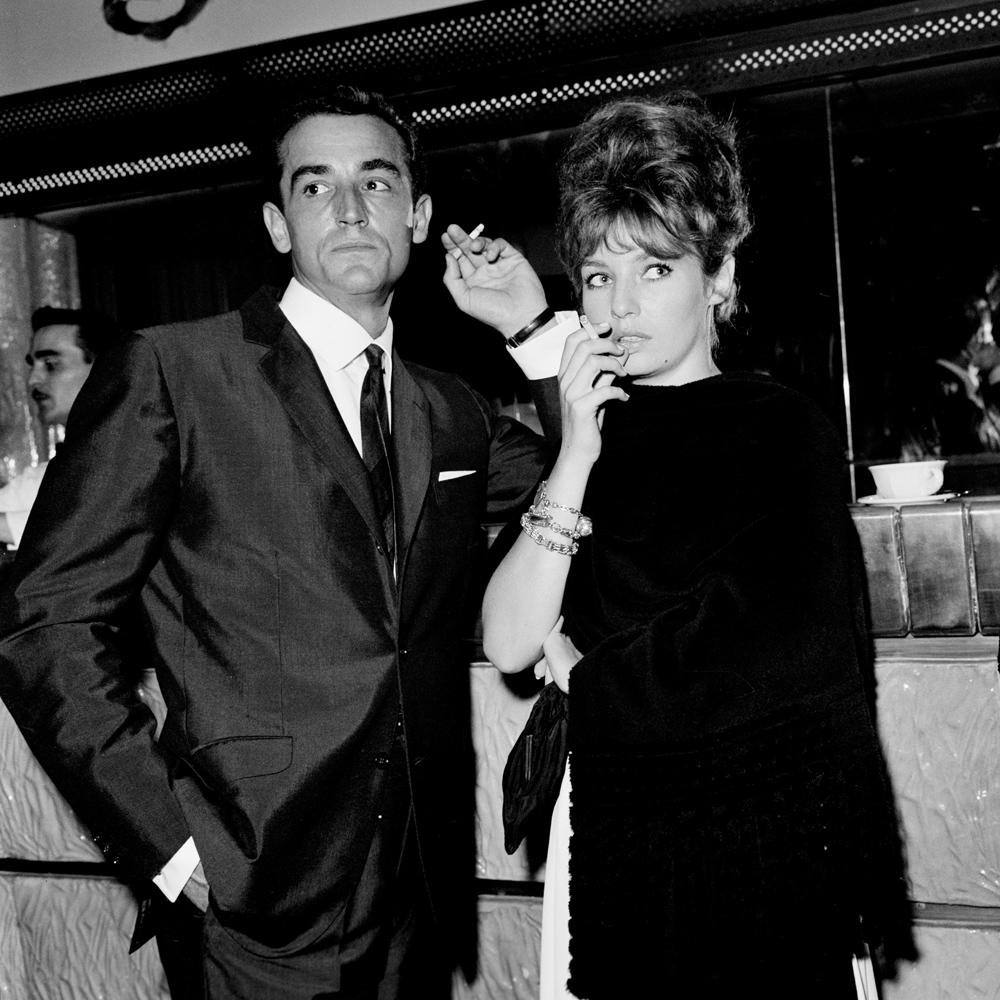

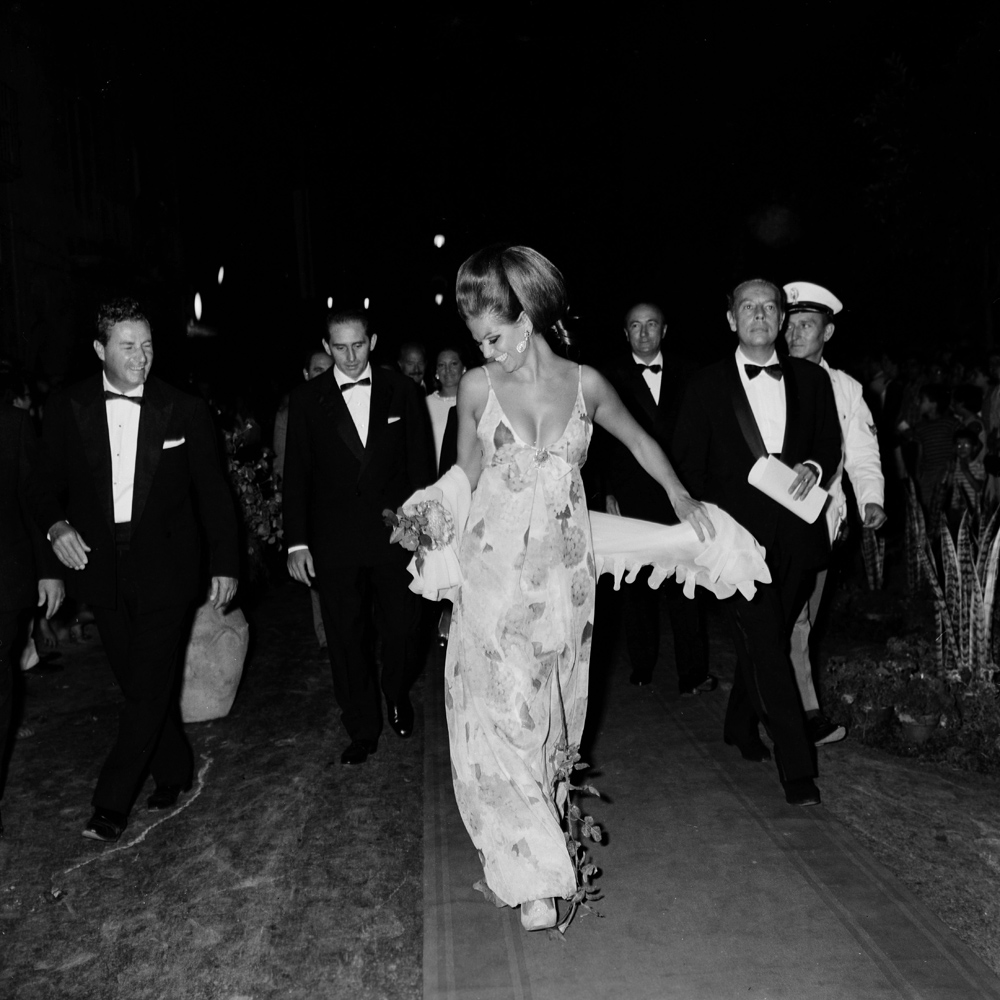

Paparazzi are direct descendants of celebrity gossip columnists of the 1920s, ’30s and ’40s, including Walter Winchell, Hedda Hopper and Louella Parsons, who regaled audiences with juicy (if highly selective) tidbits about the personal foibles and scandals of the stars, often contradicting the studio-sanctioned versions of the stars’ lives. The first paparazzi emerged in post-war 1950s Italy, where for financial reasons a number of U.S. movie companies had relocated their productions. Rome came alive each night, after the day’s filming was over, as a playground for actors, actresses, directors, former and current royalty and other world elite frequenting the cafes, clubs and restaurants along Via Veneto and other chic streets. Photographer Elio Sorci, for example — whose work is explored in depth in a slideshow above — patiently stalked the streets of Rome looking for unguarded moments of these stars. Once, in March 1962, he hid out all day under a car to get a photograph of Richard Burton kissing Elizabeth Taylor outside the Italian movie studio Cinecitta, exposing their relationship to the world. One of his most notorious sets of photographs was taken one night in 1958 when fellow photographer Tazio Secchiaroli was set upon by Italian actor Walter Chiari, outraged at Secchiaroli firing off his flash gun directly in the face of actress Ava Gardner. Sorci along with Tazio Secchiaroli, Felice Quinto, Rino Barillari and others, visually defined the energy of these times.

The very word paparazzi derives from Federico Fellini’s 1960 film La Dolce Vita and the frenetic photographer Paparazzo, played by Walter Santesso, seen running to photograph Anita Ekberg’s character ahead of other photographers. These photographers produced pictures that stood in stark contrast to the glamorous and controlled photographs distributed by the movie studios or the staged images in popular magazines like LIFE and The Saturday Evening Post. Audiences devoured pictures of Frank Sinatra, Peter O’Toole, Ava Gardner, David Niven, Shirley MacLaine and Audrey Hepburn and others. They relished the soap-opera quality of seeing Elizabeth Taylor kissing Richard Burton on a yacht, when both were married to other people.

Today, this same desire to see behind the glitz and glamor of a celebrity’s image drives audiences with equal fervor to outlets like TMZ. While it is certainly true that paparazzi are doing what they do for money, that doesn’t diminish the important functions their photographs play. More than an invasion of privacy, the paparazzi represent a challenge to the control of a celebrity’s image, and thus to their wealth, status and power. At a minimum, paparazzi photographs poke fun at the cultural elite, allowing audiences to revel in their all-too-human flaws. More significantly, seeing a celebrity in the arms of someone other than a spouse, or seeing a “wholesome” teen star drunk or stoned, calls into question the nature of Hollywood’s star-making machine. These pictures challenge us to question the true motives of those wielding outsized cultural influence and force us to examine the standards we ask our role models to meet.

Occasionally distasteful, that kind of scrutiny is nevertheless a time-honored and, arguably, an essential part of our moral and ethical development as a society.

Andrew L. Mendelson, Ph. D. is the chair of Temple University’s Department of Journalism.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com