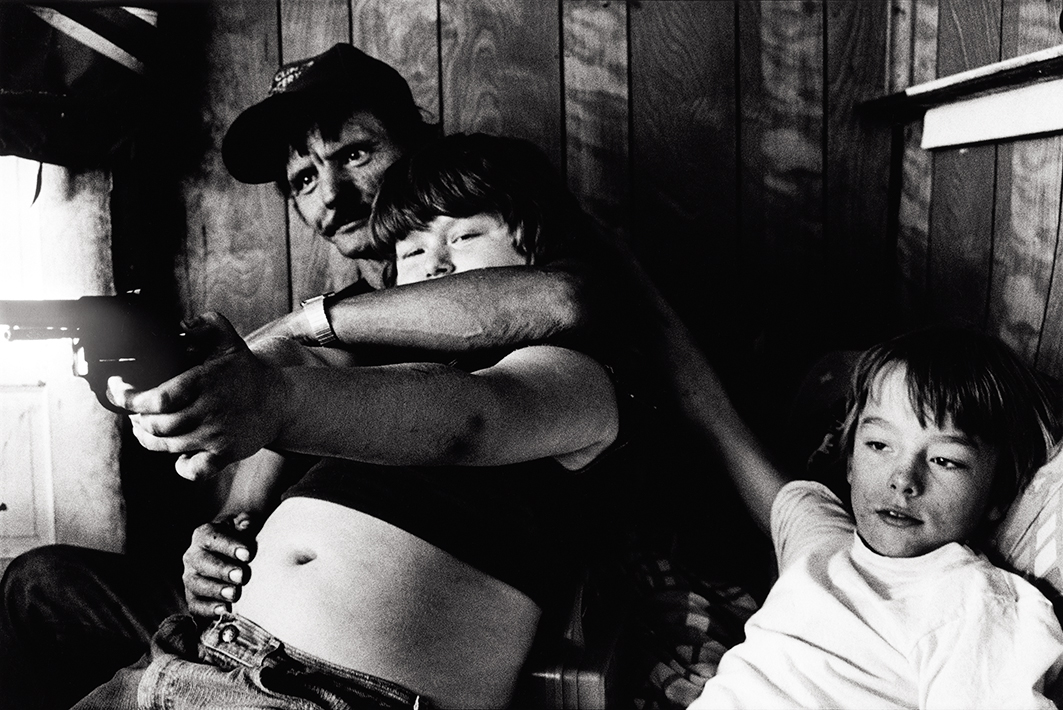

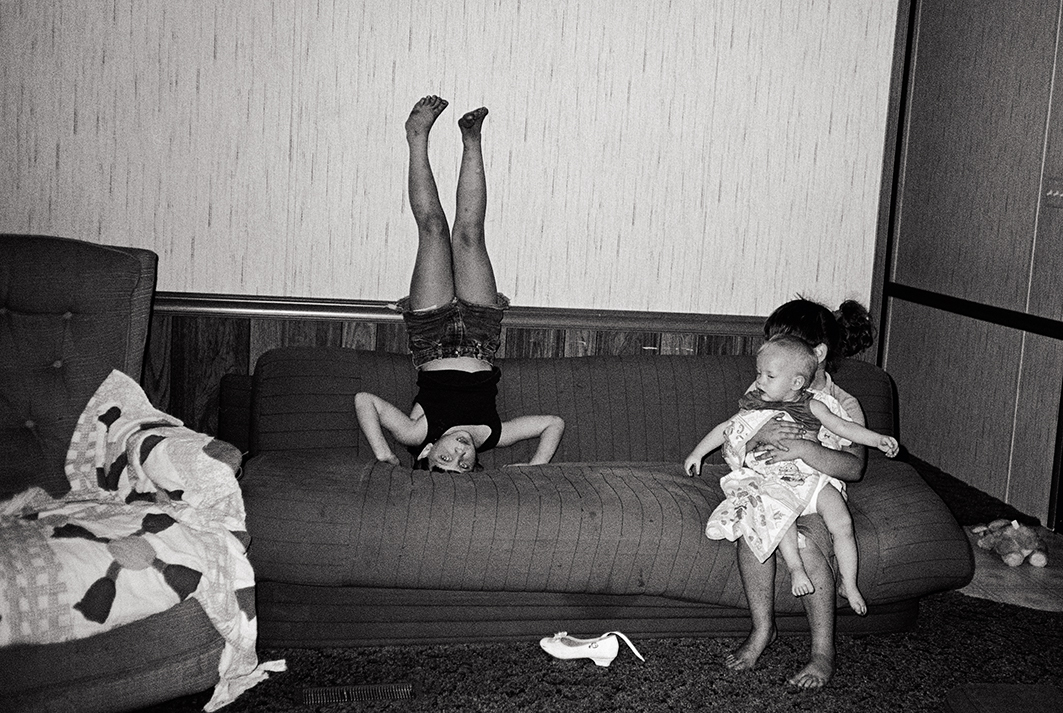

Photography and cinema have not always treated the communities in American Appalachia kindly. Even when approached with the best intentions, the portrayal of Appalachia is often dominated by the region’s poverty and at worst, has centered mainly on the exaggerations of inbreeding, religious practices like snake handling, or other sensational subjects rife with assumptions and easy categorization. No need to try to understand these communities as human beings with hopes and dreams and frustrations like others – in the shorthand language of pictures they are often simplified into shotgun-toting, ‘hillbillies’. The exception is what I find in Bertien van Manen’s newest book Moonshine from MACK.

Van Manen was raised in a mining area in the south of the Netherlands and has had a long fascination with miners and mining communities. When in 1985, a professor in Leeds, UK told van Manen about women working in mines in Appalachia, she traveled to the US to photograph them, with the help of woman named Betty Jean Hall, who was working as a lawyer to several Appalachian families.

Known as communities that, understandably enough, are suspicious of outsiders, van Manen worked hard to establish a sense of trust. She stayed for months at a time, living with families and shooting with small cameras. “Sometimes I just went up a holler without knowing anyone, with a pounding heart; it always went well. After suspicion and holding back, people appeared to be intrigued and became hospitable. I always stayed with them in their trailer or house, never in a hotel. Living their life and not using large cameras, I was not considered as threatening. After a while, people liked their pictures to be taken.”

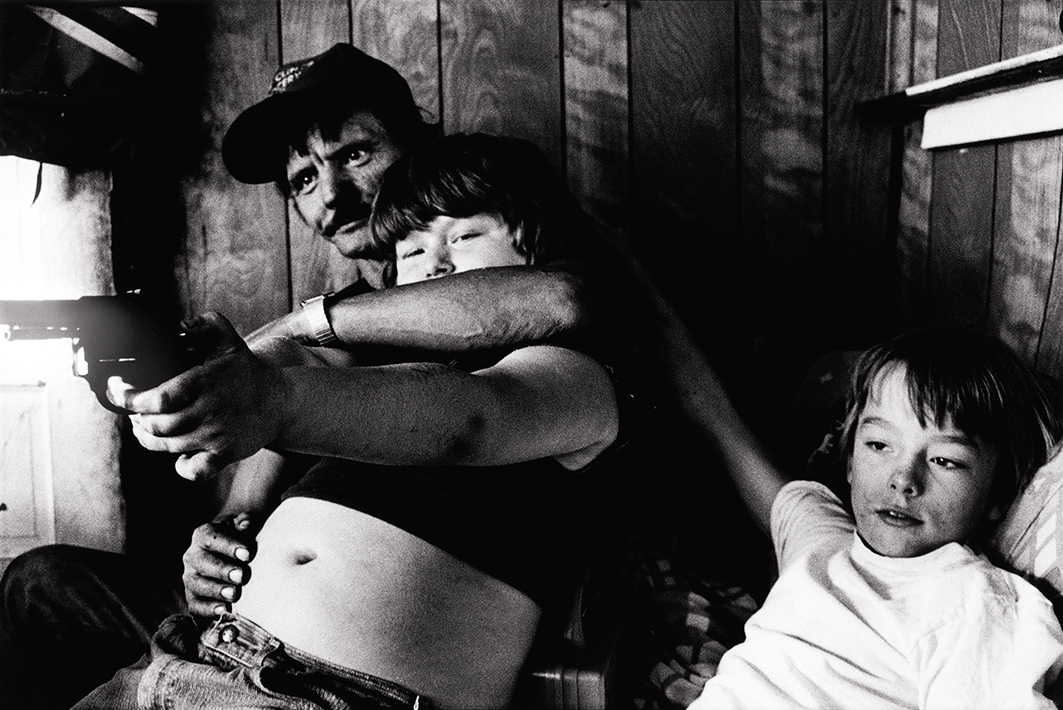

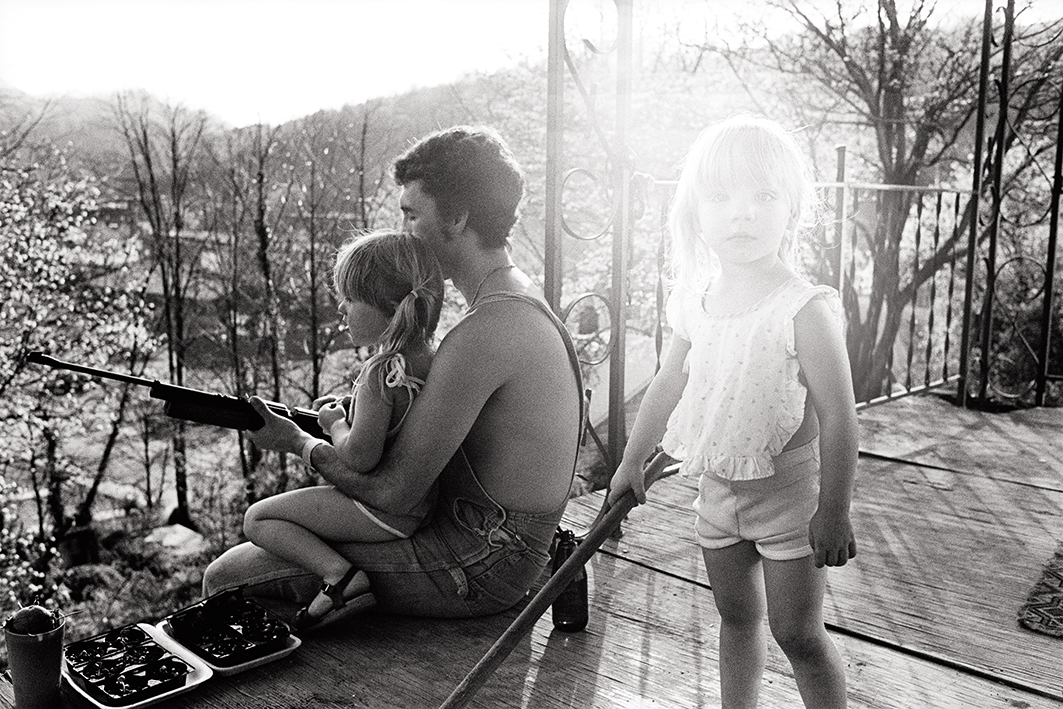

Although the region’s poverty can certainly be felt in van Manen’s photographs, it plays a very minor role. Instead we trespass on moments of intimacy and beauty unmarred by artistic pretension. In one, five men stand in conversation over beers but each displaying their own unique body language; in another a young woman combs the hair of an older – the curves of hair mimic the falls of the younger woman’s dress; in others, children seem to be defying gravity with their handstands and play flips.

Spanning almost 30 years, van Manen’s collection amounts to an intergenerational family album of sorts mixing van Manen’s early black-and-white and later color images freely. In putting together a sequence for the book, says van Manen, “the idea came along of creating rhythm by alternating spreads with one or two pictures, always combining a black-and-white with a color photo. It was interesting to see that you could play a kind of memory game: to create a relation between photographs that, in time, were far apart. For example you could sometimes make believe that a black-and-white picture copied elements of a colour photo that was actually taken years later.”

Brief vignettes written by van Manen in 2013 act as an introduction to the book and recall experiences while living in Appalachia. One from 1987 reads; For four months I make my home in a tiny camper next to the trailer where Mavis and Junior live. They sleep on the floor, behind the sofa. Mavis’s son Cris stays in the bedroom. In a wooden house next door lives Junior’s son Billy, just back from three months behind bars, with his wife Sue and the children Justin, Chet, Megin, Amanda, the baby Jennifer and later on young David. I spend a lot of time at their house and take pictures of the children playing, both indoors and out. When the baby Jennifer dies suddenly, the photograph I have made of her is the only one Sue has. At night on the porch we see the lights of the town twinkling down below, and we listen to the heartrending ‘hoowee’ of the coal trains rolling straight across town.

The title Moonshine can initially seem to bring back those stereotypes of hillbillies but it also serves, for me at least, a deeper metaphor referring to moon-shine as quality of light. Van Manen’s point and shoot style of photography is one of allowing imperfections in technique stand. In many of her images there is often an unearthly quality to the light; for instance the unnatural glow of the girls’ back in the book’s cover image as she runs from the camera; in an early black-and-white image of four children sitting on a sofa, the two girls in the center dissolve in the glow of the window light; fiery light leaks stain an image of a man in a coffin at a funeral.

It is said that in the distilling of ‘moonshine’ whisky, the clearer the liquid looks the more powerful the alcohol. In Bertien van Manen’s Moonshine the opposite may be true, imperfection handled with a fierce respect and admiration has allowed for a stronger more powerful drink that few have been able to produce.

Bertein van Manen is a photographer based in the Netherlands. Her book, Moonshine, is out now.

Jeffrey Ladd is a photographer, writer, editor and founder of Errata Editions.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Donald Trump Is TIME's 2024 Person of the Year

- Why We Chose Trump as Person of the Year

- Is Intermittent Fasting Good or Bad for You?

- The 100 Must-Read Books of 2024

- The 20 Best Christmas TV Episodes

- Column: If Optimism Feels Ridiculous Now, Try Hope

- The Future of Climate Action Is Trade Policy

- Merle Bombardieri Is Helping People Make the Baby Decision

Contact us at letters@time.com