Bedrooms are places of repose and rejuvenation. The Beach Boys sang of such special sanctuaries long ago, as the Vietnam War began: “There’s a world where I can go, and tell my secrets to, in my room, in my room,” they crooned. “In this world I lock out all my worries and my fears…”

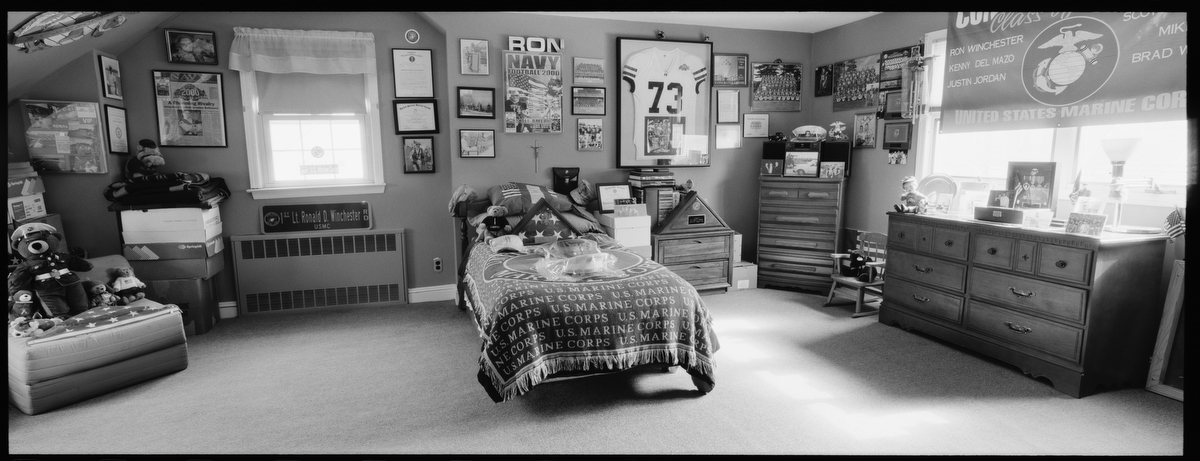

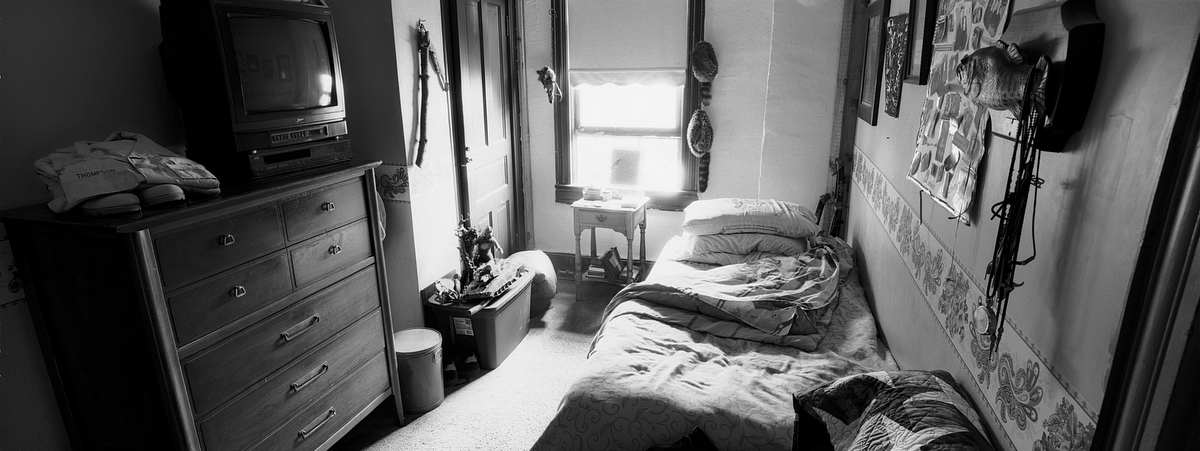

Why can’t they also be places of remembrance? That’s the idea behind a starkly beautiful new book, Bedrooms of the Fallen, by photographer Ashley Gilbertson. The volume consists of still-life photographs of 40 bedrooms, where troops from the U.S. and around the world slept before dying in the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq, or their aftermath. It’s to be published by the University of Chicago Press this June.

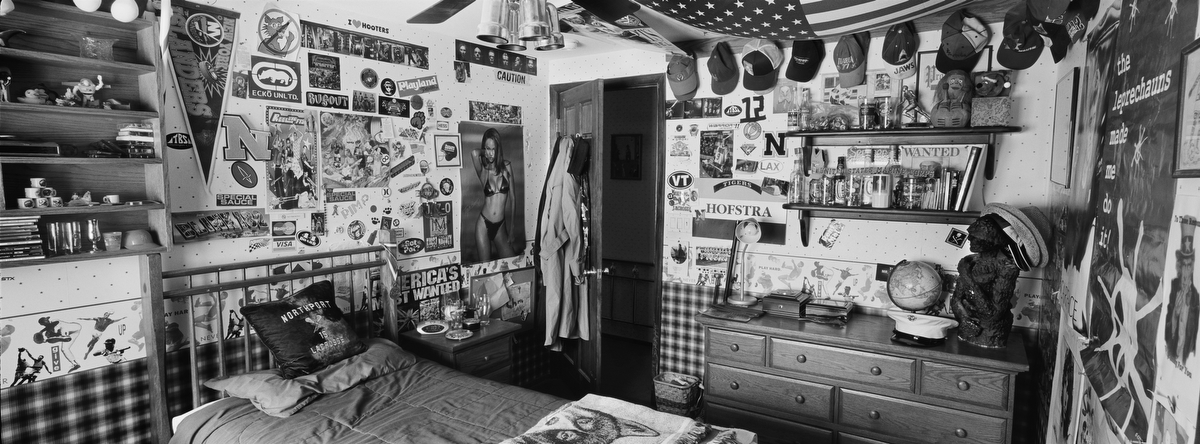

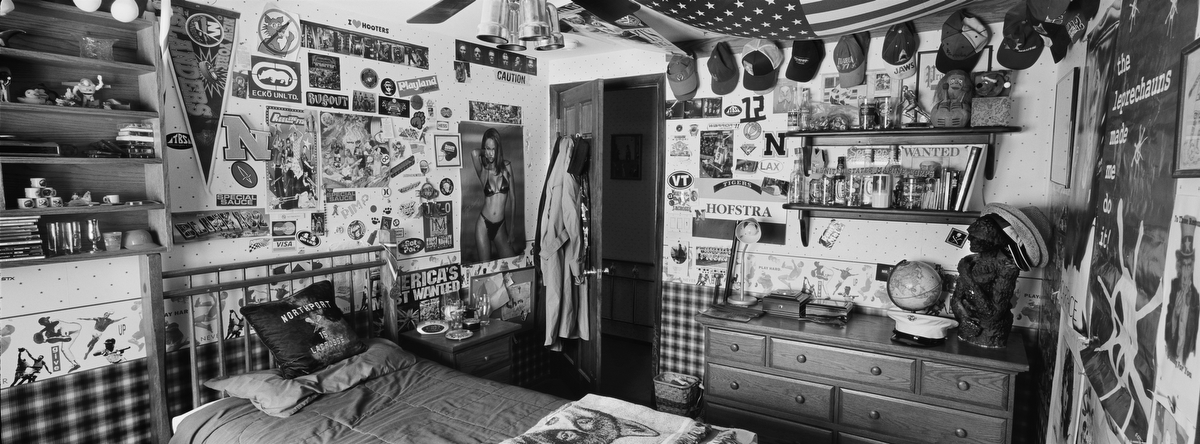

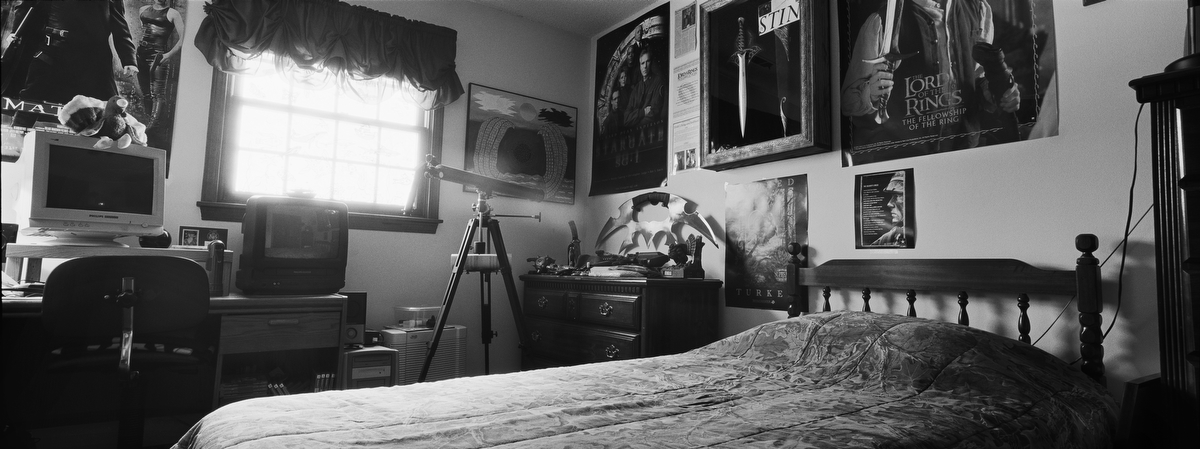

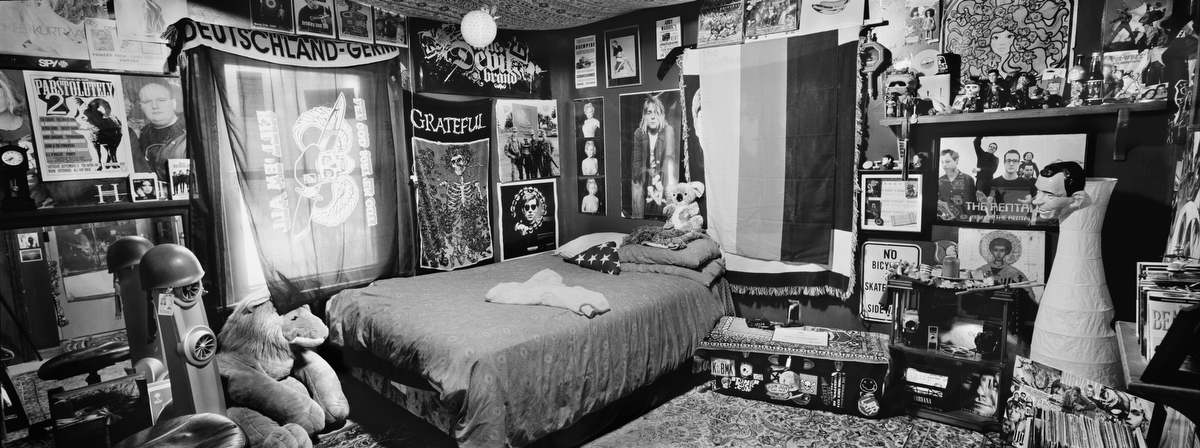

“When we lived with our parents, most of us had one room to ourselves. Our bedroom was the space we took ownership of, and in it we placed the things we loved most, reminders of what we longed for and aspired to,” Gilberston writes. “It was a place to which we could retreat from the world and feel protected. There we could express ourselves without judgment, and only our mothers could make us clean it.”

Gilbertson spent seven years on the book, including six in Iraq. He dedicates it to Marine Lance Corporal Billy Miller, who accompanied him up a minaret in Fallujah in 2004, to photograph a slain militant who had been using the mosque’s highest point as a sniper’s nest. “Moments before we reached the top, Miller was shot pointblank by an enemy fighter. I ran out as fast as I could, covered in Miller’s blood, forever changed,” Gilberston says. “I came home…Billy Miller didn’t. I needed to photograph his absence.”

He decided to honor some of those who never made it back by visiting their empty rooms, preserved, usually, by parents. You get a sense, gazing at the photos and reading of their losses, that some Moms and Dads secretly hope that so long as the bedrooms remain as they were, the sleepyheads that rested there might return.

The black and white photographs (“I wanted to present them neutrally, without the distraction of color, so that the viewer could digest as much of the detail as possible”) capture the personality of their occupants.

There are sports trophies and hockey sticks. Cheap stereos. A Lord of the Rings poster on one wall; the Soldier’s Creed on another. The deaths date back more than a decade, which may account for a set of World Book encyclopedia on one shelf, and the not-so-flat TV screens on several others. Two belonged to women; another pair belonged to soldiers who killed themselves.

Gilbertson says his wife, Joanna, came up with the idea of capturing war by photographing barren bedrooms. Their emptiness, he adds, says as much about war as any of the photographs he made in Iraq while under contract with the New York Times. “The tragedy and the finality of this space was, to my heart, a more telling and honest explanation of what I had witnessed in Iraq than the countless photographs I had made there,” he writes. “The exploding bombs, morgues overflowing with corpses, and wounded soldiers being loaded onto helicopters were thousands of miles away. But in bedrooms like this, it felt like the conflicts were just outside, pressing against the walls.”

A website dedicated to the effort sums it up like this: “The purpose of this project is to honor these fallen—not simply as soldiers, marines, airmen and seamen, but as sons, daughters, sisters and brothers—and to remind us that before they fought, they lived, and they slept, just like us, at home.”

Hanging heavily over every photograph is the unspoken truth that while war is ignited by the old, they don’t fight it. “One thing that all the rooms here have in common is that they belonged to young people, people just out of high school, mostly, people well on their way to adulthood but still living in their parents’ homes, sleeping in single beds, often with a teddy bear or two looking over them—like children,” author Philip Gourevitch notes in the foreword. “That is who we send to fight our wars for us, our children.”

These are simply temporal temples to those who once dreamed there, frozen in pillowed amber. “Now it’s dark and I’m alone,” Brian Wilson and his brothers sang, when they were about the same age as those troops who didn’t come back. “But I won’t be afraid…in my room.”

Ashley Gilbertson is a photographer at VII Photo and is principal at Shell Shock Pictures

Mark Thompson is a Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist who has covered national security in Washington since 1979, and for TIME since 1994.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com