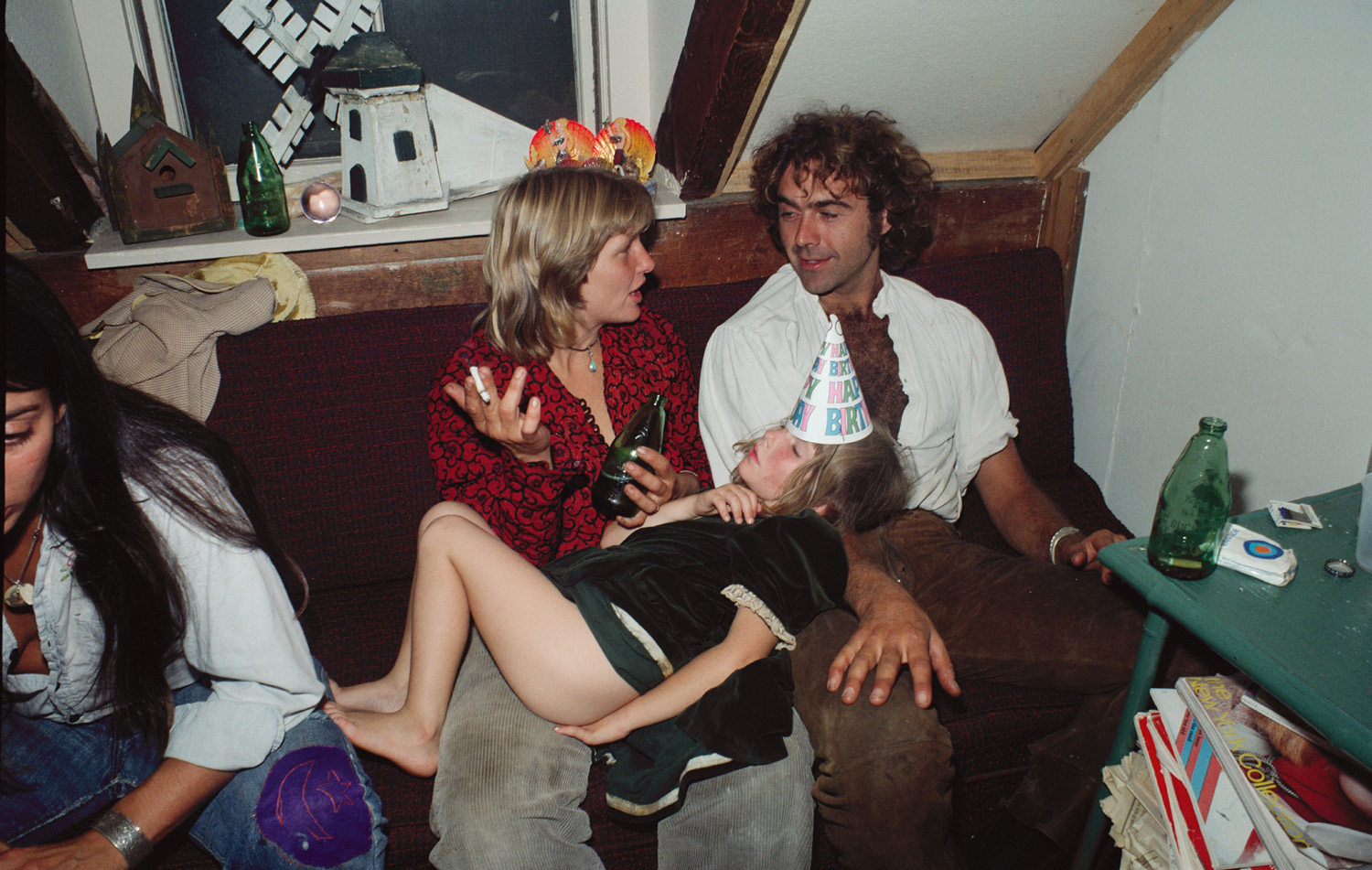

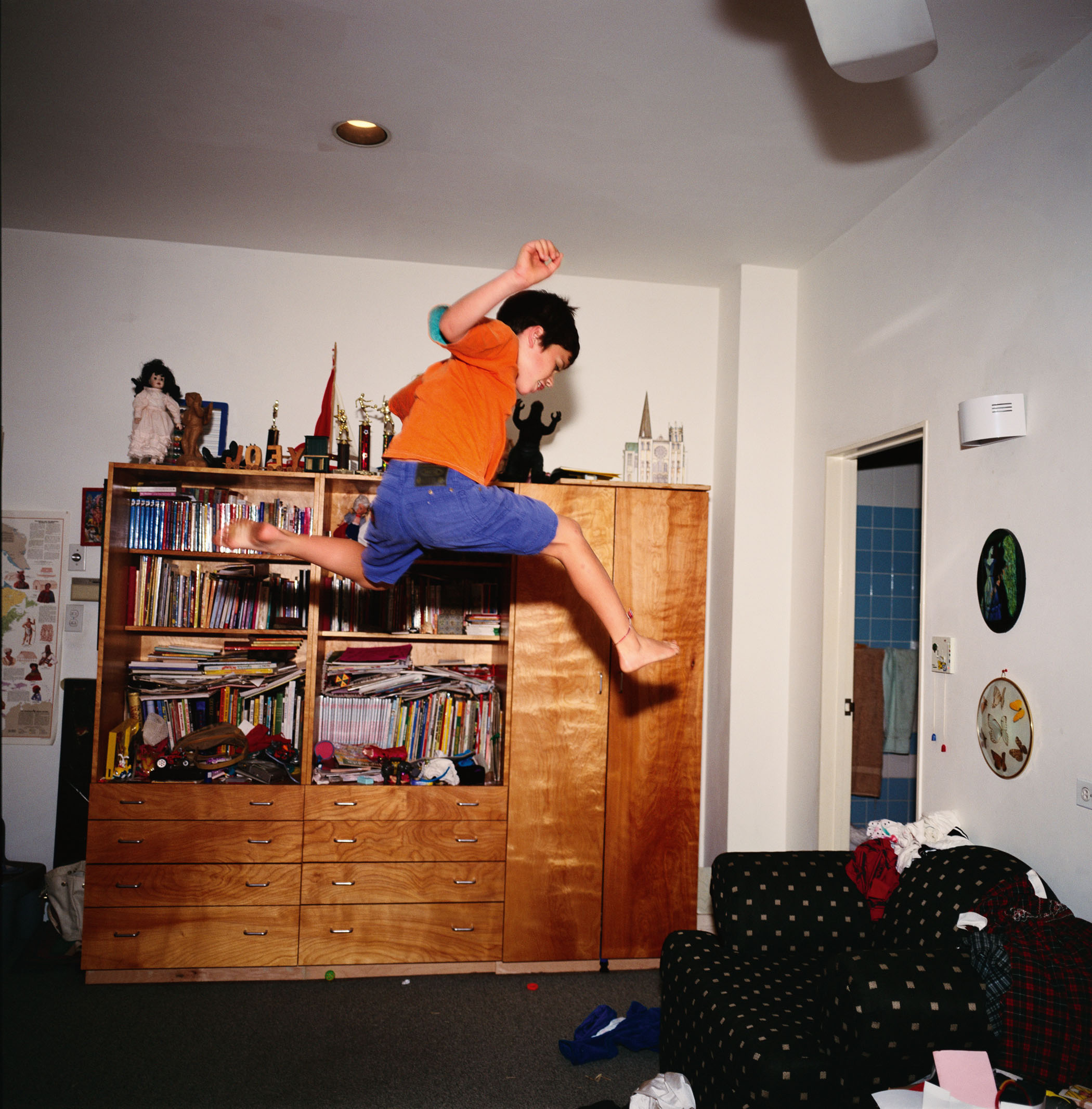

Nan Goldin’s first book in 11 years, Eden and After, may look sweet from the outside, but underneath the playful photos of children runs a deeply woven fairy tale about the joy and power of childhood and the inevitable end to the freedom that comes with it.

It would be easy to think of Eden and After as a family album, but nothing is easy in Goldin’s work. From the searing honesty of her landmark 1986 monograph The Ballad of Sexual Dependency and the often-harrowing portraits found in her photographic diaries — chronicling addiction and the lives of the willfully marginalized — Goldin’s pictures never flinch from stark reality. In photographing children, Goldin says, she’s exploring independent beings, moving freely through their own existence before they’re burdened with self-consciousness as adults.

“It’s really about the autonomy of children,” Goldin told TIME, speaking from her home in Paris. “A book about family would be very different, for me. We weren’t even going to include image of parents at first. When we did, the page count of the book went way, way up.”

At a hefty 373 pages, Eden and After is broken down into small, narrative chapters, charting kids’ formative years in abstract, dreamlike phrases: “Mirror School,” “Bears Come Tooling,” “Lion’s Den.”

“This is the most narrative of my books,” she says, “because I’m telling a story about children as these magical beings that come from another stratosphere and arrive on the planet. I started to believe, while I was making the book, that children come from somewhere else, and the reason we don’t remember our first few years is because [while we’re very young] we still remember where we came from.”

Goldin makes it clear that the philosophy she developed over the course of compiling Eden and After has nothing to do with God or any other higher power. Children are beyond that.

In her photographs, Goldin is seeking out the secrets children seem to hold, and much like she exposed the raw and unnerving inner lives of drag queens and drug addicts, here she hopes to reveal something about children that is both deeply hidden and transparently evident.

“People would say to me, ‘children know everything,’ and I thought it was sentimental crap,” she said. “But I really started to believe it. If you look at some of the pictures of the children when they’re only three weeks old, the look in their eyes is like they’re winking — like they know everything. And then the process of growing up is being made to forget it all, as children are socialized.”

The flip side of Goldin’s fairy tale is her generally negative outlook on the world at large, and her growing belief that humanity, or what’s left of it, is in a period of serious decline. While the book has been on the shelf for just over two weeks, she’s already been faced with a fair degree of criticism over her unflinchingly uncensored photographs. The objections to the amount of nudity in the book strike Goldin as particularly misguided, and more damaging to a child’s mentality and self-image than the perceived protection that censorship implies.

“There’s a certain amount of nudity that people find morally offensive, and I really worry for the children of those people,” she said. “There’s nothing worse you can do than make a child ashamed of their body. I think that’s what a lot of society and family is about: taking away children’s pride and freedom in their own bodies. Think about it. You don’t meet so many adults in our society who are truly comfortable in their own bodies. That comes from fears and that comes from society. We’re all born naked, so how could pictures of nude pregnant women and naked children be offensive? I think that’s perverse.”

Goldin says she’s never intended any of her work to be overtly political–but the personal, she notes, is always political. The children she photographs in Eden and After are her nieces, nephews, godchildren and cherished children of close friends, but their attitudes and origins are entirely their own. The pictures in the book span nearly a half-century, long enough for some of the children she photographed in the 1970s to have grown up– and to have forgotten

that magical place they may have come from.

Eden and After is childhood as Nan Goldin witnesses it: that is, as a joyful calm before the exasperation of adulthood. As with so much of Goldin’s work, the images straddle the line between profoundly revealing and too-close-for-comfort. What she accomplishes here, in her latest book, might feel softer around the edges than her previous projects, but at its core Eden and After is a sincere and complicated ode to the end of innocence.

Nan Goldin is a photographer based in New York City, Paris and Berlin. Her latest book Eden and After was published by Phaidon.

Krystal Grow is a writer for TIME LightBox

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How Donald Trump Won

- The Best Inventions of 2024

- Why Sleep Is the Key to Living Longer

- Robert Zemeckis Just Wants to Move You

- How to Break 8 Toxic Communication Habits

- Nicola Coughlan Bet on Herself—And Won

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Contact us at letters@time.com