The first time I visited Aghanistan in May 2000, I was 26 years old, and the country was under Taliban rule. I went there to document Afghan women and landmine victims. At the time, the Taliban had banned photography of any living being, so I snuck around with my cameras in a bag, visited people in their homes in Kabul and the provinces, and claimed I was photographing destroyed buildings left by over two decades of war in the country. There were almost no foreigners in Afghanistan then; electricity was rare, television was banned, and my only contact with the outside world was through BBC dispatches on a short-wave radio and through UN officials based in Kabul.

The Taliban rose to power in 1996, vowing stability and an end to the violence raging across the country between warring mujahedeen factions, and to implement rule by Sharia law, or strict Islamic rule. Despite decades of war, Afghans were the most hospitable people I had ever met. I remember driving through the dusty villages of Logar and Wardak provinces, along narrow streets lined with traditional clay compounds, where word spread quickly that a foreigner was passing through. We stopped by people’s homes unannounced, and within an hour, a lavish meal of whatever the family could muster from the garden appeared before us: freshly whipped butter, carefully picked greens, juicy tomatoes, freshly baked bread, and on the rare occasion, meat. People offered whatever they could, because hospitality was an integral part of the culture. I met brave women who were teaching in secret schools for girls–education for girls over 10 was also banned under the Taliban–in basements and behind heavy curtains in their homes, and interviewed educated, professional Afghan women who were relegated to a life behind closed doors and without work.

By the time the United States went to war with Afghanistan in the fall of 2001, I had made three trips to the country. I covered the fall of the Taliban in Kandahar, and have been returning routinely for the past 14 years.

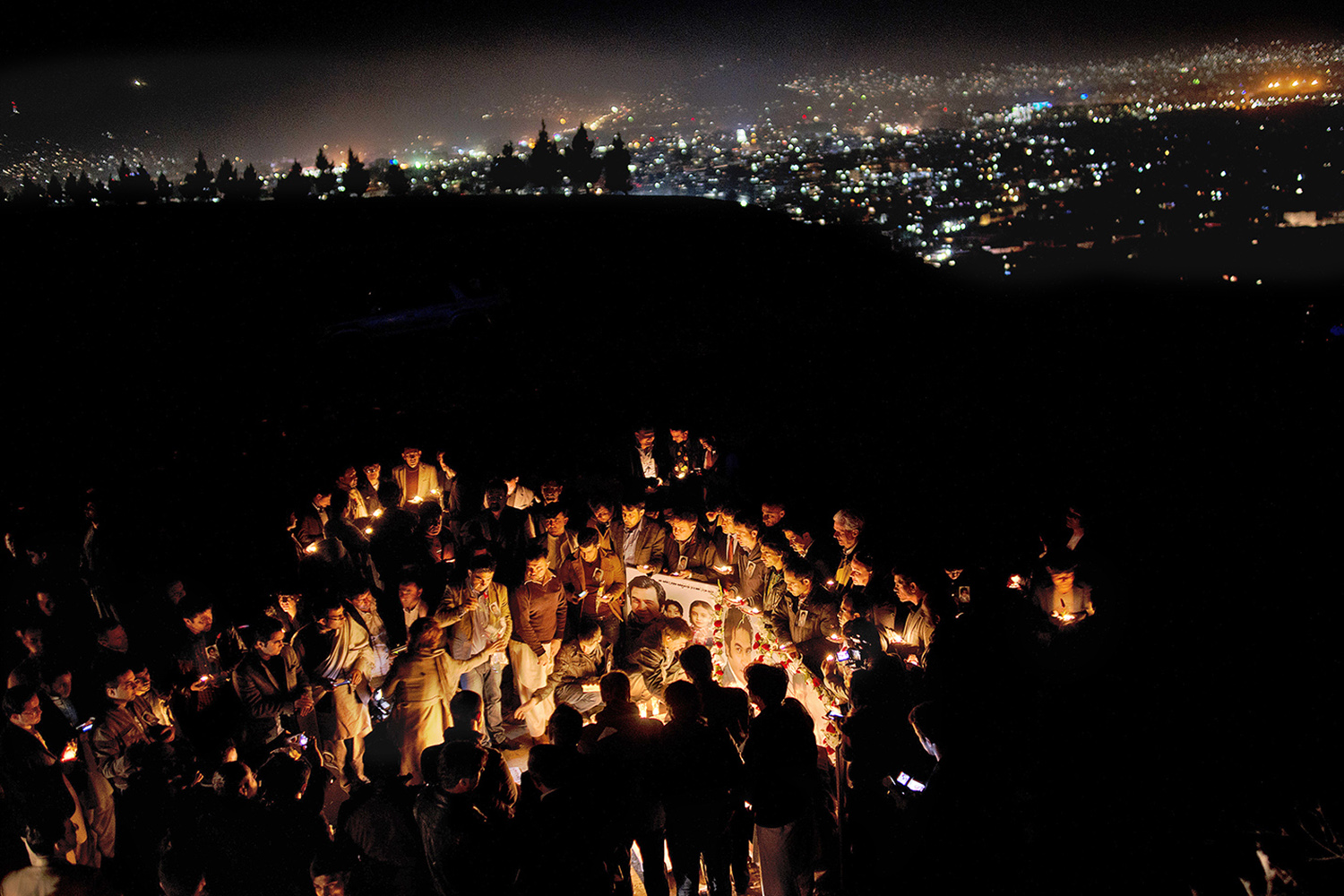

Last week I traveled to Kabul to photograph the violence surrounding the upcoming presidential elections, and it was the first time in well over a decade that as the plane skimmed the snow-capped mountains surrounding Kabul, my normal exhilaration was replaced by fear. Kabul used to be one of the safer places in the country, but the week before I traveled, the Taliban–who ironically had been responsible for bringing stability to the country less than two decades before—was slaughtering civilians and security forces in the capital. They vowed to disrupt elections with an increase in violence: a Swedish journalist was executed by insurgents in broad daylight in a neighborhood where many foreign journalists and aid workers reside; four gunmen attacked the luxurious Serena hotel on the eve of Nowruz, the Persian new year, killing nine, including AFP journalist Ahmad Sardar, his wife, and two of his three children. All three of Sardar’s children, ages 5, 4, and 2, were shot in the head as their mother pleaded for their lives. Only the two-year-old survived. I landed in Afghanistan in the wake of these brutal, merciless massacres, knowing the goal posts had changed—no one was off limits to the Taliban.

In the subsequent six days I was on assignment, there were three major attacks—two on the Independent Electoral Commission, and one on a guest house for foreign aid workers. Four- and five-hour gun battles between Afghan security forces and the Taliban were becoming commonplace in the heart of the city, forcing foreigners inside their compounds, and creating terror afresh among Afghans.

But Afghans were undeterred by the Taliban’s seemingly endless supply of suicide bombers. Lines of men and women continued to line up at IEC centers to register to cast their votes for a new president on April 5th. Day after day, they braved the Taliban threats to derail elections because they want a say in their country’s future after 35 years of civil war, occupation, and senseless violence.

On March 27, I traveled with presidential candidate Zalmay Rassoul and his running mate, vice-presidential candidate, Habiba Sarabi, to Mazar-e-Sharif for an election rally. Habiba was the first female Afghan governor in the country, in Bamiyan Province, and is the first woman running for vice-president with a chance at winning. I spent some time photographing the crowd and the candidates from the stage, and eventually made my way down to the grounds of the stadium to photograph the hundreds of Afghan women in attendance.

I was shooting when, suddenly, the male supporters in the stadium went wild, waving their arms, cheering and screaming at the podium, which was obstructed by layers of security. I assumed the crowd was cheering for Rassoul. I weaved through the security perimeter on stage to get a better look at the presidential candidate–and to my surprise, the speaker was Habiba. Tens of thousands of Afghan men were cheering for a woman, an Afghan woman, running for the second highest office in the country. And for a moment, I knew the Afghan people had won. The Taliban could force them inside no longer.

Lynsey Addario is a photographer based in London and a frequent contributor to TIME.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com