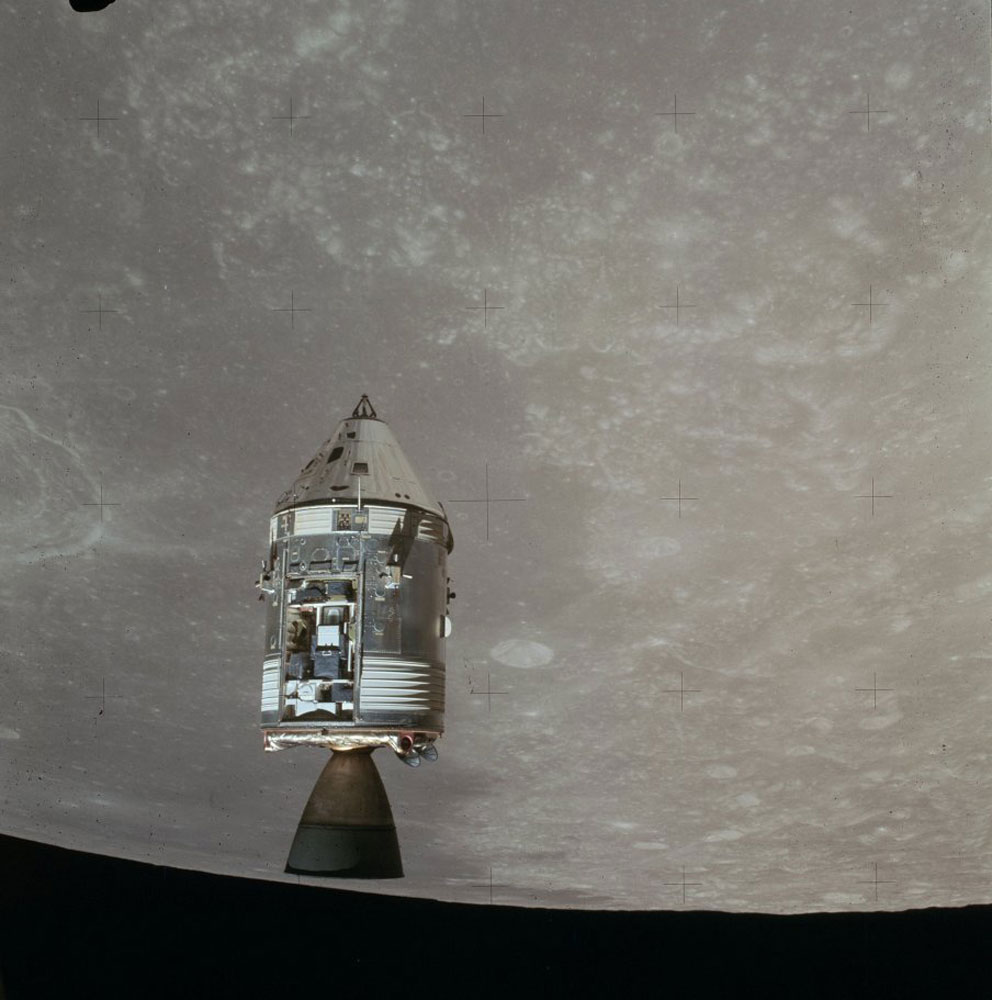

The machines that made the Apollo program a success were, on the whole, huge. The Saturn V rocket rocket stood 363 ft. (111 m) tall. The scaffold-like gantry that serviced it measured nearly 400 ft. (122 m). The slow-motion crawler that took the rocket out to the launch pad weighed a tidy 6 million lbs. (2.7 million kg). But one of the most important machines that flew on any flight could fit in the astronauts’ hands, and weighed just 1.8 lbs. (0.8 kg)—even less in lunar gravity. It was the purpose-built, Hasselblad 500 EL camera, only 14 which ever flew to the moon, and only one of which—used by the late Jim Irwin, lunar module pilot for the July 1971 Apollo 15 mission—is known to have made it home. Once the last film canister had been removed, the cameras were supposed to remain on the surface to help shave weight during lunar liftoff.

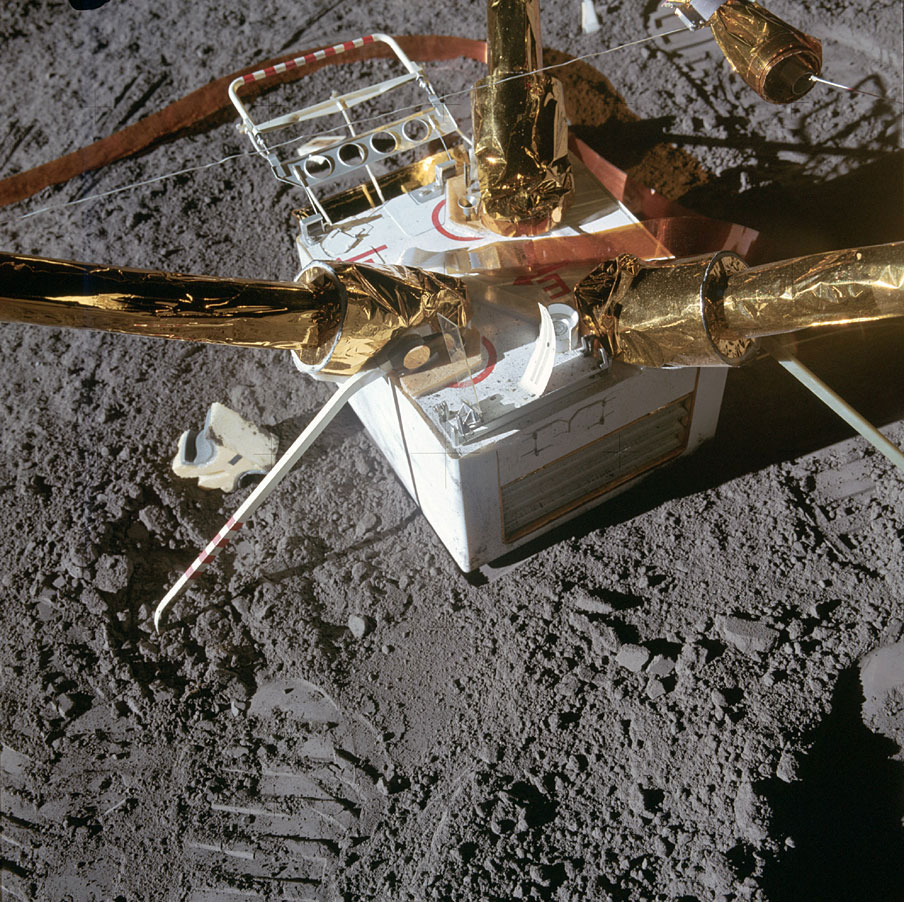

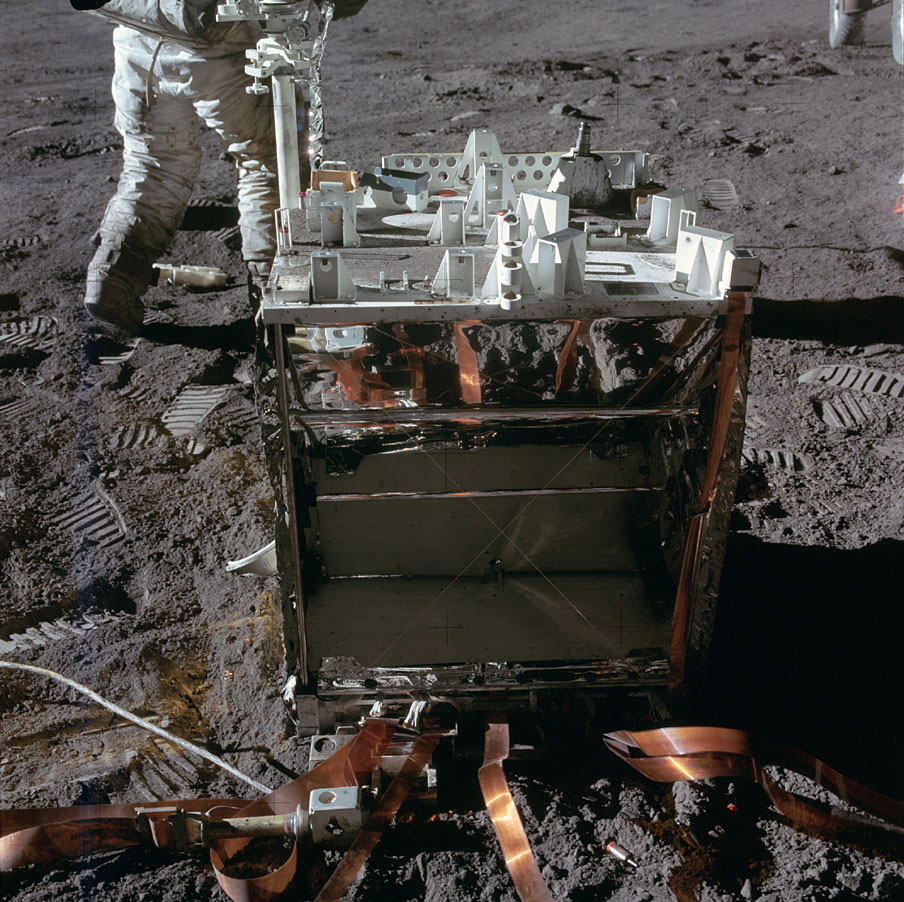

Irwin’s camera is now being auctioned off by an Italian collector of historical artifacts at the Westlicht Gallery in Vienna, which expects it to go for $200,000 to $270,000. That may be a lot to pay for a camera that will never take another picture, but it’s nothing at all considering the history this particular Hasselblad captured—and made. The lunar Hasselblad had only a few key differences from Earthly models. Its knobs had to be especially well-sealed against moon dust, which is finer than confectioner’s sugar and has a nasty habit of jamming unprotected gears.

An ultra-thin film had to be invented for the missions, allowing 240 exposures to fit into a single magazine, which minimized the number of times the astronauts would have to change canisters. The cameras had the same F-stop, focus and depth controls any other camera does, but in this case, a small post poked from each knob, making it easier for astronauts wearing bulky lunar gloves to turn them with a one-finger-push instead of a five-finger twist.

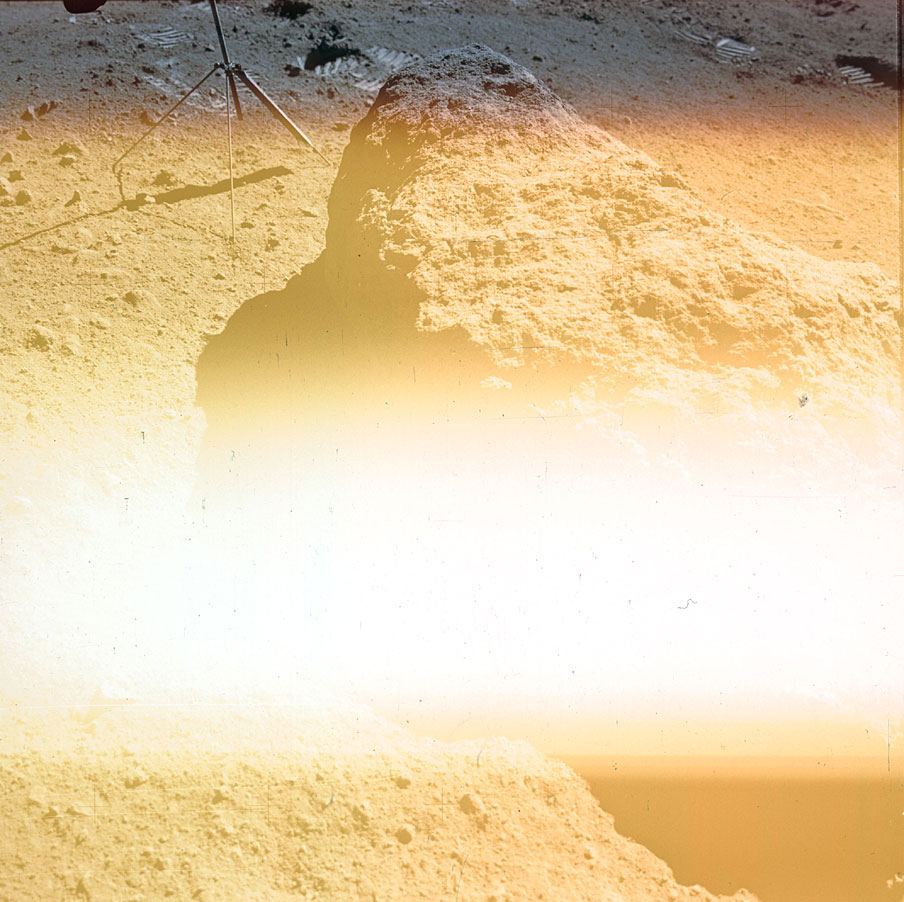

“The only major issue we had to deal with was the sun,” Apollo 15 commander Dave Scott told TIME in a recent conversation. On the airless moon, sunlight simply doesn’t behave the way it does on a world in which the atmosphere creates all manner of colors, shades and other effects. “You were either pointing up-sun, down-sun or cross-sun and we had to adjust the shot to accommodate that. Otherwise, there was little we did that was different from what you’d do on Earth.”

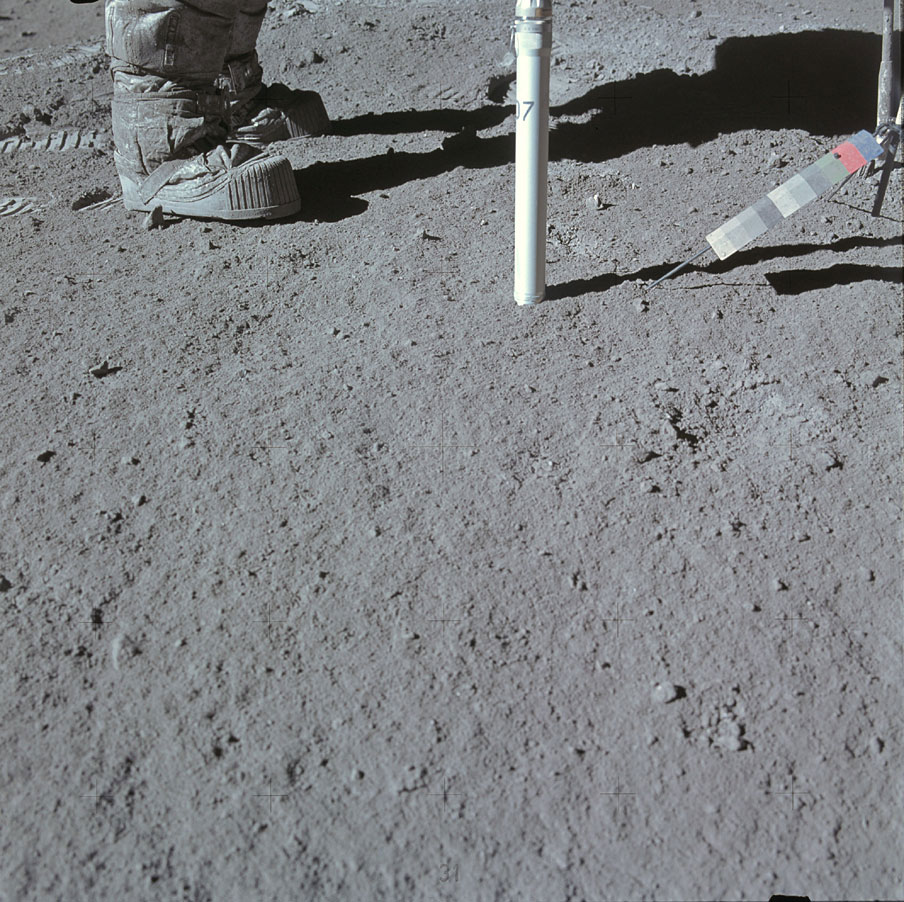

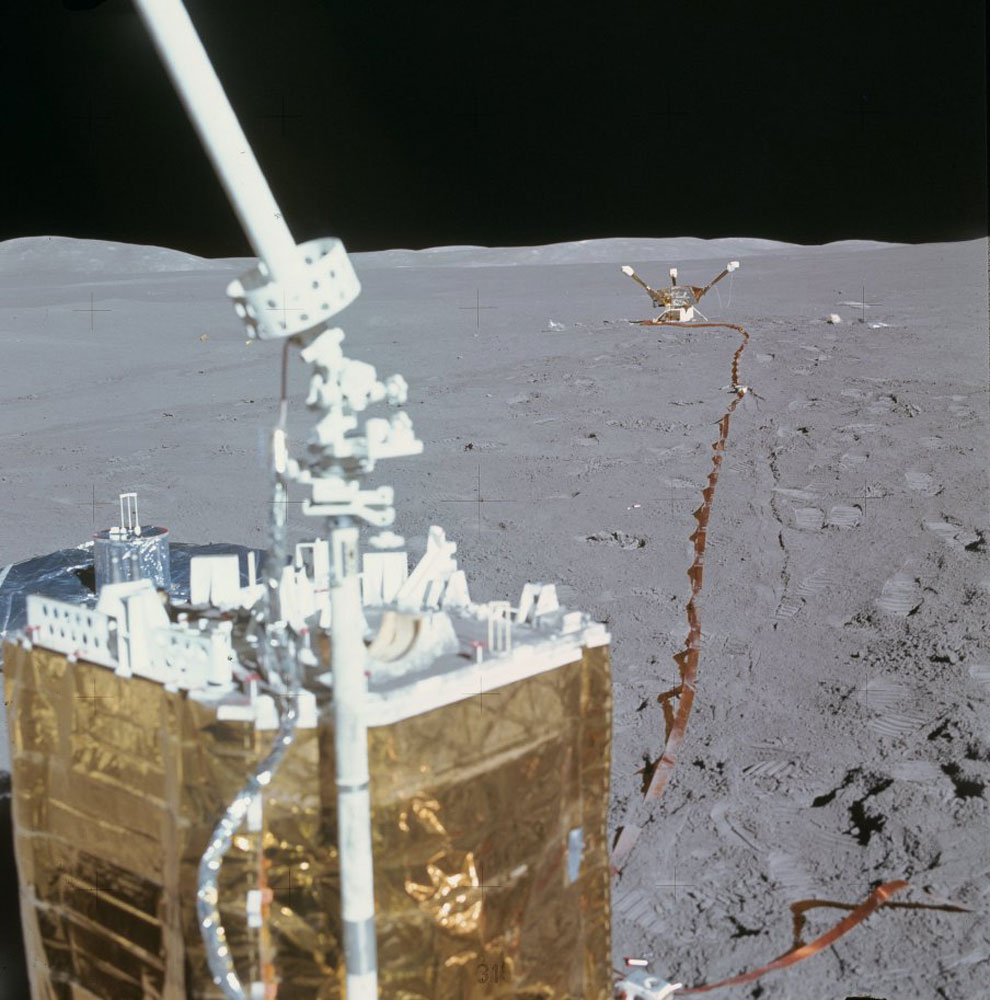

But if the point-focus-and-shoot process was familiar, the things the astronauts’ photographed were radically different.The moon pictures that have stuck in the popular imagination are typically the glamour shots—the glittering lunar module, the spindly moon car, the saluting astronauts, the rising Earth. But the ones the scientists were interested in were all about geology. Every single one of the 843 lbs. (342 kg) of rocks that the six Apollo landing missions returned had to be identified in terms of exactly where it was found, the better to distinguish the properties of samples collected on foothills or mountains from those on plains or crater rims. And that meant a lot of scene-setting pictures. “Every time I stopped the lunar rover, I’d do a switch-off and a clean-up and Jim would get out and do a 360-degree pan,” says Scott. “He just nailed it every time. I did OK, but Jim left us a real legacy.”

The very ordinariness of some of Irwin’s pictures is what makes them feel especially real. It’s not just the shots in which the rover is badly framed or a piece of Scott intrudes from a corner—pictures that never made it into NASA’s carefully curated press releases. It’s the ones of the soil that also include crumpled bits of film packaging left on the ground—lunar litter indistinguishable from the Earthly variety nearly every tourist has been guilty of dropping at some point. “When you’re onsite and doing things, you don’t think about photographing for the ages,” Scott says. “We just took pictures of everything we could.”

All of Scott’s and Irwin’s pictures—as well as those from Apollos 11 through 17—survive on NASA’s Apollo Lunar Surface Journal, a searchable site that also includes air-to-ground transcripts and extensive captions explaining the images. The descriptions are technical—even arid, sometimes—befitting the exercise in physics and engineering that all of the moon missions, regardless of their drama, really were. The humanity lies elsewhere—in the very improbability of the pictures, taken at a time when Americans went to the moon simply because they decided to do such an outrageous thing.It lives too in the memories of the surviving men who made the journeys and in what they can pass on. Scott currently lectures at Brown University, teaching Millennial students something about the last millennium’s culture,when explorers worked with engineers who worked with politicians who worked with the public to collaborate on achieving something fleeting but wonderful.

“We got involved in this thing and it goes so fast and then it’s over,” Scott says. “Back in test pilot school, we had automatic cameras in the cockpit to photograph everything, so that when we got back we could remember what happened.” The hand-operated cameras Scott and Irwin and the others used serve the same function, but in this case it’s not just the pilots who get to remember, it’s all of us.

The 70mm Hasselblad used on the Apollo 15 mission in 1971 will be auctioned at Vienna’s Westlicht Gallery on March 21, 2014.

Jeffrey Kluger is an editor-at-large at TIME, overseeing the magazine’s science, health and technology reporting.

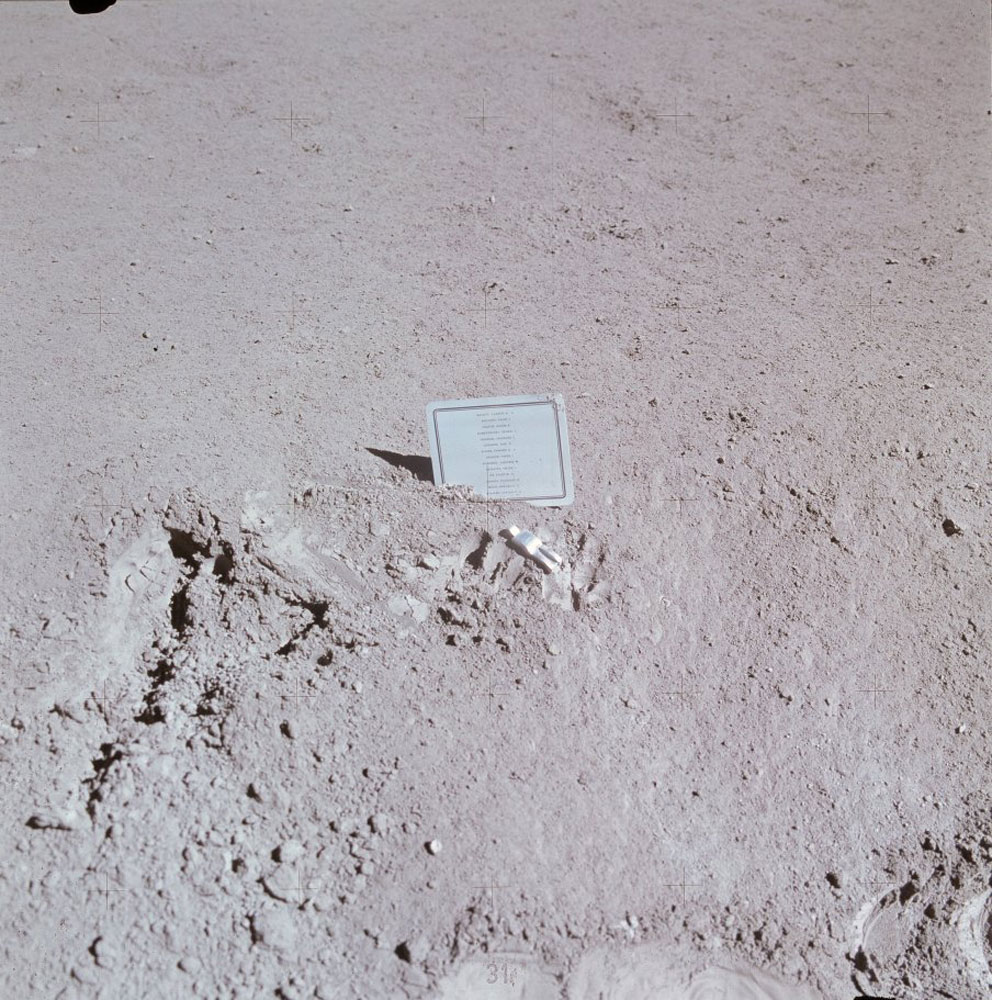

![A microfilm cassette lies in the lunar soil, a discarded—and yet priceless—bit of rubbish. In his book "To Rule the Night,," Irwin wrote, "There were a number of things we left on the Moon purposely. I left some medallions, flat pieces of silver with the fingerprints of Mary [his wife] and our children. And as a result of a letter that I got two months before launch, I also left a small portrait of J. B. Irwin. A young lady sent me a picture of her father, J. B. Irwin, saying that he had talked about his desire to go to the Moon all his life. He died at seventy-five, before the first manned landing. I thought it would be a gracious gesture to take J. B.'s picture and leave it on the Moon." And so it was.](https://api.time.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/apollo-15-hasselblad-moon-10.jpg?quality=75&w=2400)

More Must-Reads from TIME

- How the Economy is Doing in the Swing States

- Harris Battles For the Bro Vote

- Our Guide to Voting in the 2024 Election

- Mel Robbins Will Make You Do It

- Why Vinegar Is So Good for You

- You Don’t Have to Dread the End of Daylight Saving

- The 20 Best Halloween TV Episodes of All Time

- Meet TIME's Newest Class of Next Generation Leaders

Write to Jeffrey Kluger at jeffrey.kluger@time.com