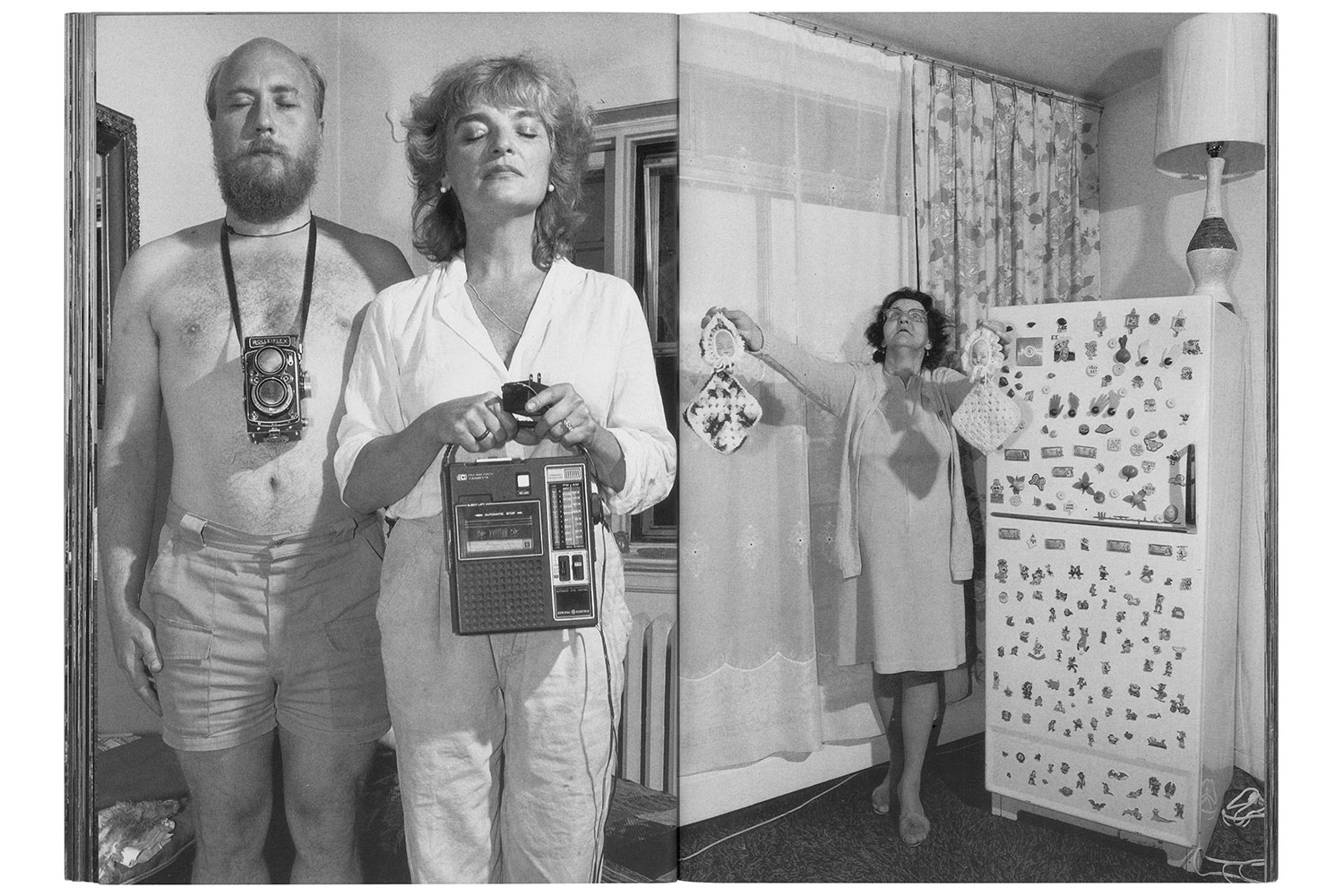

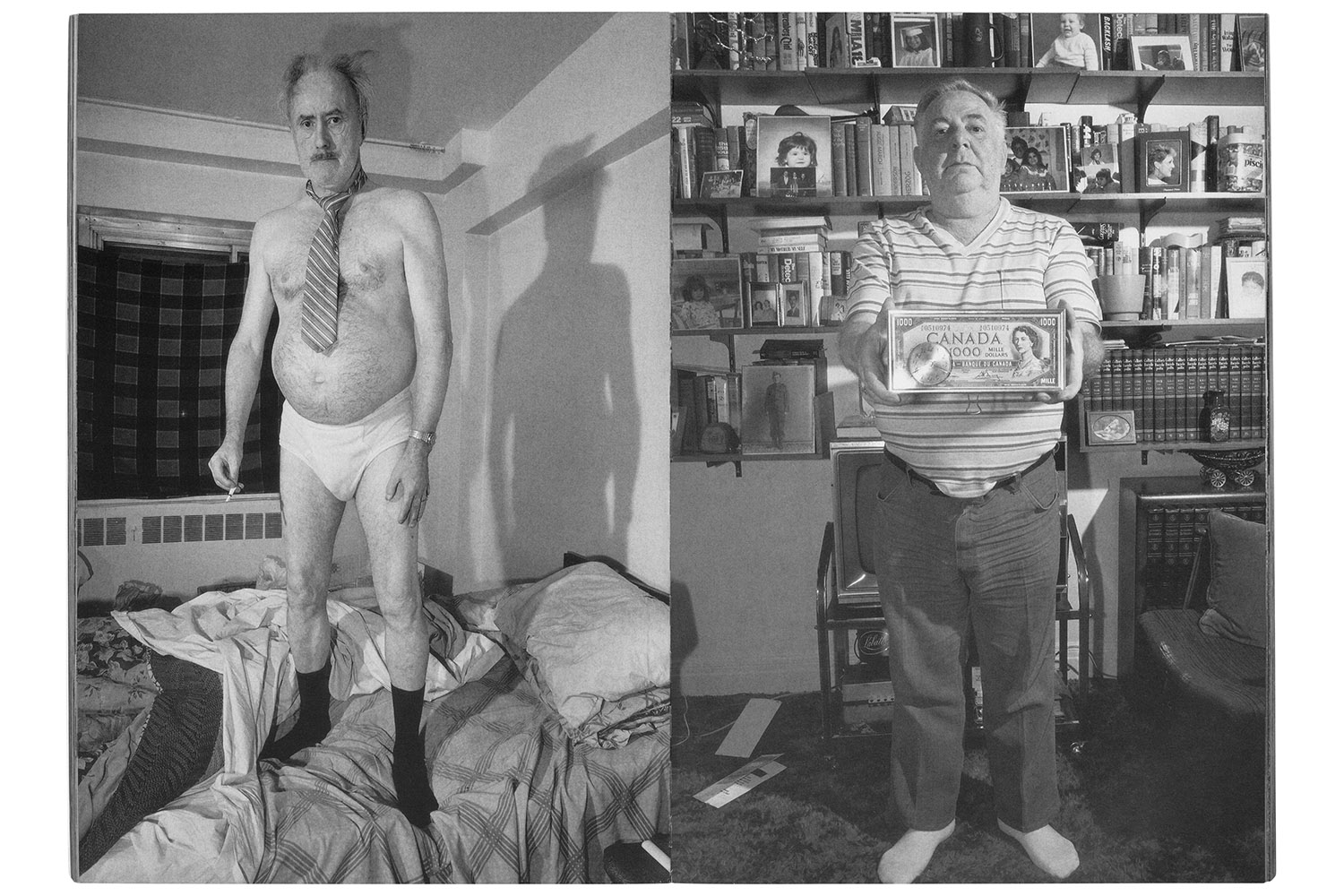

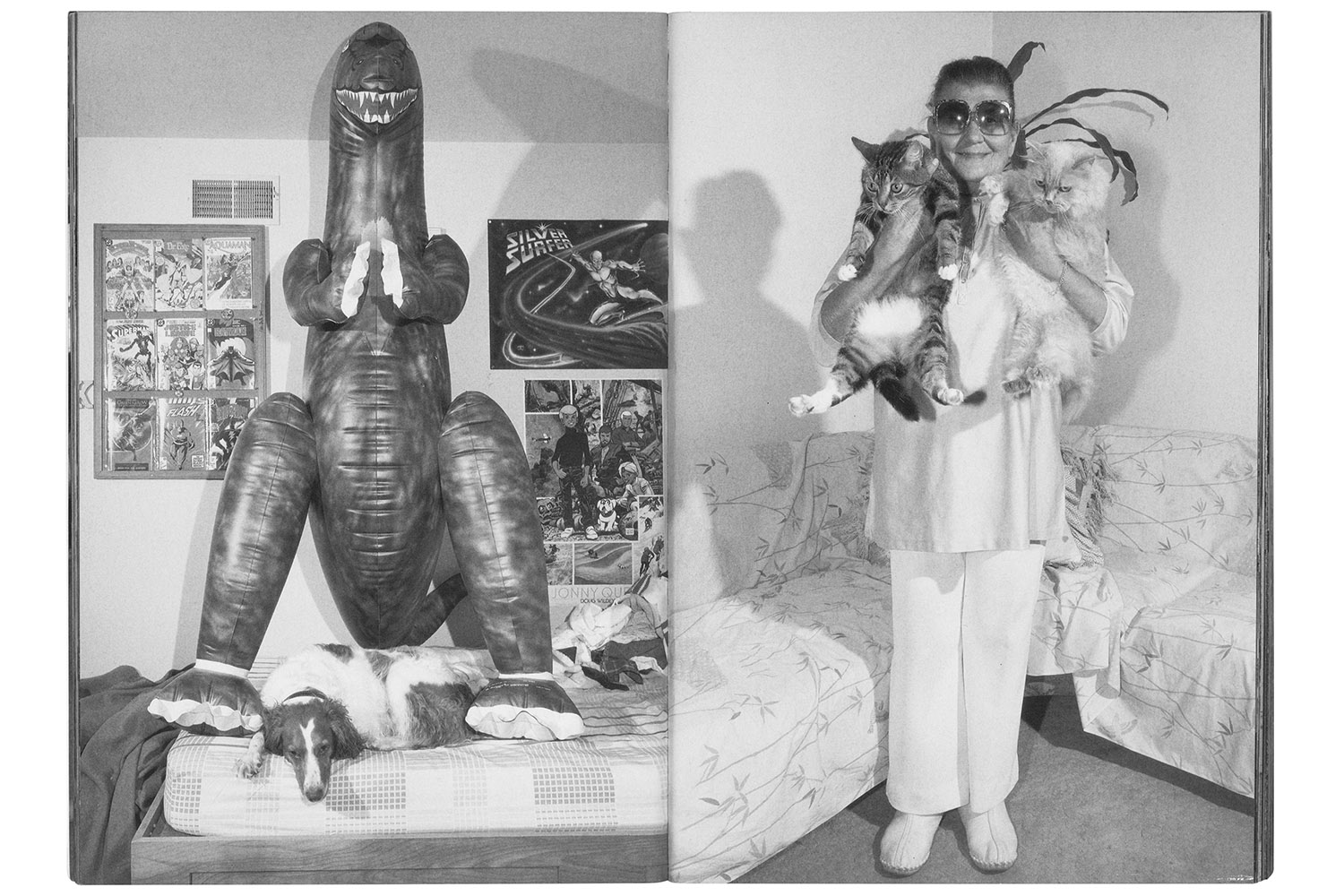

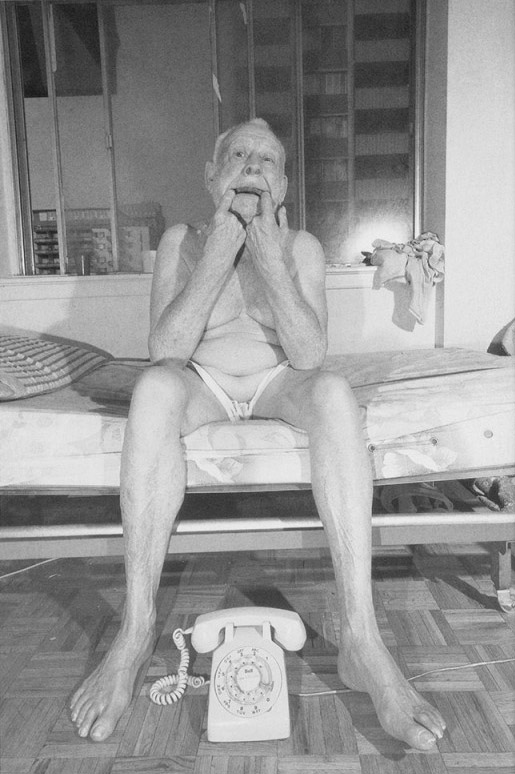

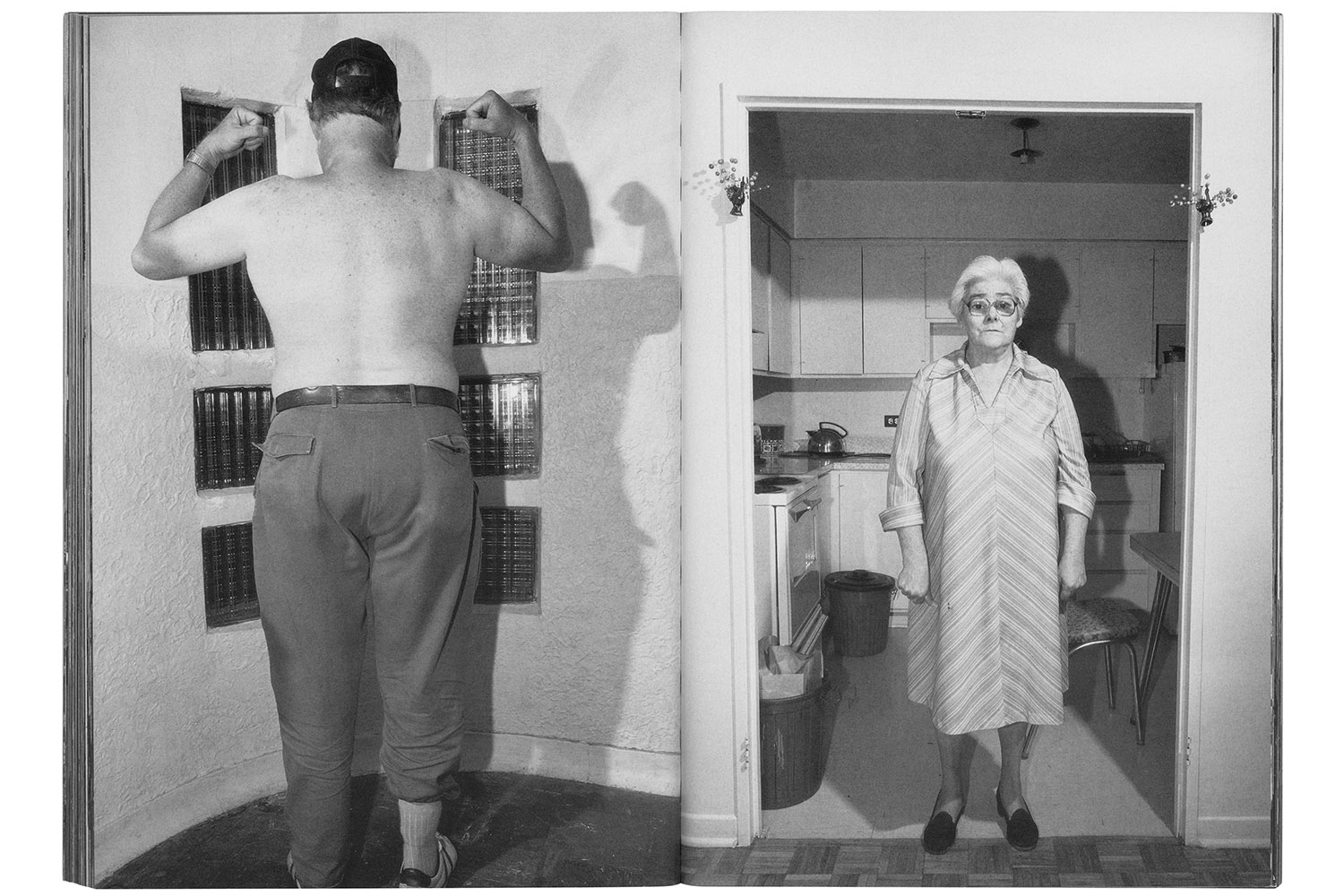

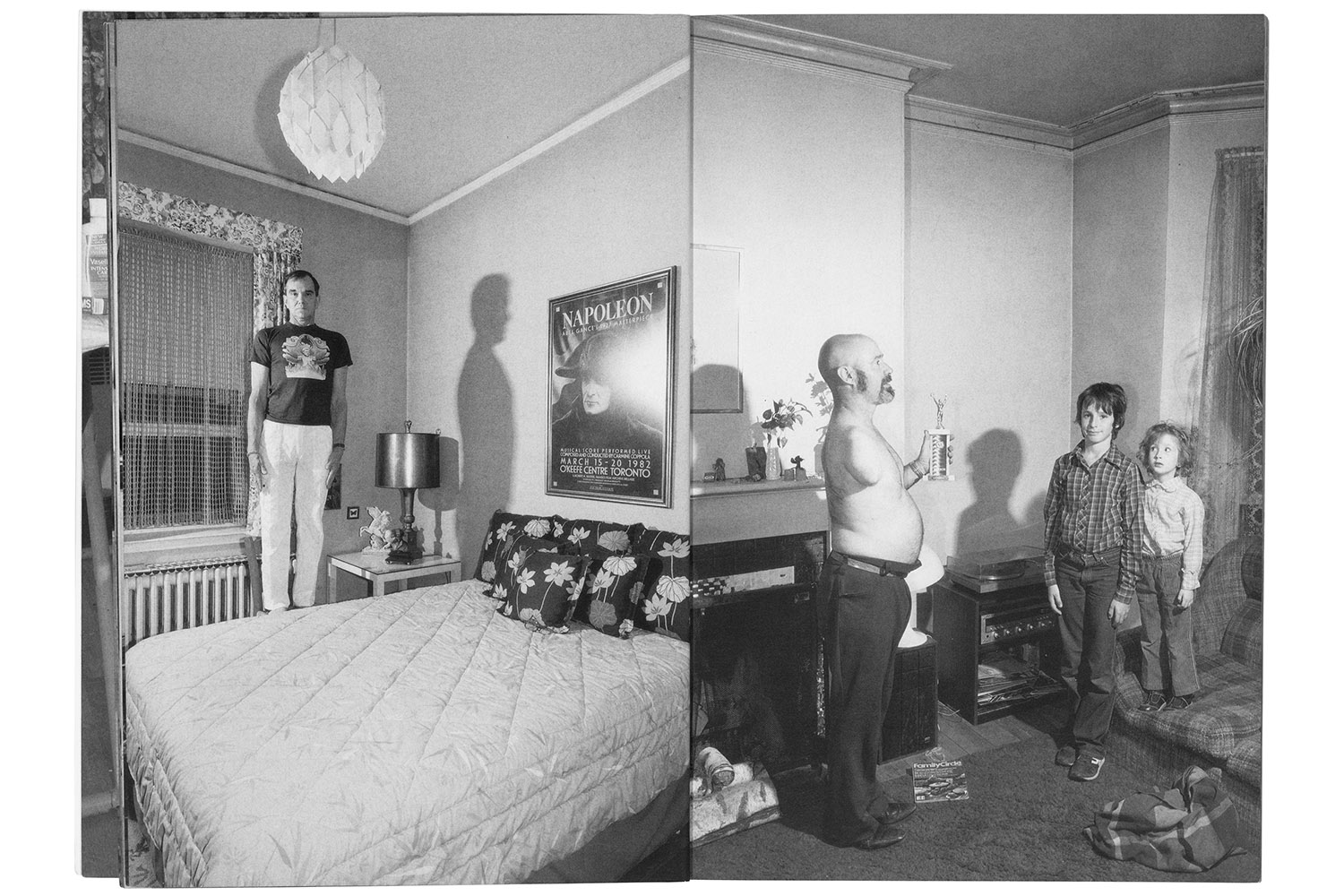

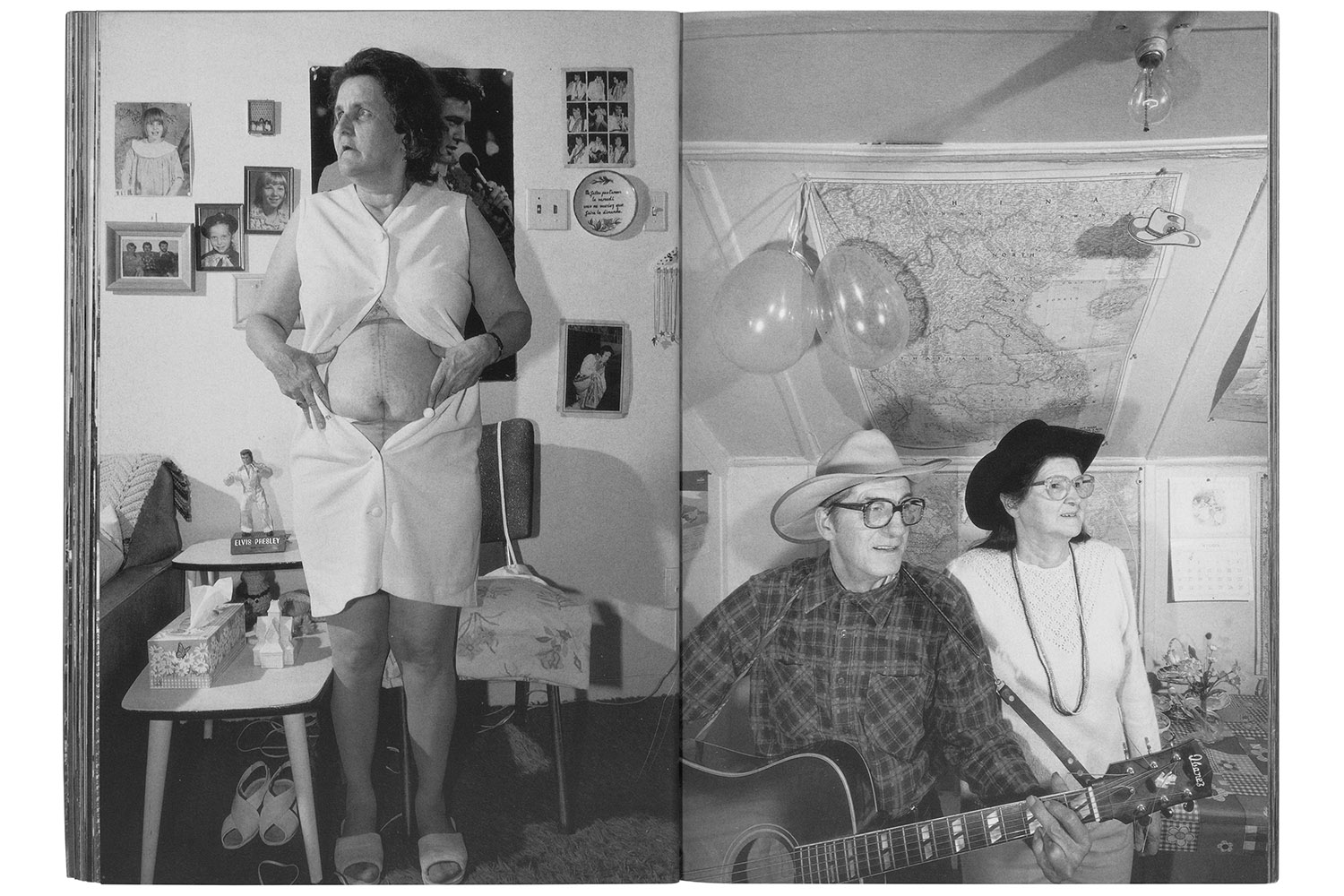

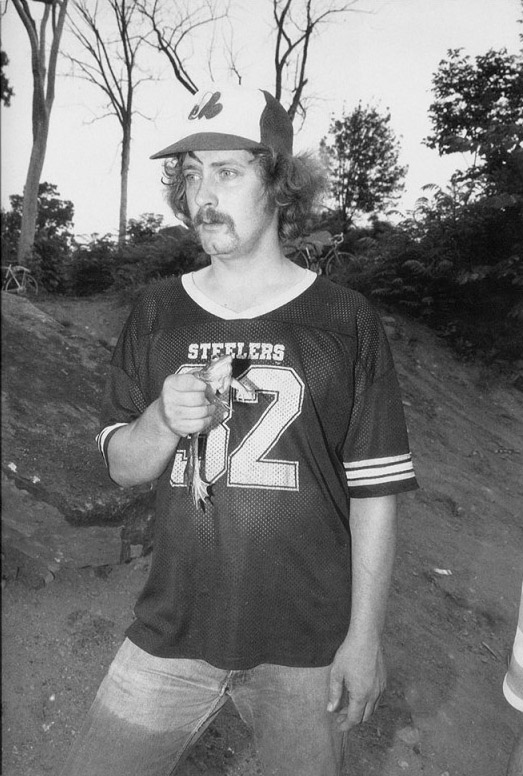

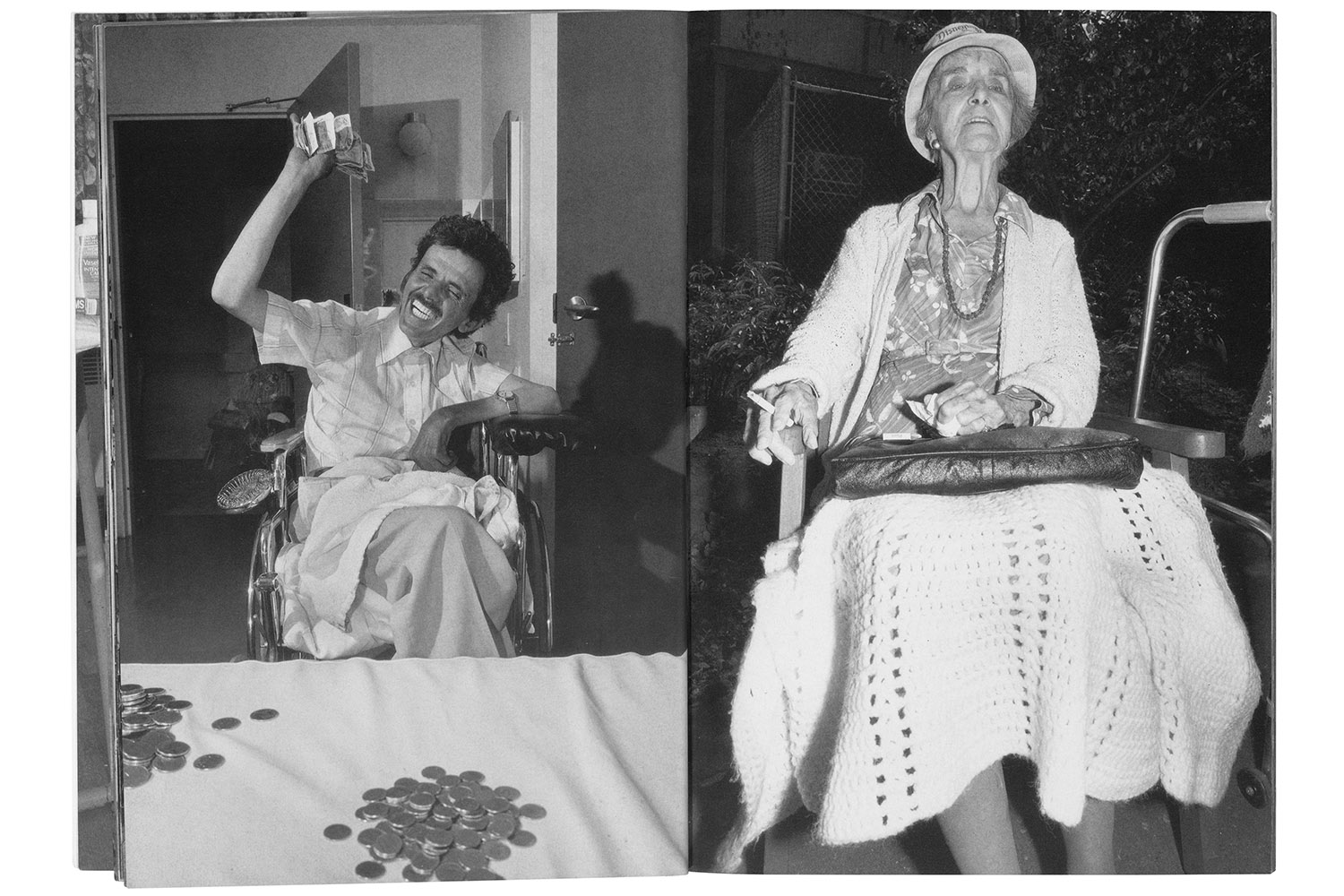

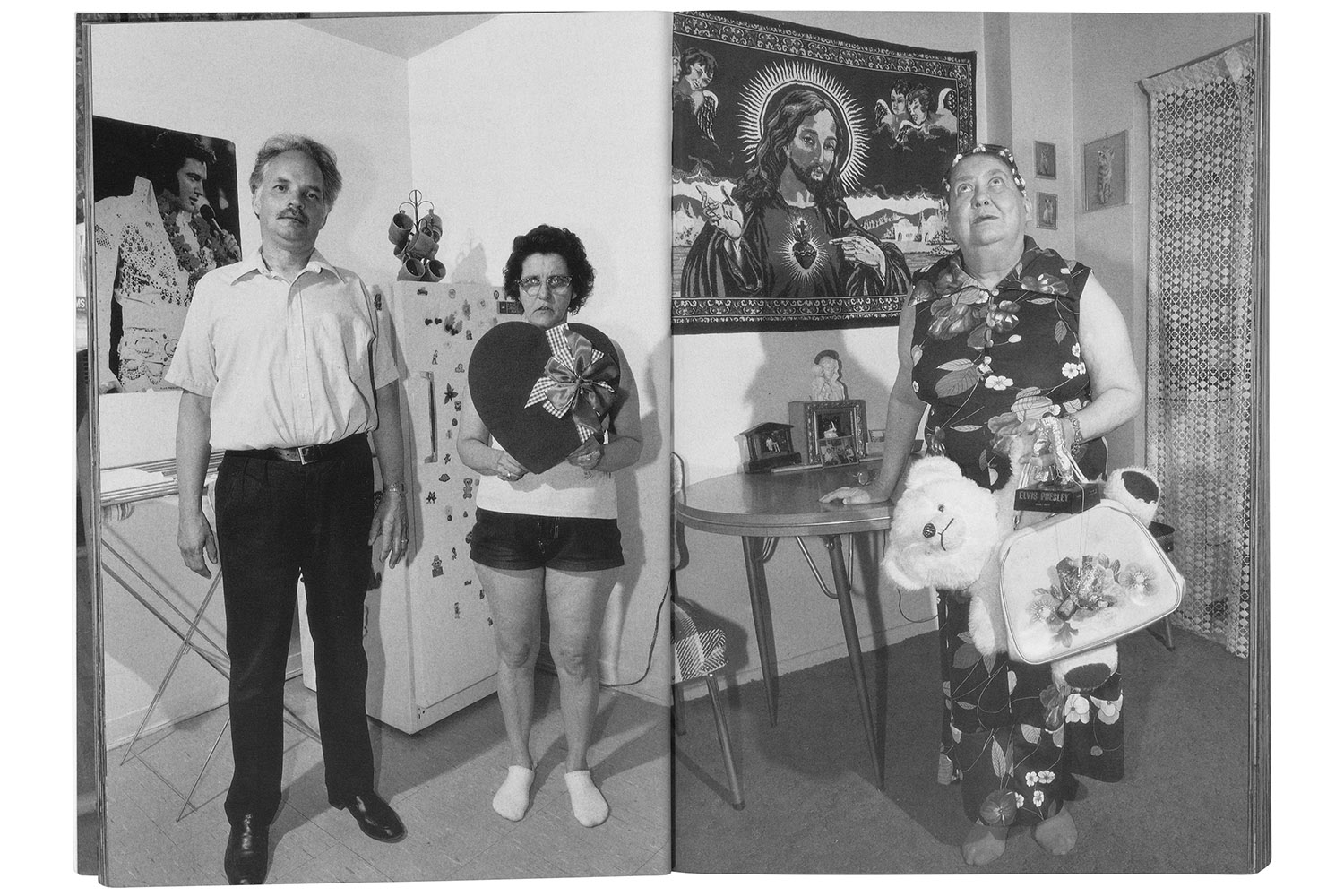

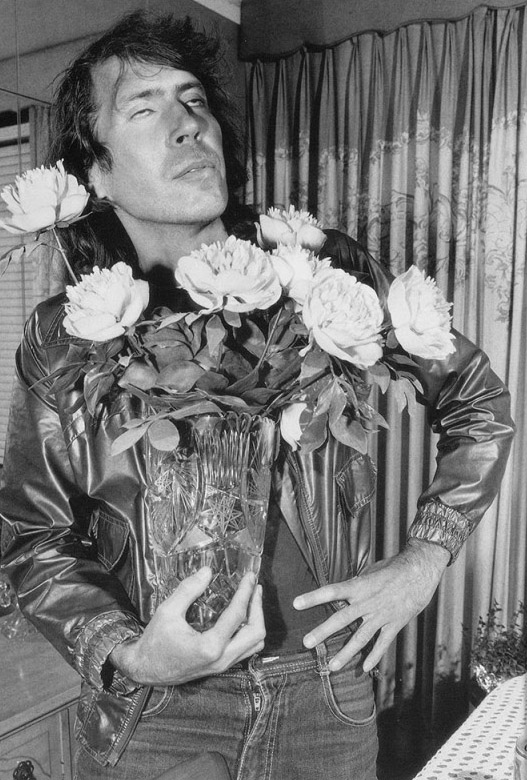

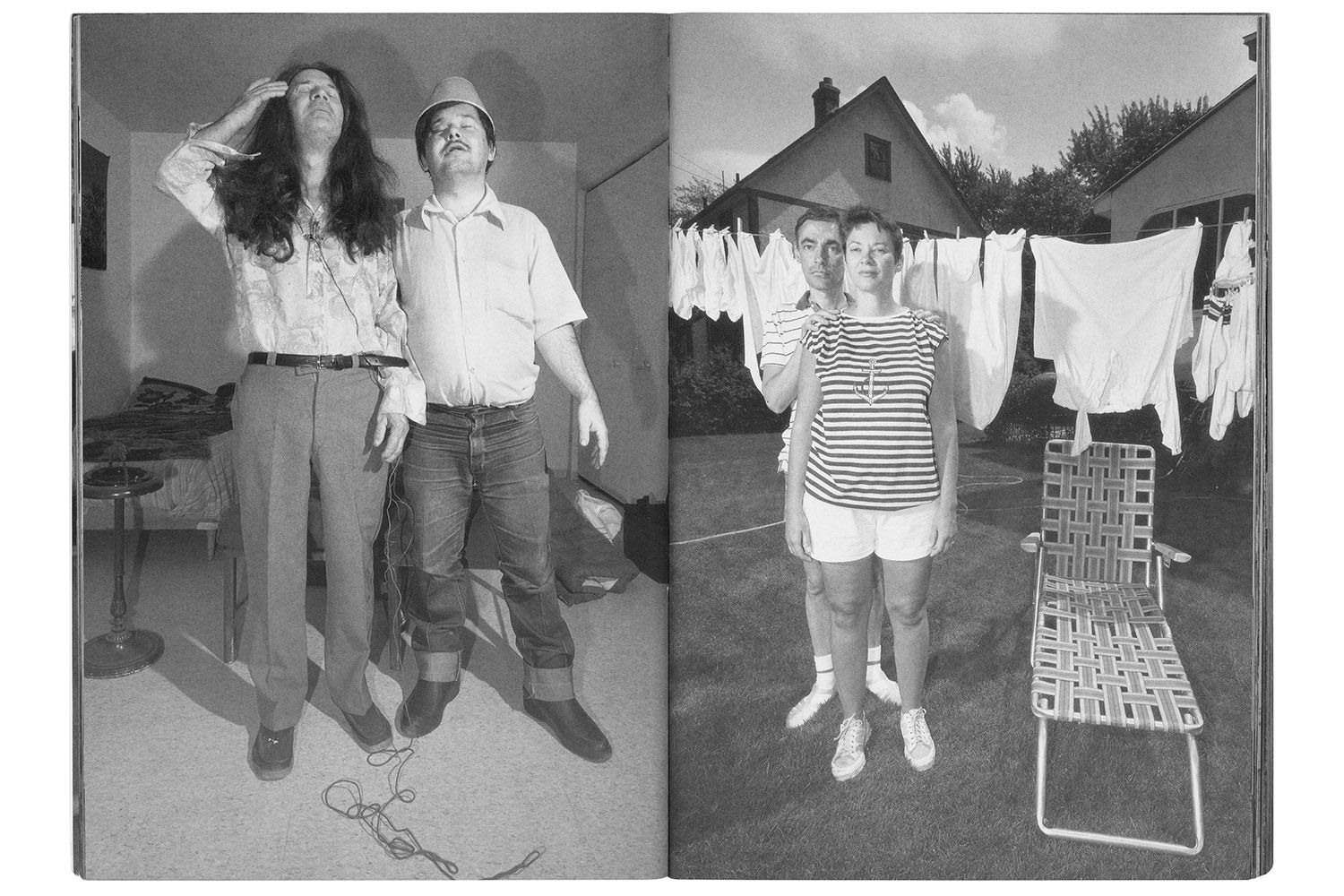

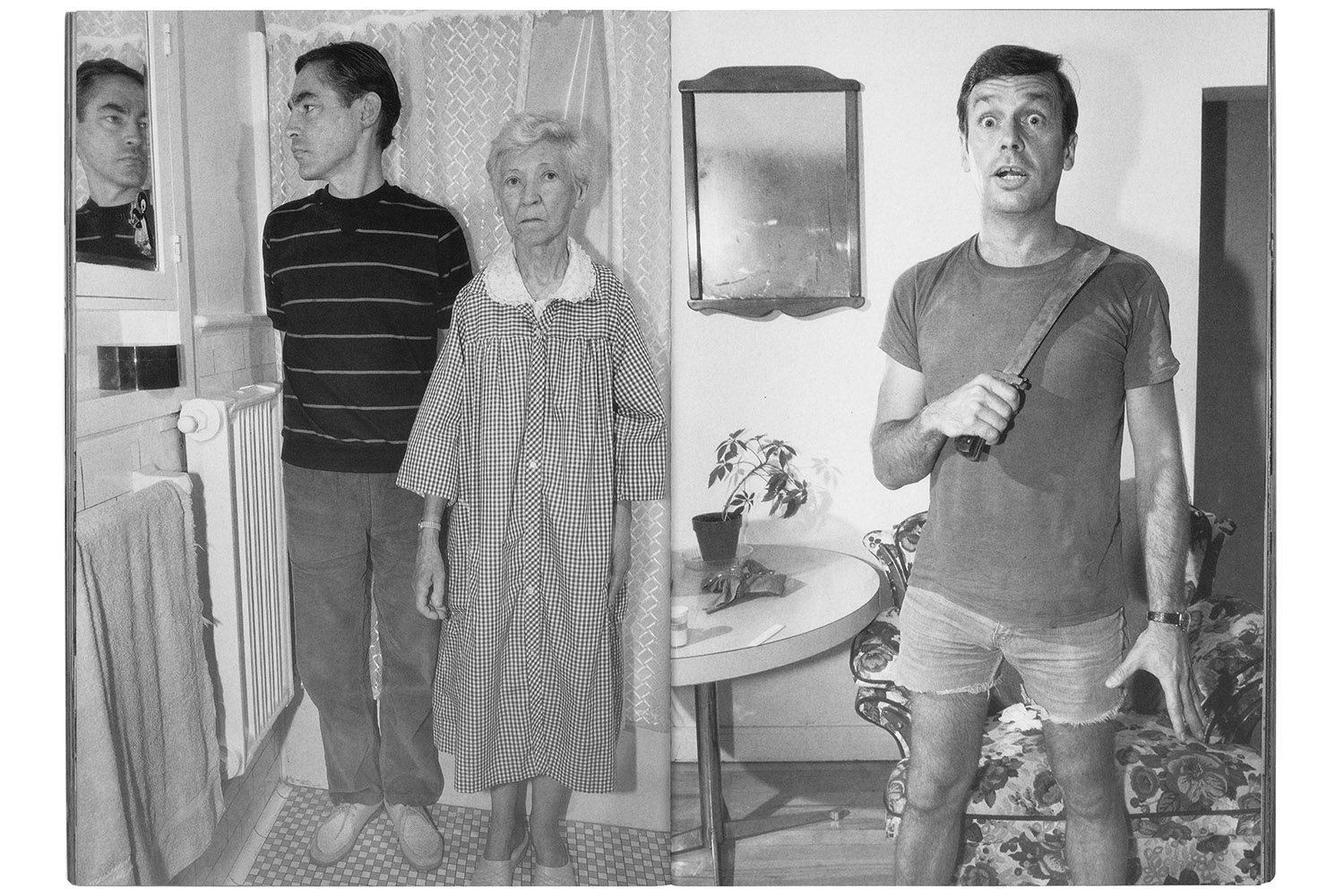

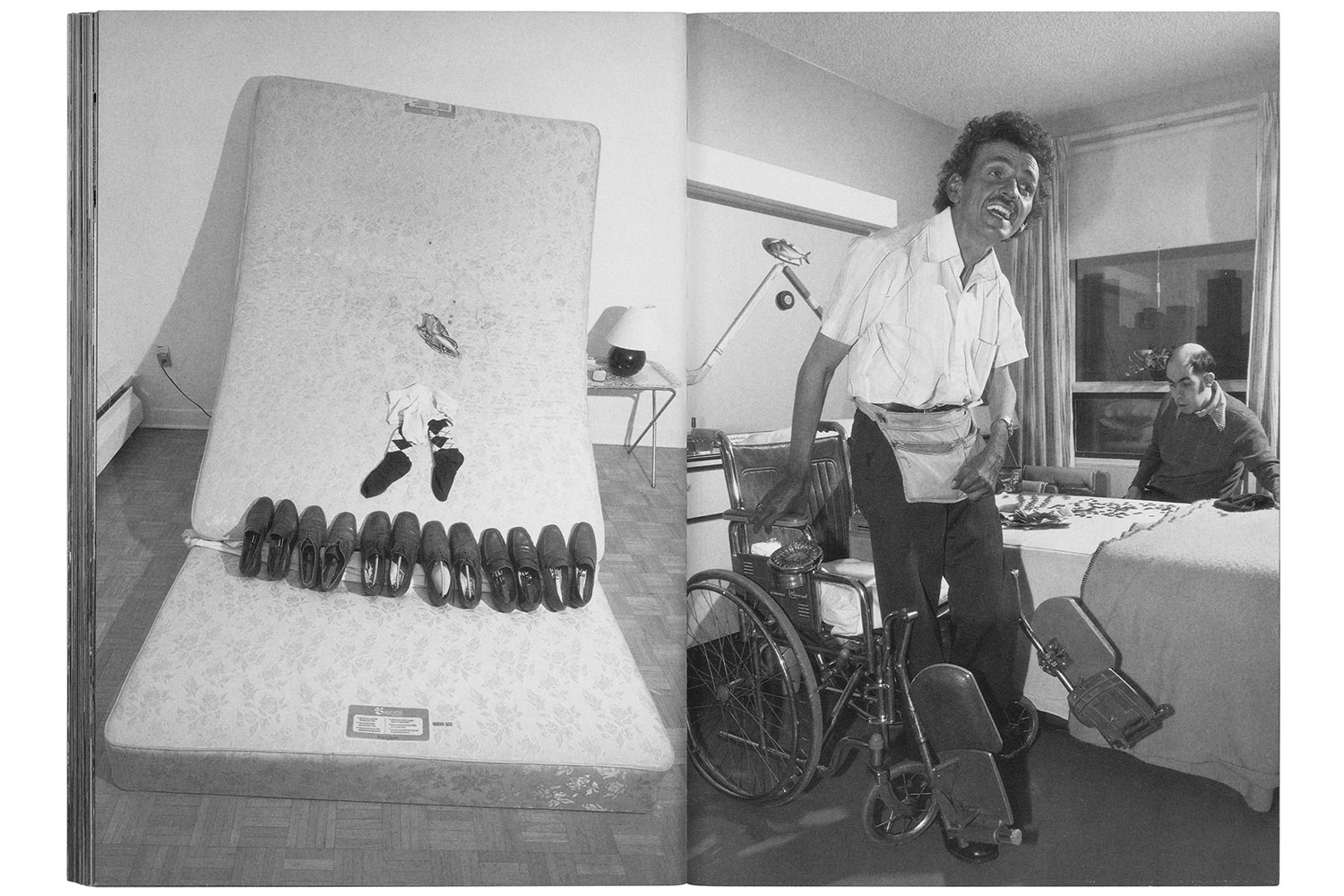

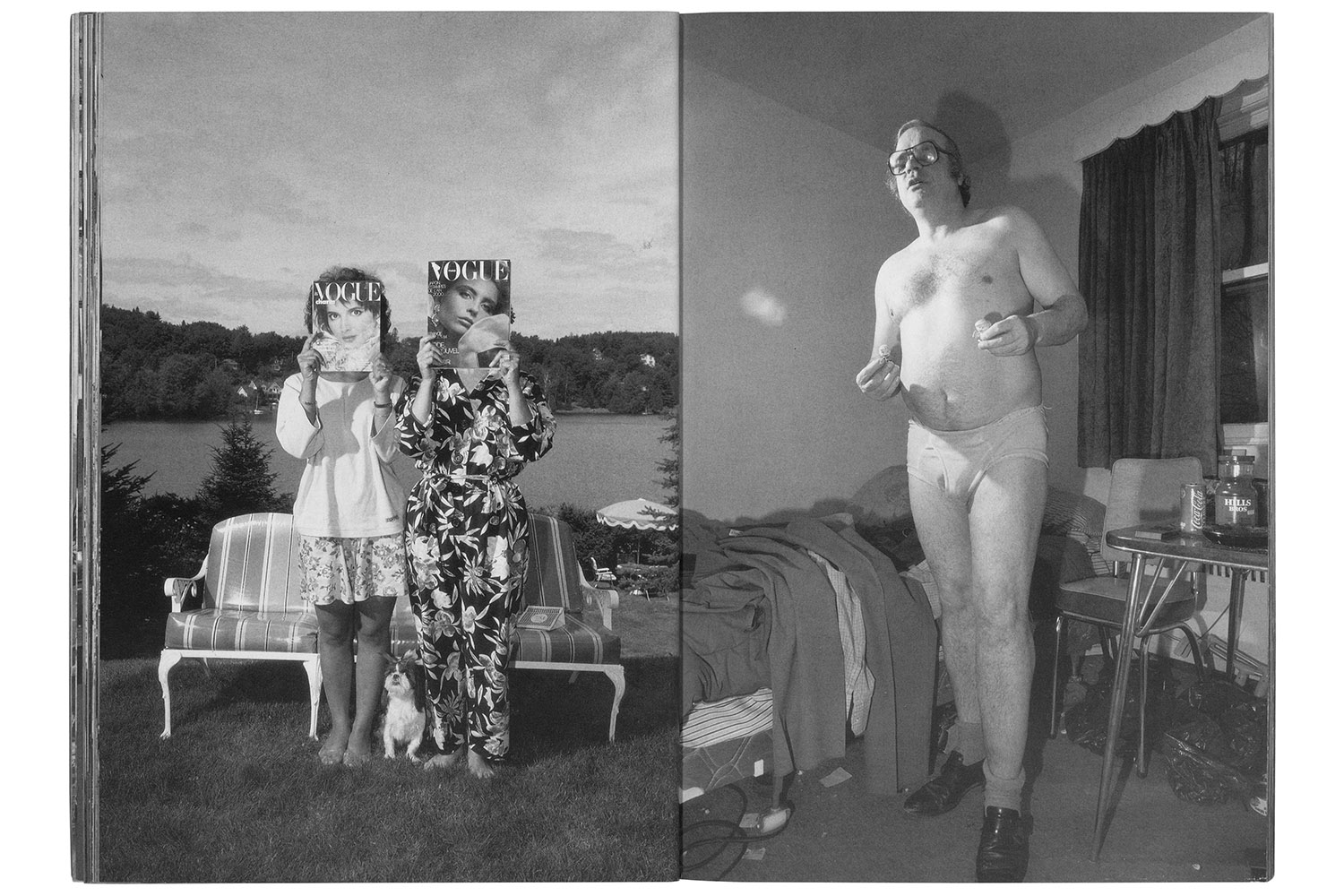

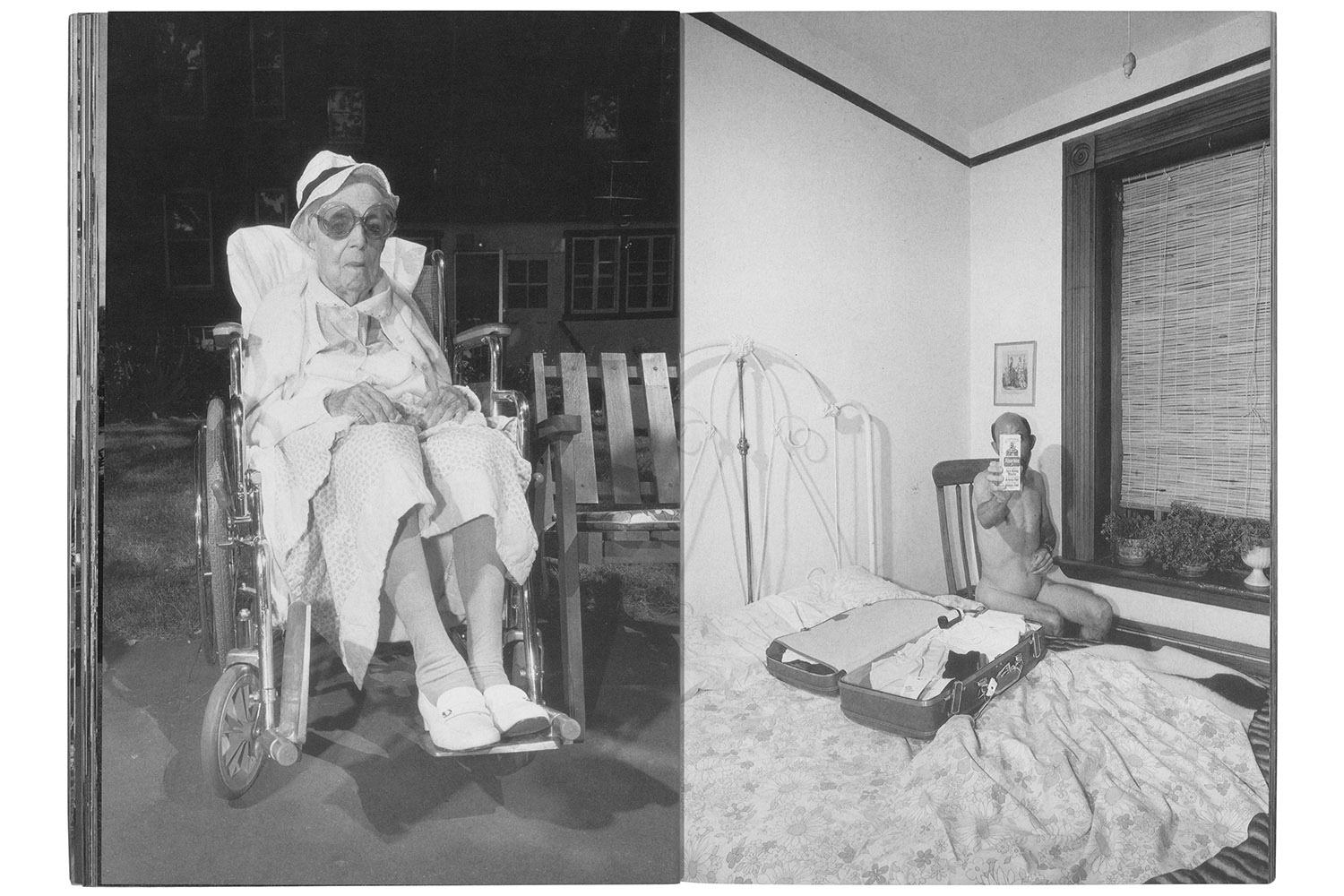

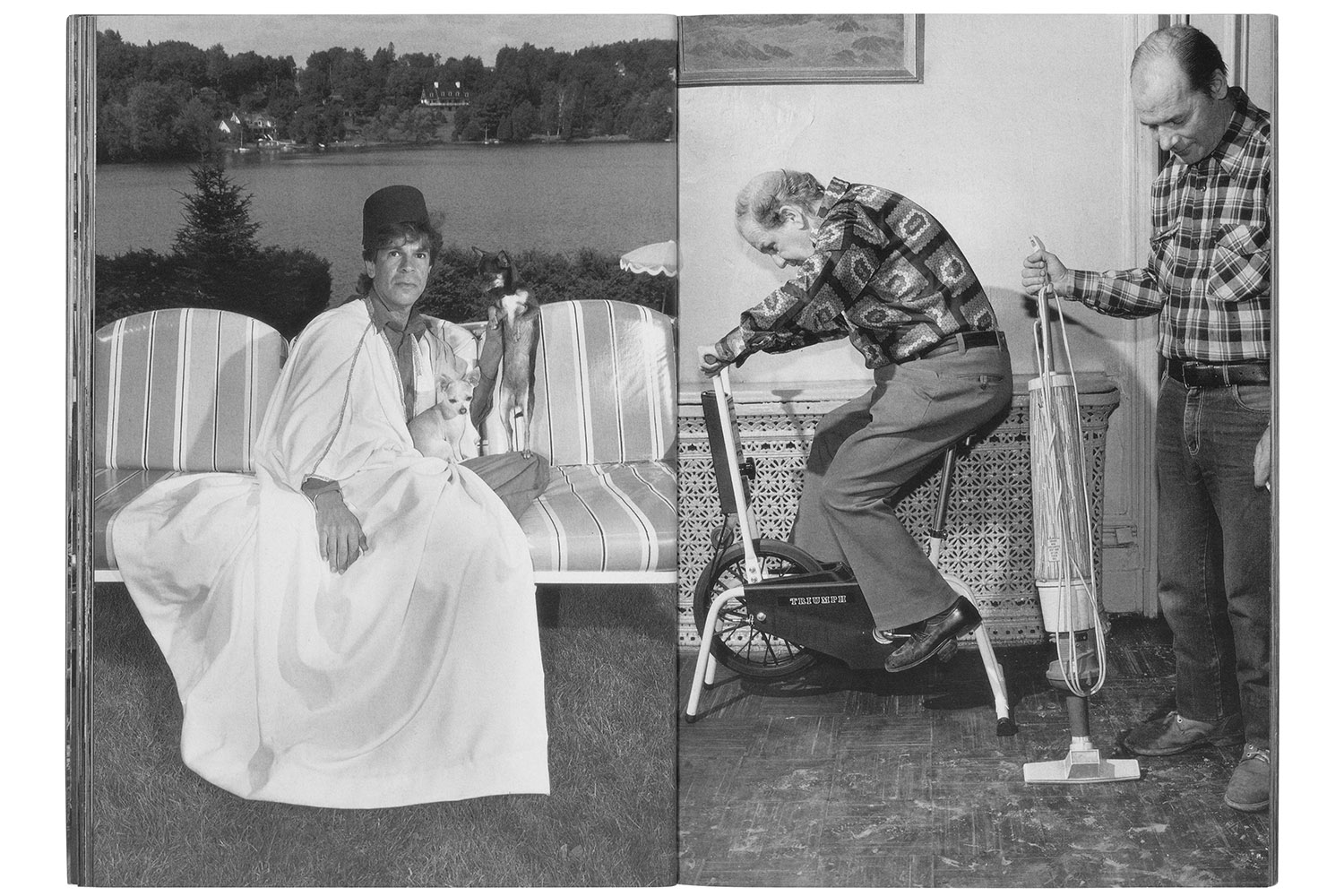

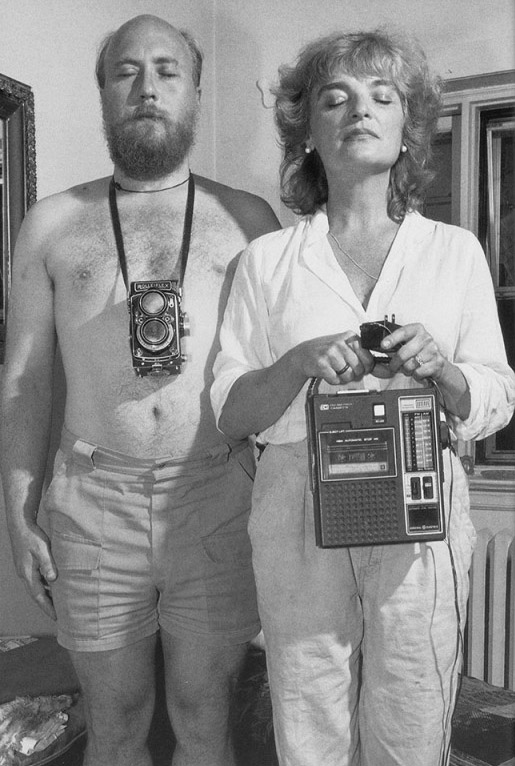

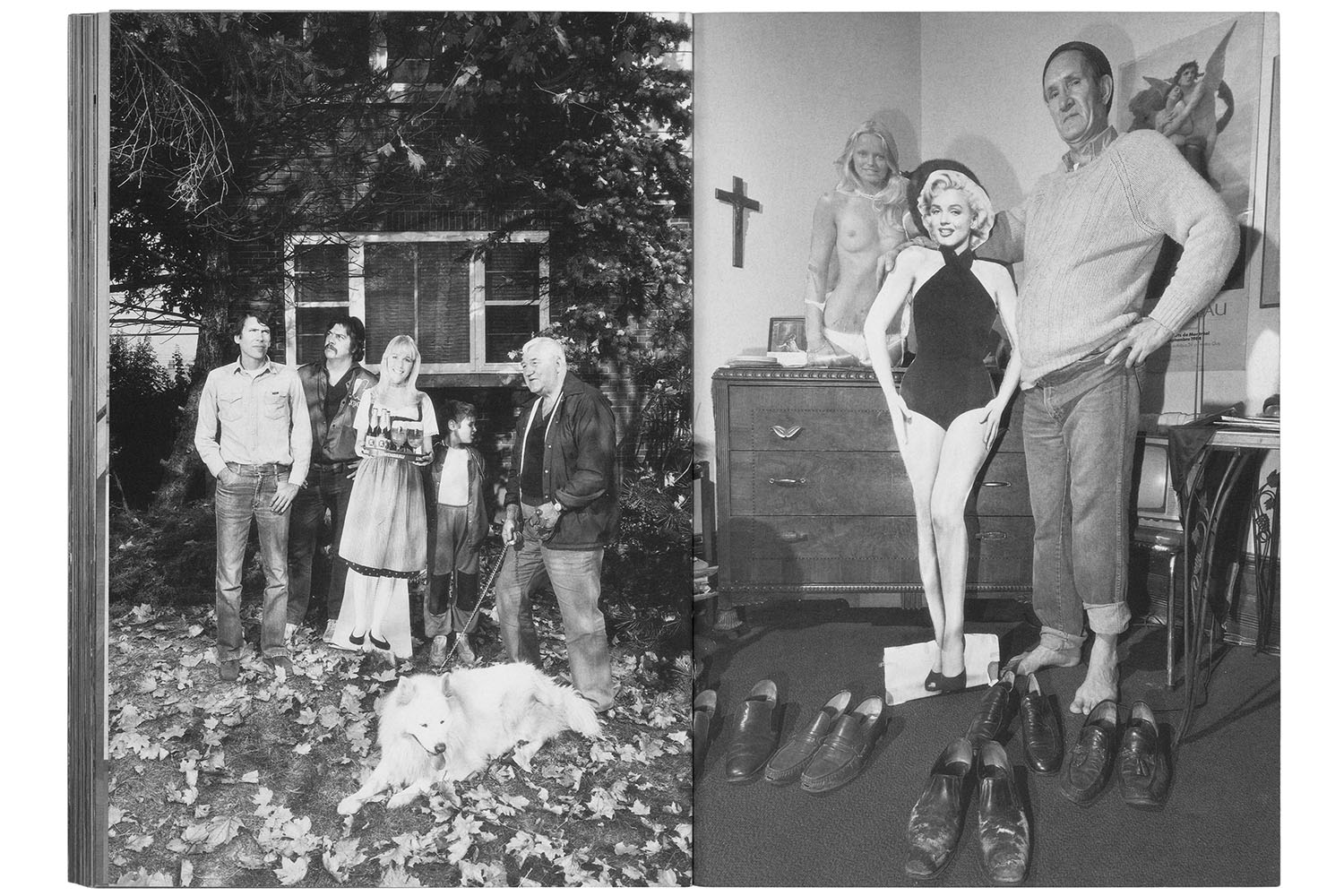

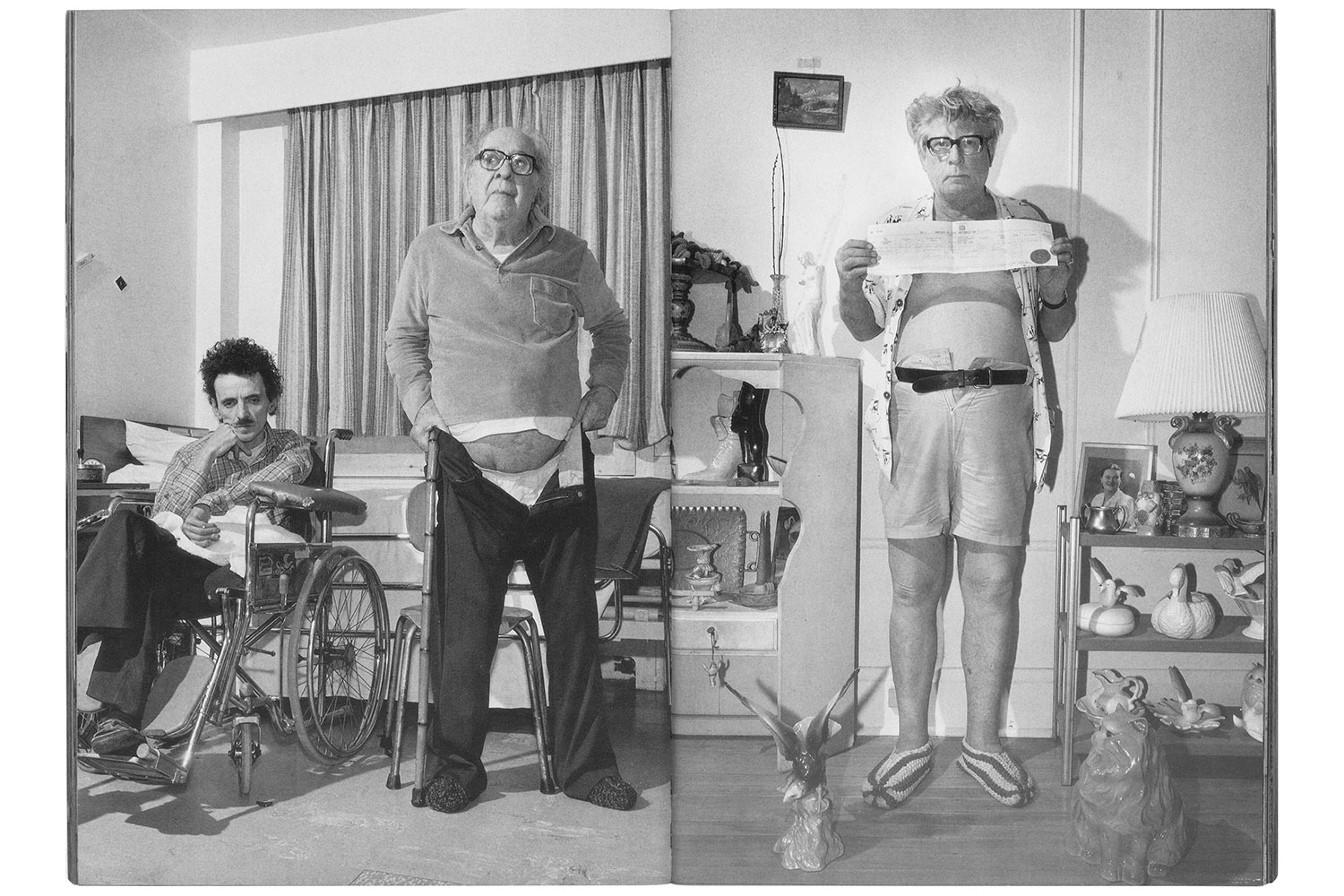

What is going on in these pictures? Is this an unsanitized view of society’s margins — the aging, the sick, the poor, the painfully awkward? Or is this a grotesque fantasy of a photographer-exploiter who pokes fun at other people’s misery? The photographs are incongruous and illogical; something about them is just not right.

The handful of spreads comes from Donigan Cumming’s infamous and rare 1991 photobook, The Stage (Maquam Press). Published in an edition of 600, the work went largely unrecognized until its inclusion years later in Gerry Badger and Martin Parr’s The Photobook: A History, Vol. 2 (Phaidon 2006). The Stage featured 250 jarring, full-bleed photographs across 125 pages — uncaptioned, unnumbered and undated. Though the imagery may have quoted the styles of social documentarians like Diane Arbus, Weegee and the lesser-known Chauncey Hare, the book was a first.

“I was stunned and could not recall seeing another like it,” says Jeffrey Ladd, a founder of Errata Editions, who are releasing Books on Books #19, a study of Cumming’s provocative monograph this spring. “It is a difficult work, often funny, and I found much of it offensive. I think it should be known in wider circles.”

Cumming’s art is meant to be challenging. “I want to be vexed, pushed, startled by a book,” he told TIME. “It shouldn’t be set up as too smooth a ride.”

Over the years, Cumming (66), who was born in Virginia and moved to Canada in 1970 in resistance to the Vietnam War had developed a rather jaundiced attitude toward photojournalism and other “straight” image-making.

“There’s a mythology of concerned photography that revolves around improving things for humans, stopping war and doing all kinds of things that are G-O-O-D,” he says, literally spelling out the word. “At the same time, the people that make this are usually driven by another set of motives, and some of them are not very transparent, and pretty self-absorbed.”

He decided he would adopt the documentary mode in order to expose its fracture points.

Cumming walked the streets and suburbs of Montreal, approaching people he thought looked interesting. He would offer them a picture of their apartment or their pet, and in exchange ask that they pose for one of his own. Motivated by a mixture of curiosity and desire, many agreed.

In their homes, surrounded by their possessions, Cumming directed his subjects into exaggerated, unreadable gestures while highlighting his own presence and the manipulation inherent to all photography with a heavy-handed head-on flash.

He sequenced the work from a distance of 15 feet — the length at which one might stand to view a large abstract expressionist canvas — arranging the pictures on a grid purely based on tonal quality, further disrupting narrative logic.

Cumming says he sought a truth about people by “confronting them as aggressively as possible and pushing them around, tricking them into revealing the secrets of their culture.”

“People act themselves all the time,” he says, “but it is not a theater that is false. It is a theater that leads to insight and a provisional truth.”

Though some were surprised, nearly none of his subjects objected when he asked for permission to release the work. They were comfortable with their roles, as Cumming was with his.

Indeed, he was fine playing aggressive, mean and cold-hearted — which is exactly how many view the photographer when they first encounter his work. Our own pained amusement at this compendium of wrinkles, sagging skin, awkward postures, gap-toothed grins and drool might make us feel complicit in the exploit. Instead, most blame the messenger.

Cumming hopes viewers get past that initial response. “If you leave unsettled and afterwards don’t look at photographs the same way, the next time perhaps you won’t approach them with the same shallowness,” he says. “That’s what’s important.”

Donigan Cumming is a Montreal-based visual artist who uses photography, video, painting, drawing, sound and text in experimental documentary films and multi-media installations.

Eugene Reznik is a Brooklyn-based writer, editor and photographer. Follow him on Twitter @eugene_reznik.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com