Having walked up and down a rather non-descript street on the outskirts of central Barcelona, looking and looking again for the address I’d been given, I sat down on what had once been a small loading dock of a nineteenth-century warehouse – now apparently subdivided into sparse offices, artist studios, and loft apartments – and pulled my phone from my pocket.

It was mid-afternoon, siesta-time, and every one of the surrounding shop-fronts had their corrugated steel shutters firmly pulled down; the neighborhood felt temporarily abandoned, as if all activity had been peacefully swept away by the sweltering Spanish sun. Yet for me, the heat and virtual silence were only exacerbating my frustration. I was now late for my appointment.

I carefully re-read the email that I was sent earlier in the week, describing a thin black-iron gate with a small grey buzzer to the left. Squinting, I panned up and down the opposite side of the street, scrutinizing every threshold and doorway, when suddenly the faint squeak of metal hinges sang out about half a block to my right. A thin gate – presumably once black, but now entirely covered in illegible white graffiti – opened up, and a friendly, bearded face peered out. I’d finally found him (or rather, he’d found me): Joan Fontcuberta.

He waved me over, and as I approached, I noticed that he was wearing what appeared to be a pair of steampunk-like goggles, made out of two large, brass, Victorian photographic lenses. He quickly explained that they worked a bit like Google Glass, but rather than feeding him current information derived from the internet, they instead transformed everything he saw into a sepia-toned simulation of how it would have looked one hundred and fifty years ago; the streets around us were bustling with factory workers, horse-drawn carriages, and scruffy working-class children running to and fro, at least to his eyes.

He turned, and as I followed him through a small courtyard, he quickly pointed out a bulbous Honduran cactus growing in one corner, of which he seemed immensely proud, telling me that it was a specimen of Parodia magnifica – a gift from a friend, the horticultural geneticist Horacio Méndez – and that it was a minor miracle that it had managed to survive in Barcelona’s rather dry climate, thanks to his tender care. After climbing several narrow flights of stairs, we then came to a bright white room that appeared to be a photographic studio.

But Fontcuberta explained, it was in fact, in photographic terms, quite literally a “dark room”; several years back when the Iron Curtain fell, he had managed to secure several barrels of paint (through a contact who had worked for one of the Soviet space programme’s top-secret research labs) that, despite its brilliant white appearance to the naked eye, actually absorbed any light that passed through a glass lens – so that any photograph taken in this room would appear entirely unexposed.

Immediately, I pulled my phone from my pocket again, clicked on the camera app, and attempted to take a picture of Fontcuberta as he removed his goggles; but sure enough, all that was recorded was a rectangle of pure, pitch-black darkness. With a mischievous I-told-you-so smile, he finally led me into an office – lined with dusty leather-bound books, botanical illustrations, a collection of high-powered telescopes, and display cases filled with the fossilized remnants of what he claimed were “monsters and mermaids” – and invited me to begin the interview.

“I do not believe in documentary approaches,” Fontcuberta recently stated in the film made by the Hasselblad Foundation, which accompanied the announcement that he was the recipient of their 2013 International Award in Photography. “Reality does not exist by itself. It’s an intellectual construction; and photography is a tool to negotiate our idea of reality.” For more than thirty years, Fontcuberta has been challenging the veracity of the photographic medium – as well as what Lewis Hine once called society’s “unbounded faith in the integrity of the photograph” – by constructing elaborate documentary-like dossiers that on their surface appear convincing, but upon closer inspection reveal themselves to be satirical and at times rather absurdist fabrications, which cleverly pastiche many of ways in which photography is used to evidence or substantiate a particular reality.

“It’s of note that I was born under Franco’s dictatorship, and thus grew up in a totalitarian regime that manipulated the media to benefit its own legitimacy,” he remarks, “Later, I worked in both journalism and advertising, which also familiarized me with illusion and simulation.”

Although he is often defined as a conceptualist, Fontcuberta is as much a contextualist, whose projects adopt and borrow from the authoritative tones, languages, contexts and constructions that are used to legitimize photographic materials (and vice versa) – archival materials, scientific jargon, journalistic articles, academic texts, and so on – in order to subvert them.

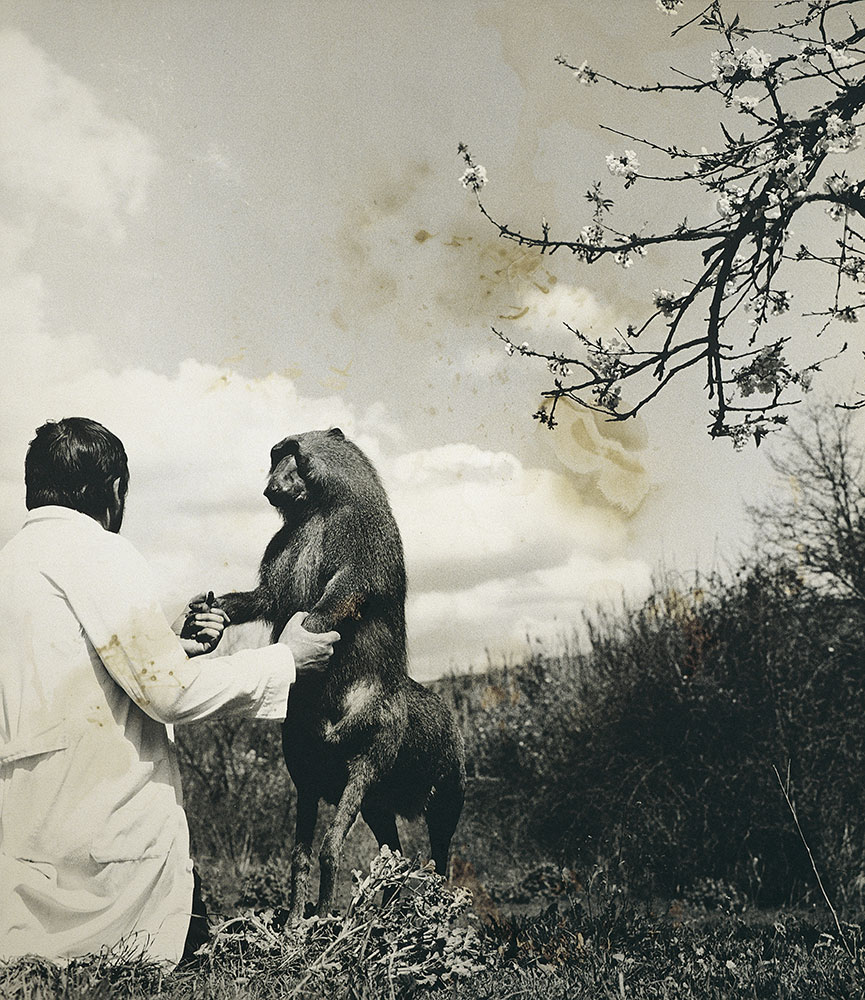

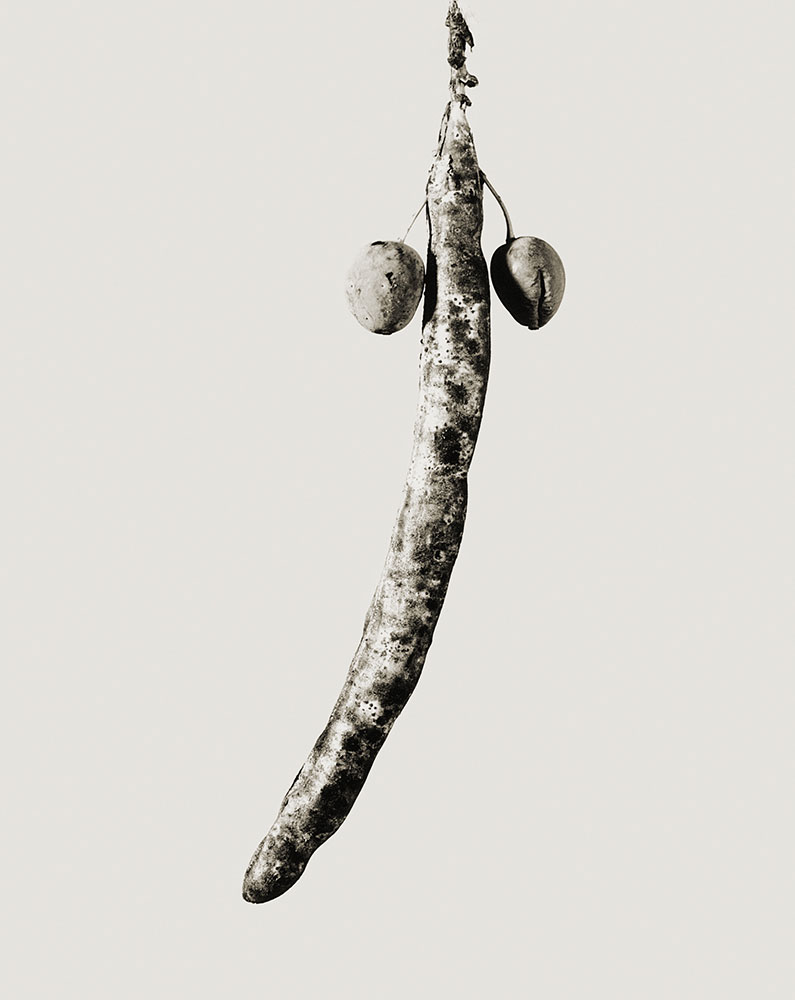

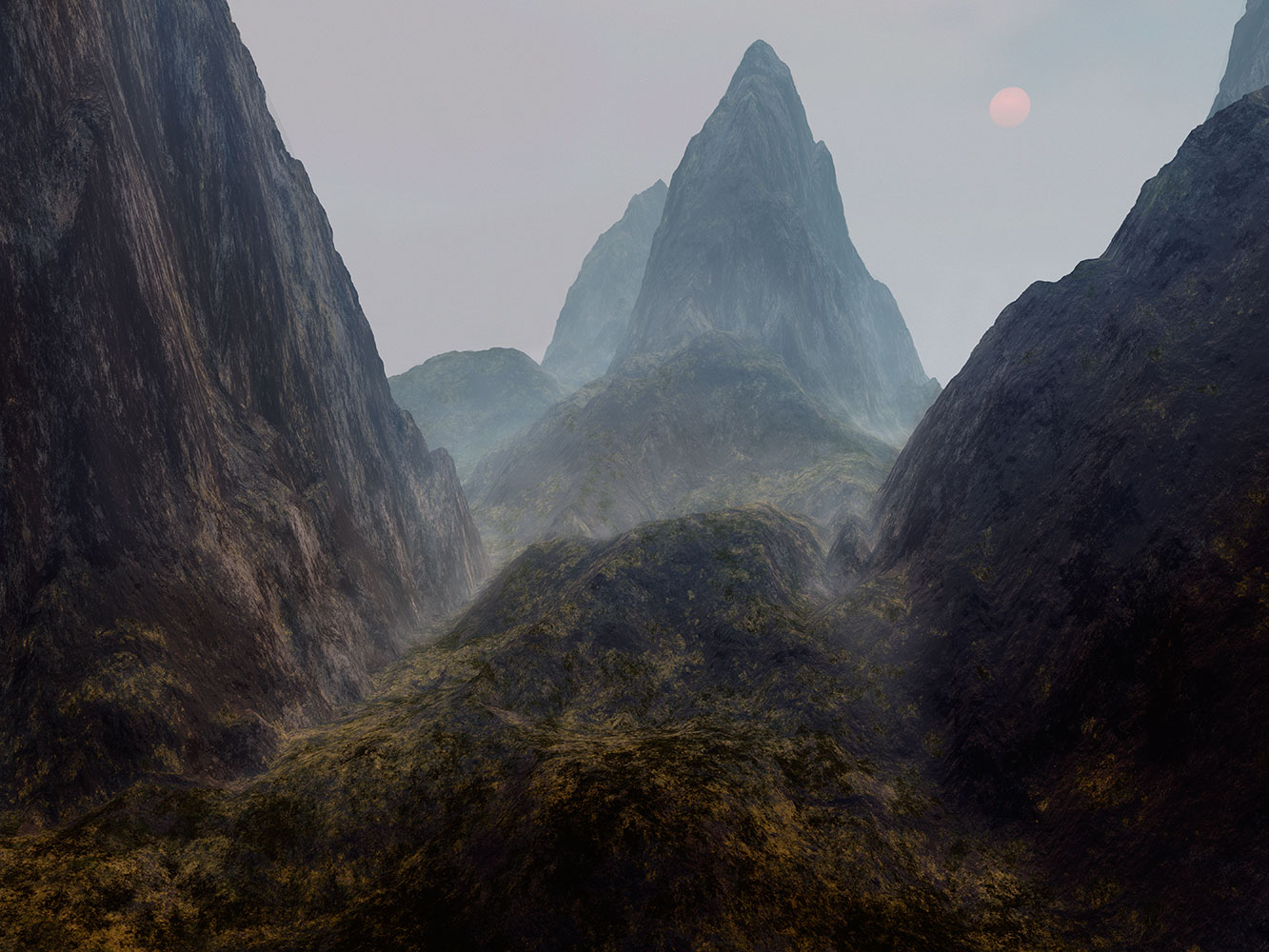

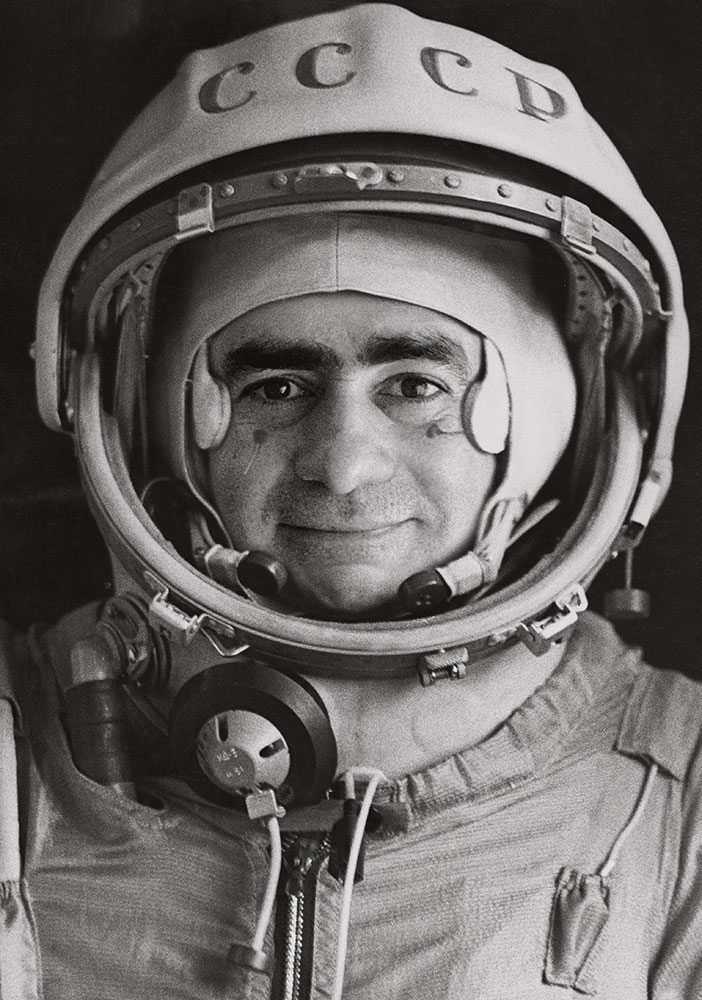

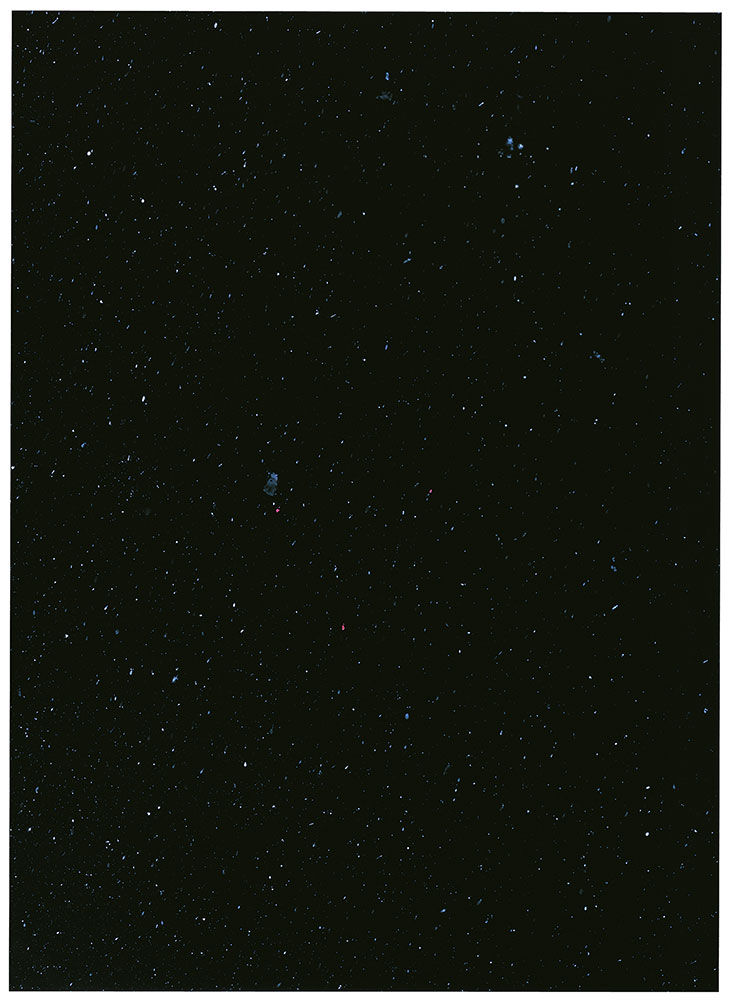

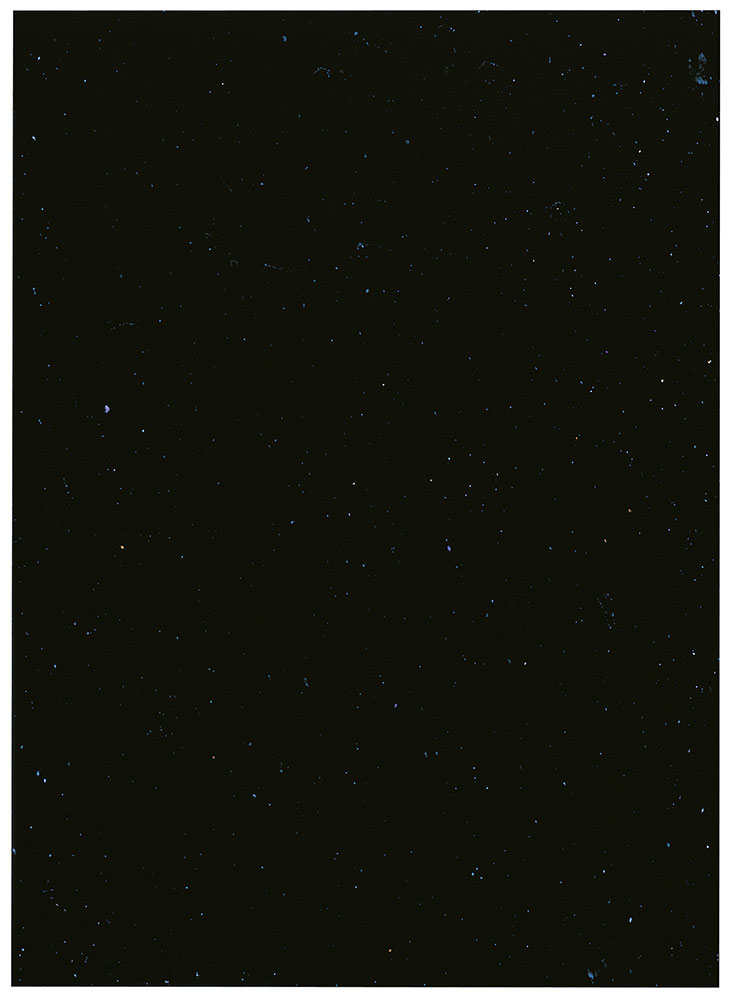

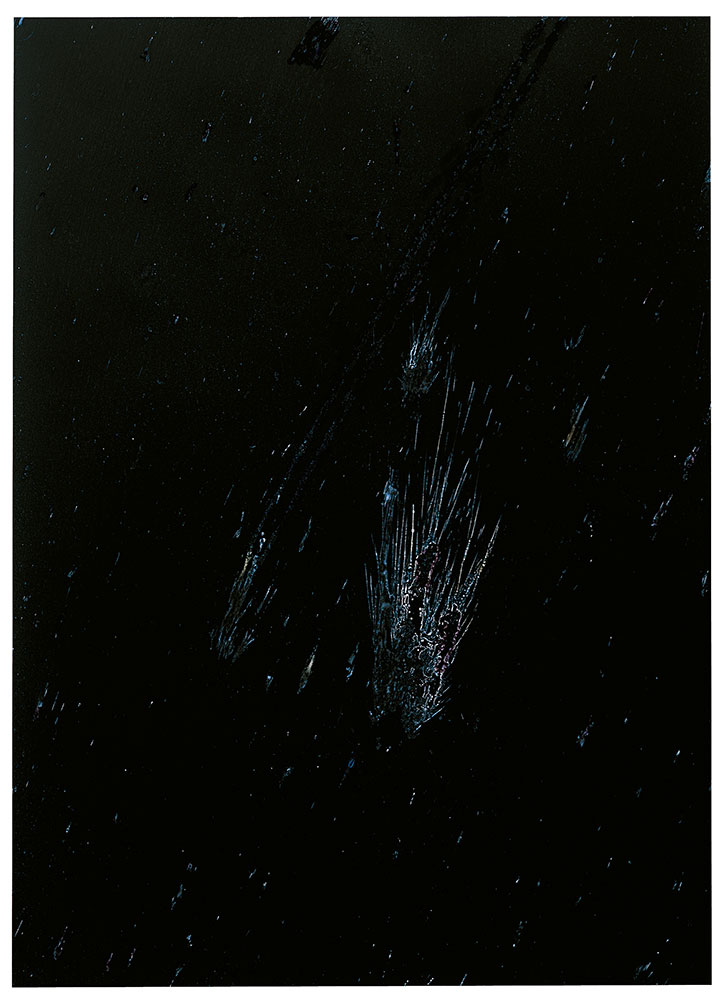

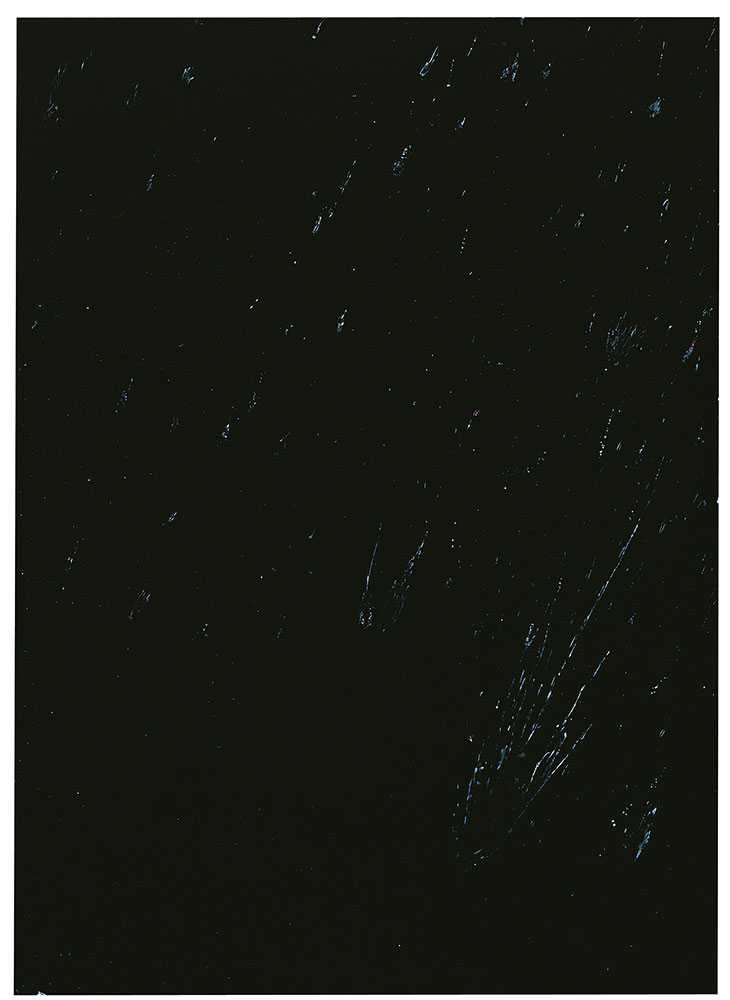

In conjunction with the Hasselblad Award, the most iconic of these projects, including Herbarium (1984), Fauna (1987), Constellations (1993), Sputnik (1997), Sirens (2000) and Orogenesis (2002), have recently been collected together and republished as The Photography of Nature & The Nature of Photography, a luxuriously printed and beautifully designed monograph published by MACK late last year. “The question is: which is the right room for photography?”, Foncuberta asks. “Photography can live different lives according different homes….[T]he important thing today is no longer the fabrication of the image, but the capacity to project meaning onto it.”

In the same 1909 speech quoted above, Lewis Hine warned, “[W]hile photographs may not lie, liars may photograph.” Paradoxically, by wholeheartedly embracing the role of the “liar” and undermining the role of photography as form of objective fact, Foncuberta reveals that the medium is actually capable of revealing truths much deeper than simple facts, specifically in relation to how we define, interpret, negotiate, and understand reality today.

“We can consider the history of photography to be a dialectic process between the image as description and the image as invention – that is to say, between documentation and fiction,” he argues, “But today we cannot accept these poles as mutually exclusive concepts, because one impregnates the other…Reality is nourished by fiction in the way that fiction is a narrative essentialized out of an inherent need to understand reality. Thus the first and more important truth photography conveys, is its own ambiguity: the fact that we need to interpret it.”

Although his images are ultimately as fantastical as the story of our meeting told earlier (in truth, our interview was conducted entirely via email; I’ve never visited Fontcuberta’s studio, or even met him face-to-face) they serve as an important lesson in how this ambiguous territory, between fact and fiction, is incredibly ripe with both potential and meaning. “The problem of photography is not that it embodies truth,” the eccentric, polymathic scholar proposes across from the dreamed-up desk of my imaginings, “but too much truth; it’s a question of excess.”

Joan Fontcuberta is a Catalan photographer, artist, writer and educator.

Aaron Schuman is a photographer, writer, curator and the editor of SeeSaw Magazine.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- 11 New Books to Read in February

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

- Introducing the 2025 Closers

Contact us at letters@time.com