When the pioneers of photography came to describe their new invention, they faced a basic problem: no one had ever seen such a thing or knew what it was good for. The names they gave the new medium tended to reflect their different senses of its salient features: heliography, calotypy, photogenic drawing and sun pictures, to name a few. And the shifting standards they applied to finished pictures revealed an even more basic ambiguity. Should they be accurate or expressive? Documentary or artistic? Was photography mechanical or imaginative, science or art? Or both at once?

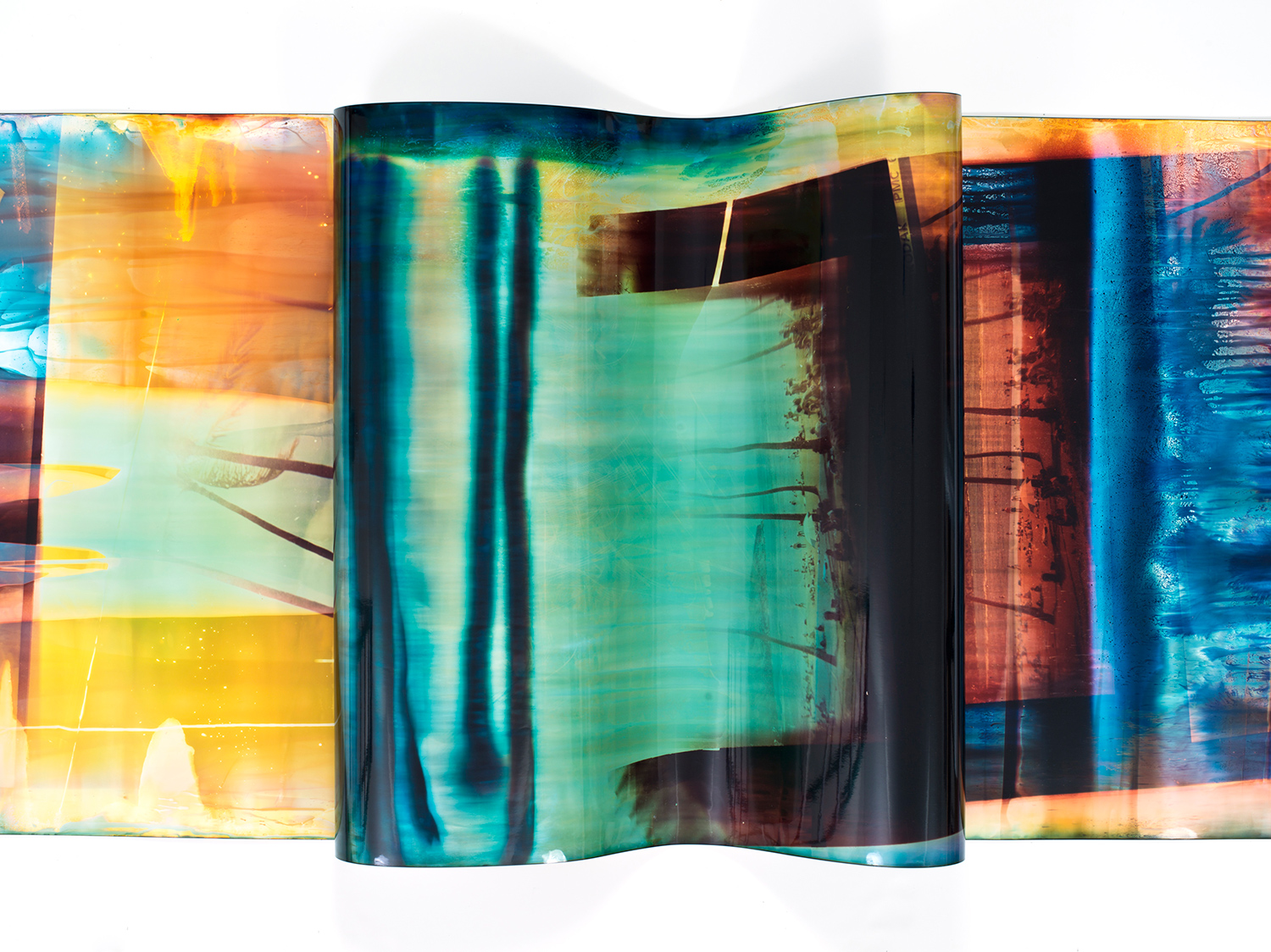

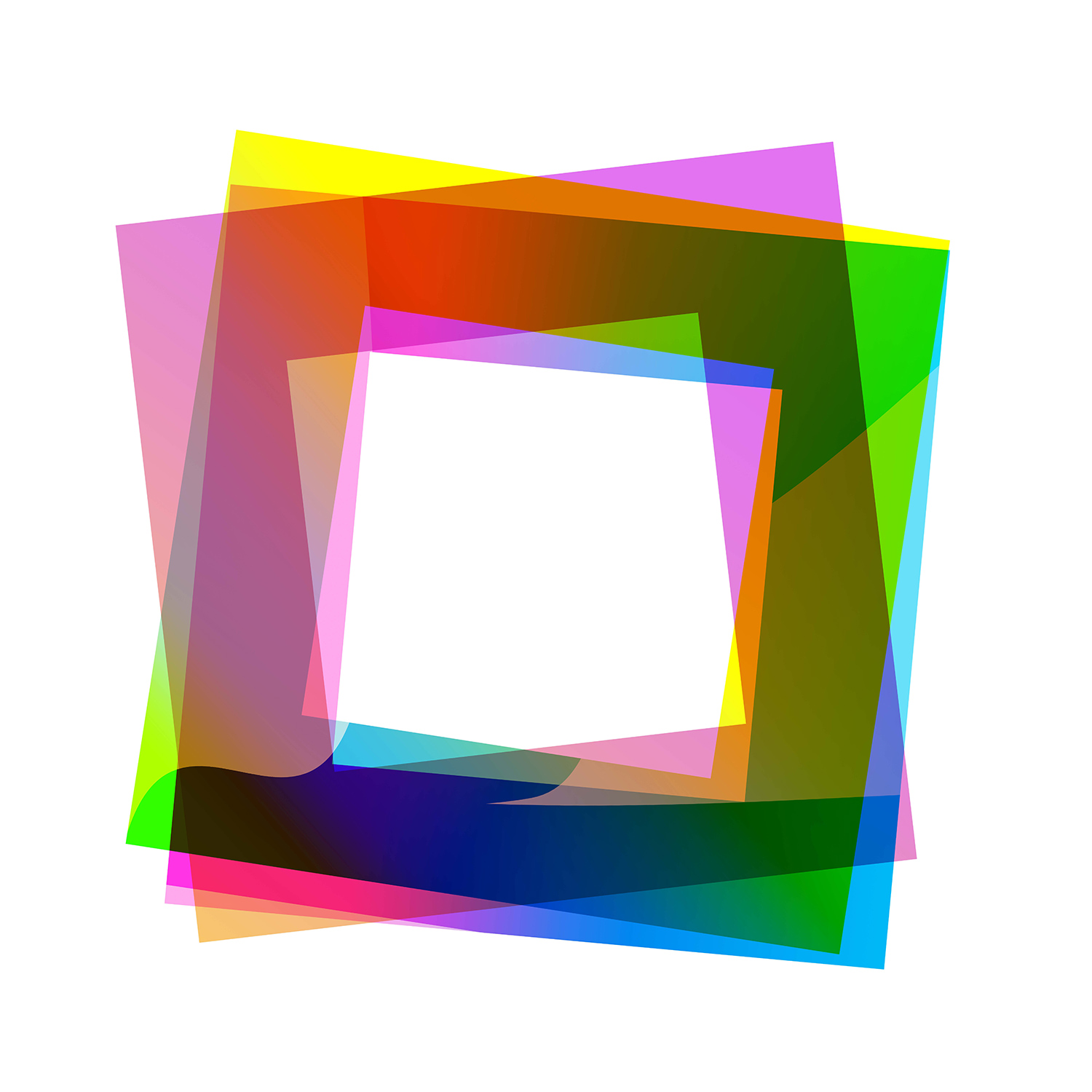

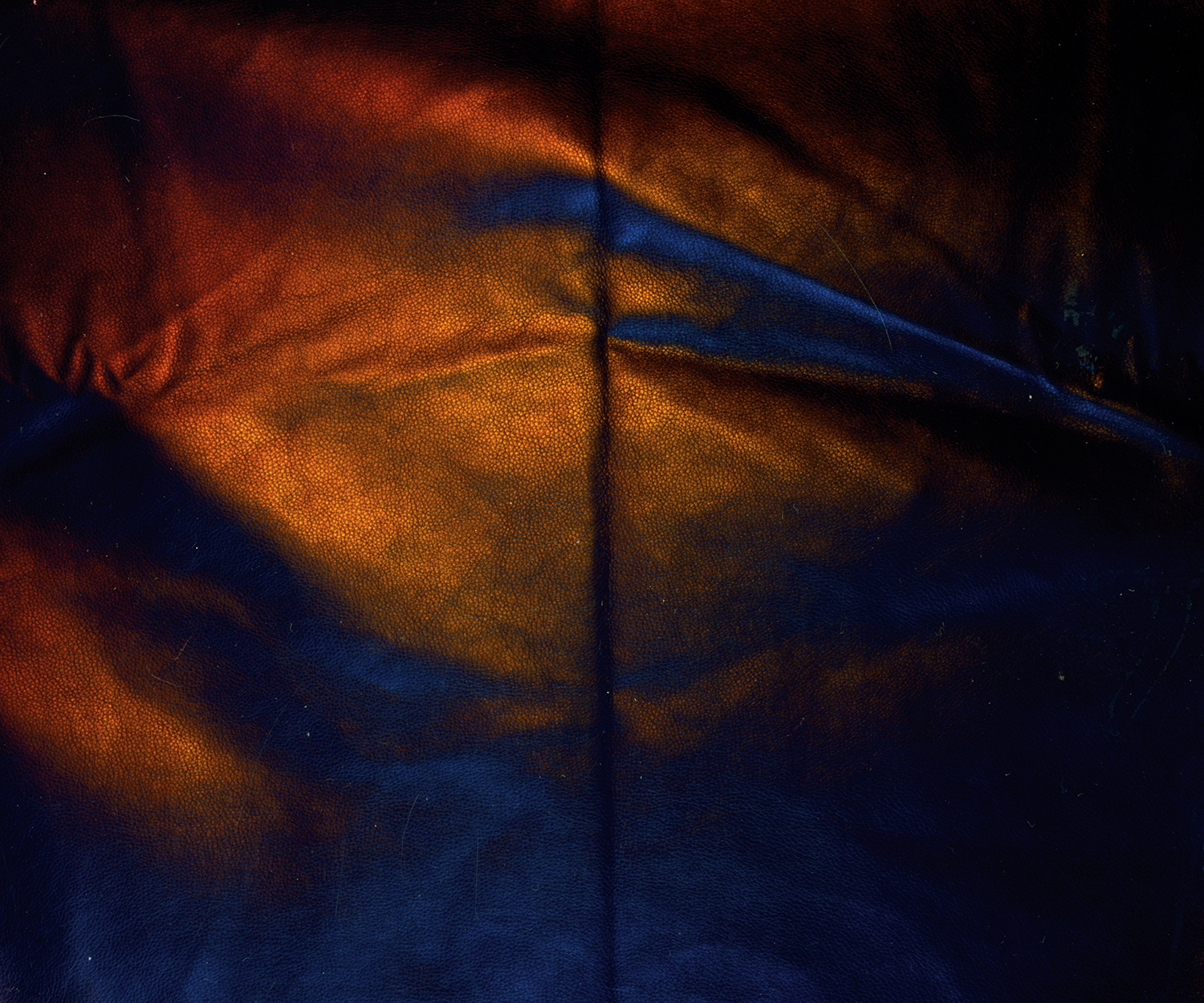

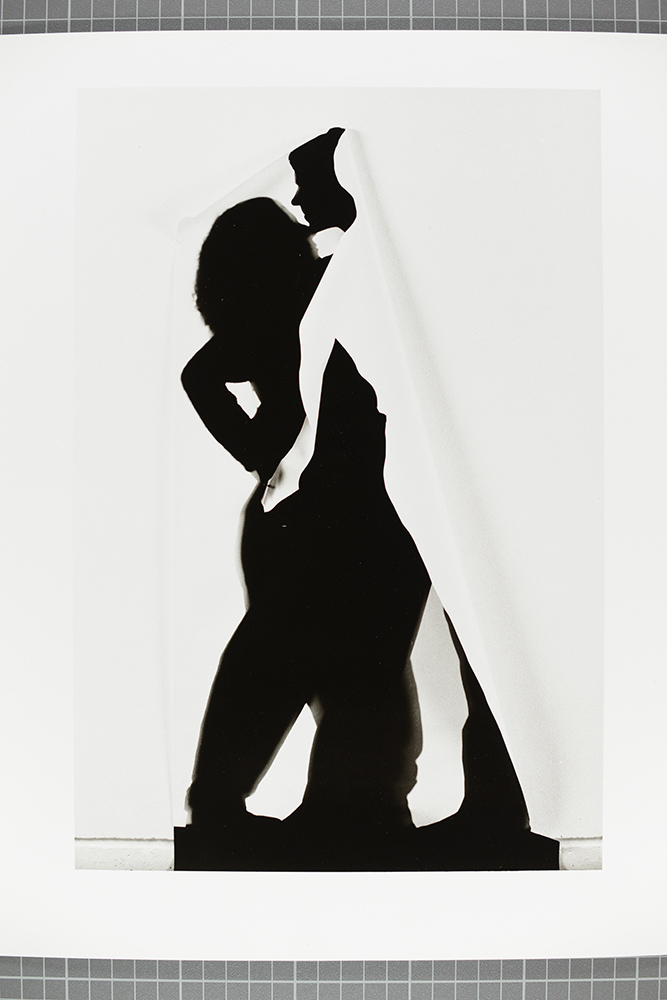

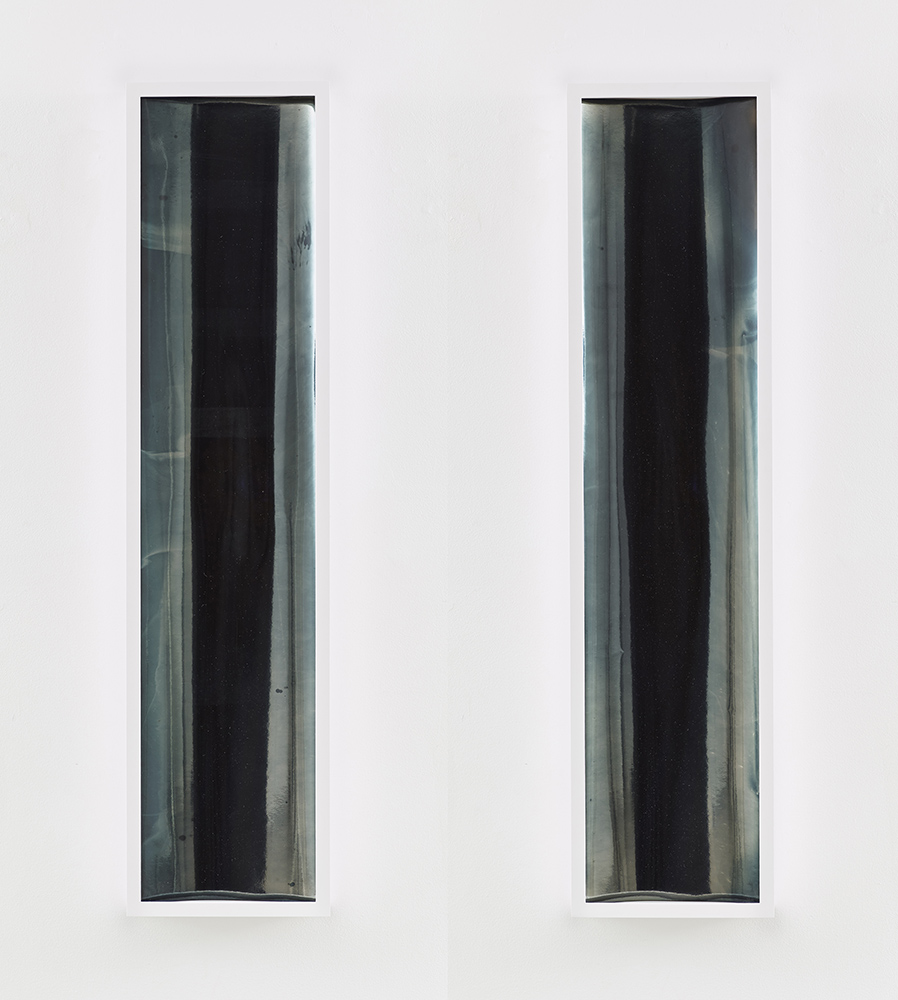

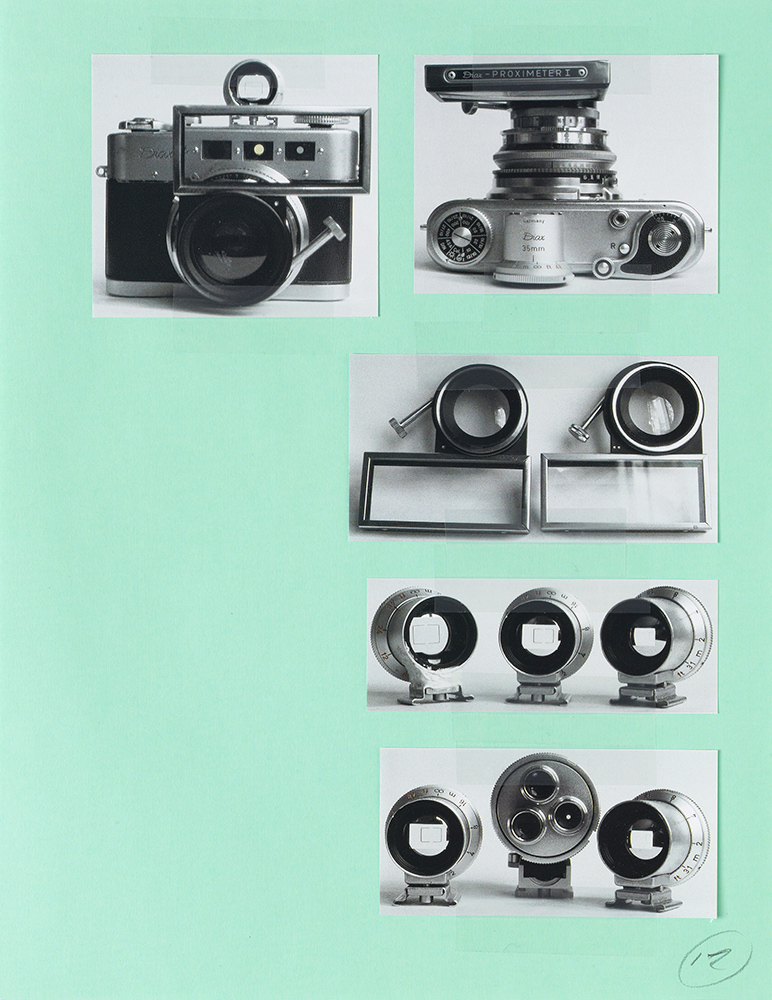

Fast forward 150 years and we find all of those questions about the medium haven’t been settled, only revised and expanded. They’re also the focus of a new exhibition at the International Center of Photography in New York. Curated by Carol Squiers, What Is a Photograph? brings together 84 works by contemporary photographic artists (calling them photographers doesn’t seem quite right). Many of the pieces are abstract, and all of them are likely to challenge what most of us think of as a photograph. There are photos that border on sculpture (by Letha Wilson), photos that aren’t photos at all but just photo paper (by Marco Breuer and Alison Rossiter), photos that look simple but have elaborate back-stories (by Liz Deschenes and Christopher Williams ), and photos that look like something went terribly wrong (by James Welling, Matthew Brandt and Eileen Quinlan). Visitors to the exhibition had better be ready to read wall text or buttonhole a staff member because these pictures need their captions: most of them can’t be parsed without some sort of explanation.

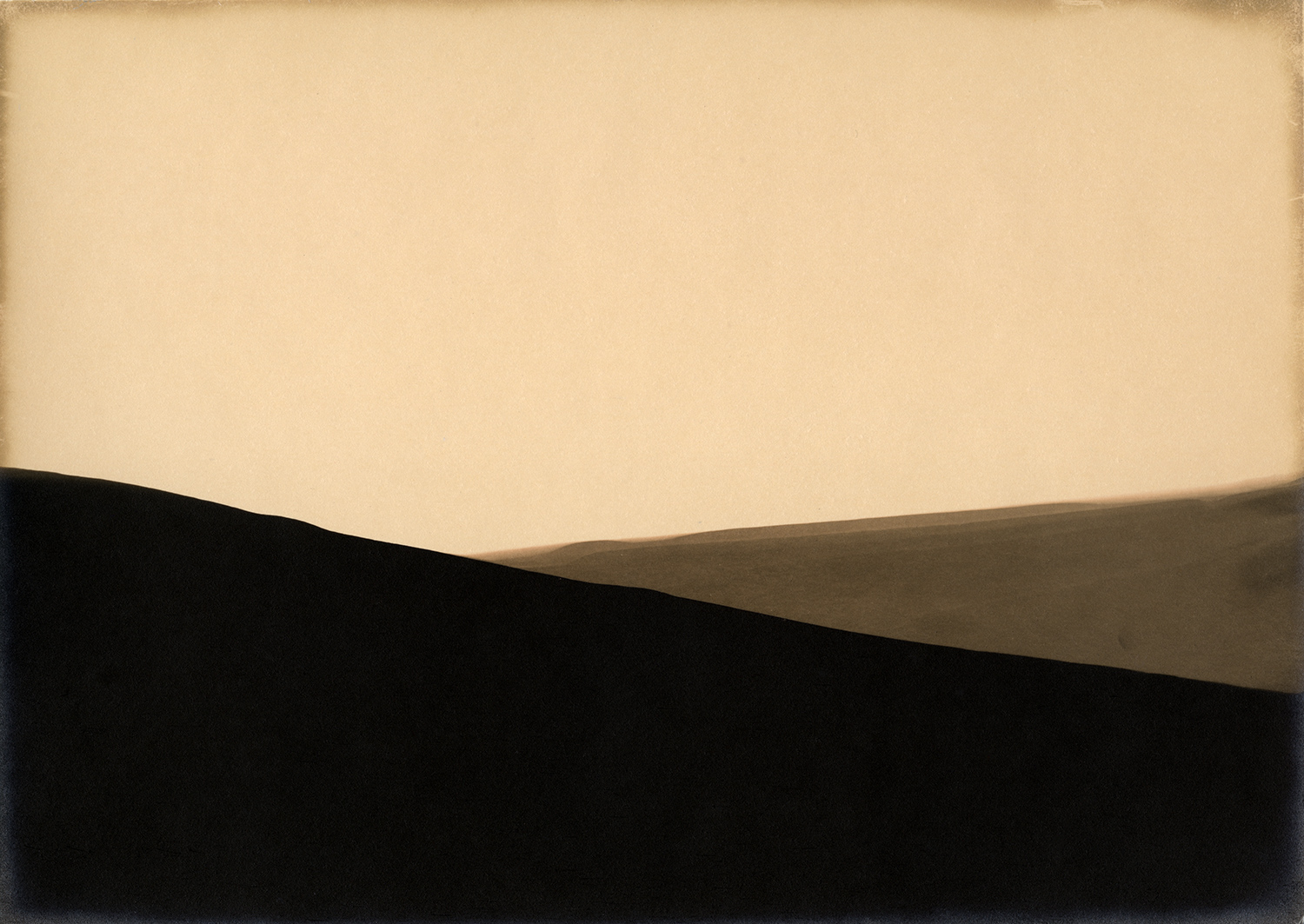

How did we get here? How did art photography go from, say, an Ansel Adams landscape to pieces of distressed paper with no referential images at all? The exhibition itself provides little explanation since it is focused on what’s happening now. But throughout the history of photography there have always been dissenters from the prevailing consensus about what a photograph is supposed to be and do. The show’s catalog includes essays by Squires and photo historians Geoffrey Batchen and George Baker that fill in some but not nearly all of the blanks. The exhibition’s only gesture to the past is the inclusion of work by German Sigmar Polke and Polaroids by photo-provocateur and self-portraitist Lucas Samaras. They are included not just because, like so many of these artists, they play with photographic processes but also because they bracket the period of Squires’ interest. Her thesis is that something happened to photography in the 1960s and ’70s that made it impossible to look at art photographs – or any photographs, for that matter – in the same old way.

That something was conceptual art, the movement that saw art as primarily a way of exploring ideas. Although it often yielded nothing more than ephemeral events or experiments, its impact is all over the art world and this exhibition. Conceptual art, after all, introduced to the art world various types of photography that had been excluded or ignored, while calling attention to the fact that even photographs that seemed straightforward often demanded a second look — because nothing about making a picture using a machine and chemicals could be considered “natural.” These ideas dovetailed with the simultaneous revolution of Pop art, especially its embrace of kitschy stereotypical imagery from the (photo-based) mass media.

The cumulative effect of this upheaval was to shift the focus from the traditional decisions photographers make in order to control what happens in the frame to all the issues and questions that lie outside the frame: the photograph’s “construction,” distribution, display and audience response. Since then, the important question has become not “What is a photograph?” but what is a photograph for? Additional questions, like who’s doing the looking, how do audiences make meaning, and what are their desires and assumptions, are wrapped up in that central query.

Visitors to the show are likely to be surprised at the lack of emphasis on digital manipulation. After all, isn’t that what’s changing everything, by undermining photography’s “truth”? With the exception of Kate Steciw, who samples work from the Internet, most of the artists prefer to put digital technology in the back seat, and seldom address issues of veracity head on. That’s probably because they all begin with the assumption that photography never did simply open a window on the world; instead it created new worlds through the complex process of making images. From the very beginning, truth yielded to truthiness in the camera’s eye. And while we may still seek glimpses of reality in photographs, this exhibition demonstrates that we are more and more likely to see multifaceted reflections of photography itself.

Lyle Rexer is a critic, curator and educator. He is the author of many books and articles on photography including The Edge of Vision: the Rise of Abstraction in Photography.

What is a Photograph? is on view at the International Center of Photography in New York City, Jan. 31 – May 4, 2013.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Cybersecurity Experts Are Sounding the Alarm on DOGE

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Michelle Zauner Stares Down the Darkness

Contact us at letters@time.com