A recent exhibition at the Deutsches Filmmuseum in Frankfurt, oriented around the work of writer, director and producer Rainer Werner Fassbinder, provided a unique opportunity to consider the still image isolated from its original context. Fassbinder, after all, is one of very few filmmakers who have established a visual vocabulary so distinctive that it might be identified by a single frame. Both a theatrical retrospective of Fassbinder’s work and a gallery exhibition, featuring primary materials from the Rainer Werner Fassbinder Foundation’s archives, Fassbinder NOW argues for the German iconoclast’s relevance to contemporary art, spotlighting kindred work by Tom Greens, Runa Islam, Maryam Jafri, Jesper Just, Jeroen de Rijke & Willem de Rooij, and Ming Wong.

As illustrated in Fassbinder NOW, the filmmaker’s singular sensibility was most keenly represented in the dozen or so melodramas he created between 1971 and 1975, movies like The Bitter Tears of Petra von Kant (1972) and Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), which portray alienated individuals whose love — beset by class distinctions, family tyranny, and corrupt institutions — often curdles inexorably to hatred.

During this period, Fassbinder was consciously modeling his work after that of the German-born Hollywood filmmaker Douglas Sirk, still highly celebrated today for his luscious, subversive melodramas like All That Heaven Allows (1955) and Written on the Wind (1956).

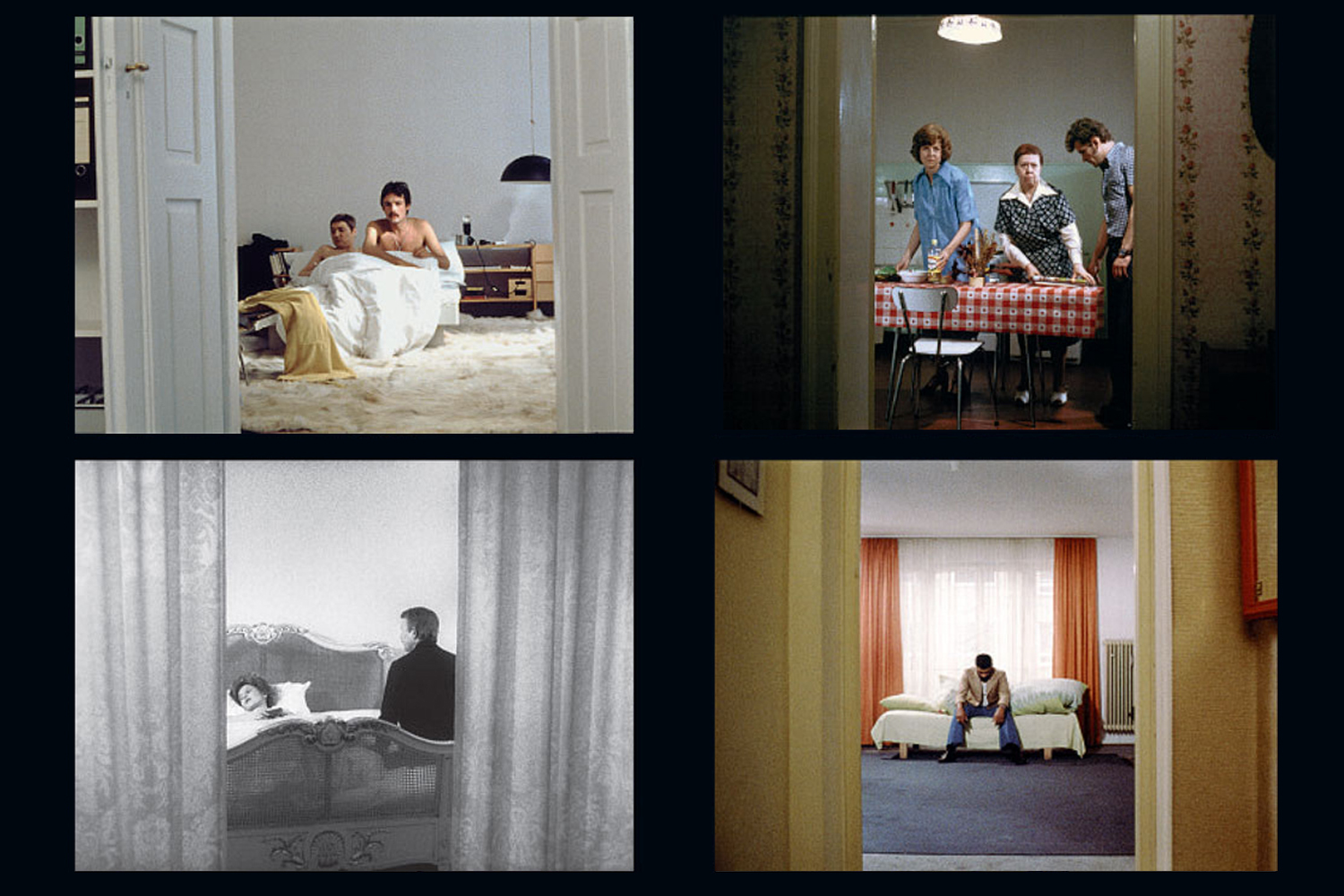

Though Fassbinder began his career writing and directing stage plays, his films always exhibited a highly considered photographic sensibility; after encountering Sirk, they underwent a baroque explosion of meticulous framing, mise en scene and color palettes. Characters are portrayed through doorways and domestic crannies; those who share common space are separated by window frames, semi-transparent fabrics, and home furnishings while their faces are fractured by multi-paneled mirrored surfaces.

The artwork in Fassbinder NOW, organized in collaboration with the Fassbinder Foundation, veers between explicit re-appropriation and aesthetic parallel. Among the former is Runa Islam’s three-screen installation Tuin, which deconstructs a 360-degree tracking shot during a pivotal encounter in Fassbinder’s 1974 film, Martha. Danish artist Jesper Just told LightBox he did not, in fact, have Fassbinder in mind when he created A Fine Romance (2004), but this trilogy of short 35mm films recalls Fassbinder with their mannerist staging of men in a mirror-surfaced, neon-bathed bordello, building melodramatic moments in non-narrative contexts.

Accompanying the exhibition is a 300-page catalog featuring materials from the Fassbinder archives, critical texts about the filmmaker and artists, appreciations by the artists, and hundreds of stills drawn from Fassbinder’s entire body of work — and no shortage of words from the filmmaker himself. In an excerpt from a 1978 interview included in the catalog, Fassbinder describes the rectangular frame, common among both still and film photography, as representing a higher truth than life.

“I think that the frame is like life,” he said. “Life, too, only provides certain opportunities. Film is like a square of life; it has the same boundaries. But I think that film is more honest, because it owns up to being a limited space. Life pretends to provide more opportunities. That’s why it’s a bigger lie.”

The Fassbinder NOW catalogue is available online.

Jon Dieringer is a filmmaker, independent curator and the editor and publisher of Screen Slate, a daily online resource for listings and commentary of New York City repertory film and independent media.

More Must-Reads from TIME

- Inside Elon Musk’s War on Washington

- Meet the 2025 Women of the Year

- The Harsh Truth About Disability Inclusion

- Why Do More Young Adults Have Cancer?

- Colman Domingo Leads With Radical Love

- How to Get Better at Doing Things Alone

- Cecily Strong on Goober the Clown

- Column: The Rise of America’s Broligarchy

Contact us at letters@time.com